Extreme and Complex Variation in Range-Wide Abundances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Ecuador: Tumbesian Rarities and Highland Endemics Jan 21 – Feb 7, 2010

Southern Ecuador: Tumbesian Rarities and Highland Endemics Jan 21 – Feb 7, 2010 SOUTHERN ECUADOR : Tumbesian Rarities and Highland Endemics January 21 – February 7, 2010 JOCOTOCO ANTPITTA Tapichalaca Tour Leader: Sam Woods All photos were taken on this tour by Sam Woods TROPICAL BIRDING www.tropicalbirding.com 1 Southern Ecuador: Tumbesian Rarities and Highland Endemics Jan 21 – Feb 7, 2010 Itinerary January 21 Arrival/Night Guayaquil January 22 Cerro Blanco, drive to Buenaventura/Night Buenaventura January 23 Buenaventura/Night Buenaventura January 24 Buenaventura & El Empalme to Jorupe Reserve/Night Jorupe January 25 Jorupe Reserve & Sozoranga/Night Jorupe January 26 Utuana & Sozoranga/Night Jorupe January 27 Utuana and Catamayo to Vilcabamba/Night Vilcabamba January 28 Cajanuma (Podocarpus NP) to Tapichalaca/Night Tapichalaca January 29 Tapichalaca/Night Tapichalaca January 30 Tapichalaca to Rio Bombuscaro/Night Copalinga Lodge January 31 Rio Bombuscaro/Night Copalinga February 1 Rio Bombuscaro & Old Loja-Zamora Rd/Night Copalinga February 2 Old Zamora Rd, drive to Cuenca/Night Cuenca February 3 El Cajas NP to Guayaquil/Night Guayaquil February 4 Santa Elena Peninsula& Ayampe/Night Mantaraya Lodge February 5 Ayampe & Machalilla NP/Night Mantaraya Lodge February 6 Ayampe to Guayaquil/Night Guayaquil February 7 Departure from Guayaquil DAILY LOG Day 1 (January 21) CERRO BLANCO, MANGLARES CHARUTE & BUENAVENTURA We started in Cerro Blanco reserve, just a short 16km drive from our Guayaquil hotel. The reserve protects an area of deciduous woodland in the Chongon hills just outside Ecuador’s most populous city. This is a fantastic place to kickstart the list for the tour, and particularly for picking up some of the Tumbesian endemics that were a focus for much of the tour. -

Contents Contents

Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU CONTENTS CONTENTS PERU, THE NATURAL DESTINATION BIRDS Northern Region Lambayeque, Piura and Tumbes Amazonas and Cajamarca Cordillera Blanca Mountain Range Central Region Lima and surrounding areas Paracas Huánuco and Junín Southern Region Nazca and Abancay Cusco and Machu Picchu Puerto Maldonado and Madre de Dios Arequipa and the Colca Valley Puno and Lake Titicaca PRIMATES Small primates Tamarin Marmosets Night monkeys Dusky titi monkeys Common squirrel monkeys Medium-sized primates Capuchin monkeys Saki monkeys Large primates Howler monkeys Woolly monkeys Spider monkeys MARINE MAMMALS Main species BUTTERFLIES Areas of interest WILD FLOWERS The forests of Tumbes The dry forest The Andes The Hills The cloud forests The tropical jungle www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 1 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU ORCHIDS Tumbes and Piura Amazonas and San Martín Huánuco and Tingo María Cordillera Blanca Chanchamayo Valley Machu Picchu Manu and Tambopata RECOMMENDATIONS LOCATION AND CLIMATE www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 2 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU Peru, The Natural Destination Peru is, undoubtedly, one of the world’s top desti- For Peru, nature-tourism and eco-tourism repre- nations for nature-lovers. Blessed with the richest sent an opportunity to share its many surprises ocean in the world, largely unexplored Amazon for- and charm with the rest of the world. This guide ests and the highest tropical mountain range on provides descriptions of the main groups of species Pthe planet, the possibilities for the development of the country offers nature-lovers; trip recommen- bio-diversity in its territory are virtually unlim- dations; information on destinations; services and ited. -

