Citigroup: a Report on CSR Policy and Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stipulation and Consent to Issuance of an Order of Prohibition, Lenard

- I Y I ” .., UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Before The l OFFICE OF THRIFT SUPERVISION In the Matter of ; OTS Order No. SF-97-007 LENARD CAWTA. j Dated: -oh 88. 1997 Former Employee and Institution-Affiliated Party of CALIFORNIA FEDERAL BANK, A F.S.B.; San Francisco, California. ! I STIPULATION AND CONSENT TO ISSUANCE OF AN ORDER OF PROHIBITION WHEREAS, the Office of Thrift Supervision ("OTS"), based upon information derived from the exercise of its regulatory responsibilities, has informed Lenard Canta ("CAWTA"), a former employee and institution-affiliated party of California Federal Bank, a F.S.B. ("CalFed" or "the Association"), OTS No. 5099, that the OTS is of the opinion that the grounds exist to initiate an administrative prohibition proceeding against CAWTA pursuant to 12 U.S.C. B 1818(e)'; and WHEREAS, CAWTA desires to cooperate with the OTS to avoid the time and expense of such administrative litigation and, without admitting or denying that such grounds exist, but admitting the statements and conclusions in Paragraph 1 below, hereby stipulates and agrees to the following terms: 'All references in this Stipulation and Consent and the Order of Prohibition to the U.S.C. are as amended. - _I 1. Jurisdiction. l (a) CalFed, at all times relevant hereto, was a "savings association" within the meaning of 12 U.S.C. § 1813(b) and Section 2(4) of the Home Owners' Loan Act, 12 U.S.C. 0 1462(4). Accordingly, CalFed is an "insured depository institution" as that term is defined in 12 U.S.C. § 1813(c). (b) CANTA, as a former employee of CalFed, isdeemed to be an "institution-affiliated party" as that term is defined in (12 U.S.C. -

2016 National Interagency Community Reinvestment Conference

February 7-10, 2016 Los Angeles, CA Sponsored by Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Office of the Comptroller of the Currency Community Development Financial Institutions Fund JW Marriott at L.A. Live 900 West Olympic Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90015 213-765-8600 Conference Registration Diamond Ballroom Plaza To Conference Ballrooms Ź Studio 3 Atrium Platinum Ballroom Olympic Studios 1, 2 Gold Ballroom 2 elcome to the 2016 National Interagency Community Reinvestment Conference and [V3VZ(UNLSLZHJP[`[OH[L_LTWSPÄLZIV[O[OLJOHSSLUNLZHUKVWWVY[\UP[PLZMHJPUN[OL Wcommunity development sector. Economic opportunity does not happen in a vacuum: it takes a coordinated approach to housing, LK\JH[PVUW\ISPJZHML[`OLHS[OJHYL[YHUZWVY[H[PVUHUKQVIZ6]LY[OLUL_[[OYLLKH`Z^L^PSS L_WSVYL[OLWH[O^H`Z[VVWWVY[\UP[`[OH[JHUJYLH[L]PIYHU[ULPNOIVYOVVKZMVYHSS(TLYPJHUZ >OL[OLY`V\»YLHIHURLYKL]LSVWLYVYJVTT\UP[`SLHKLY^LOVWL`V\^PSS[HRLM\SSHK]HU[HNLVM [OLSLHYUPUNHUKUL[^VYRPUNVWWVY[\UP[PLZ[OPZJVUMLYLUJLVMMLYZ;OLCRA Compliance track features an interagency team of top examiners from around the country. Sessions in this track cover virtually L]LY`HZWLJ[VM[OL*9(L_HTPUH[PVUWYVJLZZMVYHSSPUZ[P[\[PVUZPaLZHUKPUJS\KLILZ[WYHJ[PJLZ[OH[ L]LU[OLTVZ[L_WLYPLUJLK*9(VMÄJLYZ^PSSÄUK\ZLM\S ;OLZLZZPVUZPU[OLCommunity Development Policy and Practice trackOPNOSPNO[PUUV]H[P]LÄUHUJPUN Z[Y\J[\YLZZ[YH[LNPLZHUKWHY[ULYZOPWTVKLSZHPTLKH[I\PSKPUNWH[O^H`Z[VLJVUVTPJVWWVY[\UP[` PUSV^LYPUJVTLJVTT\UP[PLZ-VY^L»]LHKKLKHZLYPLZVM^VYRZOVWZLZZPVUZKLZPNULK[VIL ZRPSSI\PSKPUNVWWVY[\UP[PLZMVYWHY[PJPWHU[Z -

