AN INTERNAL ANALYSIS of the FICTION of FLANNERY O'connor. the Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Language and Literature, Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dakini Project

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2014 The Dakini Project Kimberley Harris Idol University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Repository Citation Idol, Kimberley Harris, "The Dakini Project" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2094. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/5836113 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DAKINI PROJECT: TRACKING THE “BUTTERFLY EFFECT” IN DETECTIVE FICTION By Kimberley Harris Idol Bachelor of Arts in Literature Mount Saint Mary’s College 1989 Master of Science in Education Mount Saint Mary’s College 1994 Master of Arts in Literature California State University, Northridge 2005 Master of Fine Arts University -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This

Theologica Xaveriana ISSN: 0120-3649 ISSN: 2011-219X [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia Poggi, Alfredo Ignacio A Southern Gothic Theology: Flannery O’Connor and Her Religious Conception of the Novel∗ Theologica Xaveriana, vol. 70, 2020, pp. 1-23 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx70.sgtfoc Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=191062490018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative doi: https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx70.sgtfoc A Southern Gothic Theology: Una teología gótica sureña: Flannery O’Connor y su concepción religiosa de la Flannery O’Connor and novela Her Religious Conception Resumen: Mary Flannery O’Connor, a ∗ menudo considerada una de las mejores of the Novel escritoras norteamericanas del siglo XX, parece haber respaldado la existencia de la a “novela católica” como género particular. Alfredo Ignacio Poggi Este artículo muestra las características University of North Georgia descritas por O’Connor sobre este género, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9663-3504 puntualizando la constitución indefinida y problemática de dicha delimitación. Independientemente de la imposibilidad RECIBIDO: 30-07-19. APROBADO: 18-02-20 de definir el término, este artículo sostiene además que la explicación de O’Connor sobre el género trasciende el campo lite- rario y muestra una visión distintiva de Abstract: Mary Flannery O’Connor, often consi- la fe cristiana y una teología sofisticada dered one of the greatest North American writers of que denomino “gótico sureño”. -

Flannery O'connor

ANALYSIS “The Artificial Nigger” (1955) Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) “I suppose ‘The Artificial Nigger’ is my favorite…. And there is nothing that screams out the tragedy of the South like what my uncle calls ‘nigger statuary.’ And then there’s Peter’s denial. They all got together in that one. You are right about this negativity being in large degree personal. My disposition is a combination of Nelson’s and Hulga’s. Or perhaps I only flatter myself.” O’Connor, Letter (6 September 1955) “Well, I never had heard the phrase before, but my mother was out trying to buy a cow, and she rode up the country a-piece. She had the address of a man who was supposed to have a cow for sale, but she couldn’t find it, so she stopped in a small town and asked the countryman on the side of the road where the house was, and he said, ‘Well, you go into this town and you can’t miss it ‘cause it’s the only house in town with a artificial nigger in front of it.’ So I decided I would have to find a story to fit that.” O’Connor, Symposium, Vanderbilt U (1957) “’The Artificial Nigger’ is my favorite and probably the best thing I’ll ever write.” O’Connor, Letter (10 March 1957) “We begin here with nothing more uncommon than a rustic old man taking his rustic grandson for his first trip to the city. While their backwoodness is a bit grotesque and the old man’s vanity provides touching humor, metaphysical drama doesn’t overturn secular seeming until the man publicly denies his relationship to the boy to escape retribution and to give the humor a new dimension. -

