Teaching Literacy Through the Visual Arts: from Filmic to Textual Rhetoric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Muppets Take the Mcu

THE MUPPETS TAKE THE MCU by Nathan Alderman 100% unauthorized. Written for fun, not money. Please don't sue. 1. THE MUPPET STUDIOS LOGO A parody of Marvel Studios' intro. As the fanfare -- whistled, as if by Walter -- crescendos, we hear STATLER (V.O.) Well, we can go home now. WALDORF (V.O.) But the movie's just starting! STATLER (V.O.) Yeah, but we've already seen the best part! WALDORF (V.O.) I thought the best part was the end credits! They CHORTLE as the credits FADE TO BLACK A familiar voice -- one we've heard many times before, and will hear again later in the movie... MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) And lo, there came a day like no other, when the unlikeliest of heroes united to face a challenge greater than they could possibly imagine... STATLER (V.O.) Being entertaining? WALDORF (V.O.) Keeping us awake? MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) Look, do you guys mind? I'm foreshadowing here. Ahem. Greater than they could possibly imagine... CUT TO: 2. THE MUPPET SHOW COMIC BOOK By Roger Langridge. WALTER reads it, whistling the Marvel Studios theme to himself, until KERMIT All right, is everybody ready for the big pitch meeting? INT. MUPPET STUDIOS The shout startles Walter, who tips over backwards in his chair out of frame, revealing KERMIT THE FROG, emerging from his office into the central space of Muppet Studios. The offices are dated, a little shabby, but they've been thoroughly Muppetized into a wacky, cozy, creative space. SCOOTER appears at Kermit's side, and we follow them through the office. -

A BUG's LIFE the Muppets

TheA BUG’S Muppets LIFE Synopsis On vacation in Los Angeles, Walter, the world’s biggest Muppet fan, his brother Gary and Gary’s girlfriend, Mary, from Smalltown, USA, discover the nefarious plan of oilman Tex Richman to raze Muppet Studios and drill for the oil recently discovered beneath the Muppets’ former stomping grounds. To stage a telethon and raise the $10 million needed to save the studio, Walter, Mary and Gary help Kermit reunite the Muppets, who have all gone their separate ways: Fozzie now performs with a Reno casino tribute band called the Moopets, Miss Piggy is a plus-size fashion editor at Vogue Paris, Animal is in a Santa Bar- bara clinic for anger management, and Gonzo is a high-powered plumbing magnate. Discussion Questions • Gary and Walter are brothers, even though Gary is a person and Walter is a Muppet. Do you think it would have been hard growing up together and being so different, particularly as Walter is never any taller on the wall chart they keep at their home? • Toward the end of the film there is a key song that involves Gary and Walter. What do you think they are singing about when they mention being a man or being a Muppet? How do you think they end up realizing and embracing their true identities? • Gary tells Walter that the point of growing up is to be whoever or whatever you want to be. Who do you want to be? What kind of person do you want to be? Is that the same as what profession you want to have when you grow up? • There is a character in the film who is an executive for the television station. -

“The Muppets” Road Trip Game

Are we there yet? How ‘bout now? Now? How about now? Those questions can only mean one thing: road trip! (With children.) And Kermit knows road trips! In the upcoming film Disney’s “The Muppets,” Kermit joins Walter (Walter), Gary (Jason Segel), Mary (Amy Adams) and—eventually—the whole Muppet gang in the car for a trip of their own, as they endeavor to save Muppet Studios from evil oilman Tex Richman. So don’t despair. The Muppets can help keep kids busy and happy with… DISNEY’S “THE MUPPETS” ROAD TRIP GAME See if you can spot: 5 Kermit green cars 1 Person who looks like a relative of Gonzo’s 3 People who look like they just stepped off the Electric Mayhem Band bus 4 of Miss Piggy’s biggest fans. How can you tell? Easy, they could be a) Singing to themselves b) Fixing their hair in the mirror c) Blowing kisses to you through the window d) Blowing kisses to themselves in the mirror 2 Bumper stickers that are so funny, Fozzie Bear would add them to his act 4 People wearing suits they stole from Statler and Waldorf 3 Cars that are so patriotic, Sam the Eagle just might be driving them Bonus: Sing the chorus of “Mahna Mahna” or “Rainbow Connection” at a red light or while driving through a tunnel Find a license plate from Smalltown, USA (or at least one that is red, white and blue) Find the letters of Disney’s “The Muppets” in license plates. -

