Office on Missing Persons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

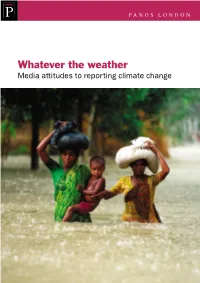

6. Whatever the Weather. Media Attitudes to Reporting Climate Change

PANOS LONDON Whatever the weather Media attitudes to reporting climate change Contents 1 Climate change and the media 1 Global policy on climate change 2 Carbon trading standards 3 The survey 4 Key findings 4 Recommendations 6 2 Case studies 7 Honduras 7 Jamaica 10 Sri Lanka 12 Zambia 14 Cover: © Panos London, 2006 Villagers returning with relief aid through heavy rains. Monsoon Panos London is part of a worldwide rains caused flooding in 40 network of independent NGOs working of Bangladesh’s 64 districts, displacing up to 30 million people with the media to stimulate debate and killing several hundred. on global development. GMB AKASH/PANOS PICTURES All photographs available from Panos Pictures www.panos.co.uk For further information contact: Environment Programme Written by Rod Harbinson with Panos London case studies by Dr Richard Mugara 9 White Lion Street (Zambia) and Ambika Chawla London N1 9PD (Sri Lanka, Jamaica and Honduras). United Kingdom Thanks to Panos Caribbean and Panos Southern Africa for Tel: +44(0)20 7278 1111 their contribution. Fax: +44(0)20 7278 0345 Designed by John F McGill [email protected] Printed by Digital-Brookdale www.panos.org.uk/environment Whatever the weather: media attitudes to reporting climate change 1 Climate change and the media 1 YOLA MONAKHOV/PANOS PICTURES The media play an important role in stimulating discussion in developing countries. Yet journalists asked by Panos say that the media have a poor understanding of the climate change debate and express little interest in it. Public discussion of the policies and issues involved is urgently needed. -

State Electronic Media During the Parliamentary Elections of October 2000

REPORT ON THE PERFORMANCE OF THE NON- STATE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DURING THE PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS OF OCTOBER 2000 Preface This Report on the Performance of the Non- State Electronic Media During the Parliamentary Elections of October 2000 is the counterpart of the Report by INFORM on The Publicly Funded Electronic Media. The Reports were prepared in collaboration with Article 19 and with the generous assistance of NORAD, The Asia Foundation and the Royal Netherlands Embassy. The issue of media performance at the time of elections is an extremely pertinent one for a variety of reasons. Of especial importance is the division within Sri Lanka between state and non-state media and the impact this has on the performance of the media during election time. Issues of agenda setting, partisan bias and stereotype invariably surface and in turn confirm that partisan allegiance characterizes media in Sri Lankan irrespective of type of ownership and management. Consequently, the role of the media in helping citizens to make informed choices at elections is seriously diminished and the need for greater professionalism in the media reinforced. This Report highlights these issues through an analysis of election reportage. It concludes with a set of recommendations which have been classified into the mandatory and the voluntary. CPA believes that the issue of media reportage at election times is integral to strengthening the institutions of a functioning democracy in Sri Lanka and of fundamental importance in enhancing the contribution of civil society to better governance. This Report, its conclusions and recommendations are presented in this spirit and in the hope that electronic media reportage at election time can develop in the near future, into an example of media best practice in Sri Lanka. -

