Psychology and Economics Jean Tirole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Power and Regulation

THE PRIZE IN ECONOMIC SCIENCES 2014 POPULAR SCIENCE BACKGROUND Market power and regulation Jean Tirole is one of the most infuential economists of our time. He has made important theoretical research contributions in a number of areas, but most of all he has clarifed how to understand and regulate industries with a few powerful frms. Tirole is awarded this year’s prize for his analysis of market power and regulation. Regulation is difficult Which activities should be conducted as public services and which should be left to private frms is a question that is always relevant. Many governments have opened up public monopolies to private stakeholders. This has applied to industries such as railways, highways, water, post and telecom- munications – but also to the provision of schooling and healthcare. The experiences resulting from these privatizations have been mixed and it has often been more difcult than anticipated to get private frms to behave in the desired way. There are two main difculties. First, many markets are dominated by a few frms that all infuence prices, volumes and quality. Traditional economic theory does not deal with this case, known as an oligopoly, instead it presupposes a single monopoly or what is known as perfect competition. The second difculty is that the regulatory authority lacks information about the frms’ costs and the quality of the goods and services they deliver. This lack of knowledge often provides regulated frms with a natural advantage. Before Tirole In the 1980s, before Tirole published his frst work, research into regulation was relatively sparse, mostly dealing with how the government can intervene and control pricing in the two extremes of monopoly and perfect competition. -

The Future of Finance

THE TOULOUSE SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS MAGAZINE Living economics #16 SPRING THE FUTURE 2018 OF FINANCE Daniel Ershov on Johannes Hörner Ariel Pakes on Patrick Pouyanné the Google Play on how Waze uses why industrial on the energy Store its users organization matters challenge Editor�' message #16 Content� Looking New� & event� to the future 4 Appointments & prizes 5 Save the date Last year marked TSE’s 10th anniversary, a milestone in the long history of economics in Toulouse. 2017 also saw our endowment strengthened through the renewal of our Laboratoire d’Excellence status and an exciting new certification for our “CHESS” graduate school project - Challenges in Economics and Christian Gollier Quantitative Social Sciences. We are grateful for and proud of these strong signals of support which will help our institution tremendously. Researc� TSE wasn’t built in a day. It took more than 30 years for Jean- 6 Reducing search costs Jacques Laffont and the leading academic peers he convinced THE FUTURE Daniel Ershov to join him to accomplish his dream of building a world-class economics department in Toulouse with bright, intense academic OF FINANCE 8 Why would Waze life. We are lucky to be now living that dream, but our ambition send you off-track? for this new year does not waver. We want to aim higher Johannes Hörner and attract the very best talents to the south of France. Our Jean Tirole minds are focused on the future; our new building, now almost 16 Jean Tirole complete, will be another great asset in making our community one of the best Th inker� places in Europe to do research. -

Programme Booklet

Programme 6th Lindau Meeting on Economic Sciences 23 – 26 August 2017 MEETING APP TABLE OF CONTENTS WANT TO STAY UP TO DATE? Download the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings App. Available in Android and iTunes app stores. (“Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings”) Scientific Programme page 8 About the Meetings page 34 • Up-to-date programme info & details • Session abstracts Supporters page 38 • Ask questions during panel discussions • Participate in polls and surveys Maps page 46 • Interactive maps • Connect to other participants Good to Know page 54 • Social media integration Download the app (Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings) in Android, iTunes or Windows Phone app stores. Within the app, use the passphrase “marketpower” to download the guide for the 6th Lindau Meeting on Economic Sciences. 2 3 WELCOME WELCOME The 6th Lindau Meeting on Economic Sciences takes place during a climate With every meeting, we aim to further increase the opportunities of dia- of intense debate in society and science. Radical ideologies and re-emerging logue between laureates and young economists. This year, we are expand- separatist or nationalist sentiments add to a growing sense of insecurity ing formats of exchange into afternoon seminars: Selected economists will and isolation. Recent political decisions and their consequences are signs of have the opportunity to present their work to a group of laureates. Com- a global volatility. Further uncertainty is created by the trend of post-factual munication during the week will be improved by a meeting app that allows statements and science denial in public discourse. James J. Heckman gives up-to-date programme information. a possible response to this dilemma in a video on the future of economics: The Lindau Science Trail, a public exhibition project integrating science into “Empirical economics that’s grounded in solid data is a vaccine against this the Lindau city space, is a new addition to our outreach efforts as part of our post-truth world.” “Mission Education”. -

