Growth and Survival of Nestlings in a Population of Red-Crowned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand's Genetic Diversity

1.13 NEW ZEALAND’S GENETIC DIVERSITY NEW ZEALAND’S GENETIC DIVERSITY Dennis P. Gordon National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie, Wellington 6022, New Zealand ABSTRACT: The known genetic diversity represented by the New Zealand biota is reviewed and summarised, largely based on a recently published New Zealand inventory of biodiversity. All kingdoms and eukaryote phyla are covered, updated to refl ect the latest phylogenetic view of Eukaryota. The total known biota comprises a nominal 57 406 species (c. 48 640 described). Subtraction of the 4889 naturalised-alien species gives a biota of 52 517 native species. A minimum (the status of a number of the unnamed species is uncertain) of 27 380 (52%) of these species are endemic (cf. 26% for Fungi, 38% for all marine species, 46% for marine Animalia, 68% for all Animalia, 78% for vascular plants and 91% for terrestrial Animalia). In passing, examples are given both of the roles of the major taxa in providing ecosystem services and of the use of genetic resources in the New Zealand economy. Key words: Animalia, Chromista, freshwater, Fungi, genetic diversity, marine, New Zealand, Prokaryota, Protozoa, terrestrial. INTRODUCTION Article 10b of the CBD calls for signatories to ‘Adopt The original brief for this chapter was to review New Zealand’s measures relating to the use of biological resources [i.e. genetic genetic resources. The OECD defi nition of genetic resources resources] to avoid or minimize adverse impacts on biological is ‘genetic material of plants, animals or micro-organisms of diversity [e.g. genetic diversity]’ (my parentheses). -

Eastern Rosella (Platycercus Eximius)

Eastern rosella (Platycercus eximius) Class: Aves Order: Psittaciformes Family: Psittaculidae Characteristics: The Eastern rosella averages 30 cm (12 in) in length and 99gm (3.5oz) in weight. With a red head and white cheeks, the upper breast is red and the lower breast is yellow fading to pale green over the abdomen. The feathers of the back and shoulders are black, and have yellowish or greenish margins giving rise to a scalloped appearance that varies slightly between three subspecies and the sexes. The wings and lateral tail feathers are bluish while the tail is dark green. Range & Habitat: Behavior: Like most parrots, Eastern rosellas are cavity nesters, generally Eastern Australia down to nesting high in older large trees in forested areas. They enjoy bathing in Tasmania in wooded country, puddles of water in the wild and in captivity and frequently scratch their open forests, woodlands and heads with the foot behind the wing. Typical behavior also includes an parks. Nests in tree cavities, undulating flight, strutting by the male, and tail wagging during various stumps or posts. displays such as courting, and a high-pitched whistle consisting of sharp notes repeated rapidly in quick succession. Reproduction: Breeding season is influenced by rain and location. Courting male bows while sounding out mating call followed by mutual feeding and then mating. Female alone incubates eggs while male bring food. 2-9 eggs will hatch in 18 - 20 days. Hatchlings are ready to leave the nest in about 5 weeks but may stay with their parents for several months unless there is another mating. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Population Size, Provisioning Frequency, Flock Size and Foraging

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Naturalis Population size, provisioning frequency, flock size and foraging range at the largest known colony of Psittaciformes: the Burrowing Parrots of the north-eastern Patagonian coastal cliffs Juan F. MaselloA,B,C,G, María Luján PagnossinD, Christina SommerE and Petra QuillfeldtF AInstitut für Ökologie, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Germany. BEcology of Vision Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, UK. CMax Planck Institute for Ornithology, Vogelwarte Radolfzell, Schlossallee 2, D-78315 Radolfzell, Germany. DFacultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina. EInstitut für Biologie/Verhaltensbiologie, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany. FSchool of Biosciences, Cardiff University, UK. GCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract.We here describe the largest colony of Burrowing Parrots (Cyanoliseus patagonus), located in Patagonia, Argentina. Counts during the 2001–02 breeding season showed that the colony extended along 9 km of a sandstone cliff facing the Altantic Ocean, in the province of Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina, and contained 51412 burrows, an estimated 37527 of which were active. To our knowledge, this is largest known colony of Psittaciformes. Additionally, 6500 Parrots not attending nestlings were found to be associated with the colony during the 2003–04 breeding season. We monitored activities at nests and movements between nesting and feeding areas. Nestlings were fed 3–6 times daily. Adults travelled in flocks of up to 263 Parrots to the feeding grounds in early mornings; later in the day, they flew in smaller flocks, making 1–4 trips to the feeding grounds. -

