Tjmversily Microfilms International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

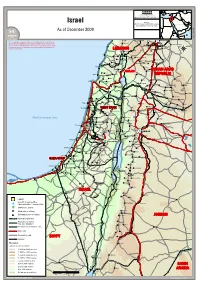

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

ISRAEL 15 Study Visit What Will It Take to Leap Israel's Social and Economic Performance? Mon-Thu, June 8 – June 11, 2009

1 March 2009 ISRAEL 15 Study Visit What Will It Take to Leap Israel's Social and Economic Performance? Mon-Thu, June 8 – June 11, 2009 The ISRAEL 15 Vision The ISRAEL 15 Vision aims to place Israel among the fifteen leading countries in terms of quality of life. This vision requires a 'leapfrog' from our present state of development i.e. a significant and continuous improvement in Israel's social and economic performance in comparison to other countries. Our Study Visit will focus on this vision and challenge. The ISRAEL 15 Agenda and Strategy There is no recipe for leapfrogging; it is the result of a virtuous alignment in economic policy, powerful global trends and national leadership. Few countries have leapt including Ireland, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Chile, and Israel (between the 50s- 70s). The common denominator among these countries has been their agenda. They focused on: developing a rich and textured vision; exhausting engines of growth; tapping into unique advantages; improving the capacity for taking decisions and implementing them; benchmarking with other countries; and turning development and growth into a national obsession. Furthermore, leapfrogging requires a top-down process driven by the government, as well as a bottom-up mobilization of the key sectors of society such as mayors and municipal governments, business leaders, nonprofits, philanthropists, career public servants and, in Israel's case, also the world Jewry. The Study Visit will explore this agenda as it applies to Israel. The Second ISRAEL 15 Conference; Monday, June 8, 2009 The Second ISRAEL 15 Conference titled: "Effectuating the Vision Now!" will be held on Monday, June 8th. -

BUS ROUTE Hiking TRAILS in Sde Boker Area

INDEX ACCOMMODATIONS BUS ROUTE HIKING TRAILS IN SDE BOKER AREA Bus Station Point of Interest DORM / NAME OF NAME TYPE PHONE FACILITIES WEBSITE BEER SHEVA DBL BUS STOP T P el Av iv 64/65 Main Road Suggested Hike "Mashabim" Yeruham Country Lodging 08-6565134/6 NA / 500 ILS www.mashabim.co.il Mashabei Sade (Kibutz) 40 204 country Lodging 40 60/64 1 Sfinat Hamidbar 08-655718 Trail Gas station Bedouin Tent 75 / 225 ILS www.sfinat-hamidbar.com Mashabim P kibbutz Sde boker 2 (Desert ship) 052-3900020 64/65 Haroaa 4x4 Road Parking Lot Campground Free Tzrif Ben Gurion 3 Campground Ramat Hovav 60/64 Forest / Thicket Shopping Center Silent Arrow Camp Lodge 052-6611561 80 / 250 ILS www.silentarrow.co.il Merkaz Tapuah Midreshet Ben Gurion 4 64/65 Har Nanegev Youth Hostel 08-6588615/16 392 - 458 ILS www.teva.co.il Nahal Sirpad / Har Gamal Accommodation ATM 5 Field School The Green www. Hostel 08-6532319 85 / 285 ILS Nahal Sirpad / Har Gamal Backpackers thegreenbackpackers.com Dining Public Toilet 6 60/65 P Smart Hotels Hotel 08-6588884 530 - 670 ILS www.ramonhotel.com Nahal Arod / Nahal Meishar Ramon 224 7 Ein Avdat DRIVING TIME Mitzpe Ramon HANEGEV entrance Youth hostel 02-5945712 140 / 380 ILS www.iyha.org.il Nahal Ha-Ella / Nahal Tzin JUNCTION P P 8 Youth Hostel Mitzpe Ramon 2 22 Desert Wind Hostel 050-5903661 80 / 250 ILS www.desert-guest-tent.co.il Merkaz Mishari 222 9 21 00:35 Avdat Ruins Desert Shade Camp Lodge 054-6277413 70 - 270 ILS www.desert-shade.com Merkaz Mishari 10 Kibbutz Mashabei Sade 00:45 00:45 Ben Gurion Collage/Ein Avdat TLALIM 1 * Prices: dorm bed (1 person) / private double room (2 people). -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Visitors Information