Macroeconomics 4

Macroeconomics IV Bocconi University Ph.D. in Economics Spring 2021 Instructor: Luigi Iovino Time: Th. 16:30 – 18:00 Email: [email protected] F.10:20 – 11:50 TA: Andrea Pasqualini Email: [email protected] Course description. This course is divided into three parts. In the first part, we will cover the workhorse New-Keynesian model. We will use this model to draw normative lessons for monetary policy, both with and without commitment of the Central Bank. We will also discuss the empirical evidence quantifying the importance of nominal rigidities. The second part of the course focuses on the effect of financial frictions on macroeconomic outcomes. Loosely speaking, financial frictions refer to the informational, behavioral, or insti- tutional features that constrain the flow of resources from savers to potential investors or con- sumers. This course introduces some of these frictions and analyzes their effect on investment, consumption, asset prices, financial crises, and business cycles. In the third part, we will study models with informational frictions. Starting from the seminal work of Lucas (1972) on money non-neutrality, the course will cover the business-cycle proper- ties of models with dispersed information and the social value of information. We will discuss (most of) the papers marked with an asterisk. The other papers are recom- mended to those who are interested in the topic. 1 The New Keynesian Model Theory * Jordi Gal´ı. Monetary policy, inflation, and the business cycle: an introduction to the new Keynesian framework and its applications. Princeton University Press, 2015 • Carl E Walsh. Monetary theory and policy. -

IO Reading List

Economics 257 – MGTECON 630 Fall 2020 Professor José Ignacio Cuesta [email protected] Professor Liran Einav [email protected] Professor Paulo Somaini [email protected] Industrial Organization I: Reading List I. Imperfect Competition: Background Bresnahan, Tim “Empirical Studies with Market Power,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, vol. II, chap. 17. Einav, Liran and Jonathan Levin. “Empirical Industrial Organization: A Progress Report,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(2), 145-162 (2010). Tirole, Jean. The Theory of Industrial Organization, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988. A. Test of Market Power Ashenfelter, O., and D. Sullivan, “Nonparametric Tests of Market Structure: An Application to the Cigarette Industry,” Journal of Industrial Economics 35, 483-498, (1989). Baker, J., and T. Bresnahan, “Estimating the residual demand curve facing a single firm,” International Journal of Industrial Organization 6(3), 283-300, (1988). Corts, K., “Conduct Parameters and the Measurement of Market Power,” Journal of Econometrics 88, 227-225, (1999). Genesove, D. and W. Mullin, “Testing Static Oligopoly Models: Conduct and Cost in the Sugar Industry, 1890-1914,” Rand Journal of Economics 29(2), 355-377, (1989). Stigler, G. “A Theory of Oligopoly,” The Journal of Political Economy, 72(1), 44-61, (1964) Sumner, D., “Measurement of Monopoly Behavior: An Application to the Cigarette Industry,” Journal of Political Economy 89, 1010-1019, (1981). Wolfram, C., “Measurement of Monopoly Behavior: An Application to the Cigarette Industry,” American Economic Review 89($), 805-826, (1999). B. Differentiated Products Anderson, S. P., A. de Palma, and J. F. Thisse, Discrete Choice Theory of Product Differentiation, Chapters 1-5, Cambridge: MIT Press, (1992). Caplin, A., and B. -

Letter in Le Monde

Letter in Le Monde Some of us ‐ laureates of the Nobel Prize in economics ‐ have been cited by French presidential candidates, most notably by Marine le Pen and her staff, in support of their presidential program with regards to Europe. This letter’s signatories hold a variety of views on complex issues such as monetary unions and stimulus spending. But they converge on condemning such manipulation of economic thinking in the French presidential campaign. 1) The European construction is central not only to peace on the continent, but also to the member states’ economic progress and political power in the global environment. 2) The developments proposed in the Europhobe platforms not only would destabilize France, but also would undermine cooperation among European countries, which plays a key role in ensuring economic and political stability in Europe. 3) Isolationism, protectionism, and beggar‐thy‐neighbor policies are dangerous ways of trying to restore growth. They call for retaliatory measures and trade wars. In the end, they will be bad both for France and for its trading partners. 4) When they are well integrated into the labor force, migrants can constitute an economic opportunity for the host country. Around the world, some of the countries that have been most successful economically have been built with migrants. 5) There is a huge difference between choosing not to join the euro in the first place and leaving it once in. 6) There needs to be a renewed commitment to social justice, maintaining and extending equality and social protection, consistent with France’s longstanding values of liberty, equality, and fraternity. -

