Young Jewish American Composers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, launch May 1 with an event at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York completion of this landmark project in December 2021. Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed rare or unique books have now been digitized and put Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah online for researchers, teachers, and students around the photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article world to read. The next important step in developing (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to European Jewish Life. The museum will launch early explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures 2021. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, is currently being tested. Through Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us the art of storytelling the museum will provide the online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). historical context for the archive’s vast array of original documents, books, and other artifacts, with some materials being translated to English for the first time. -

First Glimpse 2018: Songs from the Great Room

presents First Glimpse 2018: Songs from the Great Room World Premiere Songs rom e 17-19 omosers e oie series Composers & the Voice Artistic Director - Steven Osgood Musical Direction by Mila Henry & Kelly Horsted 2017-19 Composers & the Voice Composer and Librettist Fellows Laura Barati Pamela Stein Lynde Sokunthary Svay Matthew Browne Scott Ordway Amber Vistein Kimberly Davies Frances Pollock Alex Weiser 2017-18 Composers & the Voice Resident Singers Tookah Sapper, soprano Jennifer Goode Cooper, soprano Blythe Gaissert, mezzo-soprano* Blake Friedman, tenor Mario Diaz Moresco, baritone Adrian Rosas, bass-baritone *Songs written for mezzo-soprano will be performed tonight by Kate Maroney Resident Stage Manager - W. Wilson Jones May 19 & 20, 2018 - 7:30 PM SOUTH OXFORD SPACE, BROOKLYN FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR I always have mixed emotions when a cycle of Composers and the Voice arrives at the First Glimpse concerts. It is thrilling to FINALLY throw open the doors of this room and share some of the wonderful pieces that have been written since last Fall. But it also means that my time working so regularly and directly with a family of artists is drawing to a close. It takes a huge team of people to make a program like Composers and the Voice work, but I would like to thank two who have stepped into new and significantly larger roles this year. Mila Henry, C&V Head of Music, has overseen the musical organization of the entire season, while also preparing several pieces for each of our workshop sessions. Matt Gray, as C&V Head of Drama, has brought his insight into character and operatic narrative into every element of the program. -

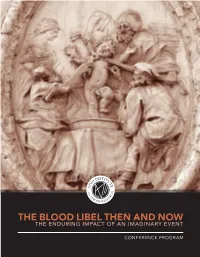

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

River to River

RIVER TO RIVER June 19–29 Photo credit: George Kontos RiverToRiverNYC.com Get Social: #R2R2014 Follow us on Twitter @R2RFestival Like us on Facebook/RiverToRiver Share photos with us on Instagram @R2RFestival Subscribe to our email newsletter to receive updates, insider tips, and volunteer opportunities. Supporting LMCC is one of the best ways to stay connected to Lower Manhattan’s vibrant cultural future. Donate online and learn more about the benefits of joining LMCC’s diverse network of supporters at LMCC.net/support RiveR To RiveR 2014 June 19–29 11 days, 35 projects, 90+ artists All events are free and in Lower Manhattan. River To River inspires residents, workers, and visitors in the neighborhoods south of Chambers Street by connecting them to the creative process, unique places, and each other in order to demonstrate the role that artists play in creating vibrant, sustainable communities. Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) has been the lead producer and curator of River To River since 2011. LMCC empowers artists by providing them with networks, resources, and support, to create vibrant, sustainable communities in Lower Manhattan and beyond. Whether you see the work of one, two, or 20 artists, we hope that you’ll remember your experience and enjoy getting closer to the transformative work of artists and discovering something that you didn’t know or hadn’t seen before. In addition to the River To River performances, installations, talks, digital journeys, and open studios, there are plenty of opportunities to hang out with artists, partners, audiences, and staff in a casual setting. A little like themed “house parties” that feature pop-up performances and DJ sets, the R2R Living Rooms provide an ideal setting to unwind, eat, drink, and dance it out after a day out on the town, soaking in the art. -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Program Features Don Byron's Spin for Violin and Piano Commissioned by the Mckim Fund in the Library of Congress