Nixon Slates Soviet Talks BRUSSELS (AP) - Presi- Soviet - American Talks

own School Board Asks Budget Defeat SEfe STORY BELOW * Snow Ending Mixed snow and rain ending 1WDAILY FINAL - today. Partly cloudy and cold ) Red Bank, Freehold 7" tonight and tomorrow. 1 Long Branch EDITION MM Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 169 RED BANK, N. J., MONDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 1969 18 PAGES 10 CENTS SAIGON (AP) - Viet Cong and North Vietnamese provincial capitals, and 29 district capitals. Some towns tian frontier Sunday in an operation to cut enemy supply Saigon was shelled twice yesterday, for the first time troops raked more than 50 towns and military posts with were hit several times. lines. There were no casualties, but the two losses raised since the halt in the bombing of. North Vietnam last Nov. 1. rockets, mortars and. light ground attacks today in the sec- Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, taking a plane to return to 2,362 the number of American helicopters lost in the war. Fifteen civilians were killed and 48 were wounded. But ond day of countrywide attacks. American officers said to the Paris peace talks, said he would recommend a re- AROUND U.S. BASES the capital was spared any shelling today. the enemy had started a spring offensive intended to gen- sumption of the bombing of North Vietnam if shelling of The bulk of the fighting occurred north and northwest of 'A BRAZEN THING' erate pressure from the American public for concessions at South Vietnam's cities continued. He said his South Viet- Saigon, around the big American bases at Long Blnh, Bien An American official said the rocket attacks on the . -

Sacred Music and Religious Themes

Guide to the Sam DeVincent Collection of Illustrated American Sheet Music, Series 10: Sacred Music and Religious Themes NMAH.AC.0300.S10 NMAH Staff Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Subseries 10.1: Adam, Eve, and Eden, 1882-1971................................................. 5 Subseries 10.2: Angels, 1849-1961......................................................................... 5 Subseries 10.3: Bells and Chimes, 1848-1956........................................................ 5 Subseries 10.4: Biblical Characters and Stories, 1876-1986................................... 6 Subseries 10.5: Cathedral, Chapel, Church, 1866-1966.......................................... 6 Subseries 10.6: Choir, 1880-1937........................................................................... -

Flannery O'connor's Images of the Self

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 1978 CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF MICHAEL JOHN LEE Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEE, MICHAEL JOHN, "CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF" (1978). Doctoral Dissertations. 1210. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1210 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document ' ave been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

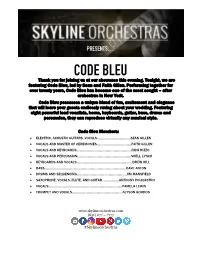

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Hydrologic Soil Groups

AppendixExhibitAppendix A: Hydrologic AB Soil Synthetic Groups Hydrologic for theRainfall United SoilStates Distributions Groups and Rainfall Data Sources Soils are classified into hydrologic soil groups (HSG’s) Disturbed soil profiles to indicate the minimum rate of infiltration obtained for bareThe highest soil after peak prolonged discharges wetting. from Thesmall HSG watersheds’s, which arein the UnitedAs a result States of areurbanization, usually caused the soil by profileintense, may brief be rain- con- A,falls B, that C, and may D, occur are one as distinctelement eventsused in or determining as part of a longersiderably storm. These altered intense and the rainstorms listed group do not classification usually ex- may runofftended curve over anumbers large area (see and chapter intensities 2). For vary the greatly. conve- One commonno longer practice apply. inIn rainfall-runoffthese circumstances, analysis use is tothe develop follow- niencea synthetic of TR-55 rainfall users, distribution exhibit A-1 to uselists in the lieu HSG of actualclassifi- storming events. to determine This distribution HSG according includes to themaximum texture rainfall of the cationintensities of United for the States selected soils. design frequency arranged in a sequencenew surface that soil, is critical provided for thatproducing significant peak compaction runoff. has not occurred (Brakensiek and Rawls 1983). TheSynthetic infiltration raterainfall is the rate distributions at which water enters the soil at the soil surface. It is controlled by surface condi- HSG Soil textures tions.The length HSG ofalso the indicates most intense the transmission rainfall period rate contributing—the rate to the peak runoff rate is related to the time of concen- A Sand, loamy sand, or sandy loam attration which (T thec) for water the watershed.moves within In thea hydrograph soil. -