Sri Lanka Media Audience Study 2019: Consuming News in Turbulent Times

Consuming News in Turbulent Times: Sri Lanka Media Audience Study 2019 1 Sri Lanka Media Audience Study 2019: Consuming News in Turbulent Times November 2020 2 Consuming News in Turbulent Times: Sri Lanka Media Audience Study 2019 Consuming News in Turbulent Times: Sri Lanka Media Audience Study 2019 Published in Sri Lanka by International Media Support (IMS) Authors: Nalaka Gunawardene With inputs from Arjuna Ranawana Advisers: Ranga Kalansooriya, PhD Emilie Lehmann-Jacobsen, PhD Lars Thunø Infographics: Nalin Balasuriya Dharshana Karunathilake Photos: Nisal Baduge Niroshan Fernando © November 2020 IMS The content of this publication is copyright protected. International Media Support is happy to share the text in the publication under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a summary of this license, please visit http://creative commons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0. IMS is a non-profit organisation working to support local media in countries affected by armed conflict, human insecurity and political transition. IMS has engaged Sri Lanka through partners since 2003. www.mediasupport.org Consuming News in Turbulent Times: Sri Lanka Media Audience Study 2019 3 Contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction 10 2. Methodology 13 2.1 Data collection 13 2.1.1 Phase I: Qualitative Phase 13 2.1.2 Phase II: Quantitative Phase 14 2.2 Study limitations 15 3. Findings 16 3.1 Value of news: How important is news and current information? 16 3.2 What qualities do audiences want to see in news coverage? 19 3.3 News sources: -

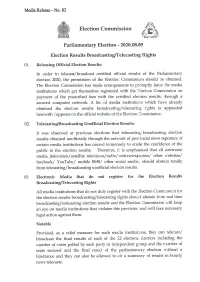

PE 2020 MR 82 E.Pdf

Election Commission – Sri Lanka Parliamentary Election - 05.08.2020 Registered electronic media to disseminate certified election results Last Updated Online Social Media No Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites (FB/ SMS Paper Web Sites) YouTube/ Twitter) 1 Telshan Network TNL TV - - - - - (Pvt) Ltd 2 Smart Network - - - www.lankasri.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 3 Bhasha Lanka (Pvt) - - - www.helakuru.lk - - Ltd 4 Digital Content - - - www.citizen.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 5 Ceylon News - - www.mawbima.lk, - - - Papers (Pvt) Ltd www.ceylontoday.lk Independent ITN, Lakhanda, www.itntv.lk, ITN Sri Lanka 6 Television Network Vasantham TV Vasantham - www.itnnews.lk (FB) - Ltd FM Lakhanda Radio (FB) Sri Lanka City FM 7 Broadcasting - - - - - Corporation (SLBC) Asia Broadcasting Hiru FM. 8 Corparation Hiru TV Shaa FM, www.hirunews.lk, Sooriyan FM, - www.hirugossip.lk - - Sun FM, Gold FM 9 Asset Radio Broadcasting (Pvt) - Neth FM - www.nethnews.lk NethFM(FB) - Ltd 1/4 File Online Number Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites Social Media SMS Paper Web Sites) Asian Media 10 Publications (Pvt) ltd - - www.thinakkural.lk - - - 11 EAP Broadcasting Swarnavahini Shree FM, - www.swarnavahini.lk, - - Company Ran FM www.athavannews.com 12 Voice of Asia Siyatha TV Siyatha FM - - - - Network (Pvt)Ltd Star tamil TV MTV Channel (Pvt) Sirasa TV, Sirasa FM, News 1st (FB), News 1st SMS 13 Ltd / MBC Shakthi TV, Shakthi FM, News 1st (S,T,E), Networks (Pvt) Ltd TV1 Yes FM, - www.newsfirst.lk (Youtube), KIKI mobile YFM, News 1st App Legends FM (Twitter) -

A Case Study of Sri Lankan Media

C olonials, bourgeoisies and media dynasties: A case study of Sri Lankan media. Abstract: Despite enjoying nearly two centuries of news media, Sri Lanka has been slow to adopt western liberalist concepts of free media, and the print medium which has been the dominant format of news has remained largely in the hands of a select few – essentially three major newspaper groups related to each other by blood or marriage. However the arrival of television and the change in electronic media ownership laws have enabled a number of ‘independent’ actors to enter the Sri Lankan media scene. The newcomers have thus been able to challenge the traditional and incestuous bourgeois hold on media control and agenda setting. This paper outlines the development of news media in Sri Lanka, and attempts to trace the changes in the media ownership and audience. It follows the development of media from the establishment of the first state-sanctioned newspaper to the budding FM radio stations that appear to have achieved the seemingly impossible – namely snatching media control from the Wijewardene, Senanayake, Jayawardene, Wickremasinghe, Bandaranaike bourgeoisie family nexus. Linda Brady Central Queensland University ejournalist.au.com©2005 Central Queensland University 1 Introduction: Media as an imprint on the tapestry of Ceylonese political evolution. The former British colony of Ceylon has a long history of media, dating back to the publication of the first Dutch Prayer Book in 1737 - under the patronage of Ceylon’s Dutch governor Gustaaf Willem Baron van Imhoff (1736-39), and the advent of the ‘newspaper’ by the British in 1833. By the 1920’s the island nation was finding strength as a pioneer in Asian radio but subsequently became a relative latecomer to television by the time it was introduced to the island in the late1970’s. -

