He Took Us to Gallipoli (Recollection)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Acp Bulletin

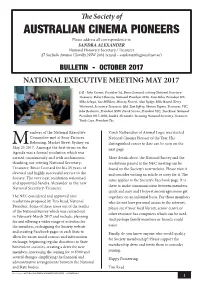

The Society of AUSTRALIAN CINEMA PIONEERS Please address all correspondence to SANDRA ALEXANDER National Honorary Secretary / Treasurer 27 Surfside Avenue Clovelly NSW 2031 (email – [email protected]) BULLETIN - OCTOBER 2017 NATIONAL EXECUTIVE MEETING MAY 2017 L-R - John Cronin, President SA, Bruce Leonard, retiring National Secretary- Treasurer, Robert Slaverio, National President 2016, Alan Stiles, President WA, Mike Selwyn, Sue Milliken, Murray Forrest, Alan Rydge, Mike Baard, Kerry Westwood, Secretary-Treasurer, Qld, Tom Jeffrey, Sharon Tapner, Treasurer, VIC, John Rochester, President NSW, Derek Screen, President VIC, Tim Read, National President 2017-2018, Sandra Alexander, Incoming National Secretary-Treasurer, Yurik Czyz, President Tas. embers of the National Executive Zareh Nalbandian of Animal Logic was elected Committee met at Sony Pictures National Cinema Pioneer of the Year. His Releasing, Market Street Sydney on distinguished career to date can be seen on the MMay 25 2017. Amongst the first items on the next page. Agenda was a formal resolution which was carried unanimously and with acclamation More details about the National Survey and the thanking our retiring National Secretary- resolutions passed at the NEC meeting can be Treasurer, Bruce Leonard for his 25 years of found on the Society’s new website. Please visit it devoted and highly successful service to the and consider writing an article or story for it. The Society. The very next resolution welcomed same applies to the Society’s Facebook page. It is and appointed Sandra Alexander as the new there to make communication between members National Secretary-Treasurer. quick and easy and I hope it encourages more get The NEC considered and approved nine togethers on an informal basis. -

Download Newsletter 23 for August 2011

FRIENDS OF THE NATIONAL FILM AND SOUND ARCHIVE INC NEWSLETTER ISSUE 23 August 2011 Founding Patrons: Gil Brealy, Bryan Brown, Anthony Buckley, Scott Hicks, Patricia Lovell, Chris Noonan, Michael Pate, Fred Schepisi, Albie Thoms Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has. Margaret Mead DEAR FRIENDS, Another year has passed and we are now looking at closer co-operation with the NFSA and seeing how we can assist with the identification of the collections. Contributions to this Newsletter on topics that relate to Australia’s screen and sound communities are most welcome. Later in this Newsletter we have contributions from two Friends Committee members. NEW DIRECTOR OF THE NFSA After a long national and international search process, Michael Loebenstein, film historian and curator from the Austrian Film Archive has been announced as the incoming Director of the NFSA. The Friends look forward to meeting with the new Director and establishing a good working relationship with him, when he takes up his position at the NFSA later in the year. Our thanks go to the Deputy Director Ann Landrigan who has held the fort for the last nine months. A press release was issued by the Minister on 23 June. The original press release can be found by looking at the Minister’s website: New appointments for arts archive body, 23 June, SC085/2011: www.minister.regional.gov.au/sc/releases/2011/june: The National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) will be led by a new chief executive officer and a reinvigorated board following the latest appointments to the popular cultural institution. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. TheVictorian Historical Journal is a refereed journal publishing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. EDITORS Richard Broome, Emeritus Professor, La Trobe University, and Judith Smart, Honorary Associate Professor, RMIT University PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Jill Barnard Rozzi Bazzani Sharon Betridge (Co-editor, History News) Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) (Co-Editor, History News) Marie Clark Jonathan Craig (Reviews Editor) John Rickard John Schauble Judith Smart (Co-editor, History News) Lee Sulkowska Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 291 VOLUME 90, NUMBER 1 JUNE 2019 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2018 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

SCREENING MOTHERS: Representations of Motherhood in Australian Films from 1900 to 1988

