A New Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO

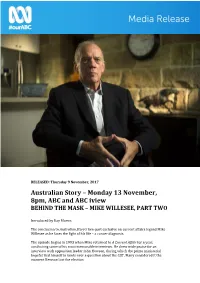

RELEASED: Thursday 9 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO Introduced by Ray Martin. The conclusion to Australian Story’s two-part exclusive on current affairs legend Mike Willesee as he faces the fight of his life – a cancer diagnosis. The episode begins in 1993 when Mike returned to A Current Affair for a year, conducting some of his most memorable interviews. He drew wide praise for an interview with opposition leader John Hewson, during which the prime ministerial hopeful tied himself in knots over a question about the GST. Many considered it the moment Hewson lost the election. Four weeks later praise turned to condemnation when Mike interviewed two young children held captive by killers during the Cangai siege. “I think this is a classic case where we misjudged the audience reaction,” admits former Nine news chief Peter Meakin. Tiring of nightly current affairs, Mike turned his attention to a variety of business interests and documentary making. While in Kenya on his way to film in Sudan he had a premonition that the small plane he was boarding would crash. Shortly after take-off, it did. Although Mike was unhurt, the experience had a profound impact on him and led him on a long journey back to the Catholic faith of his childhood. In the years since he has invested much of his time into trying to find scientific proof for various religious miracles. It is Mike’s strong religious faith, along with the support of his family, that has helped him since being diagnosed with cancer in October last year. -

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

Vertical Motions of Australia During the Cretaceous

Basin Research (1994) 6,63-76 The planform of epeirogeny: vertical motions of Australia during the Cretaceous Mark Russell and Michael Gurnis* Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1063,USA ABSTRACT Estimates of dynamic motion of Australia since the end of the Jurassic have been made by modelling marine flooding and comparing it with palaeogeographical reconstructions of marine inundation. First, sediment isopachs were backstripped from present-day topography. Dynamic motion was determined by the displacement needed to approximate observed flooding when allowance is made for changes in eustatic sea-level. The reconstructed inundation patterns suggest that during the Cretaceous, Australia remained a relatively stable platform, and flooding in the eastern interior during the Early Cretaceous was primarily the result of the regional tectonic motion. Vertical motion during the Cretaceous was much smaller than the movement since the end of the Cretaceous. Subsidence and marine flooding in the Eromanga and Surat Basins, and the subsequent 500 m of uplift of the eastern portion of the basin, may have been driven by changes in plate dynamics during the Mesozoic. Convergence along the north-east edge of Australia between 200 and 100 Ma coincides with platform sedimentation and subsidence within the Eromanga and Surat Basins. A major shift in the position of subduction at 140Ma was coeval with the marine incursion into the Eromanga. When subduction ended at 95 Ma, marine inundation of the Eromanga also ended. Subsidence and uplift of the eastern interior is consistent with dynamic models of subduction in which subsidence is generated when the dip angle of the slab decreases and uplift is generated when subduction terminates (i.e. -

Government and Indigenous Australians Exclusionary Values

Government and Indigenous Australians Exclusionary values upheld in Australian Government continue to unjustly prohibit the participation of minority population groups. Indigenous people “are among the most socially excluded in Australia” with only 2.2% of Federal parliament comprised of Aboriginal’s. Additionally, Aboriginal culture and values, “can be hard for non-Indigenous people to understand” but are critical for creating socially inclusive policy. This exclusion from parliament is largely as a result of a “cultural and ethnic default in leadership” and exclusionary values held by Australian parliament. Furthermore, Indigenous values of autonomy, community and respect for elders is not supported by the current structure of government. The lack of cohesion between Western Parliamentary values and Indigenous cultural values has contributed to historically low voter participation and political representation in parliament. Additionally, the historical exclusion, restrictive Western cultural norms and the continuing lack of consideration for the cultural values and unique circumstances of Indigenous Australians, vital to promote equity and remedy problems that exist within Aboriginal communities, continue to be overlooked. Current political processes make it difficult for Indigenous people to have power over decisions made on their behalf to solve issues prevalent in Aboriginal communities. This is largely as “Aboriginal representatives are in a better position to represent Aboriginal people and that existing politicians do not or cannot perform this role.” Deeply “entrenched inequality in Australia” has led to the continuity of traditional Anglo- Australian Parliamentary values, which inherently exclude Indigenous Australians. Additionally, the communication between the White Australian population and the Aboriginal population remains damaged, due to “European contact tend[ing] to undermine Aboriginal laws, society, culture and religion”. -

Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE

RELEASED: Thursday 2 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE An inimitable presence on our TV screens for 50 years, Mike Willesee now faces his greatest challenge – a diagnosis of throat cancer. In a two-part exclusive, Australian Story looks back over the extraordinary life of one of broadcasting’s more enigmatic characters. Born in Perth, Mike was profoundly influenced by the family’s strong Catholic faith and his father’s involvement in politics. “I went to John Curtin’s funeral and I sat on Ben Chifley’s knee and Gough Whitlam watched me play football so I guess by osmosis if nothing else I was learning about politics,” Mike says. As a 10-year-old, Mike was sent briefly to the notorious Bindoon Boy’s Town by his father in order to toughen him up. It was a brutal experience. “I still don't know why my father thought I needed to toughen up,” Mike says, “but I did toughen up. You know, it changed me.” Later, a split within the Labor party saw the family ostracised by the Catholic church. His father was railed against from the pulpit and Mike was forced out of school a year early by the Catholic brothers who taught him. These events, and an emerging interest in girls, saw Mike turn his back on the church. After school, Mike fell into journalism, working for papers in Perth and Melbourne before ending up in Canberra. When the ABC launched the ground- breaking current affairs program This Day Tonight, he found himself in the right place at the right time. -

South Australian State Public Sector Organisations

South Australian state public sector organisations The entities listed below are controlled by the government. The sectors to which these entities belong are based on the date of the release of the 2016–17 State Budget. The government’s interest in each of the public non-financial corporations and public financial corporations listed below is 100 per cent. Public Public General Non-Financial Financial Government Corporations Corporations Sector Sector Sector Adelaide Cemeteries Authority * Adelaide Festival Centre Trust * Adelaide Festival Corporation * Adelaide Film Festival * Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources * Management Board Adelaide Venue Management Corporation * Alinytjara Wilurara Natural Resources Management Board * Art Gallery Board, The * Attorney-General’s Department * Auditor-General’s Department * Australian Children’s Performing Arts Company * (trading as Windmill Performing Arts) Bio Innovation SA * Botanic Gardens State Herbarium, Board of * Carrick Hill Trust * Coast Protection Board * Communities and Social Inclusion, Department for * Correctional Services, Department for * Courts Administration Authority * CTP Regulator * Dairy Authority of South Australia * Defence SA * Distribution Lessor Corporation * Dog and Cat Management Board * Dog Fence Board * Education Adelaide * Education and Child Development, Department for * Electoral Commission of South Australia * Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Department of * Environment Protection Authority * Essential Services Commission of South Australia -