Concert on LOCation The Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress "" .f~~°<\f /f"^ TI—IT A TT^v rir^'irnr "ir i I O M QUARTET URI CAINE TRIO Saturday, April 24, 2010 Saturday, May 8, 2010 Saturday, May 22, 2010 8 o'clock in the evening Atlas Performing Arts Center 1333 H Street, NE In 1925 ELIZABETH SPRAGUE COOLIDGE established the foundation bearing her name in the Library of Congress for the promotion and advancement of chamber music through commissions, public concerts, and festivals; to purchase music manuscripts; and to support musical scholarship. With an additional gift, Mrs. Coolidge financed the construction of the Coolidge Auditorium which has become world famous for its magnificent acoustics and for the caliber of artists and ensembles who have played there. The McKiM FUND in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson, to support the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. The audiovisual recording equipment in the Coolidge Auditorium was endowed in part by the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress. Request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 [email protected]. Due to the Library's security procedures, patrons are strongly urged to arrive thirty min- utes before the start of the concert. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the chamber music con- certs. -

PDF Transition

! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:” ! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN PERICH! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation! Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School! of Cornell University! in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of! Doctor of Musical! Arts! ! ! by! David Benjamin Friend! May 2019! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © 2019 David Benjamin! Friend! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:”! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN! PERICH! ! David Benjamin Friend, D.M.A.! Cornell University,! 2019! ! !This dissertation examines the life and work of Tristan Perich, with a focus on his works for keyboard instruments. Developing an understanding of his creative practices and a familiarity with his aesthetic entails both a review of his personal narrative as well as its intersection with relevant musical, cultural, technological, and generational discourses. This study examines relevant groupings in music, art, and technology articulated to Perich and his body of work including dorkbot and the New Music Community, a term established to describe the generationally-inflected structural shifts! in the field of contemporary music that emerged in New York City in the first several years of the twenty-first century. Perich’s one-bit electronics practice is explored, and its impact on his musical and artistic work is traced across multiple disciplines and a number of aesthetic, theoretical, and technical parameters. This dissertation also substantiates the centrality of the piano to Perich’s compositional process and to his broader aesthetic cosmology. A selection of his works for keyboard instruments are analyzed, and his unique approach to keyboard technique is contextualized in relation to traditional Minimalist piano techniques and his one-bit electronics practice." ! ! BIOGRAPHICAL! SKETCH! ! !! !David Friend (b. -

Orchestration and Melodic Doublings: an Analysis and Comparison Between Samuel Adler and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov’S Approach Austin Simonds MUCP 4320

Orchestration and Melodic Doublings: An Analysis and Comparison between Samuel Adler and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov’s Approach Austin Simonds MUCP 4320 Abstract How do the viewpoints and approaches of Samuel Adler (The Study of Orchestration) and Rimsky-Korsakov (Principles of Orchestration) differ regarding melodic doublings? And if so, does this effect musical style or practice? These two textbooks are, and continue to be, the standard for courses and other pedagogical approaches with the art of composition. I will compare and contrast the two, as well as analyze the melodic doublings found in Sergei Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto, in an attempt to discover if either of the two texts fit a certain musical style over others. Composition has been understood as the mastery of harmony, counterpoint, and form. Only recently, within the last couple hundred years or so has orchestration slowly risen and developed into a separate art itself. Orchestration is defined as the study of writing for orchestra.1 Like the other pillars of composition, orchestration is a discipline that can be taught and mastered through study and practice. The two texts I have selected to compare were chosen based on their popularity in this subject, as well as the attention these specific texts receive for teaching this material. I will be looking at correlations between the two and analyze the melodic doublings found in Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto to find any possible relation between the treatises and musical style. To fully analyze and understand the differences between the two treatises, it is imperative to study not only the text, but also the authors themselves. -

