The Practice of Knowledge Exchange April

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Construcción Histórica En La Cinematografía Norteamericana

Tesis doctoral Luis Laborda Oribes La construcción histórica en la cinematografía norteamericana Dirigida por Dr. Javier Antón Pelayo Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Historia Moderna Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona 2007 La historia en la cinematografía norteamericana Luis Laborda Oribes Agradecimientos Transcurridos ya casi seis años desde que inicié esta aventura de conocimiento que ha supuesto el programa de doctorado en Humanidades, debo agradecer a todos aquellos que, en tan tortuoso y apasionante camino, me han acompañado con la mirada serena y una palabra de ánimo siempre que la situación la requiriera. En el ámbito estrictamente universitario, di mis primeros pasos hacia el trabajo de investigación que hoy les presento en la Universidad Pompeu Fabra, donde cursé, entre las calles Balmes y Ramon Trias Fargas, la licenciatura en Humanidades. El hado o mi más discreta voluntad quisieron que iniciara los cursos de doctorado en la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, donde hoy concluyo felizmente un camino repleto de encuentros. Entre la gente que he encontrado están aquellos que apenas cruzaron un amable saludo conmigo y aquellos otros que hicieron un alto en su camino y conversaron, apaciblemente, con el modesto autor de estas líneas. A todos ellos les agradezco cuanto me ofrecieron y confío en haber podido ofrecerles yo, a mi vez, algo más que hueros e intrascendentes vocablos o, como escribiera el gran bardo inglés, palabras, palabras, palabras,... Entre aquellos que me ayudaron a hacer camino se encuentra en lugar destacado el profesor Javier Antón Pelayo que siempre me atendió y escuchó serenamente mis propuestas, por muy extrañas que resultaran. -

DVD Und Blu-Ray

kultur- und medienzentrum altes rathaus lü bbecke Neuerwerbungen DVD und Blu-ray Mediothek Lübbecke Juli 2016 – Dezember 2016 Mediothek Lübbecke, Am Markt 3, 32312 Lübbecke, Tel.: (05741) 276-401 Diese Liste ist als pdf-Datei unter: www.luebbecke.de/mediothek hinterlegt . 1 Mediothek Lübbecke Am Markt 3, 32312 Lübbecke Telefon: (0 57 41) 276-401 [email protected] Öffnungszeiten Montag: geschlossen Dienstag: 11:00 18:30 Uhr Mittwoch: 13:00 – 18:30 Uhr Donnerstag: 13:00 – 18:30 Uhr Freitag: 11:00 – 18:30 Uhr Samstag: 10:00 – 13:00 Uhr 2 DVD + Blu-ray A Royal Night Out - 2 Prinzessinnen. 1 Nacht. / Regie: Julian Jarrold. Drehb.: Trevor De Silva ... Kamera: Christophe Beaucarne. Musik: Paul Englishby. Darst.: Sarah Gadon ; Bel Powley ; Jack Reynor ... - Grünwald : Concorde Home Entertainment , 2016. - 1 DVD (ca. 94 Min.)FSK: ab 6. - Orig.: Großbritannien, 2015. - Sprache: Deutsch, Englisch Nach der bedingungslosen Kapitulation der deutschen Wehrmacht am 8. Mai 1945 wollen die beiden Töchter des britischen Königs an den Siegesfeiern teilnehmen. Als die Prinzessinnen Elizabeth und Margaret ihren Aufpassern entwischen und getrennt werden, beginnt eine Odyssee durch die Londoner Nacht, bei der Elizabeth zarte Bande mit einem jungen Soldaten knüpft. Furiose, einfallsreiche Screwball-Komödie, die auf höchst amüsante Weise ein „Was wäre wenn“-Szenario mit der britischen Königsfamilie entfaltet. Vor allem dank der fulminanten Hauptdarstellerin verbinden sich mit bemerkenswerter Leichtigkeit märchenhafte und realistische Elemente. - Ab 14. (Filmdienst) Blu-ray A war / Filmregisseur: Tobias Lindholm ; Drehbuchautor: Tobias Lindholm ; Bildregisseur: Magnus Nordenhof Jønck ; Musikalischer Leiter: Sune Rose Wagner ; Schauspieler: Pilou Asbæk, Tuva Novotny, Dar Salim [und andere] . - Berlin : Studiocanal GmbH, 2016. -

