Hr-131 Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The #Operaclass Education Kit

the #operaclass Education Kit #operaclass Education Kit: Carmen 1 Table of Contents Introduction to the Education Kit for Carmen ................................................................................ 3 Is Opera Relevant? ........................................................................................................................ 4 What To Expect From Carmen ....................................................................................................... 5 The Story ...................................................................................................................................... 6 The Background ............................................................................................................................ 8 Who’s Who in Carmen .................................................................................................................. 9 Key Elements of the Story ........................................................................................................... 10 Activity 1 - Carmen ...................................................................................................................... 11 Classroom Activity – ‘Love is a rebellious bird’ – Carmen’s Habanera .................................................... 11 Activity 2 – ‘Sweet memories of home’ ....................................................................................... 14 Classroom Activity –‘Parle moi de ma mere’ ......................................................................................... -

Georges Bizet

Cronologia della vita e delle opere di Georges Bizet 1838 – 25 ottobre: nasce a Parigi Alexandre-César-Léopold, figlio di Adolph-Armand, modesto maestro di canto, e di Aimée-Marie Delsarte, buona pianista. Il bambino sarà poi battezzato col nome di Georges. 1847 – Frequenta come uditore il corso di pianoforte di Antoine-François Marmontel. 1848-52 – Al Conservatorio di Parigi studia contrappunto e fuga con Pierre Zimmermann, allievo di Cherubini; segue anche qualche lezione con Charles Gounod, che influisce fortemente sulla sua formazione. Sviluppa le doti di pianista continuando a studiare nella classe di Marmontel e ottiene diversi premi riservati agli allievi. 1853 – Alla morte di Zimmermann, frequenta i corsi di composizione di Jacques Halévy. 1854 – Prime composizioni: Grande valse de concert in mi bemolle maggiore e Nocturne in fa maggiore. 1855 – Ouverture in la minore, Sinfonia in do maggiore, Valse in do maggiore per coro e orchestra. 1856 – È secondo al Prix de Rome con la cantata David . 1857 – L’operetta in un atto Le Docteur Miracle , vincitrice (ex equo con Charles Lecocq) di un premio offerto da Offenbach, debutta con successo al Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens. Con la cantata Clovis et Clotilde il compositore si aggiudica il Prix de Rome: può così godere per cinque anni di una sovvenzione statale e soggiornare per due anni in Germania e in Italia. 1858 – In gennaio raggiunge Roma. Si stabilisce a Villa Medici, sede italiana dell’Académie Française che ospita i vincitori del Prix de Rome. Scrive un Te Deum e in estate va in vacanza sui Colli Albani. Musica un libretto di soggetto italiano, Don Procopio , che invia all’Académie Française. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List Leonard Bernstein Candide Role: Candide Volkstheater Rostock: Director Johanna Schall, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2016 A Quiet Place Role: François Theater Lübeck: Director Effi Méndez, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2019 Ludwig van Beethoven Fidelio Role: Jaquino Nationaltheater Mannheim 2017: Director Roger Vontoble, Conductor Alexander Soddy Georges Bizet Carmen Role: Don José (English) Garden Opera: Director Saffron van Zwanenberg 2013/2014 OperaUpClose: Director Rodula Gaitanou, April-May 2012 Role: El Remendado Scottish Opera: Conductor David Parry, 2015 (cover) Melbourne City Opera: Director Blair Edgar, Conductor Erich Fackert May 2004 Role: Dancaïro Nationaltheater Mannheim: Director Jonah Kim, Conductor Mark Rohde, 2019/20 Le Docteur Miracle Role: Sylvio/Pasquin/Dr Miracle Pop-Up Opera: March/April 2014 Benjamin Britten Peter Grimes Role: Peter Grimes (cover) Nationaltheater Mannheim: Conductor Alexander Soddy, Director Markus Dietz 2019/20 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Role: Lysander (cover) Garsington Opera: Conductor Steauart Bedford, Director Daniel Slater June-July 2010 Francesco Cavalli La Calisto Role: Pane Royal Academy Opera: Dir. John Ramster, Cond. Anthony Legge, May 2008 Gaetano Donizetti Don Pasquale Role: Ernesto (English) English Touring Opera: Director William Oldroyd, Conductor Dominic Wheeler 2010 Lucia di Lammermoor Role: Normanno Nationaltheater Mannheim 2016 Jonathan Dove Swanhunter Role: Soppy Hat/Death’s Son Opera North: Director Hannah Mulder, Conductor Justin Doyle April -

