173 Chatham Island Rail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fulica Cornuta Bonaparte 1853 Nombre Común: Tagua Cornuda; Polla De Agua; Pato Negro; Gallina; Soca; Horned Coot (Inglés), Wari (Kunza)

FICHA DE ANTECEDENTES DE ESPECIE Id especie: Nombre Científico: Fulica cornuta Bonaparte 1853 Nombre Común: tagua cornuda; polla de agua; pato negro; gallina; soca; Horned Coot (inglés), Wari (kunza) Reino: Animalia Orden: Gruiformes Phyllum/Divis ión: Chordata Familia: Rallidae Clase: Aves Género: Fulica Sinonimia: Sin sinonimia Nota Taxonómica: Antecedentes Generales: ASPECTOS MORFOLÓGICOS: La tagua cornuda tiene el cuerpo rechoncho, de color uniformemente negruzco en ambos sexos, con la cabeza, cuello y hasta la espalda algo más oscura, y más gris apizarrada en la cara ventral del cuerpo. Los juveniles son en general más claros, sin negro en la cabeza y presentan una mancha blanca en el mentón y garganta. En el adulto el pico es fuerte y de color amarillo anaranjado, con una mancha negra en el culmen; en tanto que en los juveniles, el pico es negro verdoso con ligero tinte café. Las piernas en adultos y juveniles son de color verdoso, tirando al café con tinte gris oscuro a nivel de las articulaciones. Los dedos lobulados y provistos de poderosas uñas, son de gran tamaño, llegando a medir entre 20 y 30 cm de largo el dedo mayor. Los pies de los machos son apreciablemente más grandes que las de las hembras (Goodall et al. 1964, Araya et al. 1998, Martínez & González 2004, Jaramillo 2005). En los polluelos las piernas son negras, pero el pico es rosado con punta negra y amarilla y el cuerpo cubierto de un plumón fino y completamente negro, a excepción de una pequeña zona de plumillas blanquecinas en el mentón. El iris en el polluelo y en el ave juvenil es de color café, cambiando progresivamente mientras avanza a la adultez, hasta adquirir el característico color café anaranjado (Goodall et al. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

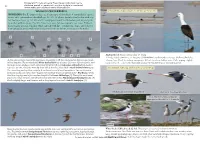

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

A Classification of the Rallidae

A CLASSIFICATION OF THE RALLIDAE STARRY L. OLSON HE family Rallidae, containing over 150 living or recently extinct species T and having one of the widest distributions of any family of terrestrial vertebrates, has, in proportion to its size and interest, received less study than perhaps any other major group of birds. The only two attempts at a classifi- cation of all of the recent rallid genera are those of Sharpe (1894) and Peters (1934). Although each of these lists has some merit, neither is satisfactory in reflecting relationships between the genera and both often separate closely related groups. In the past, no attempt has been made to identify the more primitive members of the Rallidae or to illuminate evolutionary trends in the family. Lists almost invariably begin with the genus Rdus which is actually one of the most specialized genera of the family and does not represent an ancestral or primitive stock. One of the difficulties of rallid taxonomy arises from the relative homo- geneity of the family, rails for the most part being rather generalized birds with few groups having morphological modifications that clearly define them. As a consequence, particularly well-marked genera have been elevated to subfamily rank on the basis of characters that in more diverse families would not be considered as significant. Another weakness of former classifications of the family arose from what Mayr (194933) referred to as the “instability of the morphology of rails.” This “instability of morphology,” while seeming to belie what I have just said about homogeneity, refers only to the characteristics associated with flightlessness-a condition that appears with great regularity in island rails and which has evolved many times. -

Nesting Habitat and Breeding Success of Fulica Atra in Tree Wetlands in Fez's Region, Central Morocco