Foraging Ecology of the World's Only

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. FORAGING ECOLOGY OF THE WORLD’S ONLY POPULATION OF THE CRITICALLY ENDANGERED TASMAN PARAKEET (CYANORAMPHUS COOKII), ON NORFOLK ISLAND A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology at Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand. Amy Waldmann 2016 The Tasman parakeet (Cyanoramphus cookii) Photo: L. Ortiz-Catedral© ii ABSTRACT I studied the foraging ecology of the world’s only population of the critically endangered Tasman parakeet (Cyanoramphus cookii) on Norfolk Island, from July 2013 to March 2015. I characterised, for the first time in nearly 30 years of management, the diversity of foods consumed and seasonal trends in foraging heights and foraging group sizes. In addition to field observations, I also collated available information on the feeding biology of the genus Cyanoramphus, to understand the diversity of species and food types consumed by Tasman parakeets and their closest living relatives as a function of bill morphology. I discuss my findings in the context of the conservation of the Tasman parakeet, specifically the impending translocation of the species to Phillip Island. I demonstrate that Tasman parakeets have a broad and flexible diet that includes seeds, fruits, flowers, pollen, sori, sprout rhizomes and bark of 30 native and introduced plant species found within Norfolk Island National Park. Dry seeds (predominantly Araucaria heterophylla) are consumed most frequently during autumn (81% of diet), over a foraging area of ca. -

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Two Endangered Neotropical Parrots Inform in Situ and Ex Situ Conservation Strategies

diversity Article Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Two Endangered Neotropical Parrots Inform In Situ and Ex Situ Conservation Strategies Carlos I. Campos 1 , Melinda A. Martinez 1, Daniel Acosta 1, Jose A. Diaz-Luque 2, Igor Berkunsky 3 , Nadine L. Lamberski 4, Javier Cruz-Nieto 5 , Michael A. Russello 6 and Timothy F. Wright 1,* 1 Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] (C.I.C.); [email protected] (M.A.M.); [email protected] (D.A.) 2 Fundación CLB (FPCILB), Estación Argentina, Calle Fermín Rivero 3460, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia; [email protected] 3 Instituto Multidisciplinario sobre Ecosistemas y Desarrollo Sustenable, CONICET-Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Tandil 7000, Argentina; [email protected] 4 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, San Diego, CA 92027, USA; [email protected] 5 Organización Vida Silvestre A.C. (OVIS), San Pedro Garza Garciá 66260, Mexico; [email protected] 6 Department of Biology, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, BC V1V 1V7, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A key aspect in the conservation of endangered populations is understanding patterns of Citation: Campos, C.I.; Martinez, genetic variation and structure, which can provide managers with critical information to support M.A.; Acosta, D.; Diaz-Luque, J.A.; evidence-based status assessments and management strategies. This is especially important for Berkunsky, I.; Lamberski, N.L.; species with small wild and larger captive populations, as found in many endangered parrots. We Cruz-Nieto, J.; Russello, M.A.; Wright, used genotypic data to assess genetic variation and structure in wild and captive populations of T.F. -

Pb) Exposure in Populations of a Wild Parrot (Kea Nestor Notabilis

56 AvailableNew on-lineZealand at: Journal http://www.newzealandecology.org/nzje/ of Ecology, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2012 Anthropogenic lead (Pb) exposure in populations of a wild parrot (kea Nestor notabilis) Clio Reid1, Kate McInnes1,*, Jennifer M. McLelland2 and Brett D. Gartrell2 1Research and Development Group, Department of Conservation, PO Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand 2New Zealand Wildlife Health Centre, Institute of Veterinary, Animal and Biomedical Sciences, Massey University, Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published on-line: 9 December 2011 Abstract: Kea (Nestor notabilis), large parrots endemic to hill country areas of the South Island, New Zealand, are subject to anthropogenic lead (Pb) exposure in their environment. Between April 2006 and June 2009 kea were captured in various parts of their range and samples of their blood were taken for blood lead analysis. All kea (n = 88) had been exposed to lead, with a range in blood lead concentrations of 0.014 – 16.55 μmol L–1 (mean ± SE, 1.11 ± 0.220 μmol L–1). A retrospective analysis of necropsy reports from 30 kea was also carried out. Of these, tissue lead levels were available for 20 birds, and 11 of those had liver and/or kidney lead levels reported to cause lead poisoning in other avian species. Blood lead levels for kea sampled in populated areas (with permanent human settlements) were significantly higher (P < 0.001) than those in remote areas. Sixty-four percent of kea sampled in populated areas had elevated blood lead levels (> 0.97 μmol L–1, the level suggestive of lead poisoning in parrots), and 22% had levels > 1.93 μmol L–1 – the level diagnostic of lead poisoning in parrots. -