Walton - a List of Works & Discography

SIR WILLIAM WALTON - A LIST OF WORKS & DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Martin Rutherford, Penang 2009 See end for sources and legend. Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Catalogue No F'mat St Rel A BIRTHDAY FANFARE Description For Seven Trumpets and Percussion Completion 1981, Ischia Dedication For Karl-Friedrich Still, a neighbour on Ischia, on his 70th birthday First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Recklinghausen First 10-Oct-81 Westphalia SO Karl Rickenbacher Royal Albert Hall L'don 7-Jun-82 Kneller Hall G E Evans A LITANY - ORIGINAL VERSION Description For Unaccompanied Mixed Voices Completion Easter, 1916 Oxford First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.03 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - FIRST REVISION Description First revision by the Composer Completion 1917 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.14 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - SECOND REVISION Description Second revision by the Composer Completion 1930 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel St Johns, Cambridge ? Jan-62 George Guest St Johns, Cambridge 01a ARG ZRG -

Sea Symphony Prog Final

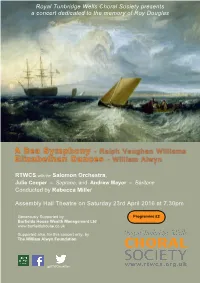

Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society presents a concert dedicated to the memory of Roy Douglas RTWCS with the Salomon Orchestra, Julie Cooper – Soprano, and Andrew Mayor – Baritone Conducted by Rebecca Miller Assembly Hall Theatre on Saturday 23rd April 2016 at 7.30pm Generously Supported by Programme £2 Burfields House Wealth Management Ltd www.burfieldshouse.co.uk Supported also, for this concert only, by The William Alwyn Foundation @RTWChoralSoc This concert is dedicated to the memory of our late president, Roy Douglas, who died in 2015 at the age of 107. Roy became President of the Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society in the late 1980s and continued in that office until his death on March 23rd 2015. He took a great interest in all our activities and always attended our concerts as long as he was able. Roy was a most distinguished musician, both on his own account and in support of other great British composers, including William Walton and, notably, Ralph Vaughan Williams whose music we will perform today. In addition to being President of RTWCS, Roy was also President of the Royal Tunbridge Wells Symphony Orchestra. Many local musicians, as well as the wider musical world, owe Roy a huge debt of gratitude. — Programme — The National Anthem (to be sung by the choir) Elizabethan Dances by William Alwyn No. 1. Moderato e ritmico No. 2. Waltz tempo - languidamente No. 3. Allegro scherzando (ma non troppo allegro) No. 4. Moderato No. 5. Poco allegretto e semplice No. 6. Allegro giocoso — INTERVAL — A Sea Symphony (Symphony no. 1) by Ralph Vaughan Williams Part 1. -

Carmen, Chœur Des Enfants « Avec La Garde Montante »

Carmen, chœur des enfants « avec la garde montante » Georges Bizet Romantique France 1875 Cycle 1, Cycle 2, Cycle 3 04'25" Genre : Vocal, Musique symphonique, Opéra Thème : La marche, L’amour L’œuvre (ou l’extrait) : Cet extrait de Carmen se situe au début de l’opéra, acte I scène ii. Il s’agit d’une bande d’enfants imitant les dragons au moment de la relève de la garde, sur une place à Séville. Carmen est un opéra-comique (des scènes parlées servent de liaison entre les morceaux musicaux, le présent extrait en donne un exemple) en quatre actes sur un livret d’Henri Meilhac et Ludovic Halévy d’après la nouvelle de Prosper Mérimée. La première représentation se déroule à Paris à l’Opéra-Comique, salle Favart, le 3 mars 1875. L’accueil du public reste réservé, voire hostile : ce sujet sur une femme libre heurte la bourgeoisie de l’époque, certains journaux comparent même l’héroïne à une « femelle vomie de l’enfer ». Néanmoins, l’opéra devient rapidement populaire et il est aujourd’hui l’œuvre lyrique la plus jouée au monde. Carmen a inspiré plus d’une quinzaine de cinéastes, dont Cecil B DeMille, Charles Chaplin, Ernst Lubitsch, Otto Preminger, Carlos Saura, Jean-Luc Godard, Peter Brook…, sans parler du film de Francesco Rosi avec Julia Migenes, Plácido Domingo et Ruggero Raimondi, ou de la comédie musicale Carmen Hip Hopera avec Beyoncé. Auteur / Compositeur / Interprete : Enfant précoce, issu d’une famille de musiciens, Georges Bizet entre très jeune au Conservatoire de Paris où il étudie le piano, l’orgue et la composition. -