J Anim Behav Biometeorol (2020) 8:282-287 ISSN 2318-1265 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Nesting habitat and breeding success of Fulica atra in tree wetlands in Fez’s region, central Morocco Wafae Squalli ▪ Ismail Mansouri ▪ Mohamed Dakki ▪ Fatima Fadil W Squalli (Corresponding author) ▪ I Mansouri ▪ F Fadil M Dakki Laboratory of Functional Ecology and Genie of Environment, Laboratory of Geo-biodiversity and Natural Heritage, Faculty of sciences and technology, USMBA, Fez, Morocco. Scientific Institute, Mohammed V University, Av. Ibn Battota, 10 BP 703, Rabat, Morocco. email: [email protected] Received: June 07, 2020 ▪ Accepted: July 15, 2020 ▪ Published Online: August 06, 2020 Abstract The current study was intended to investigate the in part, by interspecific (Fretwell and Lucas 1969; Jones 2001) breeding habitats and ecology of the Eurasian coot Fulica atra and intraspecific interactions (Morris 1989), climate contrast in Fez region Morocco. To achieve our goals, nests were (Martin 2001), and habitat degradation (Feary et al 2007). monitored in three wetlands Oued Al Jawahir river, Mahraz Understanding the dissimilarity between adaptive and and El Gaada dams. In addition, nesting vegetation and nest’s maladaptive animal use of habitat is needed for any dimensions were analysed to characterise the Eurasian coot conservation issue because animal use of inadequate habitat is nests. As results, 46 nests (74%) were found in Oued al counter to conservation drives (Case and Taper 2000). Jawahir, compared with 15 nests (24%) in Mahraz dam. In El Because species conservation worry often occurs in disturbed Gaada dam only 2 nests were built by the Eurasian coots. On habitats (Belaire et al 2014), patterns in habitat use in these the other hand, all nests were built on the riparian vegetation species may not always be revealing of the habitat conditions of the river and dams. -

Sex Determination of Adult Eurasian Coots (Fulica Atra) by Morphometric Measurements Author(S): Piotr Minias Source: Waterbirds, 38(2):191-194

Sex Determination of Adult Eurasian Coots (Fulica atra) by Morphometric Measurements Author(s): Piotr Minias Source: Waterbirds, 38(2):191-194. Published By: The Waterbird Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1675/063.038.0208 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1675/063.038.0208 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/ page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non- commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Sex Determination of Adult Eurasian Coots (Fulica atra) by Morphometric Measurements PIOTR MINIAS Department of Teacher Training and Biodiversity Studies, University of Lodz, Banacha 1/3, 90-237 Lodz, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—The aim of this study was to describe the size dimorphism in adult Eurasian Coots (Fulica atra). Ap- propriate discriminant functions to allow efficient sex determination on the basis of morphological measurements were developed. Breeding Eurasian Coots (n = 55) were captured from the urban population in central Poland. -

Supplementary Information

Supporting Information Balk et al. 10.1073/pnas.0902903106 Movie S1. A paralyzed herring gull (Larus argentatus). This movie shows a specimen from the County of So¨ dermanland (region G in Fig. 1). Both wings are equally paralyzed and the beak has no strength, whereas mobility and control of the head still remain. In this work we demonstrate that the probability to remedy an individual in this condition by thiamine treatment is very high. The movie is taken in the field, but the specimen is placed on a black tablecloth in order to remove disturbing background and enhance contrast. Movie S1 (AVI) Other Supporting Information Files SI Appendix Balk et al. www.pnas.org/cgi/content/short/0902903106 1of1 Supporting Information Wild birds of declining European species are dying from a thiamine deficiency syndrome L. Balk*, P.-Å. Hägerroth, G. Åkerman, M. Hanson, U. Tjärnlund, T. Hansson, G. T. Hallgrimsson, Y. Zebühr, D. Broman, T. Mörner, H. Sundberg *Corresponding author: [email protected] Contents Pages M & M Materials and Methods. 2–10 Text S1 Additional bird species affected by the paralytic disease. 11 Text S2 Additional results for eggs. 12–13 Text S3 Results for liver body index (LBI) in pulli. 14–15 Text S4 Breeding output and population estimates. 16–18 Text S5 Elaborated discussion of important aspects. 19–27 Acknowl. Further acknowledgements. 28 Fig. S1 a–j The 83 locations where samples were collected. 29–30 Fig. S2 a–d Pigmentation changes in the iris of the herring gull (Larus argentatus). 31 Fig. S3 Liver α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH) in common black-headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus). -

Diet of Non-Breeding Wildfowl Anatidae and Coot Fulica Atra on the Perthois Gravel Pits, Northeast France