Journalism Training and Research in Sri Lanka

Journalism Training and Research in Sri Lanka A Report on how Sida can Support Improvement of Media Quality Stig Arne Nohrstedt Sunil Bastian Jöran Hök April 2002 SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY Department for Democracy and Social Development Contents Summary...........................................................................................1 Introduction .......................................................................................2 The Assignment .................................................................................2 Background: Sri Lanka during the Last Two Decades ..........................4 1. General political development ................................................................... 4 2. Media in a conflict-ridden society .............................................................. 5 The Present Situation .........................................................................8 1. The Sri Lanka media landscape ............................................................... 8 2. Journalism Education and Research ....................................................... 13 Several Proposals for Mass Media Training and Research .................16 1. A Mass Media Institute ........................................................................... 16 2. The Thomson Report (2000) .................................................................. 16 3. The Governmental Proposal (2001)........................................................ 16 4. The Ongoing Process (2002) .................................................................. -

St. John's College Magazine

ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE MAGAZINE This is an e-version of the Magazine published by St. John’s College Jaffna since 1904. Photo gallery of the college events has been excluded in this e-version due to file compression. VOL. CII 2011 Tel: (0094) 021 222 2432 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.jaffnastjohnscollege.com Address: Main Street, Chundikuli, Jaffna, SRI LANKA CONTENTS Prayer i Editorial ii Our New Bishop 01 Annual Prize Giving 02 Principal’s Prize Day Report 06 Prize Day Address 23 Annual Reports Primary School 26 Middle School 31 Junior Secondary Level 33 Retirements S. Antonypillai 35 S. Kandasamy 37 V.K. Sriskandarajah 39 Appreciations Ven. Joseph Sarvananthan 41 R. Baveesan 43 D.J. Thevathason 45 V. Sivasubramaniam 49 T. Mylvaganam 51 V.S. Stephen 53 Jimmy Rajaratnam 55 M. Gurusamy 61 Annual Reports - Old Boys’ Associations Jaffna 63 South Sri Lanka 66 Toronto 72 Teachers’ Guild Report 75 Staff List 76 Students’ Section - English 81 Students’ Section - Tamil 96 Clubs and Associations 107 Games and Athletics 133 Team List 148 House Reports 156 Prize List 159 College Song 178 PRAYER Creator of all things, true source of light and wisdom, origin of all being, graciously let a ray of your light penetrate the darkness of my understanding. Take from me the double darkness in which I have been born, an obscurity of sin and ignorance. Give me a keen understanding, a retentive memory, and the ability to grasp things correctly and fundamentally. Grant me the talent of being exact in my explanations and the ability to express myself with thoroughness and charm. -

