L O U I S I a N a Statewide Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ECOLOGY of BOTTOMLAND HARDWOOD SWAMPS of the SOUTHEAST: a Community Profile

Biological Services Program FWS/OBS-81 /37 March 1982 THE ECOLOGY OF BOTTOMLAND HARDWOOD SWAMPS OF THE SOUTHEAST: A Community Profile I 49.89 ~~:137 Fish and Wildlife Service 2 c. U.S. Department of the Interior The Biological Services Program was established within the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to supply scientific information and methodologies on key environmental issues that impact fish and wildlife resources and their supporting ecosystems. The mission of the program is as follows: • To strengthen the Fish and Wildlife Service in its role as a primary source of information on national fish and wild life resources, particularly in respect to environmental impact assessment. • To gather, analyze, and present information that will aid decisionmakers in the identification and resolution of problems associated with major changes in land and water use. • To provide better ecological information and evaluation for Department of the Interior development programs, such as those relating to energy development. Information developed by the Biological Services Program is intended for use in the planning and decisionmaking process to prevent or minimize the impact of development on fish and wildlife. Research activities and technical assistance services are based on an analysis of the issues, a determination of the decisionmakers involved and their information needs, and an evaluation of the state of the art to identify information gaps and to determine priorities. This is a strategy that will ensure that the products produced and disseminated are timely and useful. Projects have been initiated in the following areas: coal extraction and conversion; power plants; geothermal, mineral and oil shale develop ment; water resource analysis, including stream alterations and western water allocation; coastal ecosystems and Outer Continental Shelf develop ment; and systems inventory, including National Wetland Inventory, habitat classification and analysis, and information transfer. -

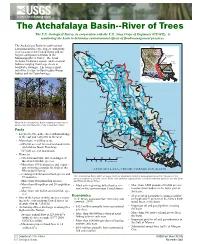

The Atchafalaya Basin

7KH$WFKDIDOD\D%DVLQ5LYHURI7UHHV The U.S. Geological Survey, in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), is monitoring the basin to determine environmental effects of flood-management practices. The Atchafalaya Basin in south-central Louisiana includes the largest contiguous river swamp in the United States and the largest contiguous wetlands in the Mississippi River Valley. The basin includes 10 distinct aquatic and terrestrial habitats ranging from large rivers to backwater swamps. The basin is most noted for its cypress-tupelo gum swamp habitat and its Cajun heritage. Water in the Atchafalaya Basin originates from one or more of the distributaries of the Atchafalaya River. Facts • Located between the cities of Baton Rouge to the east and Lafayette to the west. • More than 1.4 million acres: --885,000 acres of forested wetlands in the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway. --517,000 acres of marshland. • Home to: --9 Federal and State listed endangered/ threatened wildlife species. --More than 170 bird species and impor- tant wintering grounds for birds of the Mississippi Flyway. --6 endangered/threatened bird species and The Atchafalaya Basin offers an opportunity to implement adaptive management practices because of the 29 rookeries. general support of private, local, State, and national organizations and governmental agencies for the State --More than 40 mammalian species. and Federal Master Plans. --More than 40 reptilian and 20 amphibian • Most active-growing delta (land accre- • More than 1,000 pounds of finfish per acre species. tion) in the conterminous United States. in some water bodies in the lower part of --More than 100 finfish and shellfish spe- the basin. -

Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed As Part of Sherburne Complex

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed as part of Sherburne Complex Tom Carlisle This basin contains over one-half million acres of hardwood swamps, lakes and bayous, and is larger than the vast Okefenokee Swamp of Georgia and Florida. It is an immense This blue goose, natural floodplain of the Atchafalaya designed by J.N. River, which flows for 140 miles south “Ding” Darling, from its parting from the Mississippi has become the River to the Gulf of Mexico. symbol of the National Wildlife The fish and wildlife resources Refuge System. of the Atchafalaya River Basin are exceptional. The basin’s dense bottomland hardwoods, cypress- tupelo swamps, overflow lakes, and meandering bayous provide a tremendous diversity of habitat for many species of fish and wildlife. Ecologists rank the basin as one of the most productive wildlife areas in North America. The basin also supports an extremely productive sport and commercial fishery, and provides unique recreational opportunities to hundreds of thousands of Americans each year. Wildlife Every year, thousands of migratory waterfowl winter in the overflow swamps and lakes of the basin, located at the southern end of the great Mississippi Flyway. The lakes of the lower basin support one of the largest wintering concentrations of canvasbacks in Louisiana. The basin’s wooded wetlands also provide vital nesting habitat for wood ducks, and support the nation’s largest concentration of American America’s Great River Swamp woodcock. More than 300 species of Deep in the heart of Cajun Country, resident and migratory birds use the basin, including a large assortment at the southern end of the Lower of diving and wading birds such as egrets, herons, ibises, and anhingas. -