68 Diet of non-breeding wildfowl Anatidae and Coot Fulica atra on the Perthois gravel pits, northeast France JEAN-BAPTISTE MOURONVAL1, MATTHIEU GUILLEMAIN1, AURELIEN CANNY2 & FREDERIK POIRIER3 1Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage, CNERA Avifaune Migratrice, La Tour du Valat, Le Sambuc, 13200 Arles, France. Email: [email protected] 2Champagne Ardenne Nature Environnement, Musée du Pays du Der, 51290 Sainte Marie du Lac, France. 3Syndicat Mixte d’Aménagement Touristique du Lac du Der, Maison du Lac, 51290 Giffaumont Champaubert, France. Abstract Gravel pits are important habitats for wintering waterbirds, yet food selection by wildfowl wintering at these wetlands has seldom been studied. Here we describe the diet of eight dabbling and diving duck species, and also of Coot Fulica atra, at the Perthois gravel pits in northeast France. The pits form part of a broader Ramsar area and are in themselves of national importance for several Anatidae. From 343 guts collected, the gross diet of the nine bird species corresponded to that reported in the literature for these waterbirds on other types of inland wetlands, though Pochard Ayhtya ferina were almost exclusively granivorous here whereas earlier studies found that they fed more on invertebrates. All nine bird species ingested seeds, often in abundance, though in addition to Pochard only Teal Anas crecca and Mallard A. platyrhynchos could be considered as being true granivores. Two species (Spiny Naiad Naïas marina and Small Pondweed Potamogeton pusillus) were consistently among the most consumed seeds in eight out of nine bird species. The importance of these plant species may be typical to gravel pit in this study area. -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í. -

Wildlife Enhancement Plan 2014–2019 Aims to Support Increased Biodiversity and the Conservation of Native Fauna and Fauna Habitat Within the Local Environment

Wildlife Enhancement Plan 2014 – 2019 www.subiaco.wa.gov.au Goal statement The Wildlife Enhancement Plan 2014–2019 aims to support increased biodiversity and the conservation of native fauna and fauna habitat within the local environment. Acknowledgements The city would like to thank Danielle Bowler from the City of Joondalup, Tamara Kabat from Bird Life Australia, Mathew Swan from the Department of Parks and Wildlife and Jake Tanner from the City of Fremantle for assisting with the development of this plan. The City of Subiaco is committed to protecting the global environment through local action. By printing this publication on Australian made 100 per cent recycled paper, the city aims to conserve the resources of the city. The document is available via the Internet at www.subiaco.wa.gov.au TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents Executive summary 4 Key definitions 5 Introduction 6 Wildlife conservation and enhancement 7 Parks, reserves and street trees 7 Wetlands 7 Greenways and remnant bushland areas 8 Aboriginal cultural significance 8 Community education 8 Management of identified risks 10 Climate change 10 Feral animals 10 Domestic animals 10 Plant pathogens 10 Resources and useful links 11 References 12 Appendix A: Fauna list 13 Photo courtesy of Margaret Owen CITY OF SUBIACO 2014 –2019 WILDLIFE ENHANCEMENT PLAN | 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Executive summary The Wildlife Enhancement Plan 2014–2019 aims to support increased biodiversity and the conservation of native fauna and fauna habitat within the city’s local environment. The plan includes actions to enhance wildlife conservation, as well as provide education and participation opportunities for the community. -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

Diving Behaviour of the Australian Coot in a New Zealand Lake

By BRIGITTE J. BAKKER and R.A. FORDHAM ABSTRACT In a 1-day study of the Australian Coot (Fulica atra australis), the duration of dives increased with increasing depth, although the frequency of diving remained relatively constant. Duration and frequency of dives at given depths appeared not to vary with age. However, aggressive adults often drove young birds into deeper water. The duration of dives changed with the time of day, the birds preferring to dive in direct sunlight. INTRODUCTION Foraging diving birds have limited capacity to find food under water. The effort put into foraging can be assessed from the frequency and duration of their dives in both carnivorous and vegetarian birds. In these two groups diving is likely to differ because carnivorous birds dive to chase and catch live prey, which are often mobile, whereas the food of vegetarian birds is usually fixed at a certain depth or location. Most studies of diving behaviour have been with carnivorous birds (Stonehouse 1967, Piatt & Nettleship 1985, Cooper 1986, Wanless et al. 1988, Wilson & Wilson 1988, Strong & Bissonette 1989), and relatively little attention has been paid to predominantly herbivorous birds, such as rails (Dewar 1924, Batulis & Bongiorno 1972). Coots, which are energetic diving rails with regular feeding bouts, forage mostly on benthic plant material and are therefore good subjects for studying diving behaviour in a vegetarian bird. Diving times and pauses in the American Coot (Fulica americana) were measured in relation to water depth by Batulis & Bongiorno (1972). They found that differences in water depth affected diving times and pauses although divelpause ratios remained constant.