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Visitors Information Contact information Beer-Sheva | Marcus Family Campus Aya Bar-Hadas, Head, Visitors Unit, Dana Chokroon, Visits Coordinator, Office: 972-8-646-1750 Office: 972-8-642-8660 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Cell: 972-52-579-3048 Cell: 972-52-879-5885 [email protected] [email protected] Efrat Borenshtain, Visits Coordinator, Hadas Moshe Bar-hat , Visits Coordinator, Office: 972-8-647-7671 Office: 972-8-646-1280 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Fax: 972-8-647-2865 Cell: 972-50-202-9754 Cell: 972-50-686-3505 [email protected] [email protected] • When calling Israel from abroad dial: Exit code + 972 + x-xxx-xxxx o Example if call from a US number: 011-972-8-646-1750. • When calling from within Israel, replace the (972) with a zero. o Example: 08-646-1750. Directions To the Marcus Family Campus By train Take the train to Beer Sheva. Disembark the train at “Beer-Sheva North/University” station (this is the first of two stops in Beer-Sheva). Upon exiting the station, turn right onto the “Mexico Bridge” which leads to the Marcus Family Campus. (For on campus directions see map below). The train journey takes about 55 minutes (from Tel Aviv). For the train schedule, visit Israel Railways website: http://www.rail.co.il/EN/Pages/HomePage.aspx By car For directions, click here From Tel-Aviv (the journey should take about 1 hour 30 minutes, depending on traffic) If using WAZE to direct you to the Campus, enter the address as: Professor Khayim Khanani Street, Be'er Sheva. -

Jnf Blueprint Negev: 2009 Campaign Update

JNF BLUEPRINT NEGEV: 2009 CAMPAIGN UPDATE In the few years since its launch, great strides have been made in JNF’s Blueprint Negev campaign, an initiative to develop the Negev Desert in a sustainable manner and make it home to the next generation of Israel’s residents. In Be’er Sheva: More than $30 million has already been invested in a city that dates back to the time of Abraham. For years Be’er Sheva was an economically depressed and forgotten city. Enough of a difference has been made to date that private developers have taken notice and begun to invest their own money. New apartment buildings have risen, with terraces facing the riverbed that in the past would have looked away. A slew of single family homes have sprung up, and more are planned. Attracted by the River Walk, the biggest mall in Israel and the first “green” one in the country is Be’er Sheva River Park being built by The Lahav Group, a private enterprise, and will contribute to the city’s communal life and all segments of the population. The old Turkish city is undergoing a renaissance, with gaslights flanking the refurbished cobblestone streets and new restaurants, galleries and stores opening. This year, the municipality of Be’er Sheva is investing millions of dollars to renovate the Old City streets and support weekly cultural events and activities. And the Israeli government just announced nearly $40 million to the River Park over the next seven years. Serious headway has been made on the 1,700-acre Be’er Sheva River Park, a central park and waterfront district that is already transforming the city. -

No. 58, December 12, 1974

WfJRKERS IIIIN'(JIIRIJ 2S¢ No.58 ,·afJ;~~' X·523 6 December 1974 300 ,000 Auto Layoffs in December • • • conom rum In DECEMBER I-Auto's Big Four, giant oline) generally. This has cut real industrial-financial monopolies at the wages by over 5 percent in the past heart of the American economy, will year. Profits in capital goods indus layoff close to 300,000 workers this tries such as steel, the most viable Government Threats in Coal Talks month. Production schedules are now "ector of the economy outside of en being drastically cut in light of dismal e .. :.y industries, have been artificially profit reports and continued declining exab'~;er<1.ted both by inflation and re sales. Although the current layoffs are cent ne'arL':ng in anticipation of the supposedly for December only it is ob coal strike. Tn reality orders have flat vious that long-term "adjustments" are tened out thL;, year, and cutbacks will UMW Ranks Resist in order. Ford Motor Company is al soon be required in these areas as well. ready projecting permanent job losses Since President Ford suddenly "dis affecting at least 31,000 workers. Since covered" he recession last month his a layoff in auto means about one and economic ldvisors ar'e now admitting one half layoffs in related sectors that it has been in process already Miller Sellout (rubber, safety glass, etc.) Ford's lat for ten (!) months. In announcing his est cut b a c k s will ultimately put discovery of an economic slump, Sec about 78,000 workers on the streets. -

