1 the Chianti Five

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:50:30Z !

Title Corporeal prisons: dynamics of body and mise-en-scène in three films by Paul Schrader Author(s) Murphy, Ian Publication date 2015 Original citation Murphy, I. 2015. Corporeal prisons: dynamics of body and mise-en- scène in three films by Paul Schrader. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2015, Ian Murphy. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/2086 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T05:50:30Z ! Corporeal Prisons: Dynamics of Body and Mise-en-Scène in Three Films by Paul Schrader ! ! ! ! Dissertation submitted in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of English, College of Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Sciences, National University of Ireland, Cork By Ian Murphy Under the Supervision of Doctor Gwenda Young Head of School: Professor Claire Connolly January 2015 Table of Contents Declaration 3 Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER ONE Man in a Room: Male Anxiety and Mise-en-Scène in American Gigolo (1980) 26 CHAPTER TWO Beauty in the Beast: The Monstrous-Feminine and Masculine Projection in Cat People (1982) 88 CHAPTER THREE The Closed Crystal: Autoerotic Desire and the Prison of Narcissism in Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985) 145 CONCLUSION 209 WORKS CITED 217 ! 2! Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and it has not been submitted for another degree, either at University College Cork or elsewhere. ___________________________________________ Ian Murphy ! 3! Abstract This thesis focuses on the complex relationship between representations of the human body and the formal processes of mise-en-scène in three consecutive films by the writer-director Paul Schrader: American Gigolo (1980), Cat People (1982) and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985). -

Cashbox Pands in Publishing • • Atlantic Sees Confab Sales Peak** 1St Buddah Meet

' Commonwealth United’s 2-Part Blueprint: Buy Labels & Publishers ••• Massler Sets Unit For June 22 1968 Kiddie Film ™ ' Features * * * Artists Hit • * * Sound-A-Like Jingl Mercury Ex- iff CashBox pands In Publishing • • Atlantic Sees Confab Sales Peak** 1st Buddah Meet Equals ‘ Begins Pg. 51 RICHARD HARRIS: HE FOUND THE RECIPE Int’l. Section Take a great lyric with a strong beat. Add a voice and style with magic in it. Play it to the saturation level on good music stations Then if it’s really got it, the Top-40 play starts and it starts climbingthe singles charts and selling like a hit. And that’s exactly what Andy’s got with his new single.. «, HONEY Sweet Memories4-44527 ANDY WILLIAMS INCLUDING: THEME FROM "VALLEY OF ^ THE DOLLS" ^ BYTHETIME [A I GETTO PHOENIX ! SCARBOROUGH FAIR LOVE IS BLUE UP UPAND AWAY t THE IMPOSSIBLE * DREAM if His new album has all that Williams magic too. Andy Williams on COLUMBIA RECORDS® *Also available fn A-LikKafia 8-track stereo tape cartridges : VOL. XXIX—Number 47/June 22, 1968 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone: JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box. N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President LEON SCHUSTER Treasurer IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL TOM McENTEE Assoc. Editor DANIEL BOTTSTEIN JOHN KLEIN MARV GOODMAN EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI When Tragedy Cries (hit ANTHONY LANZETTA ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER New York For 'Affirmative'Musif BILL STUPER New York HARVEY GELLER Hollywood WOODY HARDING Art Director COIN MACHINES & VENDING ED ADLUM General Manager BEN JONES Asst. -