US Accounts in 24 Hours

U.S. Accounts In 24 Hours - eBook Thank you for purchasing our featured "U.S. Accounts In 24 Hours" eBook / Online Information Packet offered at our web site, U.S. Account Setup.com Within our featured online information packet, you will find all of the resources, tools, information, and contacts you'll need to quickly & easily open a NON-U.S. Resident Bank Account within 24 hours. You'll find lists of U.S. Banks, Account Application Forms, Information on how to obtain a U.S. Mailing Address, plus so much more. Just point and click your way through our Online Information Packet using the links above. If you should have any questions or experience any difficulties in opening your Non-U.S. Resident Account, please feel free to email us at any time, and one of our representatives will get back with you promptly. For Support, Email: [email protected] Homepage: www.usaccountsetup.com Application Forms UPDATE - E-TRADE'S NEW ACCOUNT OPENING POLICIES Etrade is changed the rules in which they open International Banking/ Brokerage accounts for foreigners. They now require all new applications be submitted to the local branch office in your region. Once account is opened, you will be able to use it as a U.S. Bank/Brokerage Account out of your home country. Below, you will find a list of International Etrade Phone Numbers & Addresses. Contact the etrade office that best reflects where you reside or would like your account based out of and where you would like to receive your debit card. U.S. -

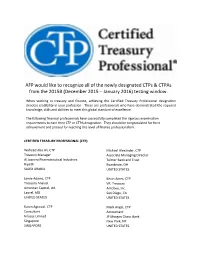

AFP Would Like to Recognize All of the Newly Designated Ctps & Ctpas

AFP would like to recognize all of the newly designated CTPs & CTPAs from the 2015B (December 2015 – January 2016) testing window. When working in treasury and finance, achieving the Certified Treasury Professional designation denotes credibility in your profession. These are professionals who have demonstrated the required knowledge, skills and abilities to meet this global standard of excellence. The following financial professionals have successfully completed the rigorous examination requirements to earn their CTP or CTPA designation. They should be congratulated for their achievement and praised for reaching this level of finance professionalism. CERTIFIED TREASURY PROFESSIONAL (CTP) Waheed Abu Ali, CTP Michael Alexander, CTP Treasury Manager Associate Managing Director Al Jazeera Pharmaceutical Industries Talmer Bank and Trust Riyadh Boardman, OH SAUDI ARABIA UNITED STATES Jamie Adams, CTP Kevin Ames, CTP Treasury Analyst VP, Treasury American Capital, Ltd. Amobee, Inc. Laurel, MD San Diego, CA UNITED STATES UNITED STATES Karan Agrawal, CTP Mark Angel, CTP Consultant Accountant Infosys Limited JP Morgan Chase Bank Singapore New York, NY SINGAPORE UNITED STATES Alexandru Anton, CTP Rishi Bajaj, CTP Treasurer Director Rompetrol Sa Sofina Foods Inc. Navodari Mississauga, ON ROMANIA CANADA Spiridoula Arceo, CTP Lisa Balfe, CTP Vice President Director First American Bank Corporation Commonwealth Bank Of Australia Elk Grove Village, IL New York, NY UNITED STATES UNITED STATES Frank Armocida, CTP Jenny Barahona, CTP Director Securities -

Collections and Crime Ons and Crime: the Case of Citibank in Indonesia

Journal of Business Cases and Applications Collecti ons and crime : the case of Citibank in Indonesia Michael Martin University of Northern Colorado Joseph J. French University of Northern Colorado ABSTRACT The principal subject matter of this study involves the operation of multinational businesses , international law, and business ethics. This case study describes several hypothetical dilemmas, both overt and subtle, our fictitious corporate officer at Citibank International must appropriately address. This case describes several modern s candals faced by Citibank’s operations in Jakarta, Indonesia. These scandals range from the embezzlement of millions of dollars by a Citigold manager to the tragic collections related death of a Citibank credit card holder. This case provides a detailed ba ckground on the Indonesian business climate, discussion of applicable domestic and international laws, as well as analysis of appropriate ethical frameworks and decision making. Key Words : Business Ethics, Banking, International law, Case Study Collections and crime, Page 1 Journal of Business Cases and Applications INTRODUCTION Matt Lelander lets out a big sigh as he approaches the bar in the bu siness lounge of San Francisco International airport. Matt is returning from a banking conference in Vancouver, Canada and was hoping to make it home before a late night FedEx package and e -mail changed his plans. As he pours himself a full g lass of local California wine Matt carefully contemplates recent events. Matt is an operations and ethics officer for Citib ank’s international division and was recently assigned to monitor Citib ank’s operations in Indonesia. Mr. Lelander is considered a rising star in the banking world and many believe he will soon be sitting on Citigroup’s board of directors. -

