Journalism Training and Research in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Stations

1 CHANGING STATIONS FULL INDEX 100 Top Tunes 190 2GZ Junior Country Service Club 128 1029 Hot Tomato 170, 432 2HD 30, 81, 120–1, 162, 178, 182, 190, 192, 106.9 Hill FM 92, 428 247, 258, 295, 352, 364, 370, 378, 423 2HD Radio Players 213 2AD 163, 259, 425, 568 2KM 251, 323, 426, 431 2AY 127, 205, 423 2KO 30, 81, 90, 120, 132, 176, 227, 255, 264, 2BE 9, 169, 423 266, 342, 366, 424 2BH 92, 146, 177, 201, 425 2KY 18, 37, 54, 133, 135, 140, 154, 168, 189, 2BL 6, 203, 323, 345, 385 198–9, 216, 221, 224, 232, 238, 247, 250–1, 2BS 6, 302–3, 364, 426 267, 274, 291, 295, 297–8, 302, 311, 316, 345, 2CA 25, 29, 60, 87, 89, 129, 146, 197, 245, 277, 354–7, 359–65, 370, 378, 385, 390, 399, 401– 295, 358, 370, 377, 424 2, 406, 412, 423 2CA Night Owls’ Club 2KY Swing Club 250 2CBA FM 197, 198 2LM 257, 423 2CC 74, 87, 98, 197, 205, 237, 403, 427 2LT 302, 427 2CH 16, 19, 21, 24, 29, 59, 110, 122, 124, 130, 2MBS-FM 75 136, 141, 144, 150, 156–7, 163, 168, 176–7, 2MG 268, 317, 403, 426 182, 184–7, 189, 192, 195–8, 200, 236, 238, 2MO 259, 318, 424 247, 253, 260, 263–4, 270, 274, 277, 286, 288, 2MW 121, 239, 426 319, 327, 358, 389, 411, 424 2NM 170, 426 2CHY 96 2NZ 68, 425 2Day-FM 84, 85, 89, 94, 113, 193, 240–1, 243– 2NZ Dramatic Club 217 4, 278, 281, 403, 412–13, 428, 433–6 2OO 74, 428 2DU 136, 179, 403, 425 2PK 403, 426 2FC 291–2, 355, 385 2QN 76–7, 256, 425 2GB 9–10, 14, 18, 29, 30–2, 49–50, 55–7, 59, 2RE 259, 427 61, 68–9, 84, 87, 95, 102–3, 107–8, 110–12, 2RG 142, 158, 262, 425 114–15, 120–2, 124–7, 129, 133, 136, 139–41, 2SM 54, 79, 84–5, 103, 119, 124, -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger -

South Bergen Fri Ends. Wish You a Happy '60 Leader

Ilttiem MdllUKMKOMW» South Bergen Fri ends. Wish You A Happy '60 ta t to. &x j « * s x ïsx «« ew b k a oilier in years nifi in ihf last week. They exrhaiiKed shame-faced .looks. Then thry l»f((an Leader Publications to tell their »¿yfilu rr» of traveling by Im»*. They told iiorrrndoii« stori«*»* of the long COMERCIAL LEADER .jJc h i y> raiis«*cl wlient*\i*r a -light m ish ap jaiiini«*«! NORTH ARLINGTON LEADER traili«* on tli«* hifjhwaVH. ^ Then they got into tin* warm. smoofh-run- LEADER FREE PRESS nifi” rail «ars an«l wrr«* shot into llnlmkcit vi iili- f'ut fu>s_or feathers. l*fthlishc<| e\«*r\ Thur-day I*\ III«* (.ommen ial Leader Priming < «unpan) at 2">l Ridge Road. I.vndhiirst. Y J. Telephone t,fcneva A instant Railroads KTol W hen the storm broke la-t week, «lumping •more snow than we have experience«! in two Yes Virginia ? vear-. the railroails went into a«*tion at once. They put to work gangs of hiimlre«ls «»f men T«» tin* jiood little girl w ith tin* spit c u rl w ho clearing the way. warming up the switches and aske«l last week if tlitre really. really are pas- making r«*a«ly for wliat«*\cr tin* storm might s«*nger trains, the answer i« an «»mphatic yes. bring. On last ..Monday aftern«M»n snow began to The buses waited for the government to fall. By the time darkness f«*ll the snow he<ame «*l«*aii th e highw ays. -