C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos

C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos 7 ELEVEN 1.eps 7 ELEVEN 2.eps 7UP 1.eps 7UP 2.eps 7UP CHERRY 1.eps 7UP CHERRY 2.eps 7UP DIET 1.eps 7UP DIET 2.eps 7UP DIET CHERR... 7UP DIET CHERR... S & H GREEN STA... SAA.eps SAAB AUTOMOBIL... SAAB AUTOMOBIL... SABENA AIR 1.eps SABENA AIR 2.eps SABENA WORLD ... SABRE BOATS.eps SACHS.eps SAFE PLACE.eps SAFECO.eps SAFEWAY 1.eps SAFEWAY 2.eps SAINSBURYS 1.eps SAINSBURYS 2.eps SAINSBURYS BAN... SAINSBURYS BAN... SAINSBURYS HO... SAINSBURYS HO... SAINSBURYS SAV... Page 1 C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos SAINSBURYS SAV... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SALEM.eps SALOMON.eps SALON SELECTIV... SALTON.eps SALVATION ARMY... SAMS CLUB.eps SAMS NET.eps SAMS PUBLISHIN... SAMSONITE.eps SAMSUNG 1.eps SAMSUNG 2.eps SAN DIEGO STAT... SAN DIEGO UNIV ... SAN DIEGO UNIV ... SAN JOSE UNIV 1.... SAN JOSE UNIV 2.... SANDISK 1.eps SANDISK 2.eps SANFORD.eps SANKYO.eps SANSUI.eps SANYO.eps SAP.eps SARA LEE.eps SAS AIR 1.eps SAS AIR 2.eps Page 2 C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos SASKATCHEWAN ... SASSOON.eps SAT MEX.eps SATELLITE DIREC... SATURDAY MATIN... SATURN 1.eps SATURN 2.eps SAUCONY.eps SAUDI AIR.eps SAVIN.eps SAW JAMMER PR... SBC COMMUNICA... SC JOHNSON WA... SCALA 1.eps SCALA 2.eps SCALES.eps SCCA.eps SCHLITZ BEER.eps SCHMIDT BEER.eps SCHWINN CYCLE... SCIFI CHANNEL.eps SCIOTS.eps SCO.eps SCORE INT'L.eps SCOTCH.eps SCOTIABANK 1.eps SCOTIABANK 2.eps SCOTT PAPER.eps SCOTT.eps SCOTTISH RITE 1... -

An Introduction to the Life and Work of Amy Witting

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship... 'GOLD OUT OF STRAW': AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF AMY WITTING Yvo nne Miels - Flin ders University It is rather unusual for anyone to be in their early seventies before being recognised as a writer of merit. In this respect Amy Wining must surely be unique amongst Australian writers. Although she has been writing all her life, she was 71 when her powerful novel I for Isabel was published, in late 1989. This novel attracted considerable critical attention, and since then most of the backlog of stories and poetry written over a lifetime have been published. The 1993 Patrick White Award followed and she became known to a wider readership. The quality and sophistication of her work, first observed over fifty years ago, has now been generally acknowledged. Whilst Witting has been known to members of the literary community in New South Wales for many years, her life and work have generally been something of a literary mystery. Like her fictional character Fitzallan, the ·undiscovered poet' in her first novel Th e Visit ( 1977). her early publications were few, and scattered in Australian literary journals and short-story collections such as Coast to Coast. While Fitzallan's poetry was 'discovered' forty years after his death, Witting's poetry has been discovered and published, but curiously, it is absent from anthologies. For me, the 'mystery' of Amy Witting deepened when the cataloguing in-publication details in a rare hard-back copy of Th e Visit revealed the author as being one Joan Levick. -

University of Canberra Annual Report 2009 2009 Rra Anbe Y Ive Rist Un of C S) O

UNIVERISTY 2009 2009 ANNUAL OF CANBERRA REPORT ANNUAL U N I VE RSIT Y OF C A N B E RRA ANNU A L REPO RT 2009 REPORT THE UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA CANBERRA ACT 2601 AUSTRALIA T 1800 UNI CAN (1800 864 226) F (02) 6201 5445 E [email protected] www.canberra.edu.au Australian Government Higher Education (CRICOS) Provider; University of Canberra #00212K, University of Canberra College #01893E. Information in this guide was correct at time of printing. The University of Canberra reserves the right to change course offerings, arrangements, and all other aspects without notice. Up-to-date information will be available on the University’s website www.canberra.edu.au as changes are accredited by Academic Board. Printed 2010 Enquiries concerning this report may be addressed to: Secretary of Council University of Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone +61 2 6201 2051 Facsimile +61 2 6201 5381 www.canberra.edu.au Copyright University of Canberra, 2010 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the University. Published by: University of Canberra, Secretariat Design: Butler Creative ISSN 1325-1627 University of Canberra # 00212K University of Canberra College #00095K ANNUAL REPORT 2009 i LETTER TO THE miNisTER University of Canberra April 2010 Dear Minister In accordance with Section 36 of the University of Canberra Act 1989, we present the Report by the Council of the operation of the University of Canberra for the period 1 January to 31 December 2009, together with financial statements in respect of that period. -