EMS Counterparty Spreadsheet Master

1 ECHO MONITORING SOLUTIONS COUNTERPARTY RATINGS REPORT Updated as of October 24, 2012 S&P Moody's Fitch DBRS Counterparty LT Local Sr. Unsecured Sr. Unsecured Sr. Unsecured ABN AMRO Bank N.V. A+ A2 A+ Agfirst Farm Credit Bank AA- AIG Financial Products Corp A- WR Aig-fp Matched Funding A- Baa1 Allied Irish Banks PLC BB Ba3 BBB BBBL AMBAC Assurance Corporation NR WR NR American International Group Inc. (AIG) A- Baa1 BBB American National Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago (see JP Morgan Chase Bank) Assured Guaranty Ltd. (U.S.) A- Assured Guaranty Municipal Corp. AA- Aa3 *- NR Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited AA- Aa2 AA- AA Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, S.A. BBB- Baa3 *- BBB+ A Banco de Chile A+ NR NR Banco Santander SA (Spain) BBB (P)Baa2 *- BBB+ A Banco Santander Chile A Aa3 *- A+ Bank of America Corporation A- Baa2 A A Bank of America, NA AA3AAH Bank of New York Mellon Trust Co NA/The AA- AA Bank of North Dakota/The AA- A1 Bank of Scotland PLC (London) A A2 A AAL Bank of the West/San Francisco CA A Bank Millennium SA BBpi Bank of Montreal A+ Aa2 AA- AA Bank of New York Mellon/The (U.S.) AA- Aa1 AA- AA Bank of Nova Scotia (Canada) AA- Aa1 AA- AA Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubish UFJ Ltd A+ Aa3 A- A Bank One( See JP Morgan Chase Bank) Bankers Trust Company (see Deutsche Bank AG) Banknorth, NA (See TD Bank NA) Barclays Bank PLC A+ A2 A AA BASF SE A+ A1 A+ Bayerische Hypo- und Vereinsbank AG (See UniCredit Bank AG) Bayerische Landesbank (parent) NR Baa1 A+ Bear Stearns Capital Markets Inc (See JP Morgan Chase Bank) NR NR NR Bear Stearns Companies, Inc. -

Collections and Crime: the Case of Citibank in Indonesia

Journal of Business Cases and Applications Collections and crime: The case of Citibank in Indonesia Michael Martin University of Northern Colorado Joseph J. French University of Northern Colorado ABSTRACT The principal subject matter of this study involves the operation of multinational businesses, international law, and business ethics. This case study describes several hypothetical dilemmas, both overt and subtle, our fictitious corporate officer at Citibank International must appropriately address. This case describes several modern scandals faced by Citibank’s operations in Jakarta, Indonesia. These scandals range from the embezzlement of millions of dollars by a Citigold manager to the tragic collections related death of a Citibank credit card holder. This case provides a detailed background on the Indonesian business climate, discussion of applicable domestic and international laws, as well as analysis of appropriate ethical frameworks and decision making. Keywords: Business Ethics, Banking, International law, Case Study Copyright statement: Authors retain the copyright to the manuscripts published in AABRI journals. Please see the AABRI Copyright Policy at http://www.aabri.com/copyright.html. Collections and crime, page 1 Journal of Business Cases and Applications INTRODUCTION Matt Lelander lets out a big sigh as he approaches the bar in the business lounge of San Francisco International airport. Matt is returning from a banking conference in Vancouver, Canada and was hoping to make it home before a late night FedEx package and e-mail changed his plans. As he pours himself a full glass of local California wine Matt carefully contemplates recent events. Matt is an operations and ethics officer for Citibank’s international division and was recently assigned to monitor Citibank’s operations in Indonesia. -

Citigroup Inc. 10-Q 3Rd Quarter 2002

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 FORM 10-Q QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended September 30, 2002 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ________ to _______ Commission file number 1-9924 Citigroup Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 52-1568099 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 399 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10043 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (212) 559-1000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes x No Indicate the number of shares outstanding of each of the issuer’s classes of common stock as of the latest practicable date: Common stock outstanding as of October 31, 2002: 5,056,767,896 Available on the Web at www.citigroup.com Citigroup Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Part I − Financial Information Item 1. Financial Statements: Page No. Consolidated Statement of Income (Unaudited) − Three and Nine Months Ended September 30, 2002 and 2001 47 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position − September 30, 2002 (Unaudited) and December 31, 2001 48 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Stockholders’ Equity (Unaudited) − Nine Months Ended September 30, 2002 and 2001 49 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows (Unaudited) − Nine Months Ended September 30, 2002 and 2001 50 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements (Unaudited) 51 Item 2. -

