Methdology Stuff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LS17.17022-Program-Web

ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO The CSO is assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body New Combination “Bean” Lorry No.341 commissioned 31st December 1925. 115 YEARS OF POWERING PROGRESS TOGETHER Since 1901, Shell has invested in large projects which have contributed to the prosperity of the Australian economy. We value our partnerships with communities, governments and industry. And celebrate our longstanding partnership with the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. shell.com.au Photograph courtesy of The University of Melbourne Archives 2008.0045.0601 SHA3106__CSO_245x172_V3.indd 1 20/09/2016 2:53 PM ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO Wednesday 17 May & Thursday 18 May, 2017 Llewellyn Hall, ANU 7.30pm Conductor Stanley Dodds Cello Umberto Clerici ----- HAYDN: Overture to L’isola disabitata (The Desert Island), Hob 28/9 8’ SCHUMANN: Cello Concerto in A minor, op. 129 25’ 1. Nicht zu schnell 2. Langsam 3. Sehr lebhaft INTERMISSION SCULTHORPE: String Sonata No. 3 (Jabiru Dreaming) 8’ 1 Deciso 2 Liberamente – Estatico BRAHMS: Symphony No. 3 in F major, op. 90 33’ 1. Allegro con brio 2. Andante 3. Poco allegretto 4. Allegro Please note: this program is correct at time of printing, however it is subject to change without notice. Umberto Clerici’s performance is supported by the Embassy of Italy in Canberra, Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Sydney and Schiavello enterprise Cover photo by Sarah Walker Sarah Cover photo by 17022 SEASON 2017 ActewAGL Llewellyn Series: Cello, Horn, Violin “Music -

A History of Music Education in New Zealand State Primary and Intermediate Schools 1878-1989

CHRISTCHURCH COLLEGE OF EDUCATION LIBRARY A HISTORY OF MUSIC EDUCATION IN NEW ZEALAND STATE PRIMARY AND INTERMEDIATE SCHOOLS 1878-1989 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Susan P. Braatvedt B.A. (Natal), Dip.Arts (Auckland), B.A.Rons (Canterbury) VOLUME II University of Canterbury 2002 Chapter Five 1950-1968 266 The growth ofschool music Chapter Five 1950 -1968 The growth of school music "music is fmnly established as an integral part of the school curriculum."l 5.1 Introduction This 18-year period was dominated by the National Party except for one term when Labour was voted back into office from 1958? When the National Party took office in December 1949, they inherited an educational system in which school music had not been particularly well served. Robert Chapman comments: The underlying changes in the golden 1960s were social rather than political, technological rather than legislative, individual rather than public ....The tertiary education boom, television, and the contraceptive pill were transforming family and personal relationships as well as the method by which politics were perceived. Government expenditure underwrote the surging development of health and education ... 3 In chapter one section 1.2 it was pointed out that the influence of English music education endured for many years. It is in this period that we begin to see a development of a more innovative approach which was more eclectic in its character. 1 AE. Campbell, Director-General of Education, AJHR. E-1, 1966, p.17. 2 R Chapman, 'From Labour to National,' The Oxford History ofNew Zealand, W.H. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

Symphonic Dances

ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEASON 2019 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Fri 16, 8pm Sat 17, 6.30pm PRESENTING PARTNER Adelaide Town Hall 2 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Dalia Stasevska Conductor Fri 16, 8pm Louis Lortie Piano Sat 17, 6.30pm Adelaide Town Hall John Adams The Chairman Dances: Foxtrot for Orchestra Ravel Piano Concerto in G Allegramente Adagio assai Presto Louis Lortie Piano Interval Rachmaninov Symphonic Dances, Op.45 Non allegro Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) Lento assai - Allegro vivace Duration Listen Later This concert runs for approximately 1 hour This concert will be recorded for delayed and 50 minutes, including 20 minute interval. broadcast on ABC Classic. You can hear it again at 2pm, 25 Aug, and at 11am, 9 Nov. Classical Conversation One hour prior to Master Series concerts in the Meeting Hall. Join ASO Principal Cello Simon Cobcroft and ASO Double Bassist Belinda Kendall-Smith as they connect the musical worlds of John Adams, Ravel and Rachmaninov. The ASO acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past, present and future. 3 Vincent Ciccarello Managing Director Good evening and welcome to tonight’s Notwithstanding our concertmaster, concert which marks the ASO debut women are significantly underrepresented of Finnish-Ukrainian conductor, in leadership positions in the orchestra. Dalia Stasevska. Things may be changing but there is still much work to do. Ms Stasevska is one of a growing number of young women conductors Girls and women are finally able to who are making a huge impression consider a career as a professional on the international orchestra scene. -