Science for Saving Species Research Findings Factsheet Project 4.2

Science for Saving Species Research findings factsheet Project 4.2 Assessing the impacts of invasive species: Hollow-nesting birds in Tasmania In brief Background Predicting the impacts of invasive Invasive alien birds are found explore the known and theoretical species is difficult at large spatial across many areas of Australia. interaction network between the scales. This is because the interactions Many of these introduced birds cavity breeding birds in Tasmania, between invasive species and native use cavities, an important breeding and to identify which native species species vary across different species, resource for cavity nesting species. are likely impacted by the addition between different locations, over In Tasmania alone there are 27 of non-native species. time and in relation to other pressures species of hollow-nesting birds, We discovered that, overall, such as habitat loss, extensive fires, including three threatened species native hollow-nesting species climatic events and drought. and seven invasive hollow-nesting are likely facing increased levels bird species. The logging of big old Given that conservation and of competition for nesting sites trees with cavities and the addition management work is almost always as a result of non-native species of invasive species has likely led conducted under limited budgets and introductions. Such competition to increased competition over time, being able to quantify where is likely to decrease breeding the limited resource. However, and when invasive species are having opportunities for native species, the impact of most of these a significant impact on local species including some of Tasmania’s invasive species has not been is vital for effectively managing and threatened and endemic species. -

New Caledonia, Fiji & Vanuatu

Field Guides Tour Report Part I: New Caledonia Sep 5, 2011 to Sep 15, 2011 Phil Gregory The revamped tour was a little later this year and it seemed to make some things a bit easier, note how well we did with the rare Crow Honeyeater, and Kagu was as ever a standout. One first-year bird was rewarded with a nice juicy scorpion that our guide found, and this really is a fabulous bird to see, another down on Harlan's famiy quest, too, as an added bonus to what is a quite unique bird. Cloven-feathered Dove was also truly memorable, and watching one give that strange, constipated hooting call was fantastic and this really is one of the world's best pigeons. Air Calin did their best to make life hard with a somewhat late flight to Lifou, and I have to say the contrast with the Aussie pilots in Vanuatu was remarkable -- these French guys must still be learning as they landed the ATR 42's so hard and had to brake so fiercely! Still, it all worked out and the day trip for the Ouvea Parakeet worked nicely, whilst the 2 endemic white-eyes on Lifou were got really early for once. Nice food, an interesting Kanak culture, with a trip to the amazing Renzo Piano-designed Tjibaou Cultural Center also feasible this The fantastic Kagu, star of the tour! (Photo by guide Phil year, and a relaxed pace make this a fun birding tour with some Gregory) terrific endemic birds as a bonus. My thanks to Karen at the Field Guides office for hard work on the complex logistics for this South Pacific tour, to the very helpful Armstrong at Arc en Ciel, Jean-Marc at Riviere Bleue, and to Harlan and Bart for helping me with my bags when I had a back problem. -

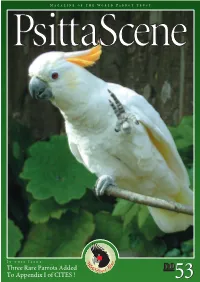

Three Rare Parrots Added to Appendix I of CITES !

PsittaScene In this Issue: Three Rare Parrots Added To Appendix I of CITES ! Truly stunning displays PPsittasitta By JAMIE GILARDI In mid-October I had the pleasure of visiting Bolivia with a group of avid parrot enthusiasts. My goal was to get some first-hand impressions of two very threatened parrots: the Red-fronted Macaw (Ara rubrogenys) and the Blue-throated Macaw (Ara SceneScene glaucogularis). We have published very little about the Red-fronted Macaw in PsittaScene,a species that is globally Endangered, and lives in the foothills of the Andes in central Bolivia. I had been told that these birds were beautiful in flight, but that Editor didn't prepare me for the truly stunning displays of colour we encountered nearly every time we saw these birds. We spent three days in their mountain home, watching them Rosemary Low, fly through the valleys, drink from the river, and eat from the trees and cornfields. Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, Since we had several very gifted photographers on the trip, I thought it might make a TR27 4HB, UK stronger impression on our readers to present the trip in a collection of photos. CONTENTS Truly stunning displays................................2-3 Gold-capped Conure ....................................4-5 Great Green Macaw ....................................6-7 To fly or not to fly?......................................8-9 One man’s vision of the Trust..................10-11 Wild parrot trade: stop it! ........................12-15 Review - Australian Parrots ..........................15 PsittaNews ....................................................16 Review - Spix’s Macaw ................................17 Trade Ban Petition Latest..............................18 WPT aims and contacts ................................19 Parrots in the Wild ........................................20 Mark Stafford Below: A flock of sheep being driven Above: After tracking the Red-fronts through two afternoons, we across the Mizque River itself by a found that they were partial to one tree near a cornfield - it had sprightly gentleman. -