Developing a Strategy for Interventions in Media for Smes in Sri Lanka

Consultancy Report Prepared: 14th September 2005 Developing a strategy for interventions in media for SMEs in Sri lanka Undertaken for the ILO Enterprise for pro-poor growth project in Sri Lanka Gavin Anderson Gavin Anderson: 14th September 2005 1 Contents 1. Background 3 1.1 Enterprise for Pro-Poor Growth Project 3 1.2 Interventions in media and enterprise development 3 1.3 Terms of Reference 4 2. Activities undertaken under the consultancy 4 3. Media landscape in Sri Lanka 5 3.1 Media access 5 3.2 Radio Broadcasting in Sri Lanka 6 3.2.1 Private radio broadcasting 6 3.2.2 National state radio broadcasting 7 3.2.3 Regional state radio broadcasting 7 3.2.4 ‘Community’ radio 8 3.2.5 Relative popularity of radio stations 8 3.2.6 Programming on radio in Sri Lanka 9 3.3 TV Broadcasting 9 3.3.1 Commercial TV 10 3.3.2 State TV 10 3.3.3 Relative popularity of TV stations 10 3.3.4 Programming on TV in Sri Lanka 10 3.4 Print Media 11 3.4.1 Business publications 11 3.4.2 Local Newspapers 12 3.5 Media bias and freedom of expression 12 3.6 Media research in Sri Lanka 12 3.7 Advertising in Sri Lanka 13 3.8 Donor activities in media in Sri Lanka 14 3.9 Coverage of SMEs in the media in Sri Lanka 14 4. Recommendations for a preliminary project strategy 15 4.1 Feasibility of an intervention 15 4.2 Focus of an intervention 15 4.3 Key constraints to be addressed 16 4.4 Draft project approach and strategy 16 4.4.1 Objective of the activity 16 4.4.2 project rationale 17 4.4.3 Proposed methodology 17 4.5 Human Resources and project management 21 4.6 Project timing 22 4.7 Activity costs 23 4.8 Monitoring and Evaluation 24 4.9 Linkages to other project components 24 5. -

Guide to Media 2019

GUIDE TO MEDIA 2019 Department of Government Information – Sri Lanka ~ 1 ~ CONTENT Page No MINISTRY OF PARLIAMENTARY REFORMS AND MASS MEDIA 03 DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT INFORMATION 04 - 05 MEDIA SPOKESMAN FOR SL ARMY 06 MEDIA SPOKESMAN FOR NAVY 07 MEDIA SPOKESMAN FOR SL AIR FORCE 07 MEDIA SPOKESMAN FOR SL POLICE 08 PRINT MEDIA 09 - 25 RADIO CHANNELS 26 - 40 TV CHANNELS 41-51 MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS 52- 59 FOREIGN MEDIA 60 - 67 DISTRICT INFORMATION OFFICERS 68 ~ 2 ~ Government Information Department MINISTRY OF MASS MEDIA GUIDE TO “ASIDISI MEDURA” NO. 163, KIRULAPONE AVENUE, POLHENGODA, COLOMBO 05 GEN. NO: 2513467, 2512324, 2513459, 2513498, 2512321 MEDIA 2019 FAX: 2512346, 2512343, 2513462, 2513458,2513437 EMAIL : [email protected] Name Telephone Fax Office Mobile WhatsApp Hon. Minister of Mass Media and Dinendra Ruwan Wijayawardene 2513509 0773302100 2513506 State Minister of Difence Secretary Sunil Samaraweera 2513467 0773447077 2513458 Additional secretary (Admin) Ramani Gunawardhana 2513398 0777259711 2512346 Additional secretary (Development & planning) (act.) U.P.L.D. pathirana 2513943 0714425435 2512343 Senior Assistant Secretary N. Wasanthika Dias 2514631 0714264076 2513462 Director Planning W.A.P. Wellappuli 2513470 0714076273 0714076273 2514351 Director (Development) J.W.S. Kithsiri 2513644 0712882052 0718025551 Director (Media) K.P. Jayantha 2513469 0773996320 0773996320 2513463 Assistant Secretary M.P. Bandara 2512524 0718663924 0718663924 Assistant Director (Planning) M.C.S. Devasurendra 2513466 0773510168 0773510168 2513466 Accountant B.R Ranasinghe 2513442 0716462371 0716462371 2513442 Legal Officer D.P.U. Welarathne 2513468 0773301917 0773301917 2513468 Administrative Officer Indrani Vitharana 2512052 0710659800 2513462 ~ 3 ~ DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT INFORMATION Government Information NO. 163, KIRULAPONE AVENUE, POLHENGODA, COLOMBO 05 Department GEN. -

