Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

5099943343256.Pdf

Benjamin Britten 1913 –1976 Winter Words Op.52 (Hardy ) 1 At Day-close in November 1.33 2 Midnight on the Great Western (or The Journeying Boy) 4.35 3 Wagtail and Baby (A Satire) 1.59 4 The Little Old Table 1.21 5 The Choirmaster’s Burial (or The Tenor Man’s Story) 3.59 6 Proud Songsters (Thrushes, Finches and Nightingales) 1.00 7 At the Railway Station, Upway (or The Convict and Boy with the Violin) 2.51 8 Before Life and After 3.15 Michelangelo Sonnets Op.22 9 Sonnet XVI: Si come nella penna e nell’inchiostro 1.49 10 Sonnet XXXI: A che piu debb’io mai l’intensa voglia 1.21 11 Sonnet XXX: Veggio co’ bei vostri occhi un dolce lume 3.18 12 Sonnet LV: Tu sa’ ch’io so, signior mie, che tu sai 1.40 13 Sonnet XXXVIII: Rendete a gli occhi miei, o fonte o fiume 1.58 14 Sonnet XXXII: S’un casto amor, s’una pieta superna 1.22 15 Sonnet XXIV: Spirto ben nato, in cui so specchia e vede 4.26 Six Hölderlin Fragments Op.61 16 Menschenbeifall 1.26 17 Die Heimat 2.02 18 Sokrates und Alcibiades 1.55 19 Die Jugend 1.51 20 Hälfte des Lebens 2.23 21 Die Linien des Lebens 2.56 2 Who are these Children? Op.84 (Soutar ) (Four English Songs) 22 No.3 Nightmare 2.52 23 No.6 Slaughter 1.43 24 No.9 Who are these Children? 2.12 25 No. -

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae: Reflections on a Song of Dowland for viola and piano- reflections or variations? Master thesis For obtaining the academic degree Master of Arts of course Solo Performance Viola in Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität Linz Supervised by: Univ.Doz, Dr. M.A. Hans Georg Nicklaus and Mag. Predrag Katanic Linz, April 2019 CONTENT Foreword………………………………………………………………………………..2 CHAPTER 1………………………………...………………………………….……....6 1.1 Benjamin Britten - life, creativity, and the role of the viola in his life……..…..…..6 1.2 Alderburgh Festival……………………………......................................................14 CHAPTER 2…………………………………………………………………………...19 John Dowland and his Lachrymae……………………………….…………………….19 CHAPTER 3. The Lachrymae of Benjamin Britten.……..……………………………25 3.1 Lachrymae and Nocturnal……………………………………………………….....25 3.2 Structure of Lachrymae…………………………………………………………....28 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………..39 Bibliography……………………………………….......................................................43 Affidavit………………………………………………………………………………..45 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………....46 1 FOREWORD The oeuvre of the great English composer Benjamin Britten belongs to one of the most sig- nificant pages of the history of 20th-century music. In Europe, performers and the general public alike continue to exhibit a steady interest in the composer decades after his death. Even now, the heritage of the master has great repertoire potential given that the number of his written works is on par with composers such as S. Prokofiev, F. Poulenc, D. Shostako- vich, etc. The significance of this figure for researchers including D. Mitchell, C. Palmer, F. Rupprecht, A. Whittall, F. Reed, L. Walker, N. Abels and others, who continue to turn to various areas of his work, is not exhausted. Britten nature as a composer was determined by two main constants: poetry and music. In- deed, his art is inextricably linked with the word. -

