How Do We Make Goodness Attractive?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morrie Gelman Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959p15 No online items Morrie Gelman papers, ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Finding aid prepared by Jennie Myers, Sarah Sherman, and Norma Vega with assistance from Julie Graham, 2005-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Morrie Gelman papers, ca. PASC 292 1 1970s-ca. 1996 Title: Morrie Gelman papers Collection number: PASC 292 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 80.0 linear ft.(173 boxes and 2 flat boxes ) Date (inclusive): ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Abstract: Morrie Gelman worked as a reporter and editor for over 40 years for companies including the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Post, Newsday, Broadcasting (now Broadcasting & Cable) magazine, Madison Avenue, Advertising Age, Electronic Media (now TV Week), and Daily Variety. The collection consists of writings, research files, and promotional and publicity material related to Gelman's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Gelman, Morrie Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

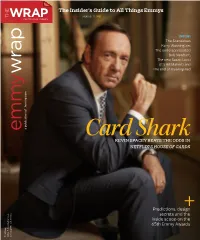

The Insider's Guide to All Things Emmys

The Insider’s Guide to All Things Emmys DOWN TO THE WIRE | AUGUST 12, 2013 COVERING HOLLYWOOD INSIDE: The Scandalous Kerry Washington, The underappreciated Bob Newhart, The new Susan Lucci (it's Bill Maher!) and The end of Breaking Bad a publication of thewrap.com of a publication Card Shark KEVIN SPACEY BEATS THE ODDS IN NETFLIX'S HOUSE OF CARDS Predictions, design+ secrets and the inside scoop on the 65th Emmy Awards TheWrap 2855 S. Barrington Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90064 CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL OUR 110 NOMINATIONS! 2013 PRIMETIME EMMY ® N O M I N E E S ! BEHIND THE CANDELABRA PHIL SPECTOR GAME OF THRONES® BOARDWALK EMPIRE® GIRLSSM REAL TIME WITH MEA MAXIMA CULPA: CROSSFIRE HURRICANE Jerry Weintraub Productions in association with Levinson/Fontana Productions in association with Bighead, Littlehead, Television 360, Startling Leverage, Closest to the Hole Productions, Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner BILL MAHER SILENCE IN THE Tremolo Productions, Milkwood Films, Eagle ® ® HBO Films HBO Films Television and Generator Productions in association Sikelia Productions and Cold Front Productions Productions in association with HBO Entertainment Bill Maher Productions and Brad Grey Television HOUSE OF GOD Rock Entertainment and the Rolling Stones in ® with HBO Entertainment in association with HBO Entertainment ® association with HBO Documentary Films OUTSTANDING MINISERIES OR MOVIE OUTSTANDING MINISERIES OR MOVIE OUTSTANDING COMEDY SERIES in association with HBO Entertainment HBO Documentary Films in association with Jerry Weintraub, Executive Producer; Barry Levinson, David Mamet, Executive Producers; OUTSTANDING DRAMA SERIES SUPPORTING ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Judd Apatow, Jenni Konner, Lena Dunham, OUTSTANDING VARIETY SERIES Jigsaw Productions, Wider Film Projects and OUTSTANDING DOCUMENTARY OR NONFICTION Gregory Jacobs, Susan Ekins, Michael Polaire, Michael Hausman, Produced by David Benio , D.B. -