October 1936) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 10-1-1936 Volume 54, Number 10 (October 1936) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 54, Number 10 (October 1936)." , (1936). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/849 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE zJxtusic ^Magazine ©ctefoer 1936 Price 25 Cents ENSEMBLES MAKE INTERESTING RECITAL NUVELTIES PIANO Pianos as are Available The Players May Double-Up on These Numbers Employing as Many By Geo. L. Spaulding Curtis Institute of Music Price. 40 cents DR. JOSEF HOFMANN, Director Faculty for the School Year 1936-1937 Piano Voice JOSEF HOFMANN, Mus. D. EMILIO de GOGORZA DAVID SAPERTON HARRIET van EMDEN ISABELLE VENGEROVA Violin Viola EFREM ZIMBALIST LEA LUBOSHUTZ Dr. LOUIS BAILLY ALEXANDER HILSBERG MAX ARONOFF RUVIN HEIFETZ Harp Other Numbers for Four Performers at One Piamo Violincello CARLOS SALZEDO Price Cat. No. Title and Composer Cat. No. Title and Composer 26485 Song of the Pinas—Mildred Adair FELIX SALMOND Accompanying and $0.50 26497 Airy Fairies—Geo. -

Australian Composers & Sourcing Music

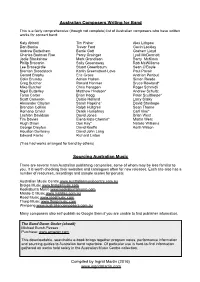

Australian Composers Writing for Band This is a fairly comprehensive (though not complete) list of Australian composers who have written works for concert band: Katy Abbott Tim Fisher Alex Lithgow Don Banks Trevor Ford Gavin Lockley Andrew Batterham Barrie Gott Graham Lloyd Charles Bodman Rae Percy Grainger Lyall McDermott Jodie Blackshaw Mark Grandison Barry McKimm Philip Bracanin Sally Greenaway Rob McWilliams Lee Bracegirdle Stuart Greenbaum Sean O’Boyle Brenton Broadstock Karlin Greenstreet-Love Paul Pavoir Gerard Brophy Eric Gross Andrian Pertout Colin Brumby Adrian Hallam Simon Reade Greg Butcher Ronald Hanmer Bruce Rowland* Mike Butcher Chris Henzgen Roger Schmidli Nigel Butterley Matthew Hindson* Andrew Schultz Taran Carter Brian Hogg Peter Sculthorpe* Scott Cameron Dulcie Holland Larry Sitsky Alexander Clayton Sarah Hopkins* David Stanhope Brendan Collins Ralph Hultgren Sean Thorne Romano Crivici Derek Humphrey Carl Vine* Lachlan Davidson David Jones Brian West Tim Davies Elena Kats-Chernin* Martin West Hugh Dixon Don Kay* Natalie Williams George Dreyfus David Keeffe Keith Wilson Houston Dunleavy David John Lang Edward Fairlie Richard Linton (*has had works arranged for band by others) Sourcing Australian Music There are several main Australian publishing companies, some of whom may be less familiar to you. It is worth checking their websites and catalogues often for new releases. Each site also has a number of resources, recordings and sample scores for perusal. Australian Music Centre www.australianmusiccentre.com.au Brolga Music www.brolgamusic.com Kookaburra Music www.kookaburramusic.com Middle C Music www.middlec.com.au Reed Music www.reedmusic.com Thorp Music www.thorpmusic.com Wirripang www.australiancomposers.com.au Many composers also self-publish so Google them if you are unable to find publisher information. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

ISME History Summary (English): Toward a Global Community: the History of the International Society for Music Education 1953-2003 by Marie Mccarthy

Toward a Global Community: The International Society for Music Eduction 1953-2003 by Marie McCarthy Celebrating 50 years 1953–2003 ISME History Summary (English): Toward a Global Community: The History of the International Society for Music Education 1953-2003 by Marie McCarthy Greetings On July 9, 2003, ISME celebrates 50 years since it was established in Brussels, Belgium, in 1953. It has been my privilege and honour to have been associated with ISME since its formation. A history such as this puts the work and achievements of the Society into perspective; it gives us an opportunity for reflection, and to acknowledge the contributions of so many loyal members and major organisations which have been players in the development of the Society. There could be no better choice of author to write this history than Marie McCarthy, who in its preparation has shown a deep interest and dedication to the task. This history is one of the many exciting projects celebrating the Golden Jubilee of ISME, and I commend it to you, the reader. Share it with colleagues and pass on the torch to your students who are the future of the Society. Encourage them to continue to work to uphold the fine aims and ideals of ISME. Frank Callaway Honorary President, ISME February 2003 Preface and Acknowledgments The idea of writing this history originated in the mind of then Honorary President, Sir Frank Callaway, to whom this book is dedicated. He approached me with the idea at the biennial conference in Amsterdam in 1996, and I am indebted to him for constant support and guidance right up to the end of his life. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