Citi Indonesia Named As the Best International Bank in Indonesia

Press Release For Immediate Distribution Citi Indonesia Named as The Best International Bank in Indonesia Jakarta, June 2, 2020 - Citi Indonesia (Citibank, N.A., Indonesia) has been named as Best International Bank in Indonesia from one of the leading financial publication in Asia, Finance Asia, during its annual Country Awards 2020. The awards recognizes the best banks, brokers, law firms across Asia and rating agencies in China. On its official website, Finance Asia emphasizes that not only is this year's competition fierce, but it also took place during an unprecedented global backdrop due to the COVID-19 situation. The award also highlighted banks' resilience and their ability to adapt to fast-changing conditions, which includes enabling most of their employees to successfully work from home. Commenting on this achievement, Citi Indonesia CEO Batara Sianturi said, “Among the increasingly competitive and volatile market situation, we are really grateful to receive this award from Finance Asia magazine. This achievement shows our focus and commitment as a global bank, which offers innovative and integrated financial solutions in our line of businesses, namely Institutional Banking and Consumer Banking. Amid ongoing concerns around COVID-19 situation in Indonesia, we want our customers to know that we remain committed to serve them by prioritizing them, to navigate these challenging times together.” In terms of financial performance, Citibank N.A., Indonesia has announced its first quarter 2020 result, where the bank was able to post a net income of Rp 1 Trillion. The bank also recorded a Return on Equity (ROE) of 22.5% and a Return on Assets (ROA) of 5.6% during the same period. -

Data Perusahaan Laporan Tahunan 2008 • PT Bank Danamon Indonesia Tbk 295 Dewan Komisaris

294 PT Bank Danamon Indonesia Tbk • Laporan Tahunan 2008 Data Perusahaan Laporan Tahunan 2008 • PT Bank Danamon Indonesia Tbk 295 Dewan Komisaris J. B. Kristiadi Ng Kee Choe Wakil Komisaris Utama/ Komisaris Utama Komisaris Independen Ng Kee Choe telah menjabat sebagai Komisaris sejak Maret 2004 dan Dr. Kristiadi menjabat sebagai Komisaris sejak tahun 2005. kemudian diangkat sebagai Komisaris Utama dalam RUPST bulan Mei tahun 2006 dan telah menjabat sebagai Komisaris sejak Maret 2004. Beliau memperoleh gelar PhD dari Sorbonne University, Perancis tahun 1979. Saat ini merupakan Chairman Singapore Power Limited dan NTUC Income Insurance Cooperative. Beliau juga duduk dalam Boards of Singapore Saat ini Beliau menjabat sebagai Staf Ahli Menteri Keuangan Republik Exchange Limited dan Singapore Airport Terminal Services Limited. Indonesia Beliau juga pernah menjabat sebagai Vice Chairman dan Direktur DBS Sebelumnya, menjabat sebagai Direktur Pemeliharaan Aset dan Group Holdings Ltd hingga pensiun pada bulan Juni tahun 2003. Direktur Anggaran Kementrian Keuangan RI dan Ketua Lembaga Administrasi Negara RI dari tahun 1990 hingga tahun 1998. Selanjutnya Mendapat penghargaan Public Service Star Award pada bulan Agustus menjabat sebagai Asisten V Menteri Koordinator Bidang Pengawasan, tahun 2001. Pembangunan, dan Pendayagunaan Aparatur Negara sampai tahun 2001, Deputi Menteri Sekretaris Menteri Negara kabinet reformasi Keahlian: sampai tahun 2004, sekertaris menteri Komunikasi dan Informasi hingga Kredit, Keuangan, Sumberdaya Manusia, Tresuri, Manajemen Risiko tahun 2004. Beliau menjabat sebagai Sekretaris Jenderal Departemen Keuangan Republik Indonesia pada tahun 2005-2006. Penugasan Khusus: Anggota Komite Nominasi dan Remunerasi Keahlian: Keuangan, Manajemen Risiko Penugasan Khusus: Ketua Komite Nominasi dan Remunerasi Milan R. Shuster Gan Chee Yen Komisaris Independen Komisaris Milan Robert Shuster, PhD menjabat sebagai Komisaris sejak tahun Gan Chee Yen menjabat sebagai Komisaris sejak tahun 2003. -