Oral History Interview with Walter Midener, 1981 Aug. 3

Oral history interview with Walter Midener, 1981 Aug. 3 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Walter and Peggy Midener on August 3, 1981. The interview took place in East Jordan, Michigan and was conducted by Dennis Barrie for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The Archives of American Art has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview DENNIS BARRIE: This is usually a pretty reliable machine. You can all talk. Why don't you all say something? Just say who you are. PEGGY MIDENER: Hi, I'm— DENNIS BARRIE: I just want to see if it's picking you up. PEGGY MIDENER: I'm Peggy Midener, the missing [laughs]— DENNIS BARRIE: The missing link. PEGGY MIDENER: Right, in the previous interview. DENNIS BARRIE: Walter, say something. Let me just see if we're recording. WALTER MIDENER: We are going to—our last interview was in 1874, and—no [they laugh], 1974 [Audio Break.] DENNIS BARRIE: Okay. It is the third of August, 1981. I am in—is this technically East Jordan? PEGGY MIDENER: Yes. -

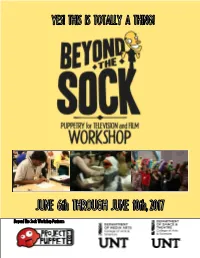

Beyond the Sock Workshop Partners: There’S a Method to Our Madness

Beyond The Sock Workshop Partners: There’s A Method To Our Madness. Beyond the Sock is an intensive, five day workshop focusing on puppetry performance in television and film. Attendees have the unique opportunity to learn the manipulation of hand and rod style puppets from two of the top performers in the industry, Peter Linz and Noel MacNeal. Attendees also learn the art of design and construction from master puppet builder Pasha Romanowski. Through a blend of small group instruction and hands on training puppet builders and performers of all skill levels can develop their skills, discover new techniques and learn to craft their own characters. Don’t miss the unique opportunity! Registration and Attendance Fees General Registration: Includes performance and building sessions, puppet building materials and welcome reception. Please note that all general $1400.00 registration attendees must pre-register. Student Registration: Must be a currently enrolled college or university student in good standing. Must provide proof of enrollment and $850.00 letter of recommendation. Contact us for more details. Student attendees Must be at least 18 years of age. Ready to get in on the action? All registrations must be completed electronically using a valid credit or debit card. Simply visit us online at www.beyondthesock.com at www.beyondthesock.unt.edu or sing up via direct link on our event registration page found at https://beyondthesock.eventbrite.com. Our class size is limited in order to maximize the experience for our attendees. Register today! WORKSHOP DATES: JUNE 6th through JUNE 10th, 2017 NEED MORE INFO? EMAIL: [email protected] Our Instructors Are Among The Best In The Business! Performance Instructors Peter Linz is a professional puppet performer who has performed in film, theatre and television using both hand-and-rod and full-body puppets. -

Pasta & Puddles

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U OPEN HOUSES, A4 • TRIBUTES, A7 • WORLD, A8 • BUSINESS, A10 • CLASSIFIEDS, B5 • OUTDOORS, B7 • RELIGION, B8 • TV WEEK POLAND GIRLS PLAY FOR IT ALL ILLEGAL GAMBLING GET YOURSELF CHECKED OUT ESPN2 to carry game today Boardman probe brings 4 arrests Wellness walk next week SPORTS | B1 LOCAL | A3 ERNIE BROWN JR. | A2 FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 SATURDAY, AUGUST 5, 2017 U 75¢ FRANK WATSON, 92 WASHINGTON Wet weather fails to dampen appetite Community for Greater Youngstown Italian Festival Sessions vows leader, YSU to lower boom benefactor Pasta & puddles on leakers of mourned classifi ed info By AMANDA TONOLI and KALEA HALL Criminal probes triple [email protected] YOUNGSTOWN in Trump’s early months After a 10-year battle Associated Press with Parkinson’s disease, WASHINGTON Frank Charles Watson – also Attorney General Jeff Sessions known as “Dude” – died at pledged Friday to rein in government age 92 Thursday at his Can- leaks that he said undermine Ameri- fi eld home. can security, taking an aggressive pub- Watson, lic stand after being called weak on a lover and the matter by President graduate of Donald Trump. The nation’s top Youngstown law-enforcement of- State Univer- ficial cited no current sity, a phi- investigations in which lanthropist, disclosures of informa- family man Watson tion had jeopardized and local the country, but said leader, wore the number of criminal Sessions TRIBUTE his hard- ON PAGE A7 leak probes had more U working de- than tripled in the early INSIDE: Is meanor and months of the Trump the U.S. -

Fall Family Day Highlights Jim Henson and Puppetry with a Live Comedy Concert, Hands-On Workshops, and ‘The Muppets’ on the Big Screen