Climate, Crypsis and Gloger's Rule in a Large Family of Tropical Passerine Birds

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.08.032417; this version posted April 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Climate, crypsis and Gloger’s rule in a large family of tropical passerine birds 2 (Furnariidae) 3 Rafael S. Marcondes 1,2,3, Jonathan A. Nations 1,3, Glenn F. Seeholzer1,4 and Robb T. Brumfield1 4 1. Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological 5 Sciences. Baton Rouge LA, 70803. 6 2. Corresponding author: [email protected] 7 3. Joint first authors 8 4. Current address: Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, 9 Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY, 10024, USA 10 11 Author contributions: RSM and JAN conceived the study, conducted analyses and wrote the 12 manuscript. RSM and GFS collected data. All authors edited the manuscript. RTB provided 13 institutional and financial resources. 14 Running head: Climate and habitat type in Gloger’s rule 15 Data accessibility statement: Color data is deposited on Dryad under DOI 16 10.5061/dryad.s86434s. Climatic data will be deposited on Dryad upon acceptance for 17 publication. 18 Key words: Gloger’s rule; Bogert’s rule; climate; adaptation; light environments; Furnariidae, 19 coloration; melanin; thermal melanism. 20 21 22 23 24 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.08.032417; this version posted April 9, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

NORTHERN PERU: ENDEMICS GALORE October 7-25, 2020

® field guides BIRDING TOURS WORLDWIDE [email protected] • 800•728•4953 ITINERARY NORTHERN PERU: ENDEMICS GALORE October 7-25, 2020 The endemic White-winged Guan has a small range in the Tumbesian region of northern Peru, and was thought to be extinct until it was re-discovered in 1977. Since then, a captive breeding program has helped to boost the numbers, but this bird still remains endangered. Photograph by guide Richard Webster. We include here information for those interested in the 2020 Field Guides Northern Peru: Endemics Galore tour: ¾ a general introduction to the tour ¾ a description of the birding areas to be visited on the tour ¾ an abbreviated daily itinerary with some indication of the nature of each day’s birding outings Those who register for the tour will be sent this additional material: ¾ an annotated list of the birds recorded on a previous year’s Field Guides trip to the area, with comments by guide(s) on notable species or sightings (may be downloaded from the website) ¾ a detailed information bulletin with important logistical information and answers to questions regarding accommodations, air arrangements, clothing, currency, customs and immigration, documents, health precautions, and personal items ¾ a reference list ¾ a Field Guides checklist for preparing for and keeping track of the birds we see on the tour ¾ after the conclusion of the tour, a list of birds seen on the tour Peru is a country of extreme contrasts: it includes tropical rainforests, dry deserts, high mountains, and rich ocean. These, of course, have allowed it to also be a country with a unique avifauna, including a very high rate of endemism. -

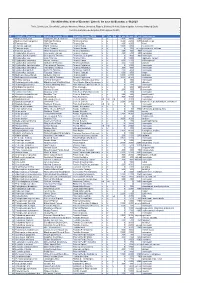

Ecuador Simple List Version 2020 Clements

Checklist of the birds of Ecuador / Lista de las aves del Ecuador, v. 08.2020 Freile, Brinkhuizen, Greenfield, Lysinger, Navarrete, Nilsson, Olmstead, Ridgely, Sánchez-Nivicela, Solano-Ugalde, Athanas, Ahlman & Boyla Comité Ecuatoriano de Registros Ornitológicos (CERO) ID Scientific_Clements_2019 English_Clements_2019 Español Ecuador CERO EC Con Gal Alt_min Alt_max Alt_ext Subespecies 1 Nothocercus julius Tawny-breasted Tinamou Tinamú Pechileonado x x 2300 3400 2100 monotypic 2 Nothocercus bonapartei Highland Tinamou Tinamú Serrano x x 1600 2200 3075 plumbeiceps 3 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou Tinamú Gris x x 400 1600 kleei 4 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou Tinamú Negro x x 1000 1400 hershkovitzi 5 Tinamus major Great Tinamou Tinamú Grande x x 0 700 1200, 1350 peruvianus, latifrons 6 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou Tinamú Goliblanco x x 200 400 900 monotypic 7 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou Tinamú Cinéreo x x 200 600 900 monotypic 8 Crypturellus berlepschi Berlepsch's Tinamou Tinamú de Berlepsch x x 0 400 900 monotypic 9 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou Tinamú Chico x x 0 1200 nigriceps, harterti 10 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou Tinamú Pardo x x 500 1100 chirimotanus? 11 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou Tinamú Ondulado x x 200 600 yapura 12 Crypturellus transfasciatus Pale-browed Tinamou Tinamú Cejiblanco x x 0 1600 monotypic 13 Crypturellus variegatus Variegated Tinamou Tinamú Abigarrado x x 200 400 monotypic 14 Crypturellus bartletti Bartlett's Tinamou Tinamú de Bartlett x x 200 400 monotypic 15 Crypturellus -