SCREENING MOTHERS: Representations of motherhood in Australian films from 1900 to 1988 CAROLINE M. PASCOE B.A. (Honours) M.A. UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 1998 ii The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original, except as acknowledged in the text. The material has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other university. CAROLINE MYRA PASCOE iii ABSTRACT Although the position of mothers has changed considerably since the beginning of the twentieth century, an idealised notion of motherhood persists. The cinema provides a source of information about attitudes towards mothering in Australian society which is not diminished by the fact that mothers are often marginal to the narrative. While the study recognises that cinematic images are not unconditionally authoritative, it rests on the belief that films have some capacity to reflect and influence society. The films are placed in an historical context with regard to social change in Australian society, so that the images can be understood within the context of the time of the making and viewing of the films. The depictions of the mother are scrutinised with regard to her appearance, her attitude, her relationship with others and the expectations, whether explicit or implicit, of her role. Of particular significance is what happens to her during the film and whether she is punished or rewarded for her behaviour. The conclusions reached after analysis are used to challenge those ideas which assume that portrayals of motherhood are unchangeable and timeless. -

Annual Report 1998-1999

Prepare students and industry pra c t i t i o n e rs to the highest standard fo r wo rk in the fi l m , broadcasting and new media industri e s . E n c o u rage experi m e n t a t i o n , i n n ovation and excellence in screen and broadcasting production. P r ovide national access to education and training programs and resource materi a l s . Foster a close relationship and collaboration with industry. Strengthen an international profi l e. E n c o u rage social and cultural dive rsity among progra m - m a ke rs in the fi l m , broadcasting and new media industri e s . Conduct and encourage research into screen and broadcasting production especially where relevant to education and training issues. Foster a creative, c o l l a b o ra t i ve and productive wo rking env i r o n m e n t attuned to AFTRS educational objective s . P ROFESSIONALISM ■ D I V E R S I T Y EXCELLENCE ■ I N N OVAT I O N C O L L A B O R ATION ■ C R E AT I V I T Y 6 Introduction 7 Council Structure 9 Management Discussion 11 Financial and Staffing Resources Summar y 13 Organisation Chart 14 Report of Operations 15 Objective 1:Preparation for Industry 22 Objective 2:Encouraging Excellence 29 Objective 3: National Access 41 Objective 4: Industry Collaboration 48 Objective 5: International Perspective 56 Objective 6: Social and Cultural Diversity 61 Objective 7: Research and Policy 66 Objective 8: Creative and Productive Environment 80 Appendixes 81 1. -

Download Newsletter 14 for November 2005

WHAT’S THE NEWS? ISSUE 14 NOVEMBER 2005 FRIENDS OF THE NATIONAL FILM AND SOUND ARCHIVE INC Founding Patrons: Gil Brealy, Bryan Brown, Anthony Buckley, Scott Hicks, Patricia Lovell, Chris Noonan, Michael Pate, Fred Schepisi, Albie Thoms ‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.’ Margaret Mead IMPORTANT REMINDER Please take this excellent opportunity to support the essential work of the Friends. It is incredibly easy. Just bring yourself and your friends along to our screening. FRIENDS FILM SCREENING AND ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING The Annual General Meeting of the Friends will be held at Electric Shadows cinema on Sunday 20 November at 7.30pm. We will screen a superb 35mm print (on loan from the US Library of Congress) of a rarely seen film: ABROAD WITH TWO YANKS, directed by Allan Dwan in 1944. The story is set in wartime Sydney but the film was made entirely on a Hollywood backlot, with Americans in all of the Australian roles. It provides a remarkable insight into how Aussies were perceived by the Yanks at this time. Historical interest—and title pun—aside, the film is a real charmer, high-spirited and delightful. William Bendix and Dennis O’Keefe star as two American soldiers on leave who both fall for the same Aussie girl (played by Helen Walker). Their exuberant high jinks and adventures are depicted in a lively and no-nonsense style by Hollywood veteran director, Allan Dwan. The screening will be a fund-raiser for the Friends, and all tickets will be $14 (no concessions). -