Douglas, Adrian Powter (Baritone) President RTWCS Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society Orchestra Leader: Jane Gomm Programme £2.50

Programme:Programme 7/2/08 4:10 pm Page 1 Sunday 18th November 2007, 3.00pm The Assembly Hall, Tunbridge Wells Conductor: Richard Jenkinson Soloists: Nicki Kennedy (soprano) In celebration of the Harriet Webb (alto) 100th birthday of Sean Clayton (tenor) Roy Douglas, Adrian Powter (baritone) President RTWCS Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society Orchestra Leader: Jane Gomm Programme £2.50 www.rtwcs.org.uk Publicity by Looker Strategic Communications 01892 518122 www.looker.co.uk RTWCS is a Registered Charity No: 273310 Programme:Programme 7/2/08 4:10 pm Page 2 ROYAL TUNBRIDGE WELLS CHORAL SOCIETY President Roy Douglas Vice President Derek Watmough MBE Musical Director and Conductor Richard Jenkinson Accompanist Anthony Zerpa-Falcon Honorary Life Members Len Lee Joyce Stredder Patrons Mrs A Bell Mr G Huntrods CBE Mrs J Stredder Miss B Benson Mr M Hudson Miss L Stroud Mrs E Carr Mrs H MacNab Mr R F Thatcher Sir Derek & Lady Day Mrs Pat Maxwell Mr D Watmough Mr R R Douglas Mr B A & Mrs E Phillips Mr M Webb Miss D Goodwin Mrs W Roszak Mr G T Weller Mr D Haley Mr I Short Mr W N Yates We are very grateful to our Patrons for their valuable support. We no longer have help to pay our production costs from the Arts Council or the Local Authority. If you would like to become a Patron and support the Society in this way please contact Gerald Chew, on 01892 527958. For £45 per annum you will receive a seat of your choice for our Spring, Autumn and Christmas concerts each season. -

William Walton (1902-1983) Belshazzar's Feast

Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society Presents A Centenary Gala Concert In the Presence of HM Lord Lieutenant of Kent Mr Allan Willett CMC and Mrs Anne Willett Special Guests The Chairman of Kent County Council Mr Kent Tucker CMG and Mrs Eileen Tucker The Mayor and Mayoress of Tunbridge Wells Borough Council Cr David Wakefield and Mrs Ruth Wakefield The Mayor of Southborough Town Council Mrs Colette March and Escort Derek Watmough MBE PROGRAMME Conductor The National Anthem Charlotte Ellett Soprano Poulenc Gloria Anthony Michaels-Moore Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue Baritone Klaus Uwe Ludwig INTERVAL Piano Walton Belshazzar's Feast English Festival Orchestra Leader Adrian Levine Assembly Hall Theatre, Tunbridge Wells Combined Choirs of the Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society Sunday 30th May 2004 and the Bach-Chor Wiesbaden at 3 pm The Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society The Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society had its beginnings in the late Autumn of 1904 when an announcement in the Kent & Sussex Courier invited "Ladies and Gentlemen with good voices" to take part in rehearsals of Brahms' Requiem, conducted by Mr Francis J Footc. There was a good response to this invitation. On November 25™ the Courier reported that there were nearly 100 voices, but there were still vacancies for Tenors and Basses - this, in spile of the fact that there was already a large choir in the town known as the Tunbridge Wells Vocal Association. The performance of Brahms' Requiem took place on Wednesday, 10™ May 1905 in the Great Hall and there was a glowing report in the Courier only two days iater. -