When December Burns Cold Like a Stone Rise to the Unknown I Now

When December Burns Cold like a stone rise to the unknown I now drown in despair when December burns Locked in one’s mind my state of being, denial Drag me away with your toxin this bliss lasts just for one moment What’s left of this world? Where’s your true purpose? These flames seem to wait atop a hill Breath to the wind I’m built up with sin What can you find beneath my ashes? See hope in others’ eyes this earth leaves nothing to thrive living beside the dead upon stacks of burial mounds My skin starts to boil The stench is too grim to bear But now there's no turning back I will not perish in dissent Cold like a stone Rise to the unknown I now drown in despair When December burns Where's your god? Where's your faith when we all die the same? The smoke now rises, the sky turns pale This is my end, my farewell Your life leaves nothing for me Burn me again and again I stand alone on this hill Flames succumb all around Black like coal In the unknown I now burn In December Jeremy Farfan - Guitar, Vocals Efrain Farfan - Guitar, Vocals Manolo Estrada - Drums Martin Tune - Bass Recorded at Atomic Sound, Red Hook Brooklyn April 20 and May 28, 2019 Recorded by Dakota Bowman Mixed by Neil Kernon Mastered by Alan Douches at West West Side Music Starved For Energy I'm Crawling through earth and through stone I gasp for one last breath of your innocent silence Covered in dirt I know you bare this hurt alone Contemplating suicide A look inside this tangled mind A noose that hangs six feet high Can you see it sway? The clouds now merge With obscure shades of grey The fields then burn With the smell of decay What more can be said For a wind thats passed This unspoken whisper Lingers in smoke as dead eyes stare down! I drown my tears over flames That vanish snow And I can't fight the dark that's consumed me My sanity has left me here. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

FLANNERY a Life of Flannery O'connor Brad Gooch

FLANNERY A Life of Flannery O’Connor Brad Gooch For Paul Raushenbush CONTENTS Prologue Walking Backwards PART ONE Chapter One Savannah Chapter Two Milledgeville: “A Bird Sanctuary” Chapter Three “M.F.O.C.” Chapter Four Iowa Chapter Five Up North PART TWO Chapter Six The Life You Save Chapter Seven The “Bible” Salesman Chapter Eight Freaks and Folks Chapter Nine Everything That Rises Chapter Ten Revelation Acknowledgments Notes As for biographies, there won’t be any biographies of me for only one reason, lives spent between the house and the chicken yard do not make exciting copy. --Flannery O’Connor PROLOGUE: WALKING BACKWARDS When Flannery O’Connor was five years old, the Pathe newsreel company dispatched a cameraman from their main offices in New York City to the backyard of the O’Connor family home in Savannah, Georgia. The event, as O’Connor wryly confessed in an essay in Holiday magazine in September 1961, almost exactly three decades later, “marked me for life.” Yet the purpose of the visit from “the New Yorker,” as she labeled him, wasn’t entirely to film her, outfitted in her best double-breasted dark coat and light- wool knit beret, but rather to record her buff Cochin Bantam, the chicken she reputedly taught to walk backwards. How a Yankee photographer wound up for a memorable half-day at the bottom of the O’Connors’ steep back stairs isn’t entirely clear. One rumor credits the connections of Katie Semmes, a well-to-do dowager cousin who lived in the grander house next door, and whose tall windows looked down on the yard where the filming took place. -

FINESSE 0.98, Frequency Domain Interferometer Simulation Software

FINESSE 0.98 Frequency domain INterferomEter Simulation SoftwarE Andreas Freise Finesse is a fast interferometer simulation software. For a given optical setup, the pro- gram computes the light field amplitudes at every point in the interferometer assuming a steady state. To do so, the interferometer description is translated into a set of linear equa- tions that are solved numerically. For convenience, a number of standard analyses can be performed automatically by the program, namely computing modulation-demodulation error signals, transfer functions and shot-noise limited sensitivities. Finesse can per- form the analysis using a plane-wave approximation or Hermite-Gauss modes. The latter allows to compute the effects of mode matching and misalignments. In addition, error signals for automatic alignment systems can be modeled. 28.02.2005 Finesse and the accompanying documentation and the example files have been written by: Andreas Freise European Gravitational Observatory Via E. Amaldi 56021 Cascina (PI) Italy [email protected] Parts of the Finesse source and ’mkat’ have been written by Gerhard Heinzel, the document ’sidebands.ps’ by Keita Kawabe, the Octave examples and its description by Gabriele Vajente. The software and documentation is provided as is without any warranty of any kind. Copyright c by Andreas Freise 1999-2005. For the moment I only distribute a binary version of the program. You may freely copy and distribute the program for non-commercial purposes only. Especially you should not charge fees or request donations for any part of the Finesse distribution (or in connection with it) without the author’s written permission. No other rights, such as ownership rights, are transferred.