A Winterreise Discography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

Edith Mathis Mozart | Bartók | Brahms | Schumann | Strauss Selected Lieder Karl Engel Wolfgang Amadé Mozart (1756–1791) Robert Schumann (1810–1897) Das Veilchen K

HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Edith Mathis Mozart | Bartók | Brahms | Schumann | Strauss Selected Lieder Karl Engel Wolfgang Amadé Mozart (1756–1791) Robert Schumann (1810–1897) Das Veilchen K. 476 2:47 Nine Lieder from Myrthen, Op. 25 Als Luise die Briefe ihres ungetreuen Liebhabers verbrannte K. 520 1:41 Widmung 2:11 Abendempfindung an Laura K. 523 4:45 Der Nussbaum 3:27 Dans un bois solitaire K. 308 (295b) 2:54 Jemand 1:36 Der Zauberer K. 472 2:48 Lied der Braut I («Mutter, Mutter, glaube nicht») 2:01 Lied der Braut II («Lass mich ihm am Busen hängen») 1:34 Béla Bartók (1881–1945) Lied der Suleika («Wie mit innigstem Behagen») 2:48 Village Scenes. Slovak Folksongs, Sz. 78 Im Westen 1:16 Was will die einsame Thräne 2:59 Heuernte 1:33 Hauptmanns Weib 1:55 Bei der Braut 1:57 Hochzeit 3:30 Wiegenlied 5:03 Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Burschentanz 2:47 Schlechtes Wetter, Op. 69 No. 5 2:29 Die Nacht, Op. 10 No. 3 2:55 Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) Ach, Lieb, ich muss nun scheiden, Op. 21 No. 3 2:08 Five Songs from 42 Deutsche Volkslieder, WoO 33 Meinem Kinde, Op. 37 No. 3 2:19 Hat gesagt – bleibt’s nicht dabei, Op. 36 No. 3 2:31 Erlaube mir, feins Mädchen 1:15 In stiller Nacht 3:12 encore announcement: Edith Mathis 0:10 Wie komm’ ich denn zur Tür herein? 2:19 Da unten im Tale 2:29 Hugo Wolf (1860–1903) Feinsliebchen, du sollst 4:14 Auch kleine Dinge können uns entzücken from the Italienisches Liederbuch 2:42 recorded live at LUCERNE FESTIVAL (Internationale Musikfestwochen Luzern) Edith Mathis soprano Previously unreleased Karl Engel piano The voice of music The soprano Edith Mathis According to an artist feature of the soprano Edith Mathis, published by the music maga- zine Fono Forum in 1968, an engagement at the New York Met was a “Pour le Mérite” for a singer. -

Romantic Listening Key

Name ______________________________ Romantic Listening Key Number: 7.1 CD 5/47 pg. 297 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 4th mvmt Composer: Berlioz Genre: Program Symphony Characteristics Texture: ____________________________________________________ Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: timp start, high bsn solo Number: 7.2 CD 6/11 pg 339 Title: The Moldau Composer: Smetana Genre: symphonic poem Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: flute start Sections: two springs, the river, forest hunt, peasant wedding, moonlight dance of river nymphs, the river, the rapids, the river at its widest point, Vysehrad the ancient castle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.3 CD 5/51 pg 229 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 5th mvmt (Dream of a Witch's Sabbath) Composer: Berlioz Genre: program symphony Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: funeral chimes, clarinet idee fix, trills & grace notes Number: 7.4 website Title: 1812 Overture Composer: Tchaikovsky Genre: concert overture Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: soft beginning, hunter motive, “Go Napoleon”, the battle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.5 website Title: The Sorcerer's Apprentice -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

