Anthem for Jersey: Music, Media and Politics in an Island Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREHISTORIC JERSEY People and Climate of the Ice Age

PREHISTORIC JERSEY People and climate of the Ice Age Lesson plan Fact sheets Quiz sheets Story prompts Picture sheets SUPPORTED BY www.jerseyheritage.org People and climate of the Ice Age .............................................................................................................................................................................. People and climate of plan the Ice Age Lesson Introduction Lesson Objectives Tell children that they are going to be finding To understand that the Ice out about the very early humans that lived during Age people were different the Ice Age and the climate that they lived in. species. Explain about the different homo species of To understand there are two main early humans we study, early humans and what evidence there is for this. Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens. Discuss what a human is and the concept of To develop the appropriate evolution. use of historical terms. To understand that Jersey has Ask evidence of both Neanderthals How might people in the Ice Age have lived? and Early Homo Sapiens on the Where did they live? island. Who did they live with? How did they get food and what clothes did they Expected Outcomes wear? Why was it called the Ice Age? All children will be able to identify two different sets of What did the landscape look like? people living in the Ice Age. Explain that the artefacts found in Jersey are Most children will able to tools made by people and evidence left by the identify two different sets of early people which is how they can tell us about people living in the Ice Age and the Ice Age. describe their similarities and differences. Some children will describe two different sets of people Whole Class Work living in the Ice Age, describe Read and discuss the page ‘People of the their similarities and differences Ice Age’ which give an overview of the Ice Age and be able to reflect on the people and specifically the Neanderthals and evolution of people according Homo Sapiens. -

The Jersey Heritage Answersheet

THE JERSEY HERITAGE Monuments Quiz ANSWERSHEET 1 Seymour Tower, Grouville Seymour Tower was built in 1782, 1¼ miles offshore in the south-east corner of the Island. Jersey’s huge tidal range means that the tower occupies the far point which dries out at low tide and was therefore a possible landing place for invading troops. The tower is defended by musket loopholes in the walls and a gun battery at its base. It could also provide early warning of any impending attack to sentries posted along the shore. 2 Faldouet Dolmen, St Martin This megalithic monument is also known as La Pouquelaye de Faldouët - pouquelaye meaning ‘fairy stones’ in Jersey. It is a passage grave built in the middle Neolithic period, around 4000 BC, the main stones transported here from a variety of places up to three miles away. Human remains were found here along with finds such as pottery vessels and polished stone axes. 3 Cold War Bunker, St Helier A German World War II bunker adapted for use during the Cold War as Jersey’s Civil Emergency Centre and Nuclear Monitoring Station. The building includes a large operations room and BBC studio. 4 Statue of King George V in Howard Davis Park Bronze statue of King George V wearing the robes of the Sovereign of the Garter. Watchtower, La Coupe Point, St Martin 5 On the highest point of the headland is a small watchtower built in the early 19th century and used by the Royal Navy as a lookout post during the Napoleonic wars. It is sturdily constructed of mixed stone rubble with a circular plan and domed top in brick. -

Grouville Gazettegazette an Independent Glimpse of Life in Our Parish Autumn 2014 Volume 12 Issue 3 Printed on Paper from Sustainable Resources

Grouville GazetteGazette An independent glimpse of life in our parish Autumn 2014 Volume 12 Issue 3 Printed on paper from sustainable resources. What Next for Grouville? GG The magnificent Grouville 50th Anniversary float in all its glory! Perhaps we should have given this issue of the Grouville issue comes out so we start the general election period. Gazette the headline “What Happened to Summer?” Therefore, in case there are more candidates than the when we were enjoying a beautiful period of sun and hot joint announcement that our Connétable and Deputy are weather as we moved towards the Battle of Flowers - and standing for office, politics is also off the menu. Most then it all changed. Nevertheless, our wonderful float got importantly the changes to how you can vote are the Agnes Pallot Memorial Cup and you can see the explained on page 29. reason why above and in our centre pages. It was a great This issue therefore focuses principally on community, design, in a year of many equally stunning designs. That with articles about the commemoration of the start of said, it was our 50th anniversary and a shame we did not World War 1 on pages 3, 8 and 27 and a great article by reap the reward for everyone’s hard work. Nick Querée on page 12 about his trip last year to help There are changes in this issue with no fashion article people in Zambia improve their eyesight. In reality this and no politics. We could not resist the lovely article on issue focuses on what Grouville is all about; a great page 14 telling of Grouville School’s Victorian Day, but community led by caring and experienced people. -