Guest Artist Series:Kesatuan Duo

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 10-6-1999 Guest Artist Series:Kesatuan Duo Karen DeWig Flute Illinois State University Ingrid Gordan Marimba Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation DeWig, Karen Flute and Gordan, Ingrid Marimba, "Guest Artist Series:Kesatuan Duo" (1999). School of Music Programs. 1898. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/1898 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Music Department I Illinois State University I I I Guest Artist Series I Kesatuan Duo Karen DeWig, flute I Ingrid Gordan, marimba I I I I Kemp Recital Hall Wednesday Evening I October 6, 1999 8:00 p.m. I The Eleventh Program of the 1999-2000 Season. I 1· I Program Program Notes I I Ingrid Grete Gordon made her debut as a marimba soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at age 18. In 1988 she first appeared Figures in a Landscape (1984) Peter Klatzow as a solo percussion recitalist in the Young Steinway concert series, (born 1945) and has performed in numerous recital and .concert series since then. I I . Ms. Gordon is currently completing a Doctor of Musical Arts degree Double Labyrinth (1998) Mikel Kuehn in percussion at the University of Illinois. -

Lori Goldston Lorigoldston.Com | +1 206.715.4540| [email protected]

Lori Goldston lorigoldston.com | +1 206.715.4540| [email protected] Selected Commissioned Works Death and the Mourning After for Timothy White Eagle Improvised solo acoustic cello score for an livestreamed theater performance, part of La MaMa’s Reflections of Native Voices Festival. 2021 Manzanar, Diverted Composed a score for a feature-length documentary by Ann Kaneko, in collaboration with Steve Fisk, Alexander Mirana, Susie Kozawa and Matt Chamberlain. 2021 What You Can Hear From Here for Art Saves Me Commissioned by One Reel to create new work for an online exhibition. In collaboration with videographer Isaac Hanson. Seattle. 2020 Rivulet, for Nonsequitur Composed and performed an evening-length piece for a small ensemble; with Greg Kelley, Kole Galbraith, Dave Abramson and Haley Freedlund. Chapel Performance Space, Seattle. 2019 Yellowstone, for Jon Jost Recorded an improvised solo amplified cello score for a work-in-progress video installation. Featured as part of Nonsequitur’s “Wayward In Limbo”. Seattle. 2019 Ama (The Woman Diver), for Nalanda West Performed an improvised solo acoustic cello score for Jim Fletcher and Katiana Rangel’s production of a 14th Century Japanese play. Seattle. 2018 Études N°11, for Paris Fashion Week Composed and performed a solo acoustic cello score accompanying the runway show for fashion house Études. Paris, France. 2017 That Sunrise, for the BBC Scottish Symphony Composed and performed a new work for amplified cello and orchestra as part of Glasgow Tectonics Festival. Glasgow. 2017 The Seawall , for the City of Seattle With drummer Dan Sasaki, composed and recorded a response to Seattle’s seawall reconstruction project. -

Sing, Sing Ye Muses Sing

ClaraClara Longstreth, Longstreth, Music Music Director Director ClaraClara Longstreth, Longstreth, Music Music Director Director Sing,Sing, Sing Sing Ye Ye Muses Muses ChoralChoral Classics Classics and and a aPremiere Premiere U UPCOMINGPCOMING C CONCERTSONCERTS HymnHymn to to the the Dawn Dawn SongsSongs of Serenityof Serenity and and Joy Joy BroadwayBroadway Presbyterian Presbyterian Church Church BroadwayBroadway at 114that 114th Street Street Friday,Friday, March March 9, 9,2018 2018 at 8:00pmat 8:00pm TheThe Church Church of theof the Holy Holy Trinity Trinity 315315 East East 88th 88th Street Street Sunday,Sunday, March March 11, 11, 2018 2018 at 4:00pmat 4:00pm RejoiceRejoice in in the the Lamb Lamb A CenturyA Century of Choralof Choral Favorites Favorites St.St. Ignatius Ignatius of Antiochof Antioch Episcopal Episcopal Church Church 554554 West West End End Avenue Avenue Wednesday,Wednesday, May May 30, 30, 2018 2018 at 8:00pmat 8:00pm New Amsterdam Singers Advent Lutheran Church Broadway at West 93rd Street, New York City Friday, December 8, 2017 at 8 pm Sunday, December 10, 2017 at 4 pm Clara Longstreth, Music Director David Recca, Assistant Conductor Nathaniel Granor, Chamber Chorus Assistant Conductor Pen Ying Fang, Accompanist Jude Ziliak, Anna Luce, violins Scot Moore, viola Oliver Weston, cello HANK YOU for joining us as we begin the 50th season of New Amsterdam Singers. This anniversary is a major milestone by any Sing, Sing, Ye Muses John Blow (1649-1708) T Chorus, violins and continuo standard, but in our case it is particularly remarkable because all 50 (please hold applause) years have been under the inspired leadership of our founding Music Duo Seraphim Jacob Handl (1550-1591) Double Chorus Director, Clara Longstreth. -