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FALL FAMILY DAY HIGHLIGHTS JIM HENSON AND PUPPETRY WITH A LIVE COMEDY CONCERT, HANDS-ON WORKSHOPS, AND ‘THE MUPPETS’ ON THE BIG SCREEN Free admission for youth ages 17 and under Saturday, October 14, 2017, 11:00 to 4:00 p.m. Astoria, Queens, New York, October 3, 2017—On Saturday, October 14, from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., families are invited to visit for a day centered around the new Jim Henson Exhibition packed with fun and educational experiences for children of all ages. At Fall Family Day, visitors will be immersed in the world of puppetry through hands-on puppet making and media creation in the Moving Image Studio, tours of the Henson Exhibition, drop-in screenings of “Muppet Family Moments,” and opportunities to attend Leslie and Lolly Make Stuff Up, a live interactive puppet show presented by Sesame Street performer Leslie Carrara-Rudolph, and a big-screen showing of The Muppets in the Redstone Theater. All programs are included below and online at movingimage.us/familyday For Fall Family Day, Museum admission will be FREE for youth ages 17 and under between 11:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. (Children under 14 must be accompanied by an adult.) Admission for adults is $15 ($11 for senior citizens and students). Please note: Ticket purchase is required for the live concert and screening of The Muppets. Puppet making and more in the Moving Image Studio 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. (Digital Learning Suite) Recommended for ages 4 and older. -

The Muppets with a Headline That Reads “Who’S the Funniest Muppet.” There Is Also a Row of Framed Photos, the First Is of a Young Boy with a Nondescript Brown Puppet

The Greatest Muppet Movie of All Time by Jason Segel and Nicholas Stoller 10-30-09 TITLE UP: THE FOLLOWING IS BASED ON A TRUE STORY FADE IN: A series of shots of a pristine, classic American small town. Something straight out of Pleasantville. --People walk down the street and say smiling goodmornings as they pass each other. --A milkman drops off milk to a white picket fenced house --Children ride their bikes to school -- People exit a bakery with fresh rolls. TITLE UP: SMALLTOWN, USA INT. BEDROOM - MORNING We pan through a bedroom who’s walls are covered with posters. Muppet posters. Muppet newspaper clippings. A framed photo of a Time magazine cover which features Kermit standing in front of the rest of the Muppets with a headline that reads “Who’s the funniest Muppet.” There is also a row of framed photos, the first is of a young boy with a nondescript brown Puppet. We follow the row of photos as the boy grows progressively older, his puppet always by his side, ageless. We reach the last photo of the row and the boy is now thirty, arm around his puppet. We continue to pan and find the man, Gary, laying in bed peacefully asleep, a contented smile on his face. THE ALARM GOES OFF. Gary lazily wakes up. GARY Walter! Wake up! Today’s the day we go to Los Angeles!!! We widen to reveal Gary’s brown puppet asleep in a smaller bed next to Gary ala Ernie and Bert. WALTER (waking excitedly) Los Angeles!!! I can’t believe it!! We’re gonna get to go to Muppet Studios right!? You promised!? You weren’t pranking me right!!? If you were pranking me that’s a really mean prank!!! 2. -

In This Issue the Structure Consists of Nanometers, the Diameter of in Addition to Its Ultra- Torrents and Lorenzo Valdevit 99.99% Open Volume

The California Tech [email protected] VOLUME CXV NUMBER 9 PASADENA , CALIFORNIA TE C H .C ALTE C H .EDU NO V EMBER 21, 2011 Caltech researchers create lightest solid material KIMM FESENMAIER The new material, called a LLC, and lead author on the centimeters (but might one day be as 50 percent, making it excellent at Science Writer micro-lattice, relies, appropriately, report described it as “a lattice of made meters in length). absorbing energy. on a lattice architecture: tiny hollow interconnected hollow tubes with a Just as with large-scale “The emergence of the unique When you pick up the newest tubes made of nickel-phosphorous wall thickness of 100 nanometers, structures, such as the Eiffel Tower, properties of these ultra-light material in Julia Greer’s micro-lattice structures office, it takes a second is due, in part, to the for your mind to adjust. different mechanical Despite its looks, the little behavior that emerges brick of metal weighs in nano-sized solids, next to nothing. which is the focus of my Greer, assistant research,” Greer says. professor of materials Her team uses science and mechanics, a machine called a is part of a team of SEMentor, which is both researchers from Caltech, an electron microscope HRL Laboratories, LLC, and a nanoindenter, to and the University of visualize the deformation California, Irvine, who of nano-sized structures have developed the and to concurrently world’s lightest solid measure mechanical material, with a density properties, such as how of just 0.9 milligrams much force it takes to per cubic centimeter, or break a material, how approximately 100 times much energy it can lighter than Styrofoam™. -