Tom Kerwick Key Grip

Tom Kerwick Key Grip ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 122 Stethem Dr. Centereach, NY 11720 516-662-7655 E-mail: [email protected] Qualifications: 30 years experience as grip on motion pictures, Episodic TV, and commercials. Member of Local 52 IATSE Work History: Criminal Justice (2012) Key Grip Director: Steven Zaillian Director of Photography: Robert Elswit Gotham (2012) Key Grip Director: Francis Lawrence Director of Photography: Jo Willems The Avengers (2011) Key Grip NY Director: Joss Whedon Director of Photography: Seamus McGarvey Lola Versus (2011) Key Grip Director: Daryl Wein Director of Photography: Jakob Ihre Being Flynn (2011) Key Grip Director: Paul Weitz Director of Photography: Declan Quinn We need To talk about Kevin (2010) Key Grip Director: Lynne Ramsay Director of Photography: Seamus McGarvey The Beautiful Life - TV Series(2009) Key Grip Directors: various Director of Photography: Craig DiBona Twelve (2009) Key Grip Director: Joel Schummacher Director of Photography: Steve Fierberg Everyday (2009) Key Grip Director: Richard Levine Director of Photography: Nancy Schreiber Private Lives of Pippa Lee (2008) Key Grip Director: Rebecca Miller Director of Photography: Declan Quinn Rock On (2008) Key Grip NY Director: Todd Graff Director of Photography: Eric Steelberg For One More Day (2007) Key Grip Director: Lloyd Kramer Director of Photography: Tami Reiker Babylon Fields- TV (2007) Key Grip Director: Michael Cuesta Director of Photography: Romeo Tirone The Bronx is -

Filmy Z Napisami Dla Osób Niesłyszących I Niedosłyszących Zestawienie Bibliograficne Ce Cbiorrw Edagogiicnej Biblioteki Wojewrdckiej W Bielsku-Białej

Filmy z napisami dla osób niesłyszących i niedosłyszących Zestawienie bibliograficne ce cbiorrw edagogiicnej Biblioteki Wojewrdckiej w Bielsku-Białej Napisy w języku polskim: Filmy fabularne: 1. 1920 Bitwa warscawska [Film DVD] / reż. Jercy Hofman ; sien. Jarosław Sokrł, Jercy Hofman ; muc. Krcesimir Dębski ; cdj. Sławomir Idciak ; obsada: Daniel Olbryihski, Natasca Urbańska, Borys Scyi [et al.]. - Warscawa : Edipresse olska, 2012. DVD 4105 2. Barany [Film DVD] : islandcka opowieść / sien. i reż. Grímur Hákonarson ; cdj. Sturla Brandth Grøvlen ; muc. Atli Örvarsson ; obsada: Sigurður Sigurjrnsson, Therdrr Júliusson, Charlote Bøving [et al.]. - Warscawa : Gutek Film, [2016]. DVD 6131 3. Belfer [Film DVD] / reż. Łukasc alkowski ; sien. Jakub Żulicyk, Monika owalisc ; cdj. Marian rokop ; muc. Atanas Valkov ; obsada: Maiiej Stuhr, Magdalena Cieleika, Grcegorc Damięiki [et al.]. - [Warscawa] : ITI Neovision S.A., iop. 2017. DVD 6486 4. Belfer. Secon 2 [Film DVD] / reż. Krcysctof Łukascewiic, Maiiej Boihniak ; sien. Jakub Żulicyk [et al.] ; cdj. Miihał Soboiiński ; muc. Atanas Valkov ; obsada: Maiiej Stuhr, Miihalina Łabaic, Elica Ryiembel [et al.]. - Warscawa : ITI Neovision S.A., iop. 2017. DVD 6584 5. Bogowie [Film DVD] / reż. Łukasc alkowski ; sien. Krcysctof Rak ; cdj. iotr Soboiiński jr ; muc. Bartosc Chajdeiki ; obsada: Tomasc Kot, iotr Głowaiki, Scymon iotr Warscawski [et al.]. - Warscawa : Agora, [2015]. DVD 5189 6. Carte Blanihe [Film DVD] / sien. i reż. Jaiek Lusiński ; cdj. Witold łriiennik ; muc. aweł Luiewiic ; obsada: Andrcej Chyra, Urscula Grabowska, Arkadiusc Jakubik [et al.]. - Warscawa : Kino Świat, [2015]. DVD 5383 7. Chiihot losu [Film DVD] / reż. Maiiej Dejicer ; sien. Hanka Lemańska, Wojiieih Tomicyk ; cdj. Jarosław Żamojda ; muc. Bartosc Chajdeiki ; obsada: Marta Żmuda-Trcebiatowska, Mateusc Damięiki, Natalia Kleber [et al.]. -