5337 Programminglineup.R16

Movies HBO Plus (East & West). A perfect complementary choice to what’s on HBO. Scheduled for the broadest appeal, this channel doubles your HBO entertainment options. American Movie Classics is the premiere 24-hour movie network featuring award-winning original productions about the world of American film. With one of the finest, most comprehensive libraries of classic films and a diverse blend of original series and documentaries, AMC offers in-depth information on timeless and contemporary HBO Signature. Discriminating viewers will enjoy HBO’s critically acclaimed, Hollywood classics. award-winning original movies, series and documentaries, plus theatrical films. Cinemax® (East & West). With over 1,600 different movies a year, Cinemax gives viewers the widest variety of movies from its vast inventory with a different movie every night at The Independent Film Channel (IFC). The first network entirely dedicated to capturing and 8pm ET all year long! presenting the irreverent style of independent film, uncut and commercial-free, 24 hours a day. IFC presents the most extensive independent film collection on television like “Trainspotting,” “In the Company of Men,” and “Secrets and Lies,” combined with original series, exclusive ™ live events like the Independent Spirit Awards and the Cannes Film Festival and enhanced new MoreMAX. Doubles your Cinemax film choices with popular, hard-to-find movies. Features media programming. Featured indie celebs include Spike Lee, John Waters and Lili Taylor. daily classics and special premieres of foreign and independent films. The New Encore (East & West). The ultimate, commercial-free movie channel destination The Movie Channel (East & West). For people who just want to have movies, The Movie because it now delivers a great movie every night. -

Women's History Month 2021 Slideshow

Dolly Parton (1946 – ) Singer, Songwriter ● Composed over 3,000 songs with more than 25 reaching #1 on the Billboard country music charts. ● Starred in several films as Steel magnolias, Unlikely Angel, and A Smoky Mountain Christmas. ● Supported several charitable efforts, mainly in literacy through her Dollywood Foundation. ● Founded the Imagination Library, a program that mails one book per month to an enrolled child from the time of birth until they reach kindergarten. ● Pledged $1 million towards research at Vanderbilt University and encouraged others to make donations as well. Soo Jung Lee 이수정 (1964 – ) Forensic Psychologist, Professor ● South Korean Forensic Psychologist and part of the country's first generation of criminal profilers. ● Professor of Forensic Psychology at Kyonggi University in Seoul. ● Worked numerous high-profile murder cases and believes stalking leads to more serious crimes, in response she helped introduced an anti-stalking bill now passed in South Korea. ● Former member of the Supreme Court's Sentencing Commission, the Supreme Prosecutors' Office's sexual violence taskforce and the National Police Agency's reform committee. Stacy Abrams (1973 – ) American politician, lawyer, and author ● Served in the Georgia House of Representatives from 2007 to 2017 and served as Minority Leader from 2011 to 2017. ● First black woman to be a major-party nominee for Governor. The controversial election brought concerns of voter suppression to the forefront of politics and became Abrams mission. ● Launched the Fair Fight 2020 initiative to make sure voters aren't illegally silenced or disenfranchised in upcoming elections, focused on protecting people of color, the poor, LGBTQ folks and seniors from the tricks of the imbalanced status quo. -

Congressional Record—Senate S3204

S3204 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 5, 2003 management intern for the Committee lier today by Senators SANTORUM and ers delivered are as vital now as they on Foreign Affairs Committee, be given SPECTER. were in 1960. floor privileges during the debate on The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Mr. Rogers’ accomplishments reach the Moscow Treaty. clerk will report the concurrent resolu- far beyond the boundaries of the neigh- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without tion by title. borhood. Ordained by the Pittsburgh objection, it is so ordered. The assistant legislative clerk read Presbytery in 1962, Mr. Rogers was ac- f as follows: tive in child and family advocacy on A concurrent resolution (S. Con. Res. 16) all levels. In 1972, Mr. Rogers formed CORRECTED VERSION OF S. RES. honoring the life and work of Mr. Fred Family Communications, Inc. to 71 AS PASSED ON MARCH 4, 2003 McFeely Rogers. produce educational entertainment for Whereas a 3-judge panel of the Ninth Cir- There being no objection, the Senate children and families and resources for cuit Court of Appeals has ruled in Newdow v. proceeded to consider the concurrent teachers. Mr. Rogers most recently United States Congress that the words resolution. partnered with the Western Pennsyl- ‘‘under God’’ in the Pledge of Allegiance vio- Mr. SPECTER. Mr. President, I have vania Caring Foundation to establish late the Establishment Clause when recited sought recognition to pay tribute to the Caring Place for grieving children voluntarily by students in public schools; Mr. Fred Rogers, the beloved host of in an effort to make sure that children Whereas the Ninth Circuit has voted not to who experienced a loss did not feel so have the full court, en banc, reconsider the the Public Broadcasting Service, PBS decision of the panel in Newdow; children’s television program, Mister alone. -