Memories for a Lifetime

INCLUDED HIGHLIGHTS • An Intimate Group Experience with the Finest Guides and Drivers- Israel’s BEST! • Travel on Luxury Motor Coaches Proudly recognized as one of Israel’s Leading Tour Operators since 1980 • Exciting Comprehensive Itinerary covering the whole country from North to South MEMORIES FOR A LIFETIME Wendy Morse • Deluxe 5 Star Hotels in great locations • ALL spectacular buffet breakfasts • ALL dinners (except two) • Wonderful Evening Entertainment • ALL Entrance Fees – no waiting- the Margaret Morse Group with VIP access • Special Shehecheyanu Welcome in Jerusalem • Group Photograph in Jerusalem Robyn Morse O’Keefe Michael Morse • Gratuities to maids, waiters, and porters throughout the tour • PLUS WONDERFUL SURPRISE EXTRAS ALWAYS !!!! Margaret Morse Tours, Inc. 900 N. Federal Highway, Suite 206 No One Does Israel Better! No One. Hallandale Beach, FL 33009 TEL. 954.458.2021 • FAX. 954.455.9144 Toll Free 1.800.327.3191 Our Tour Guides email: [email protected] For more info visit our Website: www.margaretmorsetours.com Haifa Jerusalem Massada Eilat Tel Aviv www.margaretmorsetours.com 800.327.3191 Margaret Morse Tours, Inc. act only as Agents for various companies, owners, or contractors providing means of transportation, accommodation and other services. All exchange orders, coupons and tickets are issued subject to the terms and conditions under which such means of transportation; accommodations and other services are provided. The issuance and acceptance of such tickets shall be deemed to be consent to the further conditions that Margaret Morse Tours, Inc. shall not be in any way liable for injury, damage, loss, accident, delay or irregularity which may be occasioned either by defect or irregularity in any vehicle, or through the acts or defaults of any company or person engaged in conveying the passengers of any hotel proprietor, personnel or servant otherwise in connection therewith. -

