Easier Rigs for Safer Cruising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appropriate Sailing Rigs for Artisanal Fishing Craft in Developing Nations

SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 2 July 1984 ORIGINAL : ENGLISH SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SIXTEENTH REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING ON FISHERIES (Noumea, New Caledonia, 13-17 August 1984) APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS by A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy LIBRARY SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION SPC/Fisheries 16/Background Paper 1 Page 1 APPROPRIATE SAILING RIGS FOR ARTISANAL FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING NATIONS A.J. Akester Director MacAlister Elliott and Partners, Ltd., U.K. and J.F. Fyson Fishery Industry Officer (Vessels) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy SYNOPSIS The plight of many subsistence and artisanal fisheries, caused by fuel costs and mechanisation problems, is described. The authors, through experience of practical sail development projects at beach level in developing nations, outline what can be achieved by the introduction of locally produced sailing rigs and discuss the choice and merits of some rig configurations. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. RISING FUEL COSTS AND THEIR EFFECT ON SMALL MECHANISED FISHING CRAFT IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 3. SOME SOLUTIONS TO THE PROBLEM 3.1 Improved engines and propelling devices 3.2 Rationalisation of Power Requirements According to Fishing Method 3.3 The Use of Sail 4. SAILING RIGS FOR SMALL FISHING CRAFT 4.1 Requirements of a Sailing Rig 4.2 Project Experience 5. DESCRIPTIONS OF RIGS USED IN DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 5.1 Gaff Rig 5.2 Sprit Rig 5.3 Lug Sails 5.3.1 Chinese type, fully battened lug sail 5.3.2 Dipping lug 5.3.3 Standing lug 5.4 Gunter Rig 5.5 Lateen Rig 6. -

2010 Year Book

2010 YEAR BOOK www.massbaysailing.org $5.00 HILL & LOWDEN, INC. YACHT SALES & BROKERAGE J boat dealer for Massachusetts and southern new hampshire Hill & Lowden, Inc. offers the full range of new J Boat performance sailing yachts. We also have numerous pre-owned brokerage listings, including quality cruising sailboats, racing sailboats, and a variety of powerboats ranging from runabouts to luxury cabin cruisers. Whether you are a sailor or power boater, we will help you find the boat of your dreams and/or expedite the sale of your current vessel. We look forward to working with you. HILL & LOWDEN, INC. IS CONTINUOUSLY SEEKING PRE-OWNED YACHT LISTINGS. GIVE US A CALL SO WE CAN DISCUSS THE SALE OF YOUR BOAT www.Hilllowden.com 6 Cliff Street, Marblehead, MA 01945 Phone: 781-631-3313 Fax: 781-631-3533 Table of Contents ______________________________________________________________________ INFORMATION Letter to Skippers ……………………………………………………. 1 2009 Offshore Racing Schedule ……………………………………………………. 2 2009 Officers and Executive Committee …………… ……………............... 3 2009 Mass Bay Sailing Delegates …………………………………………………. 4 Event Sponsoring Organizations ………………………………………................... 5 2009 Season Championship ………………………………………………………. 6 2009 Pursuit race Championship ……………………………………………………. 7 Salem Bay PHRF Grand Slam Series …………………………………………….. 8 PHRF Marblehead Qualifiers ……………………………………………………….. 9 2009 J105 Mass Bay Championship Series ………………………………………… 10 PHRF EVENTS Constitution YC Wednesday Evening Races ……………………………………….. 11 BYC Wednesday Evening -