Tasmania (TAS)

Australian Red Cross 26.05.21 COVID-19 Information Sheet – Tasmania (TAS) Disclaimer: The information below should not be considered an exhaustive list and service delivery may change. Please contact organisations and services directly for the most up to date information and to enquire further about eligibility. Red Cross does not determine eligibility for the third party services listed. Government of Tasmania Updates • Tasmanian Government COVID-19 Updates o Tasmanian border restrictions and subsequent quarantine arrangements are classified as low, medium and high. To check the classification of a location visit the Tasmanian government’s coronavirus website. These classifications change depending on the COVID-19 situation in each state and territory. • COVID-19 vaccinations: The Tasmanian and the Australian Governments are working together to give safe COVID-19 vaccinations to the community. Vaccines are being delivered in phases. All Tasmanians aged 18 and over will be able to get vaccinated for free. More information is available on the Tasmanian government website. • Support for Temporary Visa Holders: • Pandemic Isolation Assistance Grants are available to support low-income persons, casual workers and self-employed persons who are required to self-isolate due to COVID-19 risk. To apply, please call the Public Health Hotline on 1800 671 738. • The Rapid Response Skills Initiative provides funding of up to $3,000 towards the cost of training for people who have lost their jobs because they have been made redundant, the place they -

Voting in AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents

Voting IN AUSTRALIAAUSTRALIA Contents Your vote, your voice 1 Government in Australia: a brief history 2 The federal Parliament 5 Three levels of government in Australia 8 Federal elections 9 Electorates 10 Getting ready to vote 12 Election day 13 Completing a ballot paper 14 Election results 16 Changing the Australian Constitution 20 Active citizenship 22 Your vote, your voice In Australia, citizens have the right and responsibility to choose their representatives in the federal Parliament by voting at elections. The representatives elected to federal Parliament make decisions that affect many aspects of Australian life including tax, marriage, the environment, trade and immigration. This publication explains how Australia’s electoral system works. It will help you understand Australia’s system of government, and the important role you play in it. This information is provided by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), an independent statutory authority. The AEC provides Australians with an independent electoral service and educational resources to assist citizens to understand and participate in the electoral process. 1 Government in Australia: a brief history For tens of thousands of years, the heart of governance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was in their culture. While traditional systems of laws, customs, rules and codes of conduct have changed over time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to share many common cultural values and traditions to organise themselves and connect with each other. Despite their great diversity, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities value connection to ‘Country’. This includes spirituality, ceremony, art and dance, family connections, kin relationships, mutual responsibility, sharing resources, respecting law and the authority of elders, and, in particular, the role of Traditional Owners in making decisions. -

SL MAGAZINE Winter 2018 State Library of New South Wales NEWS

–Winter 2018 Vanessa Berry goes underground Message Since I last wrote to you, the Library has lost one of its greatest friends and supporters. You can read more about Michael Crouch’s life in this issue. For my part, I salute a friend, a man of many parts, and a philanthropist in the truest sense of the word — a lover of humanity. Together with John B Fairfax, Sam Meers, Rob Thomas, Kim Williams and many others, he has been the enabling force behind the transformation currently underway at the Library. Roll on October, when we can show you what the fuss is about. Our great Library, as it stands today, is the result of nearly 200 years of public and private partnerships. It is one of the NSW Government’s most precious assets, but much of what we do today would be impossible without additional private support. The new galleries in the Mitchell Building are only one example of this. Our Foundation is currently supporting many other projects, including Caroline Baum’s inaugural Readership in Residence, our DX Lab Fellow Thomas Wing-Evans’ ground-breaking work, the Far Out! educational outreach program, the National Biography Award, the Sydney Harbour Bridge online exhibition (currently in preparation), not to mention the preservation and preparation of our oil paintings for the major hang later this year. All successful institutions need to have a clear idea of what they stand for if they are to continue to attract support from both government and private benefactors. At the first ‘Dinner with the State Librarian’ on 12 April, I addressed an audience of more than 100 supporters about the Library in its long-term historical context — stressing the importance of preserving both oral and written traditions in our collections and touching on the history we share with museums.