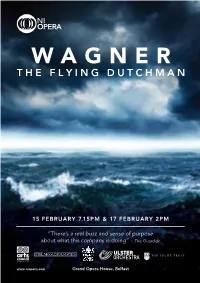

There's a Real Buzz and Sense of Purpose About What This Company Is Doing

15 FEBRUARY 7.15PM & 17 FEBRUARY 2PM “There’s a real buzz and sense of purpose about what this company is doing” ~ The Guardian www.niopera.com Grand Opera House, Belfast Welcome to The Grand Opera House for this new production of The Flying Dutchman. This is, by some way, NI Opera’s biggest production to date. Our very first opera (Menotti’s The Medium, coincidentally staged two years ago this month) utilised just five singers and a chamber band, and to go from this to a grand opera demanding 50 singers and a full symphony orchestra in such a short space of time indicates impressive progress. Similarly, our performances of Noye’s Fludde at the Beijing Music Festival in October, and our recent Irish Times Theatre Award nominations for The Turn of the Screw, demonstrate that our focus on bringing high quality, innovative opera to the widest possible audience continues to bear fruit. It feels appropriate for us to be staging our first Wagner opera in the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, but this production marks more than just a historical anniversary. Unsurprisingly, given the cost and complexities involved in performing Wagner, this will be the first fully staged Dutchman to be seen in Northern Ireland for generations. More unexpectedly, perhaps, this is the first ever new production of a Wagner opera by a Northern Irish company. Northern Ireland features heavily in this production. The opera begins and ends with ships and the sea, and it does not take too much imagination to link this back to Belfast’s industrial heritage and the recent Titanic commemorations. -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN's USE of the Passacagt.IA Bernadette De Vilxiers a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Wi

BENJAMIN BRITTEN'S USE OF THE PASSACAGt.IA Bernadette de VilXiers A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Johannesburg 1985 ABSTRACT Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) was perhaps the most prolific cooposer of passaca'?' las in the twentieth century. Die present study of his use of tli? passac^.gl ta font is based on thirteen selected -assacaalias which span hin ire rryi:ivc career and include all genre* of his music. The passacaglia? *r- occur i*' the follovxnc works: - Piano Concerto, Op. 13, III - Violin Concerto, Op. 15, III - "Dirge" from Serenade, op. 31 - Peter Grimes, Op. 33, Interlude IV - "Death, be not proud!1' from The Holy Sonnets o f John Donne, Op. 35 - The Rape o f Lucretia, op. 37, n , ii - Albert Herring, Op. 39, III, Threnody - Billy Budd, op. 50, I, iii - The Turn o f the Screw, op . 54, II, viii - Noye '8 Fludde, O p . 59, Storm - "Agnu Dei" from War Requiem, Op. 66 - Syrrvhony forCello and Orchestra, Op. 68, IV - String Quartet no. 3, Op. 94, V The analysis includes a detailed investigation into the type of ostinato themes used, namely their structure (lengUi, contour, characteristic intervals, tonal centre, metre, rhythm, use of sequence, derivation hod of handling the ostinato (variations in length, tone colouJ -< <>e register, ten$>o, degree of audibility) as well as the influence of the ostinato theme on the conqposition as a whole (effect on length, sectionalization). The accompaniment material is then brought under scrutiny b^th from the point of view of its type (thematic, motivic, unrelated counterpoints) and its importance within the overall frarework of the passacaglia. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge. -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN a Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST

BENJAMIN BRITTEN A Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST Choir of Clare College, Cambridge Graham Ross FRANZ LISZT A Ceremony of Carols BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) ANONYMOUS, arr. BENJAMIN BRITTEN 1 | Venite exultemus Domino 4’11 12 | The Holly and the Ivy 3’36 for mixed choir and organ (1961) traditional folksong, arranged for mixed choir a cappella (1957) 2 | Te Deum in C 7’40 for mixed choir and organ (1934) BENJAMIN BRITTEN 3 | Jubilate Deo in C 2’30 13 | Sweet was the song the Virgin sung 2’45 for mixed choir and organ (1961) from Christ’s Nativity for soprano and mixed choir a cappella (1931) 4 | Deus in adjutorium meum intende 4’37 from This Way to the Tomb for mixed choir a cappella (1944-45) A Ceremony of Carols op. 28 (1942, rev. 1943) version for mixed choir and harp arranged by JULIUS HARRISON (1885-1963) 5 | A Hymn to the Virgin 3’23 for solo SATB and mixed choir a cappella (1930, rev. 1934) 14 | 1. Procession 1’18 6 | A Hymn of St Columba 2’01 15 | 2. Wolcum Yole! 1’21 for mixed choir and organ (1962) 16 | 3. There is no rose 2’27 7 | Hymn to St Peter op. 56a 5’57 17 | 4a. That yongë child 1’50 for mixed choir and organ (1955) 18 | 4b. Balulalow 1’18 19 | 5. As dew in Aprille 0’56 JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) 20 | 6. This little babe 1’24 8 | The Holy Boy 2’50 version for mixed choir a cappella (1941) 21 | 7. -