2012 Program Guide

"# && # " $ % $ " " " !' TD Sponsor.indd 1 4/17/12 2:36:06 PM .0& ,&, 22 ',0 .0& )()//&0 #-% 1 #-% ,&, 22', && 33" #% 1 #% !& 3# - )() % 1 % & -* - , 33" $1$ 01091705.ad 1 4/23/12 9:00:16 AM Welcome to the 27th Annual TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival @ek_\nfi[jf]aXqqdlj`Z`Xe?\iY`\?XeZfZb1Èdlj`Z`jXeXik]fidk_Xk kiXejZ\e[jcXe^lX^\%É@ek_Xkjg`i`k#K;9Xeb>iflg`jgc\Xj\[kfYi`e^pfl# ]fik_\k\ek_Zfej\Zlk`m\p\Xi#k_\)'()K;MXeZflm\i@ek\ieXk`feXcAXqq =\jk`mXc#Xe\m\ekk_XkZ\c\YiXk\jk_\[`m\ij`kpXe[\ek\ikX`ed\ekf]dlj`ZYp kXc\ek\[Xik`jkj]ifd:XeX[XXe[Xifle[k_\nfic[% K;jki`m\jkf\e_XeZ\k_\Zfddle`k`\j`en_`Z_n\j\im\#Xe[n_XkY\kk\i nXpkfYi`e^g\fgc\kf^\k_\ik_Xekfj_Xi\`ek_\cfm\f]^i\Xkdlj`ZK_XkËj n_pK;`jgifl[kfjgfejfik\edXafidlj`Z]\jk`mXcj]ifdM`Zkfi`Xkf?Xc`]Xo% >i\Xk]\jk`mXcj[feËk_Xgg\en`k_flk^i\Xkg\fgc\kffi^Xe`q\Xe[ilek_\d%N\Ë[c`b\kfk_Xeb \m\ipfe\n_f`j`emfcm\[n`k_dXb`e^k_\)'()K;MXeZflm\i@ek\ieXk`feXcAXqq=\jk`mXcX_`k Æ]ifdmfclek\\ijXe[fi^Xe`q\ij#kfk_\kXc\ek\[]\Xkli\[Xik`jkjXe[k_fljXe[jf]dlj`Zcfm\ij n_faf`elj\m\ipp\Xi%PflijlggfikdXb\jk_`j`eZi\[`Yc\\m\ekgfjj`Yc\% =fik_\cfm\f]dlj`Z#k_Xebpfl% AXe\Iljj\cc J\e`fiM`Z\Gi\j`[\ek#GXZ`ÔZI\^`fe 8D<JJ8><=IFDK?<:F8JK8CA8QQ9CL<JJF:@<KP 9:ËjcXi^\jkdlj`Zgi\j\ek\i#:fXjkXcAXqq`j MXeZflm\i8ik>Xcc\ip]fik_\`ijlggfik`e n\ccbefne]fi`kj[Xi`e^Xik`jk`Zm`j`fek_Xk _\cg`e^ljdXb\k_`jdfm\% Z\c\YiXk\j`eefmXk`fe#[`m\ij`kpXe[`eZclj`m`kp K_\]\jk`mXcËjjk\ccXic`e\lgY\^`ejn`k_X `edlj`Z#n`k_`eXm`YiXekXe[\m\i$\mfcm`e^ i`^_k\fljE\nFic\XejY`cc]\Xkli`e^k_\