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography

Τεύχος 53, Οκτώβριος-Δεκέμβριος 2019 | Issue 53, October-December 2019 ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη Nobel Prize in Economics Τα τεύχη δημοσιεύονται στον ιστοχώρο της All issues are published online at the Bank’s website Τράπεζας: address: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/trapeza/kepoe https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/the- t/h-vivliothhkh-ths-tte/e-ekdoseis-kai- bank/culture/library/e-publications-and- anakoinwseis announcements Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος. Κέντρο Πολιτισμού, Bank of Greece. Centre for Culture, Research and Έρευνας και Τεκμηρίωσης, Τμήμα Documentation, Library Section Βιβλιοθήκης Ελ. Βενιζέλου 21, 102 50 Αθήνα, 21 El. Venizelos Ave., 102 50 Athens, [email protected] Τηλ. 210-3202446, [email protected], Tel. +30-210-3202446, 3202396, 3203129 3202396, 3203129 Βιβλιογραφία, τεύχος 53, Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019, Bibliography, issue 53, Oct.-Dec. 2019, Nobel Prize Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη in Economics Συντελεστές: Α. Ναδάλη, Ε. Σεμερτζάκη, Γ. Contributors: A. Nadali, E. Semertzaki, G. Tsouri Τσούρη Βιβλιογραφία, αρ.53 (Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019), Βραβείο Nobel στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη 1 Bibliography, no. 53, (Oct.-Dec. 2019), Nobel Prize in Economics Πίνακας περιεχομένων Εισαγωγή / Introduction 6 2019: Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer 7 Μονογραφίες / Monographs ................................................................................................... 7 Δοκίμια Εργασίας / Working papers ...................................................................................... -

Competition and the Industrial Challenge for the Digital Age*

Competition and the Industrial Challenge for the Digital Age* Jean Tirole† April 3, 2020 Abstract: Tech giants’ dominance does not confront us with an unpalatable choice between laissez‐faire and populist interventions. The paper takes stock of available knowledge, considers desirable adaptations of regulation in the digital age, and draws some conclusions for policy reform. Keywords: regulation, divestiture, antitrust, industrial policy, contestability, mergers, data. JEL codes : D42, L1, L4, L5, L9. * I am grateful for extremely helpful comments to Erik Brynjolfsson, Judith Chevalier, Diane Coyle, Jacques Crémer, Andrei Hagiu, Massimo Motta, Patrick Rey, Paul Seabright, Alex White, Vanessa Zhang, and especially Fiona Scott‐ Morton and John van Reneen. This project received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 669217 ‐ ERC MARKLIM). The paper is written as a background piece for the IFS Deaton Review on “Inequalities in the Twenty‐First Century”, of which the author is a member of the panel. The evidence on increasing markups and their causes will be reviewed for the Deaton Review by John van Reenen. The dominance of tech giants is widely regarded as one of (a number of) drivers of the increase in top‐income inequality (for empirical evidence that correlations between measures of innovation and top income inequality at least partly reflect a causality from innovation to top income shares, see Aghion et al 2019). † Toulouse School of Economics (TSE) and Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse (IAST). 1 1. Introduction The initial enthusiasm for the ongoing technological revolution has recently given way to a global “techlash”. -

Prize in Economics

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science is set to be announced on PRIZE IN Monday. The contenders include Jean Tirole, Bengt Holmstrom, Oliver Hart, Robert Barro, Paul Romer, Avinash Dixit, Angus Deaton, Lars Peter Hansen, NOBELECONOMICS William Baumol, Robert Shiller, Richard Thaler, Andrei Shleifer, William Nordhaus, Douglas Diamond, Alan Krueger, David Card, Joshua Angrist, Jerry THE LAUREATES Hausman and Eugene Fama. A look at the winners through the last 10 years 2012 2011 Alvin E Roth LLOYD S SHAPLEY Born: 18 December, 1951, US Born: 2 June, 1923, US Affiliation at the time of Affiliation at the time the award: Harvard of the award: University, Cambridge, MA, University of USA, Harvard Business California, Los School, Boston, MA, USA Angeles, CA, US For the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design Thomas J Sargent 2010 2009 Born: 1943, US Affiliation at the time of the Elinor Ostrom Peter A Diamond award: New York University, Born: 29 April, 1940, US Born: 7 August, 1933, US New York, NY, US Affiliation at the Affiliation at the time of the award: Christopher A Sims time of the Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, award: US, Arizona State University, Tempe, Born: 1942, US Massachusetts AZ, US Affiliation at the Institute of For her analysis of economic governance, especially the commons time of the Technology award: (MIT), Cambridge, Oliver E Williamson Princeton MA, US Born: 27 September, 1932, US University, Affiliation at the time of the award: Princeton, NJ, Dale T Mortensen University of California, -

