Looking Through Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soh6.6.11Newreleaseb

RETURNS WITH A THREE LP COLLECTION! MMMIIIRRRRRROOORRR BBBAAALLLLLL::: LLLIIIVVVEEE &&& MMMOOORRREEE This is the ULTIMATE live set! All of Def Leppard’s hits, recorded live for the first time ever, are on this 180 gram virgin vinyl, 3 LP collection. FOUR NEW SONGS ARE FEATURED, INCLUDING “UNDEFEATED,” THE CURRENT #1 SINGLE AT CLASSIC ROCK RADIO. TITLE: MIRROR BALL ‐ LIVE & MORE RELEASE DATE: 7/5/11 LABEL: MAILBOAT RECORDS UPC: 698268952003 CATALOG #: MBR 9520 CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO THE #1 SONG “UNDEFEATED” LP 1 LP 3 Rock! Rock (‘Til You Drop) Rock of Ages SUMMER TOUR DATES WITH SPECIAL GUEST HEART Rocket Let’s Get Rocked Animal June 15 West Palm Beach, FL July 23 New Orleans, LA Bonus Live: June 17 Tampa, FL July 24 San Antonio, TX C’mon C’mon Action June 18 Atlanta, GA August 8 Sturgis, SD Make Love Like A Man Bad Actress June 19 Orange Beach, AL August 10 St. Louis, MO Too Late For Love Undefeated June 22 Charlotte, NC August 13 Des Moines, IA Foolin’ June 24 Raleigh, NC August 16 Toronto, CAN Kings of the World June 25 Virginia Beach, VA August 17 Detroit, MI Nine Lives New Songs: June 26 Philadelphia, PA August 19 Louisville, KY Love Bites Undefeated June 29 Scranton, PA August 20 Pittsburgh, PA Kings of the World June 30 Boston, MA August 21 Buffalo, NY July 2 Uncasville, CT August 24 Cleveland, OH LP 2 It’s All About Believin’ July 3 Hershey, PA August 26 St. Paul, MN Rock On July 5 Milwaukee, WI August 27 Kansas City, MO Two Steps Behind July 7 Cincinnati, OH August 29 Denver, CO Bringin’ on the Heartbreak July 9 Washington, DC -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Title: Title: Title

Title: 'Dentity Crisis in - Christopher Durang Explains it all for You / COL Author: Durang, Christopher Publisher: Avon Books 1983 Description: roy comedy - dark - mental illness five characters two male; three female one act suggested for high school. "Black comedy attacking pretensions of psychiatry. Patient recovering from nervous breakdown finds her identity interchangeable with those of the doctor and her family." Title: 'Dentity Crisis in - Christopher Durang - 27 Short Plays / COL Author: Durang, Christopher Publisher: Smith and Kraus 1995 Description: roy comedy - dark - mental illness five characters two male; three female one act suggested for high school. "Black comedy attacking pretensions of psychiatry. Patient recovering from nervous breakdown finds her identity interchangeable with those of the doctor and her family." Title: 'Dentity Crisis in - Three Short Plays / COL Author: Durang, Christopher Publisher: Dramatists Play Service 1979 Description: roy comedy five characters two male; three female one act "Recovering from a nervous breakdown, Jane is nursed and nagged by her relentlessly cheerful mother, and confused by her oversexed brother - who keeps changing into her father, her grandfather and her mother's french lover. Eventually all (including Jane's psychiatrist, who undergoes a sex change operation and swaps places with his wife) change characters again and become Jane herself - leaving her with no identity at all and pointing up the near impossibility of self-identification in our uncertain times." Title: 1-900-Desperate in - Christopher Durang - 27 Short Plays / COL Author: Durang, Christopher Publisher: Smith and Kraus 1995 Description: roy comedy five characters one male; three female; one child one act Gretchen, nagged by her mother about her empty love life, calls a romance talk line and finds only other women and one young man named Scuzzy. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Full Cast Announced for the Treatment

PRESS RELEASE Friday 24 February 2017 THE ALMEIDA THEATRE ANNOUNCES THE FULL CAST FOR THE TREATMENT, MARTIN CRIMP’S CONTEMPORARY SATIRE, DIRECTED BY LYNDSEY TURNER CHOREOGRAPHER ARTHUR PITA JOINS THE CREATIVE TEAM Joining Aisling Loftus and Matthew Needham in THE TREATMENT will be Gary Beadle, Ian Gelder, Ben Onwukwe, Julian Ovenden, Ellora Torchia, Indira Varma, and Hara Yannas. The Treatment begins previews at the Almeida Theatre on Monday 24 April and runs until Saturday 10 June. The press night is Friday 28 April. New York. A film studio. A young woman has an urgent story to tell. But here, people are products, movies are money and sex sells. And the rights to your life can be a dangerous commodity to exploit. Martin Crimp’s contemporary satire is directed by Lyndsey Turner, who returns to the Almeida following her award-winning production of Chimerica. The Treatment will be designed by Giles Cadle, with lighting by Neil Austin, composition by Rupert Cross, fight direction by Bret Yount, sound by Chris Shutt, and voice coaching by Charmian Hoare. The choreographer is Arthur Pita. Casting is by Julia Horan. ALMEIDA QUESTIONS In response to The Treatment - where it’s material that matters – Whose Life Is It Anyway? continues the Almeida’s programme of pre-show discussions as a panel delves into the worldwide fascination with constructed realities in art and in life. When you sell your story is your life still your own? In the golden age of social media - where immaculately contrived worlds are labelled as real life - what is the cost? Can truth be traced in art at all? The panel includes Instagram star Deliciously Stella, Made In Chelsea producer Nick Arnold, and Anita Biressi, Professor of Media and Communications at Roehampton University. -