Synallaxis Stictothorax Group (Aves: Passeriformes: Furnariidae): Synallaxis Chinchipensis Chapman, 1925 As a Valid Species, with a Lectotype Designation

70 (3): 319 – 331 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2020. 2020 Alpha taxonomy of Synallaxis stictothorax group (Aves: Passeriformes: Furnariidae): Synallaxis chinchipensis Chapman, 1925 as a valid species, with a lectotype designation Renata Stopiglia 1, 2, 3,*, Flávio A. Bockmann 3, 4, Claydson P. de Assis 2 & Marcos A. Raposo 2 1 Museu de História Natural do Ceará Prof. Dias da Rocha, Centro de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Estadual do Ceará, Av. Dr. Silas Mun- guba, 1700, Campus Itaperi, 60741 – 000, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil — 2 Setor de Ornitologia, Departamento de Vertebrados, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista, s/n, 20940 – 040 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil — 3 Laboratório de Ictiologia de Ribeirão Preto, Departamento de Biologia, FFCLRP, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. dos Bandeirantes 3900, 14040 – 901 Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil — 4 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Comparada, FFCLRP, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. dos Bandeirantes 3900, 14040 – 901 Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil — * Corresponding author; email: [email protected] Submitted July 10, 2019. Accepted July 6, 2020. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/vertebrate-zoology on August 7, 2020. Published in print on Q3/2020. Editor in charge: Martin Päckert Abstract The Synallaxis stictothorax group comprises poorly understood South American Furnariidae. This paper aims to present the morphological and nomenclatural aspects of this group, re-describing its valid species and to propose a fresh nomenclatural treatment for group members. Our analysis corroborated the specifc status of the disputed taxon Synallaxis chinchipensis and refuted the diagnostic characteristics of the subspecies Synallaxis stictothorax maculata. Following the recommendations of the Code, a lectotype was designated to the nominal species Synallaxis hypochondriaca. -

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4Th to 25Th September 2016

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4th to 25th September 2016 Marañón Crescentchest by Dubi Shapiro This tour just gets better and better. This year the 7 participants, Rob and Baldomero enjoyed a bird filled trip that found 723 species of birds. We had particular success with some tricky groups, finding 12 Rails and Crakes (all but 1 being seen!), 11 Antpittas (8 seen), 90 Tanagers and allies, 71 Hummingbirds, 95 Flycatchers. We also found many of the iconic endemic species of Northern Peru, such as White-winged Guan, Peruvian Plantcutter, Marañón Crescentchest, Marvellous Spatuletail, Pale-billed Antpitta, Long-whiskered Owlet, Royal Sunangel, Koepcke’s Hermit, Ash-throated RBL Northern Peru Trip Report 2016 2 Antwren, Koepcke’s Screech Owl, Yellow-faced Parrotlet, Grey-bellied Comet and 3 species of Inca Finch. We also found more widely distributed, but always special, species like Andean Condor, King Vulture, Agami Heron and Long-tailed Potoo on what was a very successful tour. Top 10 Birds 1. Marañón Crescentchest 2. Spotted Rail 3. Stygian Owl 4. Ash-throated Antwren 5. Stripe-headed Antpitta 6. Ochre-fronted Antpitta 7. Grey-bellied Comet 8. Long-tailed Potoo 9. Jelski’s Chat-Tyrant 10. = Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Yellow-breasted Brush Finch You know it has been a good tour when neither Marvellous Spatuletail nor Long-whiskered Owlet make the top 10 of birds seen! Day 1: 4 September: Pacific coast and Chaparri Upon meeting, we headed straight towards the coast and birded the fields near Monsefue, quickly finding Coastal Miner. Our main quarry proved trickier and we had to scan a lot of fields before eventually finding a distant flock of Tawny-throated Dotterel; we walked closer, getting nice looks at a flock of 24 of the near-endemic pallidus subspecies of this cracking shorebird. -