The BBVA Foundation Distinguishes the Economist Daron Acemoglu for Establishing the Key Role of Institutions in Fostering Economic Development

www.fbbva.es BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Economics, Finance and Management The BBVA Foundation distinguishes the economist Daron Acemoglu for establishing the key role of institutions in fostering economic development Contrary to the hypothesis of geographic determinism, his research into the development of former colonies uncovered empirical evidence that quality of institutions was a key driver of economic development Acemoglu developed the concepts of inclusive institutions, which contribute to prosperity, and extractive institutions, which hold back development to the detriment of most of society He has also researched into labor market differences, explaining the seeming paradox that an increased supply of skilled workers does not translate as lower wages Madrid, February 21, 2017.- The BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the Economics, Finance and Management category goes, in this ninth edition, to Daron Acemoglu, a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), for identifying the causal impact of institutions on economic development, through an innovative mix of theoretical and empirical analysis “that has been influential not only in economics, but also in political science, history, and social sciences more broadly.” Jury secretary Manuel Arellano describes Acemoglu as “outstanding in his ability to combine a prolific output of exceptional quality in diverse research fields, with major contributions in each, with an approach that is at once empirical and theoretical.” The new laureate, he continues, “has helped elucidate the determinants of long- term economic development, with particular emphasis on the important role played by institutions and social organization. Acemoglu’s novel contribution was to deploy a strategy that led him to empirical evidence identifying the causal effect of institutions on development.” His research has opened up a whole new field where researchers can measure and quantify the impact of the institutional model on a society’s development at different scales. -

Policy and Choice: Public Finance Through the Lens of Behavioral

advance Praise For POLICY and CHOICE Mullai Congdon • Kling “Policy and Choice is a must-read for students of public finance. If you want to learn N William J. Congdon is a research director in Traditional public ἀnance provides a powerful how the emerging field of behavioral economics can help lead to better policy, there is atha the Brookings Institution’s Economic Studies framework for policy analysis, but it relies on a nothing better.” program, where he studies how best to apply model of human behavior that the new science , Harvard University, former chairman of the President’s Council of N. GreGory MaNkiw N behavioral economics to public policy. Economic Advisers, and author of Principles of Economics of behavioral economics increasingly calls into question. In Policy and Choice economists Jeἀrey R. Kling is the associate director for William Congdon, Jeffrey Kling, and Sendhil economic analysis at the Congressional Budget “This fantastic volume will become the standard reference for those interested in understanding the impact of behavioral economics on government tax and spending Mullainathan argue that public ἀnance not only Office, where he contributes to all aspects of the POLICY policies. The authors take a stream of research which had highlighted particular can incorporate many lessons of behavioral eco- agency’s analytic work. He is a former deputy ‘nudges’ and turn it into a comprehensive framework for thinking about policy in a nomics but also can serve as a solid foundation director of Economic Studies at Brookings. more realistic world where psychology is incorporated into economic decisionmaking. from which to apply insights from psychology Sendhil Mullainathan is a professor of This excellent book will be widely used and cited.” to questions of economic policy. -

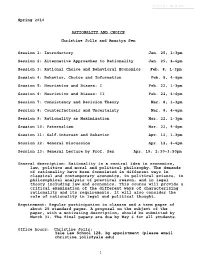

Rationality and Choice

Spring 2010 RATIONALITY AND CHOICE Christine Jolls and Amartya Sen Session 1: Introductory Jan. 25, 1-3pm Session 2: Alternative Approaches to Rationality Jan. 25, 4-6pm Session 3: Rational Choice and Behavioral Economics Feb. 8, 1-3pm Session 4: Behavior, Choice and Information Feb. 8, 4-6pm Session 5: Heuristics and Biases: I Feb. 22, 1-3pm Session 6: Heuristics and Biases: II Feb. 22, 4-6pm Session 7: Consistency and Decision Theory Mar. 8, 1-3pm Session 8: Counterfactuals and Uncertainty Mar. 8, 4-6pm Session 9: Rationality as Maximization Mar. 22, 1-3pm Session 10: Paternalism Mar. 22, 4-6pm Session 11: Self-interest and Behavior Apr. 12, 1-3pm Session 12: General Discussion Apr. 12, 4-6pm Session 13: General Lecture by Prof. Sen Apr. 19, 2:30-3:50pm General description: Rationality is a central idea in economics, law, politics and moral and political philosophy. The demands of rationality have been formulated in different ways in classical and contemporary economics, in political science, in philosophical analysis of practical reason, and in legal theory including law and economics. This course will provide a critical examination of the different ways of characterizing rationality and its requirements. It will also consider the role of rationality in legal and political thought. Requirement: Regular participation in classes and a term paper of about 25 standard pages. A proposal on the subject of the paper, with a motivating description, should be submitted by March 31. The final papers are due by May 6 for all students. Office hours: Christine Jolls: Yale Law School 128, by appointment (please email [email protected]) 1 Amartya Sen: Mondays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, no appointment needed Tuesdays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, by appointment (please call 5-1871) General readings: The following books may be used as general reference: Richard Thaler, Quasi Rational Economics.