The Films of Peter Weir

THE CINEMATIC MYSTICAL GAZE: The films of Peter Weir RICHARD JAMES LEONARD Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2003 Cinema Studies Program School of Fine Arts, Classical Studies and Archaeology The University of Melbourne Abstract Peter Weir is one of Australia’s most critically acclaimed and commercially successful directors. Ever since Weir’s feature film debut with The Cars that Ate Paris in 1974, his work has been explored for unifying themes. Scholars have analysed his films from many perspectives: the establishment of identification and identity especially through binary oppositions in the diegesis;1 the creation of an oneiric atmosphere as a way of exploiting the spectator’s dream experience;2 a clash of value systems;3 the ambiguous nature of narrative structure and character motivations leading to the creation of a sense of wonder;4 the experience of the protagonist placed in a foreign culture wherein conflict arises from social clashes and personal misunderstandings;5 and at the particular ways his films adapt generic codes in service of a discernible ideological agenda.6 To the best of my knowledge there has been no study of the mystical element of Weir’s work in relation to the construction of a cinematic mystical gaze or act of spectatorship. Within a culture defined by its secularity and a national cinema marked by quirky comedies and social realism, almost all of Weir’s films have been described as mystical, arcane or interested in metaphysics. Such an observation could warrant no further investigation if it is held that this critical commentary is but hyperbole in its attempt to grasp what constitutes a Peter Weir film. -

Download Newsletter 21 for July 2009

FRIENDS OF THE NATIONAL FILM AND SOUND ARCHIVE INC NEWSLETTER ISSUE 21 July 2009 Founding Patrons: Gil Brealy, Bryan Brown, Anthony Buckley, Scott Hicks, Patricia Lovell, Chris Noonan, Michael Pate, Fred Schepisi, Albie Thoms Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has. Margaret Mead DEAR FRIENDS, It is nearly a year since the NFSA achieved independent statutory status, on 1 July 2008. This was first recommended in the report of its initial Advisory Committee, Time in our hands, in 1985. You can read the Act at http://tinyurl.com/kj7wzq . With the implementation of the Act, the NFSA’s former association with the Australian Film Commission (merged into Screen Australia as from the same date) has come to an end. Under the Act the NFSA has a governing Board, which took office on the same date. It is chaired by Professor Chris Puplick AM and membership includes the founding president of the Friends of the NFSA, Andrew Pike OAM. In November Dr Darryl McIntyre took up the position of inaugural Chief Executive. For more information about Dr McIntyre, Professor Puplick and the new Board, you can go to the NFSA website: http://www.nfsa.gov.au/about_us/corporate/ceo_profile.html For more background, read on…… THE FRIENDS COMMITTEE At the AGM Friday 16 December 2008, the following committee members were elected: Ann Baylis (President), Sue Terry (Secretary), Chris Emery (Treasurer), Adrian Cunningham, Ray Edmondson, James Sandry, Chris Harrison. Outgoing committee members Shelley Clarke, Peter Hislop, Andrew Pike and Simon Weaving were thanked for their many years of service to the Friends. -

7New South Wales Film and Television Office Annual Report 2006-2007

new south wales film and7 television office annual report 2006-2007 mission to foster and facilitate creative excellence and commercial growth in the film and television industry in new south wales New South Wales Film and Television Office Annual Report 2006-07 1 The New South Wales Film and Television Office is a statutory authority of, and principally funded by, the NSW State Government. New South Wales Film and Television Office Level 13, 227 Elizabeth Street Sydney NSW 2000 Australia Telephone 612 9264 6400 Facsimile 612 9264 4388 Freecall 1300 556 386 Email [email protected] Web www.fto.nsw.gov.au Hours of Business 9.00am–5.30pm Monday – Friday ISSN 1037-0366 Clubland 2 contents Section O1 4 Letter to the Minister 6 Message from the Chair and Chief Executive 8 Members of the Board 10 Organisational Chart (as at 30 June 2007) 12 Charter Section O2 15 Development 17 Project Development 17 Aurora 18 New Feature Film Writers Scheme (NFFWS) 18 Hothouse 18 Market Access and Travel Assistance 18 Industry Liaison 18 Guidelines 19 Young Filmmakers Fund 20 New Media 21 Industry and Audience Development Section O3 25 Investment 26 Production Finance 27 Indigenous Initiatives 27 Cross Platform 27 Production Loan Finance Fund (Revolving Fund) 27 Critical Acclaim Section O4 29 Liaison 30 Production Liaison 30 PDV – Post Production Digital and Visual Effects Sector 3 31 Regional Filming Fund (RFF) 31 Promoting NSW as a Filming Destination 31 Incentives 31 Making NSW More Film Friendly 31 Logistical Support for Filmmakers Section O5 33 Organisation 35 Board 35 Policy 35 Communications 35 Parliamentary Screening Section O6 37 Performance 39 Performance Indicators Section O7 41 Financials 42 Independent Audit Report 44 Financial Statements 57 Agency Statement Section O8 58 Appendices 76 Index Handbag Prada 4 letter to the minister The Hon. -