PE 2020 MR 82 S.Pdf

Election Commission – Sri Lanka Parliamentary Election - 05.08.2020 Registered electronic media to disseminate certified election results Last Updated Online Social Media No Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites (FB/ SMS Paper Web Sites) YouTube/ Twitter) 1 Telshan Network TNL TV - - - - - (Pvt) Ltd 2 Smart Network - - - www.lankasri.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 3 Bhasha Lanka (Pvt) - - - www.helakuru.lk - - Ltd 4 Digital Content - - - www.citizen.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 5 Ceylon News - - www.mawbima.lk, - - - Papers (Pvt) Ltd www.ceylontoday.lk Independent ITN, Lakhanda, www.itntv.lk, ITN Sri Lanka 6 Television Network Vasantham TV Vasantham - www.itnnews.lk (FB) - Ltd FM Lakhanda Radio (FB) Sri Lanka City FM 7 Broadcasting - - - - - Corporation (SLBC) Asia Broadcasting Hiru FM. 8 Corparation Hiru TV Shaa FM, www.hirunews.lk, Sooriyan FM, - www.hirugossip.lk - - Sun FM, Gold FM 9 Asset Radio Broadcasting (Pvt) - Neth FM - www.nethnews.lk NethFM(FB) - Ltd 1/4 File Online Number Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites Social Media SMS Paper Web Sites) Asian Media 10 Publications (Pvt) ltd - - www.thinakkural.lk - - - 11 EAP Broadcasting Swarnavahini Shree FM, - www.swarnavahini.lk, - - Company Ran FM www.athavannews.com 12 Voice of Asia Siyatha TV Siyatha FM - - - - Network (Pvt)Ltd Star tamil TV MTV Channel (Pvt) Sirasa TV, Sirasa FM, News 1st (FB), News 1st SMS 13 Ltd / MBC Shakthi TV, Shakthi FM, News 1st (S,T,E), Networks (Pvt) Ltd TV1 Yes FM, - www.newsfirst.lk (Youtube), KIKI mobile YFM, News 1st App Legends FM (Twitter) -

Family Planning in Ceylon1

1 [This book chapter authored by Shelton Upatissa Kodikara, was transcribed by Dr. Sachi Sri Kantha, Tokyo, from the original text for digital preservation, on July 20, 2021.] FAMILY PLANNING IN CEYLON1 by S.U. Kodikara Chapter in: The Politics of Family Planning in the Third World, edited by T.E.Smith, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1973, pp 291-334. Note by Sachi: I provide foot note 1, at the beginning, as it appears in the published form. The remaining foot notes 2 – 235 are transcribed at the end of the article. The dots and words in italics, that appear in the text are as in the original. No deletions are made during transcription. Three tables which accompany the article are scanned separately and provided. Table 1: Ceylon: population growth, 1871-1971. Table 2: National Family Planning Programme: number of clinics and clinic-population ratio by Superintendent of Health Service (SHS) Area, 1968-9. Table 3: Ceylon: births, deaths and natural increase per 1000 persons living, by ethnic group. The Table numbers in the scans, appear as they are published in the book; Table XII, Table XIII and Table XIV. These are NOT altered in the transcribed text. Foot Note 1: In this chapter the following abbreviations are used: FPA, Family 2 Planning Association, LSSP, Lanka Samasamaja Party, MOH, Medical Officer of Health, SLFP, Sri Lanka Freedom Party; SHS, Superintendent of Health Services; UNP, United National Party. Article Proper The population of Ceylon has grown rapidly over the last 100 years, increasing more than four-fold between 1871 and 1971. -