ASC History Timeline 1919-2019

American Society of Cinematographers Historical Timeline DRAFT 8/31/2018 Compiled by David E. Williams February, 1913 — The Cinema Camera Club of New York and the Static Camera Club of America in Hollywood are organized. Each consists of cinematographers who shared ideas about advancing the art and craft of moviemaking. By 1916, the two organizations exchange membership reciprocity. They both disband in February of 1918, after five years of struggle. January 8, 1919 — The American Society of Cinematographers is chartered by the state of California. Founded by 15 members, it is dedicated to “advancing the art through artistry and technological progress … to help perpetuate what has become the most important medium the world has known.” Members of the ASC subsequently play a seminal role in virtually every technological advance that has affects the art of telling stories with moving images. June 20, 1920 — The first documented appearance of the “ASC” credential for a cinematographer in a theatrical film’s titles is the silent western Sand, produced by and starring William S. Hart and shot by Joe August, ASC. November 1, 1920 — The first issue of American Cinematographer magazine is published. Volume One, #1, consists of four pages and mostly reports news and assignments of ASC members. It is published twice monthly. 1922 — Guided by ASC members, Kodak introduced panchromatic film, which “sees” all of the colors of the rainbow, and recorded images’ subtly nuanced shades of gray, ranging from the darkest black to the purest white. The Headless Horseman is the first motion picture shot with the new negative. The cinematographer is Ned Van Buren, ASC. -

Creative Industries

Collaborative Production in the Creative Industries Editors: James Graham & Alessandro Gandini Collaborative Production in the Creative Industries Edited by James Graham and Alessandro Gandini University of Westminster Press www.uwestminsterpress.co.uk Published by University of Westminster Press 101 Cavendish Street London W1W 6XH www.uwestminsterpress.co.uk © The editors and several contributors 2017 First published 2017 Cover Design: Diane Jarvis Printed in the UK by Lightning Source Ltd. Print and digital versions typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd. ISBN (Paperback): 978-1-911534-28-0 ISBN (PDF): 978-1-911534-29-7 ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-911534-30-3 ISBN (Kindle): 978-1-911534-31-0 DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/book4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommer cial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This license allows for copying and distributing the work, provid ing author attribution is clearly stated, that you are not using the material for commercial purposes, and that modified versions are not distributed. The full text of this book has been peer-reviewed to ensure high academic standards. For full review policies, see: http://www.uwestminsterpress.co.uk/ site/publish/ Suggested citation: Graham, J. and Gandini, A. 2017. Collaborative Production in the Creative Industries. London: University of Westminster Press. DOI: https://doi. org/10.16997/book4. License: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 To read the free, open access version of this book online, visit https://doi.org/10.16997/book4 or scan this QR code with your mobile device: Competing interests The editor and contributors declare that they have no competing interests in publishing this book Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. -

British Society of Cinematographers

Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature Film 2020 Erik Messerschmidt ASC Mank (2020) Sean Bobbitt BSC Judas and the Black Messiah (2021) Joshua James Richards Nomadland (2020) Alwin Kuchler BSC The Mauritanian (2021) Dariusz Wolski ASC News of the World (2020) 2019 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC 1917 (2019) Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC The Irishman (2019) Lawrence Sher ASC Joker (2019) Jarin Blaschke The Lighthouse (2019) Robert Richardson ASC Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019) 2018 Alfonso Cuarón Roma (2018) Linus Sandgren ASC FSF First Man (2018) Lukasz Zal PSC Cold War(2018) Robbie Ryan BSC ISC The Favourite (2018) Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Bad Times at the El Royale (2018) 2017 Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Blade Runner 2049 (2017) Ben Davis BSC Three Billboards outside of Ebbing, Missouri (2017) Bruno Delbonnel ASC AFC Darkest Hour (2017) Dan Laustsen DFF The Shape of Water (2017) 2016 Seamus McGarvey ASC BSC Nocturnal Animals (2016) Bradford Young ASC Arrival (2016) Linus Sandgren FSF La La Land (2016) Greig Frasier ASC ACS Lion (2016) James Laxton Moonlight (2016) 2015 Ed Lachman ASC Carol (2015) Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC Sicario (2015) Emmanuel Lubezki ASC AMC The Revenant (2015) Janusz Kaminski Bridge of Spies (2015) John Seale ASC ACS Mad Max : Fury Road (2015) 2014 Dick Pope BSC Mr. Turner (2014) Rob Hardy BSC Ex Machina (2014) Emmanuel Lubezki AMC ASC Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014) Robert Yeoman ASC The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Lukasz Zal PSC & Ida (2013) Ryszard Lenczewski PSC 2013 Phedon Papamichael ASC -