Ealing and Denham – Golden Years for British Film And

Ealing and Denham – golden years for British film and British film music By Mark Fishlock ritish film Armstrong … the Bcomposers list goes on. continue to punch well above their While British weight. David composers hold Arnold has another their own against Bond score under their American his belt, while counterparts, the George Fenton, British film Dario Marianelli, industry itself Rolfe Kent and Mark ducks in and out of Thomas have all had rude health, very busy years. frequently confounding those Several years ago, who announce its Stanley Myers demise. helped opened doors for Hans There are the Zimmer and George Auric and Ernest Irving golden periods, following the success of ‘Rain Man’in 1988, the former Buggles such as the gritty urban dramas of the sixties and the self- synth man decamped to Hollywood and proceeded to offer a confidence of the early eighties when ‘Chariots of Fire’ leg-up to a number of British composers,including Harry and scriptwriter Colin Welland confidently announced to the Rupert Gregson-Williams,John Powell,and Nick Glennie-Smith. Oscars audience that “the British are coming”.Hollywood patted the old country on the head and got on with making blockbusters. Another golden age of British cinema was the 1940s and two studios that generate particularly moist-eyed reverence of film enthusiasts are Ealing and Denham. This period arguably began in 1938 when Michael Balcon took over as Head of Production at Ealing and lasted until the mid fifties, by which time the studio had turned out British masterpieces such as ‘The Ladykillers’,‘Passport to Pimlico’ and ‘The Lavender Hill Mob’. -

Carmen Production Photo by David Bachman

Pittsburgh Opera 2015 Carmen production photo by David Bachman Carmen: Shocking character, successful opera by Jill Leahy Libretto by Henri Meilhac Henriand Halévy by Ludovic Libretto French composer Georges Bizet was named Alexandre César Léopold Bizet armen ● at birth and grew up surrounded by music—his father was a singing teacher and his mother a fine pianist. A prodigy, Bizet was accepted into the Paris C Conservatoire at the age of nine; his teachers included Antoine-François Marmontel, Fromental Halévy (one of the founders of French grand opera, whose daughter Bizet married), and the composer Charles Gounod. In 1857, at the age of 19, Bizet wrote an operetta Georges Bizet (Le Docteur Miracle) for a competition organized by Jacques Offenbach. Bizet shared the first prize, Miracle was staged, and his name became known in Music by Music by the best musical circles. He attended Rossini’s famous Saturday evening soirées and won the Prix de Rome from the Académie de Musique. After three happy years in Italy, Bizet returned to Paris and unhappiness. He had few successes, his mother died, and his first opera of any significance in Paris, The Pearl Fishers (1863), was praised by Berlioz but disparaged by most others. Bizet’s only success was The Pretty Maid of Perth (1867), which earned praise at the time but is rarely performed today. (1838–1875) Georges Bizet In 1873, the Opéra-Comique in Paris commissioned Bizet to write an opera. He chose Prosper Mérimée’s novella Carmen (1845) and worked closely with librettists Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy. Carmen faced many obstacles e to the Opera in reaching the stage—many considered the story too salacious for public performance, and critics denounced Carmen as immoral even before it was complete. -

Dorking Celebrates VW in This Issue

Journal of the No.21 June 2001 EDITOR Stephen Connock RVW (see address below) Society Dorking Celebrates VW In this issue... A striking new statue of Vaughan Williams, located outside Scott of the Antarctic Dorking Halls, was unveiled on Thursday 19th April 2001. Part 2 Ursula Vaughan Williams was the Guest of Honour and she was accompanied by the sculptor, William Fawke. The G ceremony was attended by over a hundred people. Uniquely, Sinfonia Antartica Brian Kay conducted the gathering in the street in a Introduction and CD Review memorable rendering of VW’s Song for a Spring Festival to by Jonathan Pearson . 3 words by Ursula Wood. Leith Hill Music Festival G The music for Scott of the Antartic Councillor Peter Seabrook referred to RVW’s long by Christopher J. Parker . 11 connection with Dorking. As a child he had lived at Leith Hill Place and he returned to live near Dorking from 1929 to 1953. He was conductor of the Leith Hill Music Festival The Times, The Times from1905 to 1953, an astonishing 48 years, and returned after and the Fourth 1953 to conduct performances of the St Matthew Passion until 1958. RVW had also supported the building of the Symphony Dorking Halls, so the placing of the statue outside the Halls by Geoff Brown . 15 was entirely right. Finally, Councillor Seabrook paid tribute to the sculptor, William Fawke, and to Adrian White CBE whose financial support for the project had been vital. And more …… Recognition CHAIRMAN Stephen Connock MBE It is welcome news that Surrey County Council 65 Marathon House, commissioned this lifelike sculpture to add 200 Marylebone Road, further recognition to Vaughan Williams’ London NW1 5PL remarkable contribution to English music in Tel: 01728 454820 general and to Dorking in particular.