The New Mon State Party (NMSP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mon Affairs Union Representative: Nai Bee Htaw Monzel

Mon Affairs Union Representative: Nai Bee Htaw Monzel Mr. Chairman or Madame Chairperson I would like to thank you for giving me the opportunity to participate in the Forum. I am representative from the Mon Affairs Union. The Mon Affairs Union is the largest Mon political and social organization in Mon State. It was founded by Mon organizations both inside and outside Burma in 2008. Our main objective to restore self-determination rights for Mon people in Burma. Mon people is an ethnic group and live in lower Burma and central Thailand. They lost their sovereign kingdom, Hongsawatoi in 1757. Since then, they have never regained their self- determination rights. Due to lack of self-determination rights, Mon people are barred from decision making processes on social, political and economic policies. Mon State has rich natural resources. Since the Mon do not have self-determination rights, the Mon people don’t have rights to make decision on using these resources. Mon State has been ruled by Burmese military for many years. Burmese military government extracts these resources and sells to neighboring countries such as China and Thailand. For example, the government sold billions of dollars of natural gas from Mon areas to Thailand. Instead of investing the income earned from natural gas in Mon areas, the government bought billion dollars of arms from China and Russia to oppress Mon people. Due Burmese military occupation in Mon areas, livelihoods of Mon people economic life have also been destroyed. Since 1995, Burmese military presence in Mon areas was substantially increased. Before 1995, Burma Army had 10 battalions in Mon State. -

Late Jomon Male and Female Genome Sequences from the Funadomari Site in Hokkaido, Japan

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 127(2), 83–108, 2019 Late Jomon male and female genome sequences from the Funadomari site in Hokkaido, Japan Hideaki KANZAWA-KIRIYAMA1*, Timothy A. JINAM2, Yosuke KAWAI3, Takehiro SATO4, Kazuyoshi HOSOMICHI4, Atsushi TAJIMA4, Noboru ADACHI5, Hirofumi MATSUMURA6, Kirill KRYUKOV7, Naruya SAITOU2, Ken-ichi SHINODA1 1Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tsukuba City, Ibaragi 305-0005, Japan 2Division of Population Genetics, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima City, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan 3Department of Human Genetics, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan 4Department of Bioinformatics and Genomics, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa City, Ishikawa 920-0934, Japan 5Department of Legal Medicine, Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Medicine and Engineering, University of Yamanashi, Chuo City, Yamanashi 409-3898, Japan 6Second Division of Physical Therapy, School of Health Sciences, Sapporo Medical University, Sapporo City, Hokkaido 060-0061, Japan 7Department of Molecular Life Science, School of Medicine, Tokai University, Isehara City, Kanagawa 259-1193, Japan Received 18 April 2018; accepted 15 April 2019 Abstract The Funadomari Jomon people were hunter-gatherers living on Rebun Island, Hokkaido, Japan c. 3500–3800 years ago. In this study, we determined the high-depth and low-depth nuclear ge- nome sequences from a Funadomari Jomon female (F23) and male (F5), respectively. We genotyped the nuclear DNA of F23 and determined the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class-I genotypes and the phenotypic traits. Moreover, a pathogenic mutation in the CPT1A gene was identified in both F23 and F5. The mutation provides metabolic advantages for consumption of a high-fat diet, and its allele fre- quency is more than 70% in Arctic populations, but is absent elsewhere. -

Rohingya Crisis: an Analysis Through a Theoretical Perspective

International Relations and Diplomacy, July 2020, Vol. 8, No. 07, 321-331 doi: 10.17265/2328-2134/2020.07.004 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Rohingya Crisis: An Analysis Through a Theoretical Perspective Sheila Rai, Preeti Sharma St. Xavier’s College, Jaipur, India The large scale exodus of Rohingyas to Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand as a consequence of relentless persecution by the Myanmar state has gained worldwide attention. UN Secretary General, Guterres called it “ethnic cleansing” and the “humanitarian situation as catastrophic”. This catastrophic situation can be traced back to the systemic and structural violence perpetrated by the state and the society wherein the Burmans and Buddhism are taken as the central rallying force of the narrative of the nation-state. This paper tries to analyze the Rohingya discourse situating it in the theoretical precepts of securitization, structural violence, and ethnic identity. The historical antecedents and particular circumstances and happenings were construed selectively and systematically to highlight the ethnic, racial, cultural, and linguistic identity of Rohingyas to exclude them from the “national imagination” of the state. This culture of pervasive prejudice prevailing in Myanmar finds manifestation in the legal provisions whereby certain peripheral minorities including Rohingyas have been denied basic civil and political rights. This legal-juridical disjunction to seal the historical ethnic divide has institutionalized and structuralized the inherent prejudice leveraging the religious-cultural hegemony. The newly instated democratic form of government, by its very virtue of the call of the majority, has also been contributed to reinforce this schism. The armed attacks by ARSA has provided the tangible spur to the already nuanced systemic violence in Myanmar and the Rohingyas are caught in a vicious cycle of politicization of ethnic identity, structural violence, and securitization. -