1 Bruce Fein Answers Sri Lanka-Patton Boggs

Bruce Fein Answers Sri Lanka-Patton Boggs Monumental Deceits Joseph Goebbels, Adolph Hitler’s propagandist, would have advised lobbyists representing pariah countries like Sri Lank to parrot his tactics for defending Nazi Germany: “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it. The lie can be maintained only for such time as the State can shield the people from the political, economic, and/or military consequences of the lie. It thus becomes vitally important for the State to use all of its powers to repress dissent, for the truth is the mortal enemy of the lie, and thus by extension, the truth is the greatest enemy of the State.” The Sinhalese Buddhist Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) and its lobbying voice in the United States, Patton Boggs L.L.P., bettered the instruction of Goebbels in distributing a White Paper entitled “The Situation Today in Sri Lanka,” which omits any reference to the ongoing Srebrenica-like genocidal Tamil killings, maimings, and concentration camps by the GOSL in the northeast. Its sophomoric deceits challenge the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda’s most favorable spin on Auschwitz. Virtually every sentence in the GOSL-Patton Boggs propaganda is false or misleading by omission. As a concession to the shortness of life, this critique will be limited to the 10 most blatant lies or misrepresentations. 1. Statement: “The 26-year conflict with the terrorist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) is about to end.” Truth: The Sinhalese Buddhist GOSL has been employing violence and intimidation amounting to genocide against its Tamil civilian population since its birth in 1948, a span of 61 years. -

An Opinion Survey on the LLRC Report

0.1 Less Than Six Months 10 13.7 Less than One Year 15.7 In 1-2 Years 18.7 2-5 Years 20.1 More than 5 years 21.6 No Answer Don't Know/Not Sure An Opinion Survey on the LLRC Report Based on Views of some Witnesses of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission and the Participants in Awareness Workshops An Opinion Survey on the LLRC Report Based on Views of some Witnesses of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission and the Participants in Awareness Workshops Centre for Policy Alternatives ISBN: 978-955-4746-03-9 Printers: Globe Printing Works, Tel: +94 (11) 2689259 Design By: Kamaladevi Sasichandran This publication has been produced in partnership with the Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung für die Freiheit. The Foundation’s work focuses on the core values of freedom and responsibility. Through its projects FNF contribute to a world in which all people can live in freedom, human dignity and peace. The contents of this publication are the responsibility of the Centre for Policy Alternatives. The Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) is an independent, non- partisan organization that focuses primarily on issues of governance and conflict resolution. Formed in 1996 in the firm belief that the vital contribution of civil society to the public policy debate is in need of strengthening, CPA is committed to programmes of research and advocacy through which public policy is critiqued, alternatives identified and disseminated. Address : 24/2 28th Lane, off Flower Road, Colombo 7 Telephone : +94 (11) 2565304/5/6 Fax : +94 (11) 4714460 Web : www.cpalanka.org Email : [email protected] 2 CONTENTS Opinion Survey on the LLRC Report --------------------------------- 5 I. -

Media in Promoting Small Business in Sri Lanka, by AC Nielsen, February 2006

Enter-Growth/Final Report Feb 2006 Media in Promoting Small Business in Sri Lanka The Enterprise for Pro-poor Growth - Enter-Growth project Enter - Growth International Labour Organization Final Report February 2006 i Enter-Growth/Final Report Feb 2006 About Enter-Growth Enterprise for Pro-poor Growth, or Enter-Growth for short, is a project of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA), and the Ministry of Investment and Enterprise Development. Its goal is to contribute to pro-poor economic growth and quality employment for women and men, through an integrated programme for development of micro and small enterprises. The project design is based on extensive consultations with provincial and district stakeholders from the Government, the private sector – micro and small enterprises in particular -, and NGOs. It seeks to address issues that relate to: • The market access of micro and small enterprises; • The policy and regulatory environment for micro and small enterprise growth; • Enterprise culture – the way enterprise is perceived and valued in society. The project’s most basic assumption is that none of the constraints in these areas can be addressed without dialogue with and between the stakeholders in the districts, and that they need to take the lead in finding and implementing solutions. Enter-Growth’s role is that of a facilitator in this process. After a first project concept in 2003, and a final document in 2004, the project started in June 2005, for a period of 3 years. It has a head office in Colombo, and offices in each of the four Districts covered.