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert PhD 2016 Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Politics and Philosophy Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 Abstract: The thesis argues that the telephone had a significant impact upon colonial society in Sri Lanka. In the emergence and expansion of a telephone network two phases can be distinguished: in the first phase (1880-1914), the government began to construct telephone networks in Colombo and other major towns, and built trunk lines between them. Simultaneously, planters began to establish and run local telephone networks in the planting districts. In this initial period, Sri Lanka’s emerging telephone network owed its construction, financing and running mostly to the planting community. The telephone was a ‘tool of the Empire’ only in the sense that the government eventually joined forces with the influential planting and commercial communities, including many members of the indigenous elite, who had demanded telephone services for their own purposes. However, during the second phase (1919-1939), as more and more telephone networks emerged in the planting districts, government became more proactive in the construction of an island-wide telephone network, which then reflected colonial hierarchies and power structures. Finally in 1935, Sri Lanka was connected to the Empire’s international telephone network. One of the core challenges for this pioneer work is of methodological nature: a telephone call leaves no written or oral source behind. -

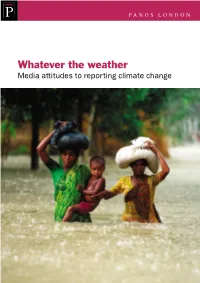

6. Whatever the Weather. Media Attitudes to Reporting Climate Change

PANOS LONDON Whatever the weather Media attitudes to reporting climate change Contents 1 Climate change and the media 1 Global policy on climate change 2 Carbon trading standards 3 The survey 4 Key findings 4 Recommendations 6 2 Case studies 7 Honduras 7 Jamaica 10 Sri Lanka 12 Zambia 14 Cover: © Panos London, 2006 Villagers returning with relief aid through heavy rains. Monsoon Panos London is part of a worldwide rains caused flooding in 40 network of independent NGOs working of Bangladesh’s 64 districts, displacing up to 30 million people with the media to stimulate debate and killing several hundred. on global development. GMB AKASH/PANOS PICTURES All photographs available from Panos Pictures www.panos.co.uk For further information contact: Environment Programme Written by Rod Harbinson with Panos London case studies by Dr Richard Mugara 9 White Lion Street (Zambia) and Ambika Chawla London N1 9PD (Sri Lanka, Jamaica and Honduras). United Kingdom Thanks to Panos Caribbean and Panos Southern Africa for Tel: +44(0)20 7278 1111 their contribution. Fax: +44(0)20 7278 0345 Designed by John F McGill [email protected] Printed by Digital-Brookdale www.panos.org.uk/environment Whatever the weather: media attitudes to reporting climate change 1 Climate change and the media 1 YOLA MONAKHOV/PANOS PICTURES The media play an important role in stimulating discussion in developing countries. Yet journalists asked by Panos say that the media have a poor understanding of the climate change debate and express little interest in it. Public discussion of the policies and issues involved is urgently needed. -

State Electronic Media During the Parliamentary Elections of October 2000

REPORT ON THE PERFORMANCE OF THE NON- STATE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DURING THE PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS OF OCTOBER 2000 Preface This Report on the Performance of the Non- State Electronic Media During the Parliamentary Elections of October 2000 is the counterpart of the Report by INFORM on The Publicly Funded Electronic Media. The Reports were prepared in collaboration with Article 19 and with the generous assistance of NORAD, The Asia Foundation and the Royal Netherlands Embassy. The issue of media performance at the time of elections is an extremely pertinent one for a variety of reasons. Of especial importance is the division within Sri Lanka between state and non-state media and the impact this has on the performance of the media during election time. Issues of agenda setting, partisan bias and stereotype invariably surface and in turn confirm that partisan allegiance characterizes media in Sri Lankan irrespective of type of ownership and management. Consequently, the role of the media in helping citizens to make informed choices at elections is seriously diminished and the need for greater professionalism in the media reinforced. This Report highlights these issues through an analysis of election reportage. It concludes with a set of recommendations which have been classified into the mandatory and the voluntary. CPA believes that the issue of media reportage at election times is integral to strengthening the institutions of a functioning democracy in Sri Lanka and of fundamental importance in enhancing the contribution of civil society to better governance. This Report, its conclusions and recommendations are presented in this spirit and in the hope that electronic media reportage at election time can develop in the near future, into an example of media best practice in Sri Lanka. -