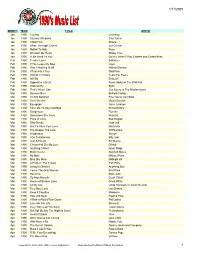

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

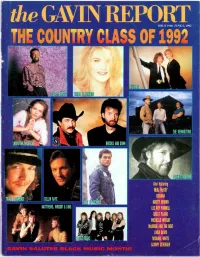

The GAVIN REPORT the COUNTRY CLASS of 1992

the GAVIN REPORT THE COUNTRY CLASS OF 1992 _; Also featuring NEAL McCOY DIXIANA COLLIN RAYE MARTY BROWN LEE ROY PARNELL GREAT PLAINS MICHELLE WRIGHT McBRIDE AND THE RIDE LINDA DAVIS MICHAEL WHITE SAMMY KERSHAW GAVIN e A K.lLITES BLACK MUSIC MdfleekrTlW In the dictionary, next to the wo -d "summer,' is a picture of the Love Shack. The video for "Roam" changed the way you eat bagels and bananas forever. Cosmic Thing comes to nearly four million pieces of history. T{ -at about cover; the last lime tl-e B -52's made a reco-d.Thisigk, the first ry direction. s Produced by Don Was Direct Manage -rent Group -Stemmei Jensen & Martin Krkup 9 ®' 992 Reprise Recoris. ft s a sock hop it +our own private Idc óo the GAVIN REPORT GAVIN AT A * Indicates Tie it» 4rv URBAN MOST ADDED MOST ADDED THE CURE EN VOGUE YO YO Friday I'm In Love (Fiction/Elektra) Giving Him Something He Can Feel (Atco/EastWest Home Girl Don't Play Dat (Atco/EastWest America) DEF LEPPARD America) ERIC B & RAKIM Make Love Like A Man (Mercury) TLC Don't Sweat The Technique (MCA) TOAD THE WET SPROCKET Baby -Baby -Baby (LaFace/Arista) X -CLAN Xodus (Polydor/PLG) All I Want (Columbia) ALYSON WILLIAMS Just My Luck (RAL/OBR/Columbia) HEAVY D. & THE BOYZ RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RETAIL MERYN CADELL DAVID BLACK You Can't See What I Can See The Swea er (Sire/Reprise) Nobody But You (Bust It/Capitol) (MCA) itAe RADIO SHANTE RICHARD MARX MARIAN CAREY Big Mama (Livin' Large/ Take This Heart (Capitol) I'll Be There (Columbia) Tommy Boy) COUNTRY MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED RICHARD -

Egents Get Raise, Enrollment Gets

1"4«k msu Career Fair 92' JDYStery solved page2 easts for pear arlng lovers page 10 musical sport page 13 t night page 13 . TN R H.. -OPO NENT Strand Union Ballrooms were full of activity Thursday as MSU students met with potential employers. Over 100 corporations sent recruiters to talk to students who were interested in post-graduation employment. egents get raise, enrollment gets cut gents vote for pay raise Downsizing is here have supported raises al this time." Regent KenniL Schwancke of Missoula defended the raises, saying thal Montana's universities tagged behind by Chris Junghans red Freedman cenain peer institutions, such as the University of Norlh Exponent staff writer ~nt news writer Dakota, in their pay of dean-level and above employees. He also noted that those employees have the highest turnover rate within the Montana University System (MUS). Raising admission standards would be the fairest way of administer oard ofRegents recently gave itself and high-level He emphasized that deans are pan of that system, as well. ing a Board of Regents' plan to cul 10.49 percent of Montana State's y employees a 3 1(2 percent raise. The Regents This was not the first Lime that Farmer had differences enrollment over the next four years. elena on July 30-31 and gave themselves and all with the Board of Regents. That's what MSU President Mike Malone told the Exponent about s Dean-level and above a pay increase. The raise ''The Board of Regents has no checks and balances the tentative plan 10 cut enrollment at Montana colleges by nearly 4,000 verage increase of 3 1(2 percent, with 1(2 percent whatsoever. -