Atchafalaya Basin Management Coastal Wetlands Loss And

and coal geochemistry of Gulf Coast scale topographic maps (1 inch on the the elevation and shape of terrain. The coal-bearing intervals to better under- map represents 2,000 feet on the ground) maps are useful for civil engineering, stand the region’s resources. Planned for Louisiana. The maps depict land- land-use planning, resource monitoring, results of the study include geologic scape features such as lakes and streams, hiking, camping, exploring, and fishing and stratigraphic interpretations char- highways and railroads, boundaries, and expeditions. The map revisions for 1999 acterizing the coal and digital, geo- geographic names. Contour lines depict are shown in figure 6. As the Nation’s largest earth-science and ARK. graphical-referenced data bases that civilian mapping agency, the U.S. Geologi- will include stratigraphic and geochem- cal Survey (USGS) works in cooperation 92 30 Atchafalaya B. Boeuf LOUISIANA ical information. with many Federal, State, and local orga- Basin nizations to provide reliable and impartial 92 00 Baton Mapping Partnerships scientific information to resource manag- MISS. Rouge TEX. ers, planners, and others throughout the RAPIDES The USGS, in partnership with the country. This information is gathered in 31 00 AVOYELLES every state by USGS scientists to minimize Cocodrie Louisiana Office of the Oil Spill Coor- Lake GULF OF MEXICO the loss of life and property from natural dinator, several Federal agencies, and a EVANGELINE 91 30 disasters, contribute to the conservation private aerial mapping company, has B. and sound management of the Nation’s Grosse completed about 95 percent coverage ST. LANDRY POINTE natural resources, and enhance the quality COUPEE of color infrared aerial photography of of life by monitoring water, biological, Tete 30 30 ATCHAFALAYA WEST the State, as part of the National Aerial energy, and mineral resources. -

School of Renewable Natural Resources Newsletter, Fall 2006 Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons Research Matters & RNR Newsletters School of Renewable Natural Resources 2006 School of Renewable Natural Resources Newsletter, Fall 2006 Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/research_matters Recommended Citation Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, "School of Renewable Natural Resources Newsletter, Fall 2006" (2006). Research Matters & RNR Newsletters. 10. http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/research_matters/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Renewable Natural Resources at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Matters & RNR Newsletters by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fall 2006 Managing resources and protecting the environment . making a difference in the 21st century Migrating With the Ducks School of Renewable Natural Resources 1 I have explained why the focus on the breeding grounds, In the Spotlight so what is it that I am doing? First, I should point out that like most faculty, I do most of my research with the help of graduate students – well over 30 have completed degrees Migrating under my guidance. Most of that research focused on testing With the Ducks management that attempts to enhance nest success – which Frank Rohwer is the key determinant of duck production. Most attempts to George Barineau Jr. Professor of Wildlife Ecology increase duck nest success use passive measures to reduce egg predation – for example, one approach to keeping predators ON THE COVER: Frank and his labrador, Dakota, after an afternoon of checking hatched nests. -

2021 Louisiana Recreational Fishing Regulations

2021 LOUISIANA RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS www.wlf.louisiana.gov 1 Get a GEICO quote for your boat and, in just 15 minutes, you’ll know how much you could be saving. If you like what you hear, you can buy your policy right on the spot. Then let us do the rest while you enjoy your free time with peace of mind. geico.com/boat | 1-800-865-4846 Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. In the state of CA, program provided through Boat Association Insurance Services, license #0H87086. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2020 GEICO CONTENTS 6. LICENSING 9. DEFINITIONS DON’T 11. GENERAL FISHING INFORMATION General Regulations.............................................11 Saltwater/Freshwater Line...................................12 LITTER 13. FRESHWATER FISHING SPORTSMEN ARE REMINDED TO: General Information.............................................13 • Clean out truck beds and refrain from throwing Freshwater State Creel & Size Limits....................16 cigarette butts or other trash out of the car or watercraft. 18. SALTWATER FISHING • Carry a trash bag in your car or boat. General Information.............................................18 • Securely cover trash containers to prevent Saltwater State Creel & Size Limits.......................21 animals from spreading litter. 26. OTHER RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES Call the state’s “Litterbug Hotline” to report any Recreational Shrimping........................................26 potential littering violations including dumpsites Recreational Oystering.........................................27 and littering in public. Those convicted of littering Recreational Crabbing..........................................28 Recreational Crawfishing......................................29 face hefty fines and litter abatement work. -

Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Reports IGERT 2013 Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science Micah Bennett Southern Illinois University Carbondale Kelley Fritz Southern Illinois University Carbondale Anne Hayden-Lesmeister Southern Illinois University Carbondale Justin Kozak Southern Illinois University Carbondale Aaron Nickolotsky Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports A report in fulfillment of the NSF IGERT Program requirements. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0903510. Recommended Citation Bennett, Micah; Fritz, Kelley; Hayden-Lesmeister, Anne; Kozak, Justin; and Nickolotsky, Aaron, "Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science" (2013). Reports. Paper 2. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IGERT at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MULTI-USE MANAGEMENT IN THE ATCHAFALAYA RIVER BASIN: RESEARCH AT THE CONFLUENCE OF PUBLIC POLICY AND ECOSYSTEM SCIENCE BY MICAH BENNETT, KELLEY FRITZ, ANNE HAYDEN-LESMEISTER, JUSTIN KOZAK, AND AARON NICKOLOTSKY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CARBONDALE NSF IGERT PROGRAM IN WATERSHED SCIENCE AND POLICY A report -

SWAMP WARS: the FIGHT for the ATCHAFALAYA BASIN Annual

SWAMP WARS: THE FIGHT FOR THE ATCHAFALAYA BASIN Annual Report 2016-2017 A Word from Your Atchafalaya In Memoriam Basinkeeper ~Judith Zoble Gardner~ A huge welcome to our new Staff Attorney, Misha Mitchell, and new It is very hard for me to write about Judith, the wound that her Development Director, Katherine Barney. We are all very lucky to have loss left in my heart is too fresh, the thought of her passing so hard two such talented and bright new people in our movement to save our to bear. No one loved the Atchafalaya Basin more than Judith, and Basin. Their wits and talents will be put to the test as we continue working for reasons that are still a mystery to me, very few people other than to protect the Basin against all odds. my own family knew me as well as Judith did. She loved the Basin The last twelve months had been very hard for Baton Rouge, Lafayette, and many towns around the Atchafalaya Basin. Massive historic flooding and she fought valiantly to protect it. For many years, Cara and Judith has directly or indirectly affected most of our members in our region. This were like two sisters fighting together to keep ABK afloat. For many catastrophic weather event reminds us of how important is to protect the years, every single thank you letter or gift sent to our members was Basin’s wetlands: a spillway to protect us from future floods. Atchafalaya sent by Judith, and all envelops and postage were paid by Basinkeeper responded to the flood by bringing our boat to rescue people Judith and her husband in the O’Neil Lane area of Baton Rouge. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS HOUSE BILL 2 EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT. 7 01/107 Division of Administration.. 7 01/109 Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. 9 01/112 Department of Military Affairs.. 9 01/124 Louisiana Stadium and Exposition District. 10 DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS. 10 03/130 Department of Veterans Affairs. 10 03/132 Northeast Louisiana War Veterans Home. 11 03/134 Southwest Louisiana War Veterans Home.. 11 03/136 Southeast Louisiana War Veterans Home. 11 ELECTED OFFICIALS. 11 04/139 Secretary of State. 11 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT. 12 05/252 Office of Business Development. 12 DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE, RECREATION AND TOURISM. 12 06/263 Office of State Museum. 12 06/264 Office of State Parks.. 13 06/267 Office of Tourism.. 13 06/A20 New Orleans City Park.. 13 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND DEVELOPMENT. 14 07/270 Administration. 14 07/274 Public Improvements. 17 07/276 Engineering and Operations. 19 07/277 Aviation Improvements. 19 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY AND CORRECTIONS. 20 08/402 Louisiana State Penitentiary. 20 08/403 Office of Juvenile Justice. 20 08/416 Rayburn Correctional Center. 21 08/419 Office of State Police. 21 LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH.. 21 09/320 Office of Aging and Adult Services. 21 09/330 Office of Behavioral Health. 21 DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES. 22 11/431 Office of the Secretary. 22 DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE AND FISHERIES. 22 16/512 Office of the Secretary. 22 16/513 Office of Wildlife. 22 16/514 Office of Fisheries. 23 DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION. 23 19/600 LSU Board of Supervisors. 23 19/601 LSU Baton Rouge. -

Crawfish News

Crawfish News May 2010 Volume 3 Number 3 Stocking Recommendations Considerations for the 2010-2011 Production Season in Crawfish Stocking For new ponds or ponds that have been fallow for Now that we are on the downside of the production a year, stock 1 sack (35 to 45 pounds) or 2 sacks (70 to 90 season for the state’s farm-raised crawfish crop we are re- pounds) per surface acre. Use the lower rate if you think you ceiving a number of inquiries from producers on stocking may have some residual crawfish and you are stocking into crawfish. With the exception of new ponds, one reason we ponds with significant vegetative cover. Use the higher rate if have received many inquiries for information on stocking no crawfish are present and vegetative cover is sparse. is because a number of crawfish producers did not have a Stock only red swamp crawfish, and avoid, if at all pos- particularly good production year in terms of yield, and they sible, stocking of white river crawfish. want to know whether or not adding broodstock can correct Research conducted by the LSU AgCenter and the this problem. Crawfish Research Center at the University of Louisiana Stocking is usually required only in (1) new ponds, (2) Lafayette, has shown crawfish obtained from rice field ponds, ponds that have been out of production (fallow) for a year or those from permanent or marsh ponds or wild crawfish from longer and (3) when there has been a catastrophic loss of the the Atchafalaya Basin all are equally good sources of stock. -