The Story of New Jersey

THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY HAGAMAN THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Examination Copy THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY (1948) A NEW HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY is for use in the intermediate grades. A thorough story of the Middle Atlantic States is presented; the context is enriohed with illustrations and maps. THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY begins with early Indian Life and continues to present day with glimpses of future growth. Every aspect from mineral resources to vac-| tioning areas are discussed. 160 pages. Vooabulary for 4-5 Grades. List priceJ $1.28 Net price* $ .96 (Single Copy) (5 or more, f.o.b. i ^y., point of shipment) i^c' *"*. ' THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Linooln, Nebraska ..T" 3 6047 09044948 8 lererse The Story of New Jersey BY ADALINE P. HAGAMAN Illustrated by MARY ROYT and GEORGE BUCTEL The University Publishing Company LINCOLN NEW YORK DALLAS KANSAS CITY RINGWOOD PUBLIC LIBRARY 145 Skylands Road Ringwood, New Jersey 07456 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW.JERSEY IN THE EARLY DAYS Before White Men Came ... 5 Indian Furniture and Utensils 19 Indian Tribes in New Jersey 7 Indian Food 20 What the Indians Looked Like 11 Indian Money 24 Indian Clothing 13 What an Indian Boy Did... 26 Indian Homes 16 What Indian Girls Could Do 32 THE WHITE MAN COMES TO NEW JERSEY The Voyage of Henry Hudson 35 The English Take New Dutch Trading Posts 37 Amsterdam 44 The Colony of New The English Settle in New Amsterdam 39 Jersey 47 The Swedes Come to New New Jersey Has New Jersey 42 Owners 50 PIONEER DAYS IN NEW JERSEY Making a New Home 52 Clothing of the Pioneers .. -

48 St Saviour Q3 2020.Pdf

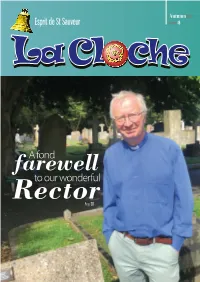

Autumn2020 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 48 farewellA fond Rectorto our wonderful Page 30 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Autumn 2020 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 From the Editor Featured Back on Track! articles La Cloche is back on track and we have a full magazine. There are some poems by local From the Constable poets to celebrate Liberation and some stories from St Saviour residents who were in Jersey when the Liberation forces arrived on that memorable day, 9th May 1945. It is always enlightening to read and hear of others’ stories from the Occupation and Liberation p4 of Jersey during the 1940s. Life was so very different then, from now, and it is difficult for us to imagine what life was really like for the children and adults living at that time. Giles Bois has submitted a most interesting article when St Saviour had to build a guardhouse on the south coast. The Parish was asked to help Grouville with patrolling Liberation Stories the coast looking for marauders and in 1690 both parishes were ordered to build a guardhouse at La Rocque. This article is a very good read and the historians among you will want to rush off to look for our Guardhouse! Photographs accompany the article to p11 illustrate the building in the early years and then later development. St Saviour Battle of Flowers Association is managing to keep itself alive with a picnic in St Paul’s Football Club playing field. They are also making their own paper flowers in different styles and designs; so please get in touch with the Association Secretary to help with Forever St Saviour making flowers for next year’s Battle. -

The Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey's

The Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey’s National and International Identity Interim Findings Report 1 Foreword Avant-propos What makes Jersey special and why does that matter? Those simple questions, each leading on to a vast web of intriguing, inspiring and challenging answers, underpin the creation of this report on Jersey’s identity and how it should be understood in today’s world, both in the Island and internationally. The Island Identity Policy Development Board is proposing for consideration a comprehensive programme of ways in which the Island’s distinctive qualities can be recognised afresh, protected and celebrated. It is the board’s belief that success in this aim must start with a much wider, more confident understanding that Jersey’s unique mixture of cultural and constitutional characteristics qualifies it as an Island nation in its own right. An enhanced sense of national identity will have many social and cultural benefits and reinforce Jersey’s remarkable community spirit, while a simultaneously enhanced international identity will protect its economic interests and lead to new opportunities. What does it mean to be Jersey in the 21st century? The complexity involved in providing any kind of answer to this question tells of an Island full of intricacy, nuance and multiplicity. Jersey is bursting with stories to tell. But none of these stories alone can tell us what it means to be Jersey. In light of all this complexity why take the time, at this moment, to investigate the different threads of what it means to be Jersey? I would, at the highest level, like to offer four main reasons: First, there is a profound and almost universally shared sense that what we have in Jersey is special. -