18607 Ventura Blvd Suite 306 Tarzana, Ca 91356 818-342

COMPANIES_NAME ADDRESS CSZ PHONE ` 18607 VENTURA BLVD SUITE 306 TARZANA, CA 91356 818-342-2629 1ST DENVER TITLE 8480 E ORCHARD RD #5700 GREENWOOD VILLAGE, CO 80111 720-482-1411 1ST NATIONAL TITLE 9488 UNION SQUARE SANDY, UT 84070 801-208-0025 1ST NATIONAL TITLE 11576 SOUTH STATE STREET DRAPER, UT 84020 801-676-1940 1ST NATIONAL TITLE INSURANCE AGENCY LLC 460 EAST 1000 NORTH NORTH SALT LAKE UT 84054 801-335-0550 1ST OPTION ESCROW, INC. 724 N. BARRANCA AVE., #A COVINA, CA 91723 626-869-0405 1ST POINT SETTLEMENT, LLC 8 BRILLIANT AVE STE 5 PITTSBURGH, PA 15215 412-781-1643 1ST QUALITY TITLE, LLC 3227 MARICAMP ROAD #101 34480 352-690-1787 1ST SIGNATURE SETTLEMENT SERVICES, LLC 6304 KENWOOD AVENUE, SUITE 2A BALTIMORE, MD 21237 410-866-5840 1ST UNITED PLUS ESCROW 18757 BURBANK BLVD., # 201 TARZANA, CA 91356 818-881-0201 1ST UNITED TITLE & ESCROW INC 4811 LEBANON ROAD SUITE 107 HERMITAGE, TN 37076 615-874-2266 1ST WEST ESCROW 2601 FOURTH AVENUE SUITE 110 SEATTLE, WA 98121 206-733-8077 5 STAR ESCROW 2333 BROADWAY, SUITE #210 SANTA ANA, CA 92706 714-866-2141 8RESTON TITLE 5045 LORIMAR #180 PLANO TX 75093 972-608-1888 A. DEAN MILITE ESQUIRE 151 MYSTIC AVENUE SUITE 1 MEDFORD, MA 02155 781-386-0954 A.C.T ESCROW INC. 42231 6TH STREET WEST, SUITE 205 LANCASTER, CA 93534 phone A+ ESCROW 7676 HAZARD CENTER DRIVE #150 SAN DIEGO, CA 92108 619-497-4961 A+ ESCROW 1702 KETTNER BLVD C-1 SAN DIEGO, CA 92101 619-595-1241 A-1 CLOSING INC 1303 N DIVISION , SUITE A SPOKANE, WA 99202 509-927-8848 A-1 ESCROW 333 NORTH ANITA AVENUE #7 ARCADIA, CA 91006 626-447-2117 A-1 TITILE SERVICES-DC 5 MOONCON CIRCLE WALDORF, MD 20602 301-396-9390 A-1 TITLE 5959 SHALLOWFORD ROAD CHATTANOOGA, TN 37421 523-553-8254 AAA TITLE PROFESSIONALS INC. -

My Life's Story

My Life’s Story By Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz 1915-2000 Biography of Lieutenant Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Z”L , the son of Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Shwartz Z”L , and Rivka Shwartz, née Klein Z”L Gilad Jacob Joseph Gevaryahu Editor and Footnote Author David H. Wiener Editor, English Edition 2005 Merion Station, Pennsylvania This book was published by the Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Memorial Committee. Copyright © 2005 Yona Shwartz & Gilad J. Gevaryahu Printed in Jerusalem Alon Printing 02-5388938 Editor’s Introduction Every Shabbat morning, upon entering Lower Merion Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation on the outskirts of the city of Philadelphia, I began by exchanging greetings with the late Lt. Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz. He used to give me news clippings and booklets which, in his opinion, would enhance my knowledge. I, in turn, would express my personal views on current events, especially related to our shared birthplace, Jerusalem. Throughout the years we had an unwritten agreement; Eliyahu would have someone at the Israeli Consulate of Philadelphia fax the latest news in Hebrew to my office (Eliyahu had no fax machine at the time), and I would deliver the weekly accumulation of faxes to his house on Friday afternoons before Shabbat. This arrangement lasted for years. Eliyahu read the news, and distributed the material he thought was important to other Israelis and especially to our mutual friend Dr. Michael Toaff. We all had an inherent need to know exactly what was happening in Israel. Often, during my frequent visits to Israel, I found that I was more current on happenings in Israel than the local Israelis. -

ILH MAP 2014 Site Copy

Syria 99 a Mt.Hermon M 98 rail Odem Lebanon T O Rosh GOLAN HEIGHTS 98 Ha-Nikra IsraelNational 90 91 C Ha-Khula 899 Tel Hazor Akhziv Ma’alot Tarshiha 1 Nahariya 89 89 Katzrin More than a bed to sleep in! L. 4 3 888 12 Vered Hagalil 87 Clil Yehudiya Forest Acre E 85 5 4 Almagor 85 85 6 98 Inbar 90 Gamla 70 Karmiel Capernaum A 807 79 GALILEE 65 -212 meters 92 Givat Yoav R 13 -695 11 2 70 79 Zippori 8 7 75 Hilf Tabash 77 2 77 90 75 Nazareth 767 Khamat Israel’s Top 10 Nature Reserves & National Parks 70 9 Yardenit Gader -IS Mt. Carmel 10 Baptismal Site 4 Yoqneam Irbid Hermon National Park (Banias) - A basalt canyon hiking trail leading Nahal 60 S Me’arot to the largest waterfall in Israel. 70 Afula Zichron Ya’acov Megiddo 65 90 Yehudiya Forest Nature Reserve - Come hike these magnicent 71 trails that run along rivers, natural pools, and waterfalls. 60 Beit Alfa Jisr Az-Zarqa 14 6 Beit 65 Gan Shean Zippori National Park - A site oering impressive ruins and Caesarea Um El-Fahm Hashlosha Beit mosaics, including the stunning “Mona Lisa of the Galilee”. 2 Shean Jordan TEL Hadera 65 River Jenin Crossing Caesarea National Park - Explore the 3500-seat theatre and 6 585 S other remains from the Roman Empire at this enchanting port city. Jarash 4 Jerusalem Walls National Park - Tour this amazing park and view Biblical 60 90 Netanya Jerusalem from the city walls or go deep into the underground tunnels. -