Cabinet Member Report

Cabinet Member Report Decision Maker: Cabinet Member for Business, Culture and Heritage Date: 26 September 2017 Classification: For General Release Title: Commemorative Green Plaque for Gold Brothers’ Lord John boutique, at 43 Carnaby Street , W1 Wards Affected: West End Key Decision: No Financial Summary: The Green Plaque Scheme depends on sponsorship. Sponsorship has been secured for this plaque Report of: Head of City Promotions, Events & Filming 1. Executive Summary The Lord John Boutique was opened in Carnaby Street by the brothers Warren and David Gold in 1963. It was one of the first retail brands in menswear and the shop was instantly a huge success and a major reason why Carnaby Street became world famous. The street continues to be a major Westminster attraction today. 2. Recommendations That the nomination for a Westminster Commemorative Green Plaque for the Gold Brothers’ Lord John boutique at 43 Carnaby Street, W1, be approved, subject to sponsorship in full. 3. Reasons for decision With his brother David, Warren Gold founded the influential national chain Lord John in 1963 after having worked on market stalls in east London. Through their foresight and extraordinary vision the Gold brothers revolutionised fashion and 1 became leading pioneers in the menswear industry. The brothers worked together for more than 50 years until David’s death in 2009. 4. Policy Context The commemorative Green Plaques scheme complements a number of Council strategies: to improve the legibility and understanding of Westminster’s heritage and social history; to provide information for Westminster’s visitors; to provide imaginative and accessible educational tools to raise awareness and understanding of local areas, particularly for young people; to celebrate the richness and diversity of Westminster’s former residents. -

Movie Museum AUGUST 2016 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum AUGUST 2016 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY 2 Hawaii Premieres! Hawaii Premiere! LA BOUM SING STREET BAREFOOT GEN THE LAST DIAMOND DR. AKAGI aka The Party (2016-Ireland/UK/US) (1983-Japan) aka Le dernier diamant (1998-Japan) (1980-France) in widescreen animation, subtitled, ws (2014-France/Luxem/Belg) Japanese w/Eng subtitles, ws 11:00am only Directed by Shôhei Imamura French w/Eng subtitles, ws with Ferdia Walsh-Peelo French w/Eng subtitles, ws --------------------------------- 11:15am, 1:30, 3:45, 9:00pm with Sophie Marceau. Directed by John Carney with Bérénice Bejo 2 Hawaii Premieres! --------------------------------- 11am, 3 & 7pm 11am, 3 & 7pm 11:30am & 6:45pm ---------------------------------- BAREFOOT GEN 2 BAREFOOT GEN ---------------------------------- (1986-Japan) ---------------------------------- Hawaii Premiere! (1983-Japan) THE LAST DIAMOND 12:30pm only LAST DAYS IN THE 6:00pm only aka Le dernier diamant LA BOUM --------------------------------- DESERT --------------------------------- (2014-France/Luxem/Belg) aka The Party STATION aka Eki (2015-US) Hawaii Premiere! French w/Eng subtitles, ws (1980-France) (1981-Japan) in widescreen BAREFOOT GEN 2 with Yvan Attal. French w/Eng subtitles, ws Japanese w/Eng subtitles, ws with Ewan McGregor. (1986-Japan) 1, 5 & 9pm 4 1, 5 & 9pm 5 2:00, 4:15, 6:30, 8:45pm 6 1:30, 3:15, 5:00, 8:45pm 7 7:30pm only 8 3 Hawaii Premieres! 2 Hawaii Premieres! 3 Hawaii Premieres! A HOLOGRAM FOR MARGUERITE STATION aka Eki DAREDEVIL IN THE (2015-France/Czech/Belgium) -

The East Bay Historia I 2017

The East Bay Historia California State University, East Bay's History Department Journal Volume 1, 2017 The East Bay Historia THE EAST BAY HISTORIA Volume 1: 2017 California State University, East Bay Journal of History The annual publication of the Student Historical Society and the Department of History California State University, East Bay "If you have the feeling that something is wrong, don’t be afraid to speak up." -Fred Korematsu The East Bay Historia This issue of The East Bay Historia is dedicated to Fred T. Korematsu And the hundreds of thousands of others of Japanese ancestry, many of whom lived on the West Coast and in the San Francisco Bay Area, who were torn from their homes and families due to the signing of Executive Order #9066 in 1942. 2017 marks the 75th anniversary of this tragedy. May we never forget. viii The East Bay Historia History Department California State University, East Bay 25800 Carlos Bee Boulevard Student and Faculty Services, Room 442 Hayward, California, 94542 (510) 885-3207 The East Bay Historia is an annual publication of the California State University, East Bay (CSUEB) Student Historical Society, and is sponsored by the History Department, Student Life and Leadership, and Associated Students, Inc. It aims to provide CSUEB students with an opportunity to publish historical works and to give students the experience of being on an editorial board and creating and designing an academic journal. Issues are published at the end of each academic year. All opinions or statements of fact are the sole responsibility of their authors, and may not reflect the views of the editorial staff, the Student Historical Society, the History Department, or California State University, East Bay (CSUEB). -