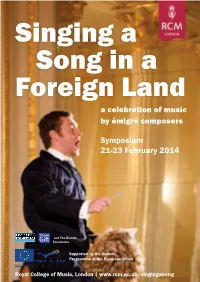

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

The Blue Review Literature Drama Art Music

Volume I Number III JULY 1913 One Shilling Net THE BLUE REVIEW LITERATURE DRAMA ART MUSIC CONTENTS Poetry Rupert Brooke, W.H.Davies, Iolo Aneurin Williams Sister Barbara Gilbert Cannan Daibutsu Yone Noguchi Mr. Bennett, Stendhal and the ModeRN Novel John Middleton Murry Ariadne in Naxos Edward J. Dent Epilogue III : Bains Turcs Katherine Mansfield CHRONICLES OF THE MONTH The Theatre (Masefield and Marie Lloyd), Gilbert Cannan ; The Novels (Security and Adventure), Hugh Walpole : General Literature (Irish Plays and Playwrights), Frank Swinnerton; German Books (Thomas Mann), D. H. Lawrence; Italian Books, Sydney Waterlow; Music (Elgar, Beethoven, Debussy), W, Denis Browne; The Galleries (Gino Severini), O. Raymond Drey. MARTIN SECKER PUBLISHER NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET ADELPHI The Imprint June 17th, 1913 REPRODUCTIONS IN PHOTOGRAVURE PIONEERS OF PHOTOGRAVURE : By DONALD CAMERON-SWAN, F.R.P.S. PLEA FOR REFORM OF PRINTING: By TYPOCLASTES OLD BOOKS & THEIR PRINTERS: By I. ARTHUR HILL EDWARD ARBER, F.S.A. : By T. EDWARDS JONES THE PLAIN DEALER: VI. By EVERARD MEYNELL DECORATION & ITS USES: VI. By EDWARD JOHNSTON THE BOOK PRETENTIOUS AND OTHER REVIEWS: By J. H. MASON THE HODGMAN PRESS: By DANIEL T. POWELL PRINTING & PATENTS : By GEO. H. RAYNER, R.P.A. PRINTERS' DEVICES: By the Rev.T. F. DIBDIN. PART VI. REVIEWS, NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE. Price One Shilling net Offices: 11 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.G. JULY CONTENTS Page Post Georgian By X. Marcel Boulestin Frontispiece Love By Rupert Brooke 149 The Busy Heart By Rupert Brooke 150 Love's Youth By W. H. Davies 151 When We are Old, are Old By Iolo Aneurin Williams 152 Sister Barbara By Gilbert Cannan 153 Daibutsu By Yone Noguchi 160 Mr. -

Schumann Spanisches Liederspiel Brahms Liebeslieder-Walzer Mathis · Fassbaender Schreier · Berry Werba · Schilhawsky

ORFEO D’OR Schumann Spanisches Liederspiel Brahms Liebeslieder-Walzer Mathis · Fassbaender Schreier · Berry Werba · Schilhawsky Live Recording 25. August 1974 Bewahrung des Unwiederholbaren Preserving the Unrepeatable 1920 wurden die Salzburger Festspiele ge- The Salzburg Festival was founded in 1920. gründet. Seither treffen einander alljähr- Ever since then artists and music lovers from lich an einem der Schnittpunkte europäi- around the world have been meeting an- scher Kultur Künstler und Publikum aus aller nual ly at this crossroads of European cul- Welt. Viel geliebt und oft gescholten waren ture. Much loved and often chided, the die Salzburger Festspiele in den letzten hun- Salzburg Festival was exposed to many and dert Jahren den unterschiedlichsten Verän- varied changes during the last 100 years. Yet derungen ausgesetzt – und doch: Was die the original idea as envisioned by its foun- Väter des Festspielgedankens als Vision ent- ders – a place where art could flourish under wickelt hatten – einen Ort, an dem Kunst extraordinarily favourable conditions, whe- unter außer ordentlichen Bedingungen ‚Ereig- re it could become a truly great event – has nis’ wird –, das hat sich auf wunderbare Wei- been confirmed time and again in wonder- se immer wieder neu bestätigt. ful ways. In beinahe jedem Festspielsommer hat es in Almost every summer there have been Salzburg Aufführungen gegeben, die von performances in Salzburg that the partici- den Mitwirkenden, aber auch vom Publikum pants as well as the public have felt to be als ‚unwiederholbar’ empfunden wurden. unrepeatable. Apart from people’s memo- Solche Eindrücke zu bewahren, vermag – ries, these impressions can be preserved außer der lebendigen Erinnerung – einzig only by means of acoustic documentation. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2018 This