Dear Parents Tion Highlighted the Talent, Imagination and Ambition That Runs Deep in Year 7

QLearning to be yourNews best - through excellence and enjoyment Year 7, also new to Les Quennevais have settled in superbly. Their outstanding Transition Project Exhibi- Dear Parents tion highlighted the talent, imagination and ambition that runs deep in Year 7. Some of their projects are Welcome to our first edition of now on display at the Education Department at the ‘Q News’ - our way of collating request of the Education Minister. It is right that the a formal snapshot of ‘life’ at Les work of our students should be shared as an example Quennevais School each term to inspire and remind those leading Education in the to share with you all. Time Island of the creativity of our young people. passes so quickly at Les Quen- nevais and this edition is November was a month of great celebration begin- bursting with many of the ning with the Planning Committee’s approval of the things we have achieved application for a new Les Quennevais School building. during a very hectic but hugely This marked the end of a very long and at times very successful Autumn term. be worthwhile and as we begin 2018 I know I will not At the time of writing we are in be alone when driving past the site chosen, eagerly the midst of another ‘Christmas Jumper Day!’ The monitoring the project develop over time. I promise school is enlivened with festive spirit and of course you all it is going to be something quite amazing. Thank you for all the support we have received, lengths to raise funds for “Save the Children”, one of particularly from students past and present and the many international and local charities Les Quenne- parents in securing a public voice in support of the vais School supports throughout the year. -

States of Jersey Jersey Future Hospital

STATES OF JERSEY JERSEY FUTURE HOSPITAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT – SOCIO-ECONOMICS 14 SOCIO-ECONOMICS................................................................................................................ 14-1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 14-1 REVIEW OF PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................................. 14-1 LEGISLATION , POLICY CONTEXT AND GUIDANCE ................................................................................................ 14-1 CONSULTATION ............................................................................................................................................... 14-5 METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................................................. 14-6 LIMITATIONS AND ASSUMPTIONS ...................................................................................................................... 14-9 ECONOMIC PROFILE ........................................................................................................................................ 14-9 POPULATION AND LABOUR MARKET CONDITIONS ............................................................................................. 14-14 DESIGN MITIGATION ..................................................................................................................................... -

Sporting Events 2015 Date Sport Event Venue 26 Dec 2014 – 5 Jan Ice Hockey 2015 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships Air Canada Centre, Toronto Bell Centre, Montreal

Sheet2 Sporting Events 2015 Date Sport Event Venue 26 Dec 2014 – 5 Jan Ice hockey 2015 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships Air Canada Centre, Toronto Bell Centre, Montreal 4 Jan – 10 Jan Ice hockey 2015 IIHF World Women's U18 Championship – Division I Vaujany, France 4 Jan – 10 Jan Tennis 2015 Hopman Cup Perth, Australia 4 Jan – 17 Jan Rallying 2015 Dakar Rally Buenos Aires, Argentina 5 Jan – 12 Jan Ice hockey 2015 IIHF World Women's U18 Championship Buffalo, United States 10 Jan Formula E 2015 Buenos Aires ePrix Argentine 15 Jan – 25 Jan Snowboarding FIS Snowboarding World Championships 2015 Kreischberg, Austria 15 Jan –25 Jan Freestyle skiing FIS Freestyle World Ski Championships 2015 Kreischberg, Austria 15 Jan – 1 Feb Handball 2015 World Men's Handball Championship Qatar 16 Jan – 17 Jan Luge 2015 FIL Junior World Luge Championships Lillehammer, Norway 19 Jan – 25 Jan Ice hockey 2015 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships – Division III Dunedin, New Zealand 19 Jan – 25 Jan Ice hockey 2015 IIHF World Women's U18 Championship – Division I Qualification Katowice, Poland 19 Jan –1 Feb Tennis 2015 Australian Open Melbourne Park in Melbourne, Australia 22 Jan – 1 Feb Nordic skiing 2015 IPC Biathlon and Cross-Country Skiing World Championships Cable, Wisconsin United states 24 Jan – 1 Feb Multi-sport 2015 Winter Universiade (co-host with Spain) Granada, Spain 25 Jan – 15 Nov Rallying 2015 World Rally Championship season Europe, North and South America and Australia 31 Jan – 1 Feb Cyclo-cross 2015 UCI Cyclo-cross World Championships Tabor -