'We Are the Mods': a Transnational History of a Youth Culture

“‘We are the Mods’: A Transnational History of a Youth Culture” by Christine Jacqueline Feldman B.A., Western Washington University, 1993 M.A., Georgetown University, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Christine Jacqueline Feldman It was defended on January 6, 2009 and approved by Brent Malin, Assistant Professor, Communication Jane Feuer, Professor, English and Communication Sabine von Dirke, Associate Professor, Germanic Languages and Literatures Akiko Hashimoto, Associate Professor, Sociology Dissertation Advisor: Ronald J. Zboray, Professor, Communication ii Copyright © by Christine Jacqueline Feldman 2009 iii “‘WE ARE THE MODS’: A TRANSNATIONAL HISTORY OF A YOUTH CULTURE” Christine Jacqueline Feldman, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Mod youth culture began in the postwar era as way for young people to reconfigure modernity after the chaos of World War II. Through archival research, oral history interviews, and participant observation, this work traces Mod’s origins from dimly lit clubs of London’s Soho and street corners of the city’s East End in the early sixties, to contemporary, country-specific expressions today. By specifically examining Germany, Japan, and the U.S., alongside the U.K., I show how Mod played out in countries that both lost and won the War. The Mods’ process of refashioning modernity—inclusive of its gadgetry and unapologetic consumerism—contrasts with the more technologically skeptical and avowedly less materialistic Hippie culture of the later sixties. Each chapter, which unfolds chronologically, begins with a contemporary portrait of the Mod scene in a particular country, followed by an overview stretching back to its nineteenth- century conceptions of modernity and a section that describes Mod’s initial impact there during the 1960s. -

Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film Dedicated to the Memory of My Late Father, Paul R

Outlaw Masters Of Japanese Film Dedicated to the memory of my late father, Paul R. Desjardins, 1919–2003, who went through hell his last few years and was consequently unable to finish his own book on his pioneering work in electron microscopy (in the field of plant pathology). Also to my mother, Rosemary, who has had her own gauntlet to run in the last year and has managed to come out the other side. Both my parents have always been loyal, loving and there for me, never turning their backs on me during my extended period of raising hell. To my girl, Lynne Margulies, a truly great soulmate in all things, including the creative process. And to the memory of late director Kinji Fukasaku, a great inspiration to anyone daring to think of giving up in the face of adversity. I was lucky to get to know him and to consider him as a mentor as well as a friend. OUTLAW MASTERS OF JAPANESE FILM CHRIS D. Advisory Editor: Sheila Whitaker Published in 2005 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Chris Desjardins, 2005 The right of Chris Desjardins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