Fitting the Unstayed Mast Rig To

ITTING THE UNSTAYED MAST RIG TO YOUR BOAT SOME POPULAR QUESTIONS ANSWERED: - . Will it suit any boat of any hull shape? - Yes, and will particularly aid shallow draft hulls of low ballast ratio as the flexibility of the mast reduces heeling in all conditions. 2. Can it be fitted to multihulls? - Yes, Trimaran installations are similar to monohulls. Catamarans can either have modified bridge decks to obtain sufficient bury of mast or fit a smaller mast in each hull. 3. Can I use my existing stayed rig mast?- No, with the exception of some solid timber Gaff rig masts. 4. Does the mast have to be keel stepped? - Preferably, but it can be fitted in a deck tabernacle. 5. Where is the mast stepped? - Approximately 2 to 4 feet forward of a stayed mast postion. 6. Does it have to be near a bulkhead? - No, as the load transmitted to the deck is not enormous. 7. What structural modifications will I have to make to my boat? - Probably increase the deck strength at the mast by adding:- - for GRP boats more layup of C.S. matt which will be hidden by the head lining under the deck. - for steel, alloy, ferrocement, timber boats, add a deck beam. The mast step only needs to be firmly secured to the keel and no extra reinforcement is necessary to be the boat's keel. - for sheeting to the pushpit, possibly, add a bracing strut across the existing tube, such as a sheet track. 8. How many sails and of what area should be used? - As a general rule:- For boats up to 30 ft., one sail is more ideal. -

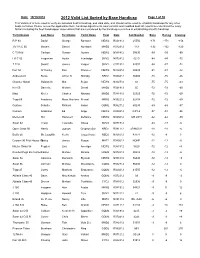

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Cape Cod Catboat

Cape Cod Catboat Instructions: Follow these instructions carefully and step by step. The rigging lines of the boat could tangle easily so do not undo the lines until instructed. 1. Unwrap the hull and stand. Place the hull into the stand with the hull facing forward to your right. Keep the starboard side of the boat facing you in order to follow the instructions and to compare with the diagrams. 2. Study brass eye “A” and the cleats on the boat. There are 7 cleats on this model but we will only be using 3-7. They each have a fixed position that corresponds to different rigging lines and sail sheets of the boat. See diagram (1). 3. Unwrap the packing of the mast; find brass eyes G1, G2, G3, G4, & G5 on the mast. The brass eyes must face towards the stern of the boat. Insert the mast into the mast step on the deck. 4. Unpack the sail. You may want to press the sail with an iron to get out any wrinkles. Find the headstay line on the front top portion of the mast. Attach the line to eye A on the bow. See diagram (1). 5. Put the gaff jaw at the end of gaff pole to brass eye M on the mast. Then find a pin at the end of the boom, insert the pin to a brass hole about 1 inch up the mast from the deck. Find a block with hook on the topping lift line. Attach the hook of the line to eye G1, then lead the line down the mast and through an eye at the bottom of the mast, starboard side, then fix the end of the line to cleat 4 on the cockpit bulkhead. -

Valid List by Design

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List by Design, Adjustments Page 1 of 31 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap. Design Last Name Yacht Name Record Date Base LP Adj Spin Rig Prop Rec Misc Race Cruise 1 D35 Schimenti Zefiro Toma R043012 36 -9 -3 24 42 12 Metre Gregory Valiant R071212 3 +6 9 9 12 Metre Mc Millen 111 Onawa R011512 33 -6 27 33 5.5 Carney Lyric R082912 156 u156 u165 8 Metre Palm Quest N071612 111 111 117 Aerodyne 38 D' Alessandro Alexis R053112 39 39 48 Akilaria Class 40 Davis Amhas R072312 -9 -9 -3 Akilaria Class 40 Dreese Toothface R041012 -9 -9 0 Alben 54 Ketch Wiseman Legacy V R070212 57 +6 +6 69 78 Alberg 35 Prefontaine Helios R042312 201 -3 198 210 Alberg 37 Mintz L' Amarre R061612 156 +6 +3 +6 171 186 Albin Cumulus Droste Cumulus 3 R030412 189 189 204 Albin Nimbus 42 Pomfret Anne R052212 99 99 111 Alden 42 S D S M Vieira Cadence R011312 120 +6 +6 132 144 Alden 44 Rice Pilgrim N053112 111 +9 +6 126 141 Alden 44 Weisman Nostos R011312 111 +9 +6 126 132 Alden 45 Davin Querence R071912 87 +9 +6 102 108 Alden 45" Seagoer Dunne Cygnet N040212 141 141 147 Alerion 26 Lurie Mischief R040612 225 U225 U231 Alerion Express 28 Brown Lumen Solare C082212 -