Concert: Opera Workshop: the Music of Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 12-12-2019 Concert: Opera Workshop: The Music of Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Christopher Zemliauskas Dawn Pierce Opera Workshop Students Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zemliauskas, Christopher; Pierce, Dawn; and Opera Workshop Students, "Concert: Opera Workshop: The Music of Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)" (2019). All Concert & Recital Programs. 6299. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/6299 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Opera Workshop: The Music of Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Christopher Zemliauskas, music director Dawn Pierce, director Blaise Bryski, accompanist/coach Nicolas Guerrero, accompanist/coach Hockett Family Recital Hall Thursday, December 12th, 2019 6:30 pm Program The Rape of Lucretia (1946), Act I, scene 2 Lindsey Weissman, contralto - Lucretia Sarah Aliperti, mezzo soprano - Bianca Olivia Schectman, soprano - Lucia Andrew Sprague, baritone - Tarquinius Catherine Kondi, soprano - Female Chorus Lucas Hickman, tenor - Male Chorus The Turn of the Screw (1954), Act I Isabel Vigliotti, soprano - Flora Catherine Kondi, soprano - Governess The Rape of Lucretia (1946), Act II, scene 1 Lindsey Weissman, contralto - Lucretia -

Download Booklet

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The artists are grateful for the sponsorship consideration of the following individuals and organiza- tions: Karen Vickers in memory of John E. Vickers and Velma Schuman Oglesby, Michael Wolf in memory SONGS OF JUDITH WEIR, BENJAMIN BRITTEN & HAMISH MACCUNN of Clarice Theisen, Mark and Donna Hance, Nan and Raleigh Klein, Steve and Mary Wolf, Tim and Amanda Orth, Martha and Emil Cook, Brett Cook, Megan Clodi in memory of Eric McMillan, Steve Stapleton, CALEDONIAN SCENES Nathan Munson, Sherri Phelps and Ronaldus Van Uden, Jennifer Fair, Lucy Walker, Tony Solitro, Zachary Justin Vickers, tenor Geoffrey Duce & Gretchen Church, piano Wadsworth, Robert and Margaret Lane, Ian Hamilton in memory of John Hamilton, Anthony and Maria Moore, Carren Moham, Melissa Johnson, Joy Doran in memory of Steve Doran, Jonathan Schaar in memory of organist John Weissrock, Jerold Siena and Stasia Forsythe Siena in memory of William J. Forsythe, James Major in memory of Bettie Major, Roy Magnuson, Michele Robillard Raupp, Eric Saylor, Christopher Scheer, Brooks Kuykendall, Thornton Miller, Andrew Luke, Emily Vigneri, Hilary Donaldson, Imani Mosley, Annie Ingersoll and Eric Totte, and Jeanne Wilson and Gary Stoodley; research funds from the School of Music and the Wonsook Kim College of Fine Arts at Illinois State University; a grant from the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs at Illinois State University; an Illinois Arts Council Grant; research funds from Illinois Wesleyan University; and a PSC-CUNY Grant from City University of New York. The MacCunn songs and the cycle on this disc may be found in Hamish MacCunn: Complete Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, Parts 1 and 2 (A-R Editions, 2016), edited by Jennifer Oates. -

Britten's Acoustic Miracles in Noye's Fludde and Curlew River

Britten’s Acoustic Miracles in Noye’s Fludde and Curlew River A thesis submitted by Cole D. Swanson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2017 Advisor: Alessandra Campana Readers: Joseph Auner Philip Rupprecht ii ABSTRACT Benjamin Britten sought to engage the English musical public through the creation of new theatrical genres that renewed, rather than simply reused, historical frameworks and religious gestures. I argue that Britten’s process in creating these genres and their representative works denotes an operation of theatrical and musical “re-enchantment,” returning spiritual and aesthetic resonance to the cultural relics of a shared British heritage. My study focuses particularly on how this process of renewal further enabled Britten to engage with the state of amateur and communal music participation in post-war England. His new, genre-bending works that I engage with represent conscious attempts to provide greater opportunities for amateur performance, as well cultivating sonically and thematically inclusive sound worlds. As such, Noye’s Fludde (1958) was designed as a means to revive the musical past while immersing the Aldeburgh Festival community in present musical performance through Anglican hymn singing. Curlew River (1964) stages a cultural encounter between the medieval past and the Japanese Nō theatre tradition, creating an atmosphere of sensory ritual that encourages sustained and empathetic listening. To explore these genre-bending works, this thesis considers how these musical and theatrical gestures to the past are reactions to the post-war revivalist environment as well as expressions of Britten’s own musical ethics and frustrations.