Mister Rogers Supplementary Article Week 1 Chris and I Walked Down

Mister Rogers Supplementary Article Week 1 Chris and I walked down Hollywood Boulevard, scanning names on the sidewalk starts. Tom Cruise. Jack Nicholson. Johnny Cash. Meryl Streep. Leonardo DiCaprio, ABBA. Julia Roberts. Star after star, honoring the careers of film, TV, and music celebrities. And then I spotted the star I’d been searching for and posed for a picture beside it. Fred Rogers. My hero. Today the legacy of Fred Rogers lives on through the animated children’s program Daniel Tiger, which I enjoy watching with my grandson Preston. But when I was a child, Fred Rogers appeared on the program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, which aired daily on public television. If you are old enough to remember the program, you most likely recall how each episode began and can probably sing the opening tune. A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD Piano music begins, and Fred Rogers walks through the door with a smile and a wave, singing the theme song, “It’s a beautiful Day in the neighborhood”. His solo continues as he descends a short flight of stair to the closet, where he exchanges his suit coat for a zip-up sweater. Then he sits on a bench, removes his dress shoes, and laces up his sneakers. With the wardrobe change complete, he finishes the opening number with the invitation, “won’t you be, won’t you be, please won’t you be my neighbor?” This is how Fred McFeely Rogers opened his program for thirty-three years. Between 1968 and 2001, he embraced the redundancy of walking through the door and singing the same opening number while swapping out his dress coat and shoes for more casual attire. -

Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project

Los Angeles Unified School District Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Los Angeles Unified School District Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Written and Edited by Bob and Sandy Collins All publication, duplication and distribution rights are donated to the Los Angeles Unified School District by the authors First Edition August 2016 Published in the United States i Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project Founding Committee and Contributors Sincere appreciation is extended to Ray Cortines, former LAUSD Superintendent of Schools, Michelle King, LAUSD Superintendent, and Nicole Elam, Chief of Staff for their ongoing support of this project. Appreciation is extended to the following members of the Founding Committee of the Alumni History and Hall of Fame Project for their expertise, insight and support. Jacob Aguilar, Roosevelt High School, Alumni Association Bob Collins, Chief Instructional Officer, Secondary, LAUSD (Retired) Sandy Collins, Principal, Columbus Middle School (Retired) Art Duardo, Principal, El Sereno Middle School (Retired) Nicole Elam, Chief of Staff Grant Francis, Venice High School (Retired) Shannon Haber, Director of Communication and Media Relations, LAUSD Bud Jacobs, Director, LAUSD High Schools and Principal, Venice High School (Retired) Michelle King, Superintendent Joyce Kleifeld, Los Angeles High School, Alumni Association, Harrison Trust Cynthia Lim, LAUSD, Director of Assessment Robin Lithgow, Theater Arts Advisor, LAUSD (Retired) Ellen Morgan, Public Information Officer Kenn Phillips, Business Community Carl J. Piper, LAUSD Legal Department Rory Pullens, Executive Director, LAUSD Arts Education Branch Belinda Stith, LAUSD Legal Department Tony White, Visual and Performing Arts Coordinator, LAUSD Beyond the Bell Branch Appreciation is also extended to the following schools, principals, assistant principals, staffs and alumni organizations for their support and contributions to this project. -