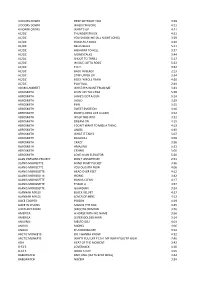

112 Dance with Me 112 Peaches & Cream 213 Groupie Luv 311

112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 213 GROUPIE LUV 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 BEAUTIFUL DISASTER 311 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 CHAMPAGNE 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 DON'T STAY HOME 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 311 PURPOSE ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB 10 M POP MUZIK 10 YEARS WASTELAND 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 FT. SEAN PAUL NA NA NA NA 112 FT. SHYNE IT'S OVER NOW (RADIO EDIT) 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP 1TYM WITHOUT YOU 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT 2 LIVE CREW DAISY DUKES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW DIRTY NURSERY RHYMES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW FACE DOWN *** UP (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME ***** (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 PAC 16 ON DEATH ROW 2 PAC 2 OF AMERIKAZ MOST WANTED 2 PAC ALL EYEZ ON ME 2 PAC AND, STILL I LOVE YOU 2 PAC AS THE WORLD TURNS 2 PAC BRENDA'S GOT A BABY 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (EXTENDED MIX) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (NINETY EIGHT) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) 2 PAC CAN'T C ME 2 PAC CHANGED MAN 2 PAC CONFESSIONS 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC DEATH AROUND THE CORNER 2 PAC DESICATION 2 PAC DO FOR LOVE 2 PAC DON'T GET IT TWISTED 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2 PAC GHOST 2 PAC GOOD LIFE 2 PAC GOT MY MIND MADE UP 2 PAC HATE THE GAME 2 PAC HEARTZ OF MEN 2 PAC HIT EM UP FT. -

2018 01 12 RR 12 2017 All Played List1.Xlsx

3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3:49 3 DOORS DOWN WHEN I'M GONE 4:11 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 4:21 AC/DC THUNDERSTRUCK 4:51 AC/DC YOU SHOOK ME (ALL NIGHT LONG) 3:29 AC/DC HARD AS A ROCK 4:30 AC/DC HELLS BELLS 5:11 AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL 3:27 AC/DC MONEYTALKS 3:44 AC/DC SHOOT TO THRILL 5:17 AC/DC WHOLE LOTTA ROSIE 5:22 AC/DC T.N.T. 3:32 AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 2:13 AC/DC STIFF UPPER LIP 3:34 AC/DC ROCK 'N ROLL TRAIN 4:20 AC/DC PLAY BALL 2:44 ADAM LAMBERT WHATAYA WANT FROM ME 3:43 AEROSMITH LIVIN' ON THE EDGE 5:38 AEROSMITH JANIE'S GOT A GUN 5:14 AEROSMITH JADED 3:29 AEROSMITH PINK 3:55 AEROSMITH SWEET EMOTION 4:16 AEROSMITH DUDE (LOOKS LIKE A LADY) 4:12 AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY 3:32 AEROSMITH DREAM ON 4:15 AEROSMITH I DON'T WANT TO MISS A THING 4:13 AEROSMITH ANGEL 4:49 AEROSMITH WHAT IT TAKES 5:07 AEROSMITH RAG DOLL 4:09 AEROSMITH CRAZY 3:56 AEROSMITH AMAZING 5:31 AEROSMITH CRYING 5:00 AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR 5:20 ALAN PARSONS PROJECT DON'T ANSWER ME 2:51 ALANIS MORISETTE HAND IN MY POCKET 3:36 ALANIS MORISETTE YOU OUGHTA NOW 4:06 ALANIS MORISSETTE HEAD OVER FEET 4:12 ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC 3:42 ALANIS MORISSETTE HANDS CLEAN 4:17 ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK U 3:57 ALANIS MORISSETTE GUARDIAN 3:24 ALANNAH MYLES BLACK VELVET 4:37 ALANNAH MYLES LOVER OF MINE 4:12 ALICE COOPER POISON 4:19 ALICE IN CHAINS MAN IN THE BOX 4:45 ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL 3:26 AMERICA A HORSE WITH NO NAME 3:56 AMERICA SISTER GOLDEN HAIR 3:14 ANAVRIN MESTO IDEJ 4:03 ANOUK MICHEL 4:06 ANOUK R U KIDDING ME 3:14 ARCTIC MONKEYS DO I WANNA KNOW 4:32 ARCTIC MONKEYS WHY'D -

Guide to Plays for Performance

Guide to Plays for Performance Welcome to our Guide to Plays for Performance! I hope this Guide will not only be a useful tool for you in helping to choose next season’s play, but also a valuable companion throughout your career in the theatre. The Guide will give you a good overview of our list with detailed information on our most- performed plays as well as new releases and acquisitions. A more comprehensive version of the Guide is available online, and you are welcome to print off any sheets that are of particular interest to you there. Towards the end of this guide you will find a detailed listing of all our plays for performance, including cast details. If you find a play there that you would like a closer look at, just let me know and I will be happy to send you an approval copy of the script. If you wish to receive our quarterly supplements, with information about the most recent acquisitions, you must let me have an email address (send to: [email protected]) so that I can add you to our electronic mailing list. Check before rehearsals May I remind you that it is essential that before rehearsals begin, you check availability with me, as inclusion in the Guide does not necessarily indicate that amateur rights have been released, and some plays may be withdrawn later on without notice. I hope you will find an exciting and inspiring play for a future production in this Guide and look forward to hearing from you. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No.