The Muppet Phenomenon in the United States Nicole B

William & Mary W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1999 "C" is for Cookie, Culture, and Capitalism: The Muppet Phenomenon in the United States Nicole B. Cloeren College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cloeren, Nicole B., ""C" is for Cookie, Culture, and Capitalism: The uM ppet Phenomenon in the United States" (1999). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626195. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-snyf-p828 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “C" IS FOR COOKIE, CULTURE, AND CAPITALISM The Muppet Phenomenon in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Nicole B. Cloeren 1999 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Nicole B. Cloeren Approved, April 1999 Kenneth M. Price Elizabeth A Theatre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My gratitude goes to my advisor and mentor, Arthur Knight, for all of his support, encouragement, and constructive criticism. Also to Ken Price and Ann Elizabeth Armstrong for their suggestions and guidance. -

LEADER-THESIS.Pdf (1.353Mb)

Copyright by Caroline Ferris Leader 2011 The Thesis Committee for Caroline Ferris Leader Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The lovers and dreamers go corporate: Re-authoring Jim Henson’s Muppets under Disney APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: (Thomas G. Schatz) (Mary Celeste Kearney) The lovers and dreamers go corporate: Re-authoring Jim Henson’s Muppets under Disney by Caroline Ferris Leader, BA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To my parents, who taught their children to be imaginative and hard working, and who introduced me to Jim Henson’s work. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor and reader, Thomas G. Schatz and Mary Celeste Kearney, for their invaluable role in facilitating my research and writing process. Their knowledge and experience has inspired me to push myself beyond my own expectations. I would also like to thank my colleagues and friends, especially Charlotte Howell, who for the last 18 months kept me up to date on all Muppet-related news on the Web. These people will always be more connected to current pop culture trends than I am, so I am grateful that they took the time to keep me in the loop. v Abstract The lovers and dreamers go corporate: Re-authoring Jim Henson’s Muppets under Disney Caroline Ferris Leader, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Thomas G. -

BOREDOM BUSTERS to CELEBRATE PWS MAY AWARENESS • WEEK 1 • 25 PAGES of FUN! PWS on the Move Games and FUN!

PRESENTS BOREDOM BUSTERS TO CELEBRATE PWS MAY AWARENESS • WEEK 1 • 25 PAGES OF FUN! PWS On The Move Games and FUN! ....................... Section 1 Games and Activity Sheets .......................................... Section 2 I Spy ...................................................................................... Section 3 Word Searches ................................................................. Section 4 Coloring Pages ................................................................ Section 5 FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY SECTION 1 PWS On The Move Games and FUN! WACKYWACKY WALKWALK WACKYWACKY WALKWALK WACKYWACKY WALKWALK A Walk Like an Animal A Walk Like an Animal A Walk Like an Animal 2 Skip to my lou 2 Skip to my lou 2 Skip to my lou 3 High knees 3 High knees 3 High knees 4 Forward no more 4 Forward no more 4 Forward no more 5 Dance a jive 5 Dance a jive 5 Dance a jive 6 Mix it up 6 Mix it up 6 Mix it up 7 Singing time 7 Singing time 7 Singing time 8 Don’t be late (jog) 8 Don’t be late (jog) 8 Don’t be late (jog) 9 Avoid the lines 9 Avoid the lines 9 Avoid the lines 10 Take your time 10 Take your time 10 Take your time J Everybody jump J Everybody jump J Everybody jump Q Walk quietly Q Walk quietly Q Walk quietly K Kick it out K Kick it out K Kick it out WACKYWACKY WALKWALK WACKYWACKY WALKWALK WACKYWACKY WALKWALK WACKYWACKY WALKWALK A WACKYWACKYWalk Like an Animal WALKWALK A WACKYWACKYWalk Like an Animal WALKWALK A Walk Like an Animal A Walk Like an Animal 2 SkipA Walkto my Like lou an Animal 2 SkipA Walkto my Like lou an Animal 2 Skip to my lou 2 Skip to my lou 3 High2 Skipknees to my lou 3 High2 Skipknees to my lou 3 High knees 3 High knees 4 Forward3 High no knees more 4 Forward3 High no knees more 4 Forward no more Let’s4 Forward Playno more Wacky5 Dance4 Forward aWalk! jive no more 5 Dance4 Forward a jive no more 5 Dance a jive 5 Dance a jive 6 Mix5 itDance up a jive 6 Mix5 itDance up a jive 6 Mix it up 1.