Chapter 7 Rigging the Sail

1 Chapter 7 (..of The Cambered Panel Junk Rig...) Rigging the sail. (..all those ropes!) Malena, 1.4t, 32sqm Johanna, 3.2t, 48sqm Broremann 0.20t, 10sqm Frk. Sørensen, 0.74t, 20m2 Ingeborg, 2.15t, 35sqm In this chapter, I will mainly tell how I have rigged my own sails, but may also show alternative ways of doing it. Actually, I think it is a good idea to read this chapter before one settles on a rig type. No doubt, this text will have to be updated several times, as I receive more feedback. I will frequently use links to other write-ups I have produced, to describe details. Since all of these sit on the same website, they will stay operational for as long as this chapter does. If you are a serious doer, I guess it makes sense to download these texts and store them. One never knows when a website might fold... Aluminium mast cap (5mm thick) Webbing type mast cap for 10sqm sail on Broremann. Preparing the mast for first stepping. With the mast in hand, one needs some way of attaching the halyard etc. to the mast top. My preferred way has been to make some sort of mast cap of steel or (better) aluminium. For smaller rigs, I have just made it out of webbing and fixed it to the mast with a couple of hose clamps. In the latter case, one should add a fez-type cap to it, to protect the webbing from the sun. All my mast tops have been of wood. -

Buy the Boat of Your Dreams from Campbell's!

Buy the boat of your dreams from Campbell’s! ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ www.campbellsyachtsales.com ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ CYS Featured Boats NEW LISTINGS 2002 Catalina 42 MK II “Two Cabin Pullman Model” 1986 Irwin 43 Center Console - $69,900 $126,500 This Irwin 43 has been privately owned. Two Cabin Pullman Catalina 42 that is completely loaded with • Yanmar Diesel with low hours gear. The owner has been meticulous in getting this boat exactly • Spacious aft cabin w/centerline berth the way he wanted it – with features that make it user friendly in and plenty of storage space. the sailing mode. Includes furling genoa, mack pack with Lazy Jack • Large forward berth , Two Heads System for the Main , Garhauer Rigid Boom Vang and Main Sheet • Shallow Draft, Heat/Air Conditioning, Traveler System, Flex 0 Fold Propeller and a Dodger/Bimini/ Radar, Autopilot, GPS, Plotter, Wind Connector over helm . The electronics include Garmin Touch Screen and more. Plotter, Wind, Depth, Speed, Autopilot at wheel. • Bow Thruster, Windlass, Bimini, Dodger, Dinghy Davits. Many upgrades and new equipment. Well Maintained. Great for a live aboard or cruising We are actively looking for new listings—contact P.J. about selling your boat. NEW LISTINGS * * * * * NEW PRICE REDUCTION * * * * * 1984 Marine Trader 50 Pilot House Motor Yacht $219,000 • Three Staterooms • Twin Ford Lehman 120hp Diesel Engines • Northern Lights Generator • Bow Thruster • Radar • GPS • Auto Pilot • Windlass • West Marine Inflatable with 8hp Engine 1986 Island Packet 27 “Angel” - $32,900 26,900 Features 18hp Yanmar Diesel and lots of improvements. Versatile, easily managed rig with a spacious livable interior. She is cleaned up and ready to sail. -