Endemics Galore 2016

Field Guides Tour Report Northern Peru: Endemics Galore 2016 Oct 30, 2016 to Nov 19, 2016 Richard Webster For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. After seeing Coppery Metaltail and Russet-mantled Softtail on Abra Barro Negro, the group is surveying treeline habitats at 3400m and admiring the scenery of the upper Rio Utcubamba, wondering if there are any birds out there. There were! Read on! Photo copyright guide Richard Webster. We saw a few birds! A great variety of birds, matching the great variety of habitats that unfolded during a scenic transect of magnificent northern Peru. We started the tour in the sandy Sechura Desert near Chiclayo with some endemics, including two endangered prizes: Peruvian Plantcutter and Rufous Flycatcher. Our first night in the north was at the Chaparri reserve (after, ahem, getting stuck, fortunately not an omen of problems to come), and the next morning brought a host of Tumbesian specialties at this tranquil spot. Among the highlights were Tumbes Tyrant, Hummingbird, and Sparrow, along with White-winged Guan, White-tailed Jay, White-headed Brushfinch, Peruvian Screech-Owl, Elegant Crescentchest, and Sulphur-throated Finch. We finished the day with a lovely walk on the beach, although our destination, the river mouth, was short on special birds. The preserved woodland at Batan Grande (Bosque de Pomac) provided a welcome chance again to see Peruvian Plantcutter and Rufous Flycatcher, along with Coastal Miner, Cinereous Finch, the local Tumbes Swallow, and a great variety of arid country birds. Our next destination was the west slope of Porcuya (Porculla) Pass, where two visits increased our coverage of Tumbesian species, including Piura Chat-Tyrant, Henna-hooded and Rufous- necked foliage-gleaners, Plumbeous-backed Thrush, Bay-crowned Brushfinch, Gray-and-gold Warbler, and Black-cowled Saltator. -

Highland Rarities and Tumbesian Endemics

Tropical Birding Trip Report SOUTHERN ECUADOR January 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour SOUTHERN ECUADOR: Highland Rarities and Tumbesian Endemics Main tour: 7th – 23rd January 2017 Esmeraldas Woodstar Extension: 23rd – 26th January 2017 Tropical Birding Tour Leader: Jose Illanes This Long-wattled Umbrellabird at Buenaventura was voted as one of the birds of the trip INTRODUCTION: This is often ranked among the Ecuador-based guides as their favorite trip in the country, and it is easy to see why when you view the highlights from this trip, which again produced some of South America’s most wanted birds… Our tour started in the Pacific lowlands among the mangroves and wetlands of Manglares-Churute Ecological Reserve. That got our tour off to a good start with Horned Screamer nearby, Rufous-necked Wood-Rail, and Jet Antbird. From there we traveled south to Buenaventura, one of a number of Jocotoco Conservation Foundation reserves visited on the 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report SOUTHERN ECUADOR January 2017 trip. Arguably, the Long-wattled Umbrellabird was the key bird seen there (as usual), but this was complimented by plenty of other top-notch birds too, like Club-winged Manakin, Gray-backed Hawk, Ochraceous Attila, and El Oro Parakeet (Buenaventura represents the only reliable place to see this very rare and extremely local parakeet). Between Buenaventura and our next Jocotoco Foundation reserve, Jorupe, we added yet more quality to the bird list with specialties like White-headed Brushfinch. Jorupe is a hotspot for endemics of the Tumbesian region, one of the richest mainland areas for endemics in the world, and this tour proved no different; the excellent feeders produced White-tailed Jay and Pale-browed Tinamou, and the reserve and day trips from there produced Watkins’s Antpitta, Ecuadorian Piculet, West Peruvian Screech-Owl, Henna-headed Foliage-Gleaner, and Elegant Crescentchest. -

The Avifauna of El Angolo Hunting Reserve, North-West Peru: Natural History Notes