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2018 This is the fifteenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2017-November 2018). The 130 selections have come from 25 members of the team and 70 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources - I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, 8 have received two nominations: Mahler and Strauss with Sergiu Celibidache on the Munich Phil choral music by Pavel Chesnokov on Reference Recordings Shostakovich symphonies with Andris Nelsons on DG The Gluepot Connection from the Londinium Choir on Somm The John Adams Edition on the Berlin Phil’s own label Historic recordings of Carlo Zecchi on APR Pärt symphonies on ECM works for two pianos by Stravinsky on Hyperion Chandos was this year’s leading label with 11 nominations, significantly more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2400 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year, but this year the choice was a little easier than usual. Pavel CHESNOKOV Teach Me Thy Statutes - PaTRAM Institute Male Choir/Vladimir Gorbik rec. 2016 REFERENCE RECORDINGS FR-727 SACD The most significant anniversary of 2018 was that of the centenary of the death of Claude Debussy, and while there were fine recordings of his music, none stood as deserving of this accolade as much as the choral works of Pavel Chesnokov. -

40 JAHRE FRANZ-SCHUBERT-INSTITUT Internationaler Meisterkurs Für Liedinterpretation 2018Konzerte | Teilnehmer | Dozenten EHRENSCHUTZ KONZERTE 2018 Dipl

2010 40 JAHRE FRANZ-SCHUBERT-INSTITUT Internationaler Meisterkurs für Liedinterpretation 2018Konzerte | Teilnehmer | Dozenten EHRENSCHUTZ KONZERTE 2018 Dipl. Ing. Stefan Szirusek Termine 40 Jahre Schubertiaden in Baden LiederabendSa. 28. Juli, 17.00 Uhr Erstmals ohne den Badener Kulturpreisträger, Prof. Dr. Im Rahmen des Meisterkurses für Liedinterpretation Deen Larsen, der uns völlig Stift Heiligenkreuz, Kaisersaal überraschend im Jänner 2018 verlassen hat. Damit Eintritt frei, Spenden erbeten ist die Seele, der Motor und der Initiator dieser weltweit beachteten Ausbildungs- und Konzert- serie von uns gegangen. Seine Witwe, Verena Larsen, hat die Verantwortlichen der „Schubert- tage Baden“ um sich geschart um diese Kultur- schiene auf die Art und Weise, wie es Prof. Dr. FestkonzertMo. 30. Juli, 20.00 Uhr Deen Larsen angedacht hatte, weiterzuführen. 40 Jahre Franz-Schubert-Institut Ich wünsche dem neuen Team unter der Leitung von Vreni Larsen viel Erfolg und gutes Gelingen! in memoriam Dr. Deen Larsen Es musizieren Meisterlehrer und ehemalige Studenten Stadtpfarrkirche St. Stephan, Baden bei Wien Dipl. Ing. Stefan Szirucsek Eintritt frei, Spenden erbeten Bürgermeister www.schubert-institut.at 2 I Meisterkurs 2018 40 JAHRE SCHUBERT-INSTITUT Meisterkurs 2018 Im Herbst 1977 kam Deen Larsen von einem wenig erfolgreichen Sommerkurs für Liedinterpretation zurück, und beschloss "let's do it better, let's create our own master course". So fand im Sommer 1978 LiederabendSa. 28. Juli, 17.00 Uhr der erste Meisterkurs des Franz-Schubert-Institutes statt. Im Rahmen des Meisterkurses für Liedinterpretation Die Kernidee des Kurses, dem Wort und nender Energie suchte er auf vielen Rei- Stift Heiligenkreuz, Kaisersaal dem Gedicht das Hauptaugenmerk zu sen und Meisterkursen an den besten Eintritt frei, Spenden erbeten widmen, stieß bei den Größen der Lied- Musikuniversitäten auf der ganzen Welt kunst von Anfang an auf reges Interesse. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Alban Berg War, Namentlich Seines Wozzeck, Und Dass Dieser Aus Nationalistischen Gründen in Tschechien Bekämpft Wurde