Laporan Pelaksanaan Tata Kelola Terintegrasi Integrated Corporate Governance Report Konglomerasi Keuangan Citibank N.A

LAPORAN PELAKSANAAN TATA KELOLA TERINTEGRASI INTEGRATED CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT KONGLOMERASI KEUANGAN CITIBANK N.A. DI INDONESIA FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATION CITIBANK N.A. IN INDONESIA 31 December 2015 INTEGRATED CORPORATE GOVERNANCE TATA KELOLA PERUSAHAAN TERINTEGRASI In the framework to improve the performance Dalam rangka meningkatkan kinerja of Financial Conglomeration and improve the Konglomerasi Keuangan dan meningkatkan compliance towards the laws and regulations kepatuhan terhadap peraturan perundang- as well as the ethical values that are undangan serta nilai-nilai etika yang berlaku applicable in the financial services industry, pada industri jasa keuangan, Konglomerasi Financial Conglomeration shall perform its Keuangan wajib melaksanakan kegiatan business activities based on good Integrated usaha dengan berpedoman pada prinsip Tata Good Corporate Governance principles. Kelola Terintegrasi yang baik. Citibank N.A. Financial Conglomeration in Konglomerasi Keuangan Citibank N.A. di Indonesia consists of Citibank N.A., Indonesia terdiri dari Citibank N.A., Indonesia Indonesia as the Main Entity and PT sebagai Entitas Utama dan PT Citigroup Citigroup Securities Indonesia as the Securities Indonesia sebagi anggota. member. Citibank N.A., Indonesia is established Citibank N.A., Indonesia berdiri berdasarkan pursuant to the Minister of Finance Letter No. Surat Menteri Keuangan No. D.15.6.1.4.23 D.15.6.1.4.23 dated June 14, 1968 to conduct tanggal 14 Juni 1968 untuk commercial bank and foreign exchange menyelenggarakan kegiatan bank umum dan activities. Main activity of Citibank N.A., aktivitas devisa. Aktivitas utama dari Citibank Indonesia is includes Corporate and N.A., Indonesia meliputi aktifitas Corporate Consumer Bank. dan Consumer Bank. PT Citigroup Securities Indonesia has been PT Citigroup Securities Indonesia yang berdiri established since July 3, 1989 owned by sejak 3 Juli 1989 dimiliki oleh Citibank Citibank Overseas Investment Corporation Overseas Investment Corporation (COIC) dan (COIC) and local partner. -

Dawn Haghighi Nomination Page 1 of 10 Nomination for “Outstanding

Nomination For “Outstanding Committee Member of The Year” Is awarded for individual excellence, leadership and major contributions made by a member of an ACC Committee. General Requirements: Eligibility for this award is restricted to current ACC members in good standing who are members of an ACC Committee. Nominees are considered for their committee leadership positions, their contributions to the committee, ACC and the legal profession generally, especially in-house practice. Contributions to the community at large through volunteer work or pro bono activities may also be considered. Please attach additional sheets, as necessary and return your nomination to ACC (attn: Victor Morales at [email protected]). I, Raghu Nandan, hereby nominate the following ACC Member for “Outstanding Committee Member of the Year.” Nominee: Dawn Haghighi Nominee's Company: PCV Murcor Committee Affiliation: Real Estate Committee Please provide a brief summary of the nominee’s leadership role(s) and contributions to the above committee: Please tell us about the nominee’s contributions to ACC (e.g., CLE programs, ACC publications, membership outreach/development, etc.), the legal profession generally and in-house practice specifically (including through other bar association activities which promote the expertise of in-house counsel). Please comment on any community service or pro bono activities on the part of the nominee or any other factors, which you would like to be considered. NOTE: A bio and headshot of winner will be required within two-weeks after selection has been made. Dawn Haghighi Nomination Page 1 of 10 NOMINATION FOR JONATHAN A. SILBER OUTSTANDING COMMITTEE MEMBER OF THE YEAR AWARD As the Vice-Chair of ACC’s Real Estate Committee, I am pleased to nominate Dawn Haghighi, General Counsel of Affiliate Companies PCV Murcor Real Estate Services (Los Angeles), Hightide Settlement Services (Anaheim), and VRM Mortgage Services (Dallas) for the 2017 Jonathan A.