Appendix 1. Property Ids and Names (Sorted by Name)

Appendix 1. Property IDs and Names (sorted by name) Property Name Property ID State Alexander State Forest AXSF LA Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge ARNWR NC Angelina Ranger District, Angelina National Forest ANRDANF TX Apalachicola Ranger District, Apalachicola National Forest ARDANF FL Avalon Plantation AVPL FL Avon Park Air Force Range APAFR FL Bates Hill Plantation BHPL SC Bienville Ranger District, Bienville National Forest BRDBNF MS Big Branch Marsh National Wildlife Refuge BBMNWR LA Big Cypress National Preserve BCNP FL Black Bayou Lake NWR BBLNWR LA Blackwater River State Forest BRSF FL Bladen Lakes State Forest BLSF NC Blue Tract BT NC Brookgreen Gardens BG SC Brushy Creek Experimental Forest IPBCEF TX Bull Creek & Triple N Ranch Wildlife Management Areas BCWMA FL Burroughs & Chapin Company, Grand Dunes BCCGD SC Burroughs & Chapin Company, Horry County BCCHC SC Camp Blanding CB FL Camp Mackall CM NC Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge CSNWR SC Catahoula Ranger District, Kisatchie National Forest CRDKNF LA Cheraw State Fish Hatchery CSFH SC Cheraw State Park CSP SC Chickasawhay Ranger District, DeSoto National Forest CRDDNF MS Conecuh National Forest CNF AL Cooks Branch Conservancy CBC TX Croatan Ranger District, Croatan National Forest CRDCNF NC Crosett Experimental Forest CEF AR Cumberland County Private Lands CCPL NC D'Arbonne National Wildlife Refuge DNWR LA Dare County Bombing Range DCBR NC Davy Crockett National Forest DCNF TX Desoto Ranger District, Desoto National Forest DRDDNF MS Dupuis Wildllife and Environmental Area DWEA FL Eglin Air Force Base EAFB FL Enon and Sehoy Plantation ESPL AL Escape Ranch ERANCH FL Evangeline Unit, Calcasieu RD, Kisatchie National Forest EUCRDKNF LA Fairchild State Forest FSF TX Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge FNWR AR Fort Benning FTBN GA Fort Bragg FTBG NC Fort Gordon FTGD GA Fort Jackson FTJK SC Fort Polk FTPK LA Fort Stewart FTST GA Francis Marion National Forest FMNF SC Fred C. -

Louisiana 2021-2022 Hunting & Wma Regulations

LOUISIANA 2021-2022 HUNTING & WMA REGULATIONS E-LICENSE COMING SOON! PassThe Down Hunt OutfittingOutfitting The Hunt SeriousSerious The StartsTradition SportsmenSportsmen Starts SinceSince HereHere 19671967 The Best Firearm The Best FirearmSelection in SelectionSouth in Louisiana South Louisiana • Archery • Archery • Clothing • Clothing • Footwear • Footwear• Knives • Knives Knowledgeable Staff Knowledgeable Staff FINANCING FINANCINGAVAILABLE! AVAILABLE! 3520 Ambassador Caffery Pkwy u Lafayette, LA 70503 u (337) 988-1191 www.LAFAYETTESHOOTERS.com 3520 Ambassador Caffery Pkwy u Lafayette, LA 70503 u (337) 988-1191 www.LAFAYETTESHOOTERS.com 3520 Ambassador Caffery Pkwy Lafayette, LA 70503 (337) 988-1191 www.LAFAYETTESHOOTERS.com CONTENTS Cover photo: Michael Shakes, Shutterstock.com 4. MAJOR CHANGES FOR 2021-2022 6. LICENSING 10. GENERAL HUNTING INFORMATION Hunter Education Requirements ��������������������������10 LDWF Field Office/Enforcement Office Numbers����������11 12. DEER HUNTING Chronic Wasting Disease Regulations��������������������12 Deer Area Schedules & Descriptions ��������������������13 Deer Tagging Information �������������������������������������18 Deer Hunting Regulations ������������������������������������19 23. QUADRUPEDS & RESIDENT GAME BIRDS Schedules �������������������������������������������������������������23 Methods of Take ���������������������������������������������������24 26. TURKEY Turkey Area Schedules & Descriptions �����������������26 Turkey Hunting Regulations����������������������������������27