Success of Translocations of Red-Fronted Parakeets

Conservation Evidence (2010) 7, 21-26 www.ConservationEvidence.com Success of translocations of red-fronted parakeets Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae novaezelandiae from Little Barrier Island (Hauturu) to Motuihe Island, Auckland, New Zealand Luis Ortiz-Catedral* & Dianne H. Brunton Ecology and Conservation Group, Institute of Natural Sciences, Massey University, Private Bag 102-904, Auckland, New Zealand * Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY The red-fronted parakeet Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae is a vulnerable New Zealand endemic with a fragmented distribution, mostly inhabiting offshore islands free of introduced mammalian predators. Four populations have been established since the 1970s using captive-bred or wild-sourced individuals translocated to islands undergoing ecological restoration. To establish a new population in the Hauraki Gulf, North Island, a total of 31 parakeets were transferred from Little Barrier Island (Hauturu) to Motuihe Island in May 2008 and a further 18 in March 2009. Overall 55% and 42% of individuals from the first translocation were confirmed alive at 30 and 60 days post-release, respectively. Evidence of nesting and unassisted dispersal to a neighbouring island was observed within a year of release. These are outcomes are promising and indicate that translocation from a remnant wild population to an island free of introduced predators is a useful conservation tool to expand the geographic range of red-fronted parakeets. BACKGROUND mammalian predators and undergoing ecological restoration, Motuihe Island. The avifauna of New Zealand is presently considered to be the world’s most extinction- Little Barrier Island (c. 3,000 ha; 36 °12’S, prone (Sekercioglu et al. 2004). Currently, 77 175 °04’E) lies in the Hauraki Gulf of approximately 280 extant native species are approximately 80 km north of Auckland City considered threatened of which approximately (North Island), and is New Zealand’s oldest 30% are listed as Critically Endangered wildlife reserve, established in 1894 (Cometti (Miskelly et al. -

Of Parrots 3 Other Major Groups of Parrots 16

ONE What are the Parrots and Where Did They Come From? The Evolutionary History of the Parrots CONTENTS The Marvelous Diversity of Parrots 3 Other Major Groups of Parrots 16 Reconstructing Evolutionary History 5 Box 1. Ancient DNA Reveals the Evolutionary Relationships of the Fossils, Bones, and Genes 5 Carolina Parakeet 19 The Evolution of Parrots 8 How and When the Parrots Diversified 25 Parrots’ Ancestors and Closest Some Parrot Enigmas 29 Relatives 8 What Is a Budgerigar? 29 The Most Primitive Parrot 13 How Have Different Body Shapes Evolved in The Most Basal Clade of Parrots 15 the Parrots? 32 THE MARVELOUS DIVERSITY OF PARROTS The parrots are one of the most marvelously diverse groups of birds in the world. They daz- zle the beholder with every color in the rainbow (figure 3). They range in size from tiny pygmy parrots weighing just over 10 grams to giant macaws weighing over a kilogram. They consume a wide variety of foods, including fruit, seeds, nectar, insects, and in a few cases, flesh. They produce large repertoires of sounds, ranging from grating squawks to cheery whistles to, more rarely, long melodious songs. They inhabit a broad array of habitats, from lowland tropical rainforest to high-altitude tundra to desert scrubland to urban jungle. They range over every continent but Antarctica, and inhabit some of the most far-flung islands on the planet. They include some of the most endangered species on Earth and some of the most rapidly expanding and aggressive invaders of human-altered landscapes. Increasingly, research into the lives of wild parrots is revealing that they exhibit a corresponding variety of mating systems, communication signals, social organizations, mental capacities, and life spans.