R.76/2021 the Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey’S National and International Identity

R.76/2021 The Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey’s National and International Identity Interim Findings Report 1 Foreword Avant-propos What makes Jersey special and why does that matter? Those simple questions, each leading on to a vast web of intriguing, inspiring and challenging answers, underpin the creation of this report on Jersey’s identity and how it should be understood in today’s world, both in the Island and internationally. The Island Identity Policy Development Board is proposing for consideration a comprehensive programme of ways in which the Island’s distinctive qualities can be recognised afresh, protected and celebrated. It is the board’s belief that success in this aim must start with a much wider, more confident understanding that Jersey’s unique mixture of cultural and constitutional characteristics qualifies it as an Island nation in its own right. An enhanced sense of national identity will have many social and cultural benefits and reinforce Jersey’s remarkable community spirit, while a simultaneously enhanced international identity will protect its economic interests and lead to new opportunities. What does it mean to be Jersey in the 21st century? The complexity involved in providing any kind of answer to this question tells of an Island full of intricacy, nuance and multiplicity. Jersey is bursting with stories to tell. But none of these stories alone can tell us what it means to be Jersey. In light of all this complexity why take the time, at this moment, to investigate the different threads of what it means to be Jersey? I would, at the highest level, like to offer four main reasons: First, there is a profound and almost universally shared sense that what we have in Jersey is special. -

New Perspectives Critical Considerations for Sustainable Economic Growth

December 2020 THE ECONOMIC COUNCIL New Perspectives Critical Considerations for Sustainable Economic Growth A paper produced by the independent members of the Economic Council “We have gathered together a diverse group of high-calibre, experienced Islanders, whose objective is to deliver blue- sky thinking and new ideas. We all share the same vision – to ensure Jersey emerges from this pandemic in a strong economic position and are firmly focused on making the Island an even better place to work and live. “We are considering how Jersey can develop a more inclusive and diverse economy, which was one of the aspirations highlighted in the recent States Assembly debate on economic recovery. “We want to create the conditions that enable people and businesses to fulfil their potential, and improve the standard of living and wellbeing of all Islanders. We will be looking for initiatives that help to create new economic sectors or expand or renew existing sectors and improve the Island’s overall economic productivity.” Senator Lyndon Farnham Chair of the Economic Council, June 2020 Summary The independent members of the Economic Council have produced this paper “New Perspectives – Critical Considerations for Sustainable Economic Growth” with three things in mind: • To challenge the prevailing orientation in existing thinking and planning, which is predominantly focused on the short term. Surely, short-term decisions are more likely to take us in the right direction if we know what the long-term direction is? This paper encourages that greater consideration be given to trends that are already shaping the world and us locally so that actions taken today will enable Jersey to have a prosperous, vibrant and diverse economy from which the next generation can benefit and an inclusive society which they can nurture; • To stimulate a fresh discussion on the Government’s vision for Jersey’s economy and to recalibrate the levels of ambition we have in the Island. -

9650 Organisations in Receipt of States Grants

16 1240/5(9650) WRITTEN QUESTION TO THE MINISTER FOR TREASURY AND RESOURCES BY DEPUTY S.Y. MÉZEC OF ST. HELIER ANSWER TO BE TABLED ON TUESDAY 11TH OCTOBER 2016 Question Will the Minister provide a list of those organisations which previously regularly received a States grant and which have either had that grant reduced or cut entirely since the Minister took office? Answer Grants to organisations are at the discretion of each department based on an evaluation of whether they support the objectives of the Department and the overall Strategic Objectives of the States of Jersey. Due to the discretionary nature of grant funding, the level of funding and recipients of grants vary between years. In some cases, there will be continuity in the organisations receiving grant funding but the reason for the grant may change to support different objectives. Equally, different organisations may be in receipt of grant funding in different years to achieve the same objective. For that reason, it is important to consider the wider allocation of grants and their targeted nature in response to this question. All grant allocations are disclosed in the States of Jersey Financial Report and Accounts (Accounts) and the corresponding Annex. Any significant individual grant, now defined as £75,000 and over, is identified in the Grants Note in the Accounts (page 154 in the 2015 Accounts). Grants below this amount are listed in the Annex in Appendix A. The Minister took office in 2014 so the analysis provided in this response focuses on changes in grants allocated between 2014 and 2015.