Daughters of the Vale of Tears

TUULA-HANNELE IKONEN Daughters of the Vale of Tears Ethnographic Approach with Socio-Historical and Religious Emphasis to Family Welfare in the Messianic Jewish Movement in Ukraine 2000 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the board of the School of Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Väinö Linna-Auditorium K104, Kalevantie 5, Tampere, on February 27th, 2013, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Social Sciences and Humanities Finland Copyright ©2013 Tampere University Press and the author Distribution Tel. +358 40 190 9800 Bookshop TAJU [email protected] P.O. Box 617 www.uta.fi/taju 33014 University of Tampere http://granum.uta.fi Finland Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1809 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1285 ISBN 978-951-44-9059-0 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9060-6 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://acta.uta.fi Tampereen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print Tampere 2013 Abstract This ethnographic approach with socio•historical and religious emphasis focuses on the Mission view of Messianic Jewish women in Ukraine circa 2000. The approach highlights especially the meaning of socio•historical and religious factors in the emergence of the Mission view of Messianic Jewish women. Ukraine, the location of this study case, is an ex•Soviet country of about 48 million citizens with 100 ethnic nationalities. Members of the Jewish Faith form one of those ethnic groups. Following the Russian revolution in 1989 and then the establishing of an independent Ukraine in 1991, the country descended into economic disaster with many consequent social problems. -

Israeli Housing and Education Policies for Ethiopian Jewish Immigrants, 1984-1992

The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies CCIS University of California, San Diego Politics, Race and Absorption: Israeli Housing and Education Policies for Ethiopian Jewish Immigrants, 1984-1992 By Fred A. Lazin Ben Gurion University of the Negev Working Paper 28 November 2000 Lazin / 2 Politics, Race and Absorption: Israeli Housing and Education Policies for Ethiopian Jewish Immigrants, 1984-1992 Fred A. Lazin Ben Gurion University of the Negev In response to a question about policies to absorb the recent influx of Soviet and Ethiopian immigrants (1989-1992) a former Israeli Prime Minister responded: “There was no policy... immigration itself creates solutions... and solves problems.” To the same question, a senior Jewish Agency absorption official commented: “... at the university you have ideas of vast plans... in life we do not have the time needed to make one... there is a need for quick and immediate decisions.” If education is the key to success for any group, it is doubly so for the Ethiopians. For them, it not only affects their chances for upward mobility, it plays a critical role in their integration into Israel's mainstream-modern, technological and mostly urban society (JDC, 1997). Introduction Since the early 1980s and until 1993 over 50,000 Black African Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel. Most "came from one of the most conservative, rural regions of Ethiopia, where modern means of communication and transportation were undeveloped, illiteracy among the adult population was more than 90 percent…" (Wagaw, 1993:26-28). As with previous Jewish immigrants, the Israeli government and Jewish Agency assumed responsibility to absorb them into Israeli society.1 Since independence in 1948 Israeli governments have pursued the goal of providing every Jewish immigrant a “decent home in a suitable living 1 Established in 1929 the Jewish Agency represented world Jewry and the World Zionist Organization in efforts to establish a Jewish State in Mandatory Palestine.