Javier Barrio et al. 6 Bull. B.O.C. 2015 135(1) The avifauna of El Angolo Hunting Reserve, north-west Peru: natural history notes by Javier Barrio, Diego García-Olaechea & Alexander More Received 10 December 2012; final revision accepted 17 January 2015 Summary.—The Tumbesian Endemic Bird Area (EBA) extends from north-west Ecuador to western Peru and supports many restricted-range bird species. The most important protected area in the region is the Northwest Biosphere Reserve in Peru, which includes El Angolo Hunting Reserve (AHR). We visited AHR many times between 1990 and 2012. Among bird species recorded were 41 endemic to the Tumbesian EBA and six endemic subspecies that may merit species status, while 11 are threatened and eight are Near Threatened. We present ecological or distributional data for 29 species. The Tumbesian region Endemic Bird Area (EBA) extends from Esmeraldas province, in north-west Ecuador, south to northern Lima, on the central Peruvian coast (Stattersfield et al. 1998). It covers c.130,000 km2 and supports one of the highest totals of restricted-range bird species: 55 according to Stattersfield et al. (1998), or 56 following Best & Kessler (1995), the third largest number of endemic birds at any EBA globally. Within the EBA, in extreme north-west Peru, the Northwest Biosphere Reserve (NWBR) covers more than c.200,000 ha, with at least 96% forest cover (cf. Fig 38 in Best & Kessler 1995: 113, where all solid black on the left forms part of the NWBR). This statement is still valid today (Google Earth). The NWBR covers the Cerros de Amotape massif, a 130 km-long cordillera, 25–30 km wide at elevations of 250–1,600 m, running parallel to the main Andean chain (Palacios 1994). -

Northern Peru

North Peru, July-August 2013 Leader: Fabrice Schmitt Birding The North of Peru is one of the best birding experience in South America!! Dry forest, arid scrubs, cloud and ridge forests, lowland evergreen tropical forest, puna grassland, desertic canyon slopes, etc... the whole trip is a succesion of different and amazing habitats! Visiting so diverse and different ecosystems, it is not surprising that some of the species found here are some of the most sought after for any keen birder: Long-whiskered Owlet, Marvelous Spatuletail, Pale-billed Antpitta, Tumbes Tyrant, Rufous Flycatcher, Peruvian Plantcutter, White- winged Guan, Yellow-scarfed Tanager, Bar-winged Wood-wren, and so many more!! The aim of this longer trip was to photograph some of the best birds found in that part of Peru. The itinerary had been designed to have the best chance to photograph the main targets of the trip: Peruvian endemics, Tapaculos and Antpittas, particular Furnaridae, and some species like Spotted Rail, Inca-finches, Pale-billed Antpitta, rare hummingbirds, etc… Manu Expeditions Quality Wildlife & Birding Tours www.Birding-In-Peru.com [email protected] We also spend several mornings and evening looking for nightbirds, and we finished the trip with a total of 28 nightbird species contacted during the trip!! A very successful trip, with a final list close to 550 species contacted. The Marañon canyon near Balsas (picture Fabrice Schmitt) Manu Expeditions Quality Wildlife & Birding Tours www.Birding-In-Peru.com [email protected] DAY BY DAY ACTIVITIES August 28th: International flight to Lima and Chiclayo. Night in Chiclayo August 29th: Chaparri reserve Early drive to Chongoyape, entrance of the the private Chaparri reserve, owned by the local community of Santa Catalina de Chongoyape. -

Developing Tools for Improved Population and Range Estimation in Support of Extinction Risk Assessments for Neotropical Birds

Developing tools for improved population and range estimation in support of extinction risk assessments for Neotropical birds Author Christian Devenish A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology School of Science and the Environment Faculty of Science and Engineering Manchester Metropolitan University January 2017 Cover Photo: Myiarchus semirufus, Gary Rosenberg ii Developing tools for improved population and range estimation in support of extinction risk assessments for Neotropical birds Author Christian Devenish Supervisory team Stuart Marsden, MMU Graeme Buchanan, RSPB Graham Smith, MMU One of the two objects of my Peruvian journey and of our last passage over the Chain of the Andes failed; but on the other hand I had, at the critical moment, the rare good fortune of a perfectly clear day, during a very unfavourable season of the year, on the misty coast of Low Peru. I observed the passage of Mercury over the Sun at Callao, an observation which has become of some importance towards the exact determination of the longitude of Lima, and of all the south-western part of the New Continent. Thus in the intricate relations and graver circumstances of life, there may often be found, associated with disappointment, a germ of compensation. Aspects of Nature. 1849. Alexander von Humboldt iii iv General Abstract Species abundance and distribution metrics are cornerstones of conservation planning, for example, in establishing extinction risk and selecting priority areas, but abundance data are scarce and costly to obtain in comparison to those on species occurrence.