Leica. Finally. Only from Band Pro Worldwide

Leica. Finally. Only from Band Pro worldwide. Band Pro Presents Leica Summilux-C™ Primes Extraordinary prime lenses that deliver future-proof optical performance on any resolution PL mount camera. US $7.00 Cine Gear Expo Booth # 70 SPRING–SUMMER 2010 SPRING–SUMMER Burbank 818 841 9655 • New York 212 227 8577 • Munich +49 89 94 54 84 90 • Tel Aviv 972 3 5621631 Display Until September 2010 Display WWW. BANDPRO. COM • WWW. BANDPRO. DE WWW.SOC.ORG CAMERA OPERATOR VOLUME 19, NUMBER 2 SPRING/SUMMER 2010 Why use a fully CGI image on the cover of Camera Operator magazine? Even if a shot like this is made in the computer, it certainly tells the reader what they are going to read about. Frankly, with a movie like this, I think many people forget that there were camera operators involved at all. With such great work, I’d hate for that to happen. —Jack Messitt, editor COURTESY OF WETA OF COURTESY Features The Dolly Grip Has My Back by Dan Gold SOC Proof that the dolly grip is a camera operator’s best 8 friend and lifesaver. Taming 3D Steadicam for Avatar Cover by David Emmerichs SOC Hazards and solutions for Steadicam with two cameras 14 on board. Crossing the Line Introducing a new series Camera operators try their hands at above the line 22 Jake Sully’s fi ghting jobs like directing. blue alien from Avatar, based on motion capture with actor Sam Truth Never Lies Worthington, by Sawyer Gunn courtesy of WETA Interview with Director Aiken Weiss and DP David J 24 Frederick about their award-winning movie. -

Elegies to Cinematography: the Digital Workflow, Digital Naturalism and Recent Best Cinematography Oscars Jamie Clarke Southampton Solent University

CHAPTER SEVEN Elegies to Cinematography: The Digital Workflow, Digital Naturalism and Recent Best Cinematography Oscars Jamie Clarke Southampton Solent University Introduction In 2013, the magazine Blouinartinfo.com interviewed Christopher Doyle, the firebrand cinematographer renowned for his lusciously visualised collaborations with Wong Kar Wai. Asked about the recent award of the best cinematography Oscar to Claudio Miranda’s work on Life of Pi (2012), Doyle’s response indicates that the idea of collegiate collaboration within the cinematographic community might have been overstated. Here is Doyle: Okay. I’m trying to work out how to say this most politely … I’m sure he’s a wonderful guy … but since 97 per cent of the film is not under his control, what the fuck are you talking about cinematography ... I think it’s a fucking insult to cinematography … The award is given to the technicians … it’s not to the cinematographer … If it were me … How to cite this book chapter: Clarke, J. 2017. Elegies to Cinematography: The Digital Workflow, Digital Naturalism and Recent Best Cinematography Oscars. In: Graham, J. and Gandini, A. (eds.). Collaborative Production in the Creative Industries. Pp. 105–123. London: University of Westminster Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/book4.g. License: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 106 Collaborative Production in the Creative Industries I wouldn’t even turn up. Because sorry, cinematography? Really? (Cited in Gaskin, 2013) Irrespective of the technicolor language, Doyle’s position appeals to a tradi- tional and romantic view of cinematography. This position views the look of film as conceived in the exclusive monogamy the cinematographer has histori- cally enjoyed on-set with the director during principal photography. -

Cinematic Evolution: What Can History Tell Us About the Future?

Cinematic Evolution: What Can History Tell Us About the Future? Author Maddock, Daniel Published 2015 Conference Title Conference Proceedings of CreateWorld 2015: A Digital Arts Conference Version Version of Record (VoR) Copyright Statement © 2015 Apple University Consortium (AUC). The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the conference's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/123547 Link to published version http://auc.edu.au/2015/01/cinematographic-evolution-what-can-history-tell-us-about-the- future/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Cinematic Evolution: What Can History Tell Us About the Future? Daniel Maddock Griffith Film School Griffith University, Brisbane d.maddock@griffith.edu.au Abstract mediums and draw on recent examples of current practice in mainstream Hollywood cinema to suggest how the definition Many commentators and proponents of the film industry of cinematography might be reframed. have called for a review of the cinematographic award ask- ing who is responsible for these images; the cinematograph- er or the visual effects artists. Theorist Jean Baudrillard said Virtual Image Creation: the Cinemato- cinema plagiarises itself, remakes its classics, retro-activates its own myths. So, what can the history of filmmaking tell us graphic Argument about the practice of visual effects? James Cameron’s ground breaking film Avatar was released Four of the previous five winners for Best Cinematography in to record audiences in December 2009. It was a film much a Feature Film at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and discussed by critics and the wider media while it broke box- Sciences Awards (2009-2013) have been films which have office records becoming the highest grossing film in history contained a large component of computer generated im- at the time and the first film to gross more than two billion agery (animation and/or visual effects). -

Australian Cinematographers Society V4.1 Now Releasedfirmware Cache Recording, Menu Updates & Much More!