Using the National Historic Preservation Act to Protect Iconic Species

Hastings Environmental Law Journal Volume 12 Number 2 Spring 2006 Article 5 1-1-2006 The Cultural Significance of Wildlife: Using the National Historic Preservation Act to Protect Iconic Species Ingrid Brostrom Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_environmental_law_journal Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Ingrid Brostrom, The Cultural Significance of Wildlife: Using the National Historic Preservation Act to Protect Iconic Species, 12 Hastings West Northwest J. of Envtl. L. & Pol'y 147 (2006) Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_environmental_law_journal/vol12/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WEST NORTHWEST I have raised my children from the gifts from this sea. It’s our mission to pass this treasure to our offspring.1 - Oba San, 92-year-old Okinawan protestor The Cultural Significance of Wildlife: Using the National Historic I. Introduction Preservation Act to Protect Iconic Species Whether it be the emblematic bald eagle flying majestically overhead or the spawning salmon winding its way upstream, certain animals represent the By Ingrid Brostrom* cultural backbone of a people and bring meaning to the human world around them. A community can survive without these species but its unique cultural iden- tity may not. While every species has bio- logical and ecological value, some deserve extra protection for the signifi- cance they derive from the human popu- lations around them. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................ -

Collective Consciousness of Ethnic Groups in the Upper Central Region of Thailand

Collective Consciousness of Ethnic Groups in the Upper Central Region of Thailand Chawitra Tantimala, Chandrakasem Rajabhat University, Thailand The Asian Conference on Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences 2019 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This research aimed to study the memories of the past and the process of constructing collective consciousness of ethnicity in the upper central region of Thailand. The scope of the study has been included ethnic groups in 3 provinces: Lopburi, Chai-nat, and Singburi and 7 groups: Yuan, Mon, Phuan, Lao Vieng, Lao Khrang, Lao Ngaew, and Thai Beung. Qualitative methodology and ethnography approach were deployed on this study. Participant and non-participant observation and semi-structured interview for 7 leaders of each ethnic group were used to collect the data. According to the study, it has been found that these ethnic groups emigrated to Siam or Thailand currently in the late Ayutthaya period to the early Rattanakosin period. They aggregated and started to settle down along the major rivers in the upper central region of Thailand. They brought the traditional beliefs, values, and living style from the motherland; shared a sense of unified ethnicity in common, whereas they did not express to the other society, because once there was Thai-valued movement by the government. However, they continued to convey the wisdom of their ancestors to the younger generations through the stories from memory, way of life, rituals, plays and also the identity of each ethnic group’s fabric. While some groups blend well with the local Thai culture and became a contemporary cultural identity that has been remodeled from the profoundly varied nations. -

The Mon Language Editmj

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 The Mon language:recipient and donor between Burmese and Thai Jenny, Mathias Abstract: Mon is spoken in south Myanmar and parts of central and northern Thailand and has been in intense contact with its neighboring languages for many centuries. While Mon was the culturally and politically dominant language in the first millennium, its role was reduced to a local minority language first in Thailand, later in Myanmar. The different contact situations in which the Mon languagehas been between Thailand and Myanmar has led to numerous instances of language change. The influence has not been one-way, with Mon on the receiving end only, but Mon was also the source of restructuring in Burmese and Thai. The present paper attempts to trace some of the contact induced changes in the three languages involved. It is not always clear which language was the source of shared vocabulary and constructions, but in many cases linguistic and historical facts can be adduced to find answers. While Mon language use in Thailand is diminishing fast and Mon in this country is undergoing restructuring according to Thai patterns, in Myanmar Mon is actually still exerting influence on Burmese, albeit mostly on a local level in varieties spoken in Mon and Karen States. The contact between genetically and typologically very different languages as is the case here leads in many cases to linguistically interesting outcomes. Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-81044 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Jenny, Mathias (2013). -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

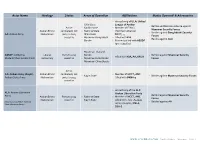

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Developing History Curricula to Support Multi-Ethnic Civil Society Among Burmese Refugees and Migrants

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Research Paper No. 139 Developing history curricula to support multi-ethnic civil society among Burmese refugees and migrants Rosalie Metro E-mail : [email protected] December 2006 Policy Development and Evaluation Service Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees P.O. Box 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates, as well as external researchers, to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction What children learn about history is widely recognized to influence their perceptions and behavior, yet little attention has been given to how to design history curricula for young people in conflict or post-conflict situations. This paper discusses possibilities for development of history curricula that can support multi-ethnic civil society among Burmese refugees, exiles, migrants, and ethnic nationals.1 The paper is adapted from the Master’s thesis I completed in 2003. The research presented here was conducted in February and March of 2003 in Chiang Mai, Mae Sot, Bangkok, and Mae Hong Son, Thailand. Using an action research methodology and an interview guide approach, I investigated history curricula currently in use in refugee camps along the Thai-Burma border, in Burmese-run schools in Thailand, and areas controlled by ethnic nationality groups inside Burma, including ceasefire areas. I then evaluated strategies for redesigning these curricula. -

Burma/Thailand

December 1994 Vol. 6, No. 14 BURMA/THAILAND THE MON: PERSECUTED IN BURMA, FORCED BACK FROM THAILAND I. Summary.......................................................................................................................................3 Recommendations................................................................................................................4 II. Human Rights Violations of the Mon by the Burmese Government.........................................5 Arrests and Extrajudicial Executions of Suspected Rebels .................................................5 Abuses Associated With Taxation.......................................................................................5 Forced Relocations...............................................................................................................6 Forced Labor........................................................................................................................8 III. Abuses of the Mon by the Thai Government .........................................................................11 The Attack on Halockhani Camp and the Thai Response .................................................12 The Treatment of Mon Migrant Workers by Thai Authorities ..........................................14 Thai Policy Towards Mon and Other Burmese Refugees .................................................16 IV. Conclusions.............................................................................................................................19 V. Recommendations....................................................................................................................21