WALK the REVOLUTION! Drink As Well As Live Music

elcome to Sixties London: a place and time celebrated 02 V&A ‘Revolutions’ Shop, It also hosted veteran star bands including The Mothers of 11 Saville Theatre, 135 Shaftesbury Avenue in the latest major exhibition at the Victoria and 56a Carnaby Street Invention, Pink Floyd and The Who (who referred to the club on In 1965, Beatles manager Brian Epstein leased this former CHELSEA Albert Museum You Say You Want a Revolution: The V&A shop has taken up their album ‘The Who Sell Out’). The Beatles threw a party for theatre as a venue for plays as well as rock and roll shows. The 01 Royal Court, Sloane Square WRecords and Rebels 1966–1970. Throughout the late sixties, Soho, residence at 56a Carnaby Street, The Monkees here during their 1967 visit to England. Jimi Hendrix Experience opened a set here on 4th June 1967 The Royal Court Theatre regularly came into conflict with the Chelsea, Kensington and Ladbroke Grove were hubs of creativity creating a temporary retail space with a cover of ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, from Lord Chamberlain’s Office (official censor of the London stage) and revolutions in music, fashion, food, politics and sex. themed around the exhibition 07 Regent Street Polytechnic, 309 Regent Street The Beatles album, released just three days earlier. A stunned throughout the 1960s. To evade censorship, the Royal Court In Soho, a thriving centre of the popular music industry You Say You Want a Revolution? Founding members of the revolutionary rock group Pink Floyd: Paul McCartney and George Harrison looked on in the audience. -

Representations of Swinging London in 1960S British Cinema: Blowup (1966), Smashing Time (1967) and Performance (1970)

Representations of Swinging London in 1960s British Cinema: Blowup (1966), Smashing Time (1967) and Performance (1970) by Marlie Centawer Huisman A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts MA Program in Popular Culture BROCK UNIVERSITY St. Catharines, Ontario May 2011 © Marlie Centawer, 2011 Abstract This thesis explores the representation of Swinging London in three examples of 1960s British cinema: Blowup (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966), Smashing Time (Desmond Davis, 1967) and Performance (Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, 1970). It suggests that the films chronologically signify the evolution, commodification and dissolution of the Swinging London era. The thesis explores how the concept of Swinging London is both critiqued and perpetuated in each film through the use of visual tropes: the reconstruction of London as a cinematic space; the Pop photographer; the dolly; representations of music performance and fashion; the appropriation of signs and symbols associated with the visual culture of Swinging London. Using fashion, music performance, consumerism and cultural symbolism as visual narratives, each film also explores the construction of youth identity through the representation of manufactured and mediated images. Ultimately, these films reinforce Swinging London as a visual economy that circulates media images as commodities within a system of exchange. With this in view, the signs and symbols that comprise the visual culture of Swinging London are as central and significant to the cultural era as their material reality. While they attempt to destabilize prevailing representations of the era through the reproduction and exchange of such symbols, Blowup, Smashing Time, and Performance nevertheless contribute to the nostalgia for Swinging London in larger cultural memory. -

Il Giappone Di Yukio Mishima 1 -1

COMUNICATO STAMPA sabato 13 novembre inaugura la manifestazione 1 Il Giappone di Yukio Mishima Sabato 13 novembre inaugura a Cagliari, presso il Centro di Iniziative Sociali (CIS) di piazza del Carmine n.4, la manifestazione “Il Giappone di Yukio Mishima”. Il 25 novembre di quest'anno sarà il quarantesimo anniversario dalla morte di Hiraoka Kimitake (Tokyo, 14 gennaio 1925 – Tokyo, 25 novembre 1970), più noto come Yukio Mishima. All’apice della propria carriera, il grande scrittore e drammaturgo giapponese – più volte vicino al Nobel – trapassò la sua esistenza attraverso il tradizionale seppuku . Un uomo che ha saputo unire l' azione alla penna , trasformando il proprio corpo attraverso il “Sole e Acciaio” . Mishima non si è limitato alla sola attività contemplativa e letteraria, ma ha incarnato pienamente i valori della Tradizione. Ci è sembrato doveroso contribuire all'omaggio di questo straordinario autore attraverso il progetto qui presente, che, alternando cineforum a degustazioni di cibo tradizionale, invita all’approfondimento della cultura giapponese. Sarà altresì previsto un embukai di Aikido, ossia una dimostrazione di arte marziale tradizionale giapponese. La manifestazione è aperta a tutti, in particolar modo agli studenti universitari, e l’ingresso è libero. L’iniziativa è promossa dall’ Associazione Culturale Caravella con il contributo della Provincia di Cagliari, dell’Università degli Studi di Cagliari e con collaborazione del dojo Tomodachi no kai e del Sushi bar “TAMI”. Progetto: Mishima dimostrò sin da giovane il suo talento letterario con il suo primo lavoro in prosa: Hanazakari no Mori (La foresta in fiore ), completato nel 1941. Il fatto che fosse fortemente influenzato dalla scuola romantica giapponese ( Nihon Roman-ha ) farà sì che venga notato dal professore di lettere del Gakushūin, Shimizu Fumio, membro della scuola romantica. -