Oceanis 41.1

Oceanis 41.1 General Equipment list - Europe GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS________________________ • L.O.A 12,43m 40’9’’ • Hull length 11,98m 39’4’’ • L.W.L. 11,37m 37’4’’ • Beam 4,20m 13’9’’ • Deep draft 2,19m 7’2’’ • Deep ballast weight 2 300kg 5,071 lbs • Shallow draft 1,68m 5’6’’ • Shallow ballast weight 2 537kg 5,592 lbs • Air draft 18,86m 61’11’’ • Light displacement 7 836kg 17,271 lbs • Fuel capacity 200L 53 US Gal • Fresh water capacity (standard) 240L 63 US Gal • Fresh water capacity (option) 330L 87 US Gal • Engine power 45 HP 45 HP ARCHITECTS / DESIGNERS ________________________ • Naval Architect: Finot - Conq And associes • Outside & interior design: Nauta Design EC CERTIFICATION _______________________________ • Category A - 8 people • Category B - 9 people • Category C - 12 people STANDARD SAIL LAYOUT AND AREA _______________ • Mainsail (Classic) 40m² 430 sq ft • Mainsail (Furler) 33m² 355 sq ft 2 cabins 1 head version: • Genoa (106 %) 42m² 452 sq ft • Code 0 78,30m² 843 sq ft • Self-tacking jib 33m² 355 sq ft • Asymmetric spinnaker 129m² 1,388 sq ft • Staysail (On furler) 20,90m² 225 sq ft •I 16,03m 52’7’’ •J 5,17m 17’ •P 15,40m 50’6’’ •E 4,71m 15’5’’ 2 cabins 2 heads version 3 cabins 1 head version 3 cabins 2 heads version June 10, 2019 - (non-binding document) Code Bénéteau V12621 (G) Eng Oceanis 41.1 General Equipment list - Europe STANDARD EQUIPMENT MOORING LINES - MOORING • Self-draining chain locker - Clench bolt - Hatch cover CONSTRUCTION _________________________________ • Single roller stainless steel bow fitting with -

Further Devels'nent Ofthe Tunny

FURTHERDEVELS'NENT OF THETUNNY RIG E M H GIFFORDANO C PALNER Gi f ford and P art ners Carlton House Rlngwood Road Hoodl ands SouthamPton S04 2HT UK 360 1, lNTRODUCTION The idea of using a wing sail is not new, indeed the ancient junk rig is essentially a flat plate wing sail. The two essential characteristics are that the sail is stiffened so that ft does not flap in the wind and attached to the mast in an aerodynamically balanced way. These two features give several important advantages over so called 'soft sails' and have resulted in the junk rig being very successful on traditional craft. and modern short handed-cruising yachts. Unfortunately the standard junk rig is not every efficient in an aer odynamic sense, due to the presence of the mast beside the sai 1 and the flat shapewhich results from the numerousstiffening battens. The first of these problems can be overcomeby usi ng a double ski nned sail; effectively two junk sails, one on either side of the mast. This shields the mast from the airflow and improves efficiency, but it still leaves the problem of a flat sail. To obtain the maximumdrive from a sail it must be curved or cambered!, an effect which can produce over 5 more force than from a flat shape. Whilst the per'formanceadvantages of a cambered shape are obvious, the practical way of achieving it are far more elusive. One line of approach is to build the sail from ri gid componentswith articulated joints that allow the camberto be varied Ref 1!. -

Jan 2 2016 Magazine Issue 37

www.classic-yacht.asn.au Issue 37 - January 2016 - Classic Yacht Association of Australia Magazine CONTENTS CYAA REPRESENTATIVES 2 NEW MEMBERS 2 COMING EVENTS 2 SAYONARA and RAWHITI 3 CUP REGATTA 2015 4 AUSTRALIAN HISTORIC 6 VESSELS REGISTER A MAN and HIS BOATS 8 AUSTRALIAN WOODEN 22 BOAT FESTIVAL ST. HELENA CUP REGATTA 28 MANLY WYNNUM YC Q’LD I BUILT A TUMLARE` FOR £350 32 CLASSIC YACHT FOR SALE 34 CYAA MEMBERSHIP 36 APPLICATION Our aim is to promote the appreciation and participation of sailing classic yachts in Australia, and help preserve the historic and cultural significance of these unique vessels. Classic Yacht Association of Australia CYAA REPRESENTATIVES NEW MEMBERS ADMINISTRATION Janet Dean Vic Crew Dingo CYAA Christopher Lawrence Vic Crew Snow Goose PO Box 335 Williamstown Geoff Thorn Vic Crew Martini Victoria 3016 Chris Havre Vic Boat owner Akuna admin@classic‑yacht.asn.au Charlie Boyes Vic Crew Martini QUEENSLAND Mal Botterill Vic Crew Avian Greg Doolan David Brodziak Vic Crew Ettrick Mobile 0418 12 12 02 [email protected] Peter Denniston Vic Boat owner Te Uira http://tradboatsqld.asn.au/ Chris Clapp Vic Crew Fair Winds Robert Kalkman Vic Boat owner Enterprise MAGAZINE EDITORIAL Tim Boucaut Vic Boat owner Warringa Peter Costolloe Deb McKay Vic Crew Warringa Mobile 0419 171 011 [email protected] Dennis Horne Vic Crew Warringa Sam Cowell Vic Crew Warringa Roger Dundas Mobile 0419 342 144 Sam Daniel Vic Crew Mercedes 111 [email protected] Doug McLean Vic Crew Tandanya Michael Daddo Vic Crew Mercedes 111 CYAA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Noel Sutcliffe Vic Crew Trim President Martin Ryan Mercedes III COMING EVENTS Vice President Cameron Dorrough Bungoona Secretary Ian Rose Cyan 2016 Yanmar Wooden Boat Shop Wooden Boat Festival of Geelong. -