An Introductory Survey on the Development of Australian Art Song with a Catalog and Bibliography of Selected Works from the 19Th Through 21St Centuries

AN INTRODUCTORY SURVEY ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUSTRALIAN ART SONG WITH A CATALOG AND BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS FROM THE 19TH THROUGH 21ST CENTURIES BY JOHN C. HOWELL Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. __________________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Research Director and Chairperson ________________________________________ Gary Arvin ________________________________________ Costanza Cuccaro ________________________________________ Brent Gault ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to so many wonderful individuals for their encouragement and direction throughout the course of this project. The support and generosity I have received along the way is truly overwhelming. It is with my sincerest gratitude that I extend my thanks to my friends and colleagues in Australia and America. The Australian-American Fulbright Commission in Canberra, ACT, Australia, gave me the means for which I could undertake research, and my appreciation goes to the staff, specifically Lyndell Wilson, Program Manager 2005-2013, and Mark Darby, Executive Director 2000-2009. The staff at the Sydney Conservatorium, University of Sydney, welcomed me enthusiastically, and I am extremely grateful to Neil McEwan, Director of Choral Ensembles, and David Miller, Senior Lecturer and Chair of Piano Accompaniment Unit, for your selfless time, valuable insight, and encouragement. It was a privilege to make music together, and you showed me how to be a true Aussie. The staff at the Australian Music Centre, specifically Judith Foster and John Davis, graciously let me set up camp in their library, and I am extremely thankful for their kindness and assistance throughout the years. -

14Th Annual Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2012

australian societa y fo r s music educationm e What Would Peggy Do? i ncorporated 14th Annual Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2012 Michael Kieran Harvey The New Music Network established the Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address in 1999 in honour of one of Australia’s great international composers. It is an annual forum for ideas relating to the creation and performance of Australian music. In the spirit of the great Australian composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks, an outstanding advocate of Australian music delivers the address each year, challenging the status quo and raising issues of importance in new music. In 2012, Michael Kieran Harvey was guest speaker presenting his Address entitled What Would Peggy Do? at the Sydney Conservatorium on 22 October and BMW Edge Fed Square in Melbourne on 2 November 2012. The transcripts are reproduced with permission by Michael Kieran Harvey and the New Music Network. http://www.newmusicnetwork.com.au/index.html Australian Journal of Music Education 2012:2,59-70 Just in case some of you are wondering about I did read an absolutely awe-inspiring Peggy what to expect from the original blurb for this Glanville-Hicks Address by Jon Rose however, address: the pie-graphs didn’t quite work out, and and I guess my views are known to the address powerpoint is so boring, don’t you agree? organisers, so, therefore, I will proceed, certain For reasons of a rare dysfunctional condition in the knowledge that I will offend many and I have called (quote) “industry allergy”, and for encourage, I hope, a valuable few. -

The 11Th WIPAC Piano Competition!

Established 2001 ________________________________________________________ Dedicated to creating a Renaissance of interest in the Art of Piano Performance ♫ Making music flourish in our communities ♫ Promoting international friendship and cultural understanding through the art of classical piano music ♫♫♫ 3862 Farrcroft Drive, Fairfax, VA 22030 USA E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.wipac.org (703) 728-7766 …………………..…………... A Message from the Chair Welcome to The Festival of Music 2013 & The 11th Washington International Piano Artists Competition Washington International Piano Arts Council (WIPAC) continues to present this celebration of music in cooperation with The George Washington Music Department, The Kosciuszko Foundation and the Embassies of Bulgaria and Portugal. The path to success in this competition was made easier and manageable by all the special people I met who supported us along the way. May I begin with a special thanks to a very special friend of WIPAC, Her Excellency Elena Poptodorova, Ambassador of Bulgaria, who has been a bright light that shines on that path. Her generosity had no bounds, always welcoming and standing ready to open the door to help us. The Embassy of Bulgaria hosts the Final Round of this year’s competition, even in her unscheduled absence. To all the pianists who came from three continents, my admiration and deep appreciation for your valor, strength, tenacity and hard work, preparing your programs and practicing many hours at the same time as maintaining a busy life of career and family! A toast! John and I consider ourselves very fortunate to be surrounded by dedicated board members and friends who continue to keep our torch burning so that we may give the pianists a place in the sky where they can showcase their amazing talents.