NEUIGKEITENMUSIK UND InFORMATIONEN VON DER UnBLATTERIVERSAL EDITION 3 FRIEDRICH »Frei muss man einfach sein …« CERHA ALBAN »Wozzeck« und »Lulu« – Fassungsfragen BERG LEOš Nachruf von Max Brod Janáček PIERRE und Patrice Chéreau über »Aus einem Totenhaus« BOULEZ G EORGES »Klarheit wie Sternenblitze« LENTZ DAVID »Drama und Musik« SAWER LUKE »Brennglas und Lupe« BEDFORD Kim Kowalke über KURT WEILL Salzburg contemporary Christoph Eschenbach · Pablo Heras-Casado Heinz Holliger · Johannes Kalitzke · Zubin Mehta Simon Rattle · Franz Welser-Möst Thomas Demenga · Elīna Garanča · Matthias Goerne Thomas Hampson · Håkan Hardenberger · Carl Hieger Ursula Holliger · Ruth Killius · Anita Leuzinger Alexander Lonquich · Ulrich Matthes · Horst Maria Merz Felix Renggli · Peter Stein · Thomas Zehetmair Berliner Philharmoniker · The Cleveland Orchestra · The Collegiate Chorale Ensemble Contrechamps · Israel Philharmonic Orchestra · Klangforum Wien Latvian Radio Choir · Mozarteumorchester Salzburg NDR Sinfonieorchester · oesterreichisches ensemble für neue musik ORF Radio-Symphonieorchester Wien Wiener Philharmoniker · Zehetmair Quartett supported by URAUFFÜHRUNGEN Auftragswerke von: Georg Friedrich Haas ·Heinz Holliger Gustav Friedrichsohn · Johannes Maria Staud SALZBURGER FESTSPIELE 20. JULI – 2. SEPTEMBER 2012 TICKETS &INFORMATIONEN ZUM FESTSPIELPROGRAMM Tel. +43-662-8045-500 · www.salzburgfestival.at Global sponsors of the SALZBURG FESTIVAL salzburg contemporary_210x280.indd 2 23.04.12 07:50 Mai 2012 Musikblätter 3 Liebe Musikfreunde, Sie halten bereits -

Festival 2021

FESTIVAL 2021 leedslieder1 @LeedsLieder @leedsliederfestival #LLF21 LEEDS LIEDER has ‘ fully realised its potential and become an event of INTERNATIONAL STATURE. It attracts a large, loyal and knowledgeable audience, and not just from the locality’ Opera Now Ten Festivals and a Pandemic! In 2004 a group Our Young Artists will perform across the weekend of passionate, visionary song enthusiasts began and work with Dame Felicity Lott, James Gilchrist, programming recitals in Leeds and this venture has Anna Tilbrook, Sir Thomas Allen and Iain steadily grown to become the jam-packed season Burnside. Iain has also programmed a fascinating we now enjoy. With multiple artistic partners and music theatre piece for the opening lunchtime thousands of individuals attending our events recital. New talent is on evidence at every turn in every year, Leeds Lieder is a true cultural success this Festival. Ema Nikolovska and William Thomas story. 2020 was certainly a year of reacting nimbly return, and young instrumentalists join Mark and working in new paradigms. We turned Leeds Padmore for an evening presenting the complete Lieder into its own broadcaster and went digital. Canticles by Britten. I’m also thrilled to welcome It has been extremely rewarding to connect with Alice Coote in her Leeds Lieder début. A recital not audiences all over the world throughout the past 12 to miss. The peerless Graham Johnson appears with months, and to support artists both internationally one of his Songmakers’ Almanac programmes and known and just starting out. The support of our we welcome back Leeds Lieder favourites Roderick Friends and the generosity shown by our audiences Williams, Carolyn Sampson and James Gilchrist.