Newsletter 28

Business Name Newsletter Title NEWSLETTER DATE VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1 Newsletter 28: November 2013 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE—FROM RAY EDMONDSON We’re glad to be announcing in this issue our “Evening with Anthony Buckley” as the first public event under our MOU with the NFSA, and as a pointer to a series of public events in the new year. We’re looking forward to an entertaining and informative encounter with a major figure in the Australian film industry. And we cordially invite all members to come to the AGM. It will be a simple and efficient occasion, immediately preceding our evening event, but an important point to re- view the past year and the direction of the Friends in the future. COMING UP - Monday 9th December 6.30 AGM and a very special event A Conversation with Tony Buckley Film and television producer and founding patron of the Friends, Anthony (Tony) Buckley AM will reminisce and screen excerpts from a personal filmography that covers more that 50 years, almost as long as his diverse connections, formal and informal, with the NFSA itself. The Beatles, the building of the Opera House and one of Peter Weir’s first short films about composer Richard Meale. Join us for the AGM at 6.30, or come at 7.00, for a wonderful introduction to the treasures of the NFSA and your chance to be one of the first Canberrans to use the stunning new Theatrette at the Film and Sound Archive. Beautifully restored to accommodate the very latest technol- ogy and audience comfort yet retaining the unique Art Deco features for which this building is renown! Your invitation is attached! FRIENDS NEWSLETTER Page 2 NEW PATRONS FOR THE FRIENDS Two prominent members of the film community, and long-time supporters of the NFSA, have accepted an invitation to become Patrons of the Friends. -

Religion and the Anzac Legend on Screen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Avondale College: ResearchOnline@Avondale Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale Arts Papers and Journal Articles Faculty of Humanities and Creative Arts 4-2015 Religion and the Anzac Legend on Screen Daniel Reynaud Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/arts_papers Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Military History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Reynaud, D. (2015). Religion and the Anzac legend on screen. St Mark’s Review: A Journal of Christian Thought and Opinion, 231(1), 48-57. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty of Humanities and Creative Arts at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Papers and Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religion and the Anzac legend on screen Daniel Reynaud In The Broken Years, Bill Gammage’s ground-breaking study of the letters and diaries of about a thousand AIF soldiers, he reported that there were ‘three particular omissions, religion, politics, and sex, and of these perhaps the most surprising is religion.’ While noting instances of religious senti- ment and devotion, he argued that ‘the average Australian soldier was not religious,’ dodging compulsory religious services where possible, and ‘dis- trusting’ chaplains, except for a handful of exceptional ones, who despite the respect they earned through their actions, ‘probably … advanced the piety of their flock only incidentally.’1 Gammage is unexceptional in characterising the Anzacs as indifferent to religion. -

Picnic at Hanging Rock Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joan Lindsay | 208 pages | 18 Mar 2013 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099577140 | English | London, United Kingdom Picnic at Hanging Rock PDF Book Rick Chatenever. Don't have an account? Weir with material for a kind of Australian horror-romance that recalls Nathaniel Hawthorne's preoccupation with the spiritual and moral heritage of his own New England landscape. One commonality between all three versions of the story is Mrs. Appleyard, who is disturbingly calm in full mourning dress with her possessions packed. Edith 6 episodes, Joan Lindsay. Download as PDF Printable version. This would place it roughly 3. In all its iterations, Picnic at Hanging Rock's ending is left purposefully ambiguous. Rose Kenton 6 episodes, Markella Kavenagh Fitzhubert 4 episodes, Lee Cormie Jacki Weaver Minnie. Miss Greta McCraw. Feb 18, Radio Listings. Sibylla Budd Mrs. Rate this season Oof, that was Rotten. But is the plot—an eerie re-telling of a tragic event—based on a true story? Best Writing. Jul 11, Full Review…. When she leaps, they disappear — implying that they too were inventions of her mind that die with her. Despite this, the film was a critical success, with American film critic Roger Ebert calling it "a film of haunting mystery and buried sexual hysteria" and remarked that it "employs two of the hallmarks of modern Australian films: beautiful cinematography and stories about the chasm between settlers from Europe and the mysteries of their ancient new home. Picnic at Hanging Rock Writer However, let it be noted that the film is far more about symbolism and atmosphere than anything else, and on that front, it succeeds admirably.