The Sri Lankan Insurgency: a Rebalancing of the Orthodox Position

THE SRI LANKAN INSURGENCY: A REBALANCING OF THE ORTHODOX POSITION A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Peter Stafford Roberts Department of Politics and History, Brunel University April 2016 Abstract The insurgency in Sri Lanka between the early 1980s and 2009 is the topic of this study, one that is of great interest to scholars studying war in the modern era. It is an example of a revolutionary war in which the total defeat of the insurgents was a decisive conclusion, achieved without allowing them any form of political access to governance over the disputed territory after the conflict. Current literature on the conflict examines it from a single (government) viewpoint – deriving false conclusions as a result. This research integrates exciting new evidence from the Tamil (insurgent) side and as such is the first balanced, comprehensive account of the conflict. The resultant history allows readers to re- frame the key variables that determined the outcome, concluding that the leadership and decision-making dynamic within the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had far greater impact than has previously been allowed for. The new evidence takes the form of interviews with participants from both sides of the conflict, Sri Lankan military documentation, foreign intelligence assessments and diplomatic communiqués between governments, referencing these against the current literature on counter-insurgency, notably the social-institutional study of insurgencies by Paul Staniland. It concludes that orthodox views of the conflict need to be reshaped into a new methodology that focuses on leadership performance and away from a timeline based on periods of major combat. -

TITLE a Report on the Activities of the First Five Years, 1963-1968

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 827 AC 008 547 TITLE A Report on the Activities of the First Five Years, 1963-1968. INSTITUTION Thompson Foundation, London (England). PUB DATE [69] NOTE 34p.; photos EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$1.80 DESCRIPTORS Admission Criteria, Audiovisual Aids, Capital Outlay (for Fixed Assets), Curriculum, Developing Nations, Expenditure Per Student, Foreign Nationals, Grants, *Inservice Education, Instructional Staff, *Journalism, Physical Facilities, *Production Techniques, Students, *Television IDENTIFIERS Great Britain ABSTRACT The Thomson Foundation trains journalists and television producers and engineers from developing nations in order to help these nations use mass communication techniques in education. Applicants must be fluent in English; moreover, their employers must certify that the applicants merit overseas training and will return to their work after training. Scholarships cover most expenses other than travel to and from the United Kingdom. Three 12-week courses covering such topics as news editing, reporting, features, photography, agricultural journalism, management, and press freedoms, are held annually at the Thomson Foundation Editorial Study Centre in Cardiff; two 16-week courses are held on various aspects of engineering and program production at the Television College, Glasgow. During vacation periods, the centers offer workshops and other inservice training opportunities to outside groups.(The document includes the evolution of the programs, trustee and staff rosters, Foundation grants, capital and per capita costs, overseas visits and cumulative list of students from 68 countries.) (LY) A REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE FIRST FIVE YEARS 1963/1968 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. -

Proceedings of 8Th International Symposium-2018, SEUSL

Proceedings of 8th International Symposium-2018, SEUSL THE DEPICTION OF CLOTHING FASHION IN PRINT MEDIA Sulari De Silva Department of Textile & Clothing Technology, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka [email protected] ABSTRACT: The mass media is one of the most influential sources on fashion today; the influence is complex and diverse. Throughout the last century, in Sri Lanka, the print media have become an opinion leader of fashion and played a vital role in shaping ‘fashion’ into a complex social and cultural phenomenon. Thus, as both an art form and a commercial enterprise ‘fashion’ has begun to depend upon attention in media. This study analyses the relationship between print media and popular fashion in Sri Lanka, providing a historical overview from the beginning of print media to discuss their specific orientation towards fashion coverage. Today, newspapers and magazines - the print media in Sri Lanka, as a form of traditional media, work in a different contextual structure of fashion coverage and their function is more of a commercial nature which largely depends on advertising. The shift of fashion models from being product-centric to being consumer-centric is evident in the recent past as newspapers and magazines are losing ground in favour of electronic media and of online communication media. However there are number of newspapers and magazines exist today in many different forms and genres the country has no highly developed media system, with extremely elevated levels of media-usage. This study demonstrates the relationship between print media and fashion in Sri Lanka under three phases. The first phase is the era of the beginning of print media in the country.