No. 2, June 1998

Vol. 26:2 ISSN 0160-8460 June 1998 First Lady Announces $1 Million Award to Five Founding Fathers Projects First Lady Hilary Rodham Clinton has announced that a grant of $1 million has been contributed by television producer Norman Lear for the editing and publishing of five Founding Fathers projects—the Papers of Thomas Jefferson, the Adams Family Papers, the Papers of James Madison, the Papers of George Washington, and the Papers of Benjamin Franklin. On July 9, 1998, with the south portico of the White House as a backdrop, Mrs. Clinton unveiled the logo for the White House Millennium Council and its “Save America’s Treasures” program as she launched a tour of several historic locations. The following day, standing in front of Montpelier, James Madison’s home in Orange County, Virginia, she said that the gift from Mr. Lear and his family “will help ensure that the ideas and ideals which built our nation survive forever.” These five projects receive major Federal support from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Mrs. Clinton said that the NEH, in administering the grant, “will work along with the National Archives to collect and safeguard the writings of those Americans from whom we continue to look for inspiration.” Mr. Lear has produced some of the most critically acclaimed serials in the history of television, including All in the Family and The Jeffersons. The Television Hall of Fame honored him as one of its very first inductees. Mr. Lear has also been a staunch advocate of First Amendment rights; he was founder of People for the American Way. -

Black Theatre Insights

Black History Month & Theatre Insights 1 Purpose: As a way to acknowledge, highlight, celebrate, uplift, and honor the past and present Black theatre artists who have contributed so much to our theatre canon, I thought it would be worthwhile in creating daily emails to be sent throughout the month of February which consisted of a fact, artist, and play of the day. These daily emails culminated in a Black History Month Play Exchange on February 27th, as an event and space for folks to come together to give and share presentations on their chosen play from the list of plays sent out over the course of the month. It is my hope that we take the spirit of widening our knowledge of our theatre history and work towards making known the contributions of all the marginalized groups who have been critical in cementing the foundation of the theatre we all enjoy today. Acknowledgments: Thank you to Adarian Sneed for helping me create this idea during those late zoom calls on those cold, lonely winter break nights where we just laughed, existed, and bolstered one another’s creative thoughts. Thank you to the Anthony Aston Players for allowing me the space to use your listserv as a way to spread this knowledge and history. Thank you to Leslie Spencer and Sierra Browning for helping contribute some of the artist spotlights. I am forever grateful to all the kind emails I received from folks in support of this project as it truly made these emails an important part of my daily routine. -

Alan Alda to Be Honored with 2018 SAG Life Achievement Award

Alan Alda to be Honored with 2018 SAG Life Achievement Award 55th Annual Accolade to be Presented During the 25th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® Simulcast Live on TNT and TBS on Sunday, January 27, 2019 Award-winning actor, writer, director, producer, polymath and advocate for science communication Alan Alda has been named the 55th recipient of SAG-AFTRA's highest tribute: the SAG Life Achievement Award for career achievement and humanitarian accomplishment. Alda will be presented the performers union's top accolade at the 25th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards®, which will be simulcast live on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2019, at 8 p.m. (ET)/ 5 p.m. (PT). Given annually to an actor who fosters the "finest ideals of the acting profession," the SAG Life Achievement Award will join Alda’s exceptional catalog of pre-eminent industry and public honors. His career has earned him induction into the Television Hall of Fame, an Oscar® nomination, six Emmys® (plus an International Emmy® Special Founder's Award and 29 additional Emmy® nominations), four SAG Award® nominations, six Golden Globes®, four DGA Awards (including the D. W. Griffith Award), the WGA’s Valentine Davis Award, three Tony Award® nominations and more. In fact, he is one of only six people to receive Oscar®, Tony® and Emmy® nominations in the same year. This abbreviated list doesn’t even mention his numerous honors from the scientific community, including most recently the National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal. “It is an honor and privilege to announce that our SAG Life Achievement Award will be presented to the fabulous Alan Alda,” said SAG-AFTRA President Gabrielle Carteris. -