1989 Yearbook.Searchable.Pdf

~ ~_¢`-.=Y- ¢W@;~ ~ V/f, >sf>:¢~h~.%».,>;<,¢»£1¢q§,@-:¢»*&w"'f'/@f, ,~,,/_ ¢.-./~»-g-¢a'<-¢¢~f/»~1>.~# 2"*¢_- T§'2? "`_,_<`,_ < \._.\_ \ \ » ~ f;f,>;:~>z_<~ \ 75:1 ~#~ \ _ §___,>»»_\~f&,_< QQ* '\'»;K ' <=:~§ 1_- ~ :;:,~>_f ¢/ =»§~_~ _~_ .\_\ ~@y,_,@ _;~_ ,_ ,,,, _ , ,_ ._ ,_ ~ +;,~»w _"".---svnA . ~_;;_->»~S;;¢=_<___% _'2;; - -~Y _ ~» wf Q»»_¢~ ~»~~ *» -V;-f -w nf?-~f ~.w_,f__- -~,.__. , ._-_,m um _,W~~»f;_ f ~ 'V ~ T31 _ ::?'v ,J Q-mwa.-<»»» ¢~ þÿ3-°'> ¬'1 ' _,MM ~...,, ~, , M _ _WM%_,_ _ ~ ,, _#wap Z= _ f ~ 5`V" Fi? ,,__ _ ""' ff ~ 2 %?5Q<§ _ ' / _ W- = .,¢;.m~ __ 1 ._ ,__.M. §;fQ_5_A ;~W_&%_@____- ~ ~ §§ ;§1 ,, ~=_¢=_`»,_=,__AA2Q_ M- ,» -» ' ` ':' "1 T21 % Qra ii $5 El. A'i:"<"5 ~, '§ f <§' ROCHESTER @ /`¢>§§ ff " \/¢@=" __._, ____ __ Q _ef/> MQW Q {v»f>-;z 1° MMM1 T ~ W 1 ` ,_ 2 *v§_~Q»% ' __A xr 3 4 : ""/ ~ -5`\v;» _,qw ' ~>f~ * »"=* »i'?§'5"; _ ¢,- /` $2 M`\_ _QQ ~C"\`@ '" Q 1 Q § ~ 1 a$s§ ~°f'"1£@@»,. CLUB "\ -\\a~=;<»¢.~ _ $2 ' _ ~ _ / ~\_» ,_- ._ _ E§ ,\ '<:&i` Q ,-fm- 5 _ _r_ /i; '3'" _ """ ` ~ _ _ < _ 5_F ~, LW __ ____,;;§, _,_ _ , \ _§2 1989 ~ _;= % ~` :: ;; @zf'!, ,,-,M » _ L`v ; _@;v~>_~~ `ii?-@» __ __ _ ._ \-§. ~@. ,, _W -f mm T f ` z_ » ;'-H<»;§=» þÿ§ ¬¢ ""?"'»1'f3' ~ @ _ ._ ; ¢@;; _ ,_ , " *1*=*1?* _ ~~ . ;l _ ,W__,,_.