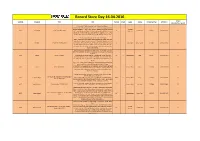

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (Ja/Nein/Über Wen?)

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (ja/nein/über wen?) Picture disc LP with artwork by Drew Millward (Foo Fighters) Broken Thrills is Beach Slang's first European release, compiling their debut EPs, both released in the US in 2014. The LP is released via Big Scary Monsters Big Scary ALIVE Beach Slang Broken Thrills (RSD 2016) LP 1 Independent 6678317 5060366783172 AT (La Dispute, Gnarwolves, Minus The Bear) and coincides with their first tour Monsters outside of the States, including Groezrock festival in Belgium and a run of UK headline dates. For fans of: Jawbreaker, Gaslight Anthem and Cheap Girls. 12'' Clear Vinyl, 4 Remixes of "Get Lost" + One Cover After the new album "Still Waters" recently released, and sustained by the lively "Back For More" and the captivating "2Good4Me", Breakbot is back ALIVE Breakbot Get Lost Remixes (RSD 2016) with a limited edition EP of 4 "Get Lost" remixes and one exclusive cover by 12" 1 Ed Banger Disco / Dance 2156290 5060421562902 AT the band Jamaica. Still with his sidekick Irfane, Breakbot is more than ever determined to make us dance with a new succession of hits each one more exciting than the last. LIMITED DOUBLE 12'' WITH PRINTED INNER SLEEVES: "ACTION" IS THE 1ST SINGLE OF CASSIUS 'S NEW ALBUM (release date 24.06.2016). This EP features 6 TRACKS, ALIVE Cassius Action (RSD 2016) Exclusively for the Record Store Day, the first single "Action" from the 12" 2 Because Music House 2156427 5060421564272 AT upcoming album releases as a double 12'' edition. -

50000 Korean Agents Military Policemen Emperor Hirohito and Rockefeller Imported from North Korea

50,000 Korean agents military policemen emperor Hirohito and Rockefeller imported from North Korea. (present amount are more over 1 million Korean spy agents to 50 million agents) A military policeman for mobilization and construction the main culprit emperor of various evils imported from North Korea, mention a name of 50,000! Kita agent Koizumi Nakasone by whom a ream was returned to kidnap victim is https://is.gd/vDD5nO taka https://is, too. gd/OeUQXw Shimonoseki 50% Korean https://is.gd/TQEKb1 Present living in Japan is the Korean army of occupation, be, it's the NO end and is the criminal release Syngman Rhee asked from Japan and survival of criminal pasturing. [The spread] "rule system in Japan". ■ The postwar is also the method to rule Japan. (The United States) back society is really similar to Japanese and is to use the naturalized citizen in Japan with a different heart as a pawn also to rule Japan after the war. I don't get away for a pawn because a motherland can't be betrayed by Japanese. A Caucasian and a black people are too conspicuous, too, so you can't come into action secretly. So Masaji arranges a naturalized citizen in Japan in an entertainment world and various fields as a Japanese VIP. Even if a country was sold, an emperor and Rockefeller imported the Korean's 50,000 construction military policemen who don't have the pain of the complete heart. Inside story of the Japanese invasion an elitist in Japan told The thing as if living in Japan takes a Japanese country over, is being uttered.