Commencement Speaker: Jim Lehrer and the Honorary Degree Recipients Total Undergraduate Charges

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday, March 26, 2002 Volume 48 Number 27 www.upenn.edu/almanac/ Commencement Speaker: Jim Lehrer and the Honorary Degree Recipients Joan Ganz Cooney Eric Hobsbawm Irwin Jacobs Jim Lehrer Richard E. Smalley Award-winning television journalist Jim medium for children. Dr. Richard Smalley, whose research has led Lehrer, will deliver the Commencement address Dr. Eric Hobsbawm, an influential historian to the discovery of a third elemental form of at Penn’s 246th Commencement on Monday, whose works have been translated into dozens of carbon and who pioneered supersonic beam la- May 13 at Franklin Field. languages and who has lectured in more than 30 ser spectroscopy which has become one of the Mr. Lehrer will receive an honorary degree countries. most powerful techniques in chemical physics. as will four others. Dr. Irwin Jacobs, an innovative engineer and *** Mrs. Joan Ganz Cooney, co-founder of the co-founder, chairman and CEO of Qualcomm, See page 8 for more on the honorary degree Children’s Television Workshop (now Sesame whose pioneering work led to the commercial- recipients. For commencement information see Workshop), a television producer and media ization of digital wireless communication tech- the website, www.upenn.edu/commencement or executive who pioneered educational uses of the nology. call the hotline, (215) 573-GRAD. Total Undergraduate Charges: 4.6 Percent Increase for 2002-2003 Total undergraduate charges for tuition, fees, duce the debt burden on our students by increas- graduate residence halls, including the completion room and board at Penn will increase 4.6 per- ing the number of grants offered to students and this summer of a four-year $75 million renovation cent for the 2002-2003 academic year from reducing loans,” President Rodin said. -

Media Persons of the Year Awards Gala St. Louis Press Club's

ST. LOUIS PRESS CLUB’S MEDIA PERSONS OF THE YEAR AWARDS GALA Wednesday, February 21, 2018 5:30 p.m. Reception, 6:15 p.m. Dinner and Awards Program Edward Jones Corp. North Campus 130 Edward Jones Blvd., Maryland Heights, MO 63043 2018 MEDIA PERSONS OF THE YEAR AWARDEES PRINT TELEVISION TELEVISION Eric Mink Betsey Bruce Frank Cusumano LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT RADIO POSTHUMOUSly Jim Lehrer KSHE 95 John Auble ST. LOUIS PRESS CLUB’S SPONSORSHIPS & TICKETS $25,000 PRESENTING SPONSOR $2,500 VIP SPONSOR - Honorary Gala chairpersons - One table of 10 for Media Persons of the Year Gala and - Remarks at event Dinner - Three prime-location tables of 10 at Media Persons of the - Inclusion in invitations, printed program, on-site signage Year Gala and Dinner and logo video at Gala - Invitation to photography session with honorees prior to the start of Gala -Inclusion in all media releases/announcements and $1,500 TABLE SPONSOR printed materials for Media Person of the Year Gala, - One table for 10 for Media Persons of the Year Gala and including invitations, programs, on-site signage, Dinner logo video and emcee mentions at Gala - Inclusion in program and logo video at Gala -$1,000 Media Scholarship in sponsor’s name $150 INDIVIDUAL TICKET $15,000 PROGRAM AND AWARD SPONSOR - Introduction at event - Two prime-location tables of 10 for Media Persons of the $125 PRESS CLUB MEMBER TICKET Year Gala and Dinner EW EMBER ISCOUNT Join St. Louis Press Club - Invitation to photography session with honorees prior to N M D : and receive a $25 discount on each ticket for yourself and one the start of Gala guest -Inclusion in all media releases/announcements and printed materials for Media Person of the Year Gala, Make paid reservations by credit card at including invitations, programs, on-site signage, www.stlpressclub.org or by mailing a check to logo video and emcee mentions at Gala St.