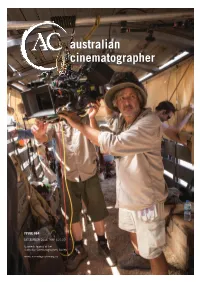

australian cinematographer ISSUE #64 DECEMBER 2014 RRP $10.00 Quarterly Journal of the Australian Cinematographers Society www.cinematographer.org.au V4.1 Now ReleasedFirmware Cache recording, menu updates & much more! The future, ahead of schedule Discover the stunning versatility of the new F Series Shooting in HD and beyond is now available to many more content creators with the launch of a new range of 4K products from Sony, the first and only company in the world to offer a complete 4K workflow from camera to display. PMW-F5 PMW-F55 The result of close consultation with top cinematographers, the new PMW-F5 and PMW-F55 CineAlta cameras truly embody everything a passionate filmmaker would want in a camera. A flexible system approach with a variety of recording formats, plus wide exposure latitude that delivers superior super-sampled images rich in detail with higher contrast and clarity. And with the PVM-X300 monitor, Sony has not only expanded the 4K world to cinema applications but also for live production, business and industrial applications. Shoot, record, master and deliver in HD, 2K or 4K. The stunning new CineAlta range from Sony makes it all possible. PVM-X300X300 For more information, please email us at [email protected] pro.sony.com.au MESM/SO140803/AC www.millertripods.com There’s one thing Production Directors can agree on... ;OL*PULSPULZL[ZUL^Z[HUKHYKZMVY*PULÅ\PKOLHKZ • Quick & easy to operate ‘all-in-one location’ rear 0SS\TPUH[LKWHU[PS[KYHNJV\U[LYIHSHUJLJVU[YVSZ mounted controls HUKI\IISLSL]LS • Side loading camera platform, 150mm travel with >PKL7H`SVHKYHUNLRN SIZ Arri type camera plate 7HU[PS[Å\PKKYHNWVZP[PVUZ • Drag control with ultra-soft starts and smooth stops 7VZP[PVUZVMJV\U[LYIHSHUJL ,HZ`[VÄ[4P[JOLSSIHZLHKHW[VY[VZ\P[4P[JOLSS ÅH[IHZL[YPWVKZ Contact your nearest Miller dealer today. -

La Lectora De Fontevraud

LA LECTORA DE FONTEVRAUD LA LECTORA DE FONTEVRAUD Derecho e Historia en el Cine. La Edad Media Enrique SAN MIGUEL PÉREZ Editorial Dykinson Todos los derechos reservados. Ni la totalidad ni parte de este libro, incluido el diseño de la cubierta, puede reproducirse o transmitirse por ningún procedimiento electrónico o mecánico. Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra solo puede ser realizada con la autorización de sus titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Diríjase a CEDRO (Centro Español de Derechos Reprográficos) si necesita fotocopiar o escanear algún fragmento de esta obra (www.conlicencia.com; 91 702 19 70 / 93 272 04 47) © Copyright Enrique San Miguel Pérez Editorial DYKINSON, S.L. Meléndez Valdés, 61 - 28015 Madrid Teléfono (+34) 91544 28 46 - (+34) 91544 28 69 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.dykinson.es http://www.dykinson.com Consejo editorial véase www.dykinson.com/quienessomos ISBN: 978-84-9031-838-6 Depósito Legal: M-34894-2013 Preimpresión: Besing Servicios Gráficos [email protected] cine.indd 6 10/12/2013 16:44:24 Para Lourdes San Miguel Gutiérrez, después de Chinon ÍNDICE Presentación: una lectora en Fontevraud ..................... 15 1. Civilización: escapar de la magia de los recuerdos .......................................................... 19 2. ¿Qué Edad Media?: adorar lo imposible ................ 25 3. Medievo del derecho: reconstruir el pasado tal como debió ser ................................................ 43 4. La acción política y de gobierno: sobre el rey ....... 55 5. Europa y Oriente: o hacia el horizonte, o hacia el poder ................................................................ 69 6. El nacimiento de la identidad: extender el amor a la virtud y la sabiduría .......................................