South Africa, Apartheid, Liberalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Restoration of Tulbagh As Cultural Signifier

BETWEEN MEMORY AND HISTORY: THE RESTORATION OF TULBAGH AS CULTURAL SIGNIFIER Town Cape of A 60-creditUniversity dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in the Conservation of the Built Environment. Jayson Augustyn-Clark (CLRJAS001) University of Cape Town / June 2017 Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment: School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ‘A measure of civilization’ Let us always remember that our historical buildings are not only big tourist attractions… more than just tradition…these buildings are a visible, tangible history. These buildings are an important indication of our level of civilisation and a convincing proof for a judgmental critical world - that for more than 300 years a structured and proper Western civilisation has flourished and exist here at the southern point of Africa. The visible tracks of our cultural heritage are our historic buildings…they are undoubtedly the deeds to the land we love and which God in his mercy gave to us. 1 2 Fig.1. Front cover – The reconstructed splendour of Church Street boasts seven gabled houses in a row along its western side. The author’s house (House 24, Tulbagh Country Guest House) is behind the tree (photo by Norman Collins). -

Constitutional Authority and Its Limitations: the Politics of Sexuality in South Africa

South Africa Constitutional Authority and its Limitations: The Politics of Sexuality in South Africa Belinda Beresford Helen Schneider Robert Sember Vagner Almeida “While the newly enfranchised have much to gain by supporting their government, they also have much to lose.” Adebe Zegeye (2001) A history of the future: Constitutional rights South Africa’s Constitutional Court is housed in an architecturally innovative complex on Constitution Hill, a 100-acre site in central Johannesburg. The site is adjacent to Hillbrow, a neighborhood of high-rise apartment buildings into which are crowded thousands of mi- grants from across the country and the continent. This is one of the country’s most densely populated, cosmopolitan and severely blighted urban areas. From its position atop Constitu- tion Hill, the Court offers views of Hillbrow’s high-rises and the distant northern suburbs where the established white elite and increasing numbers of newly affluent non-white South Africans live. Thus, while the light-filled, colorful and contemporary Constitutional Court buildings reflect the progressive and optimistic vision of post-apartheid South Africa the lo- cation is a reminder of the deeply entrenched inequalities that continue to define the rights of the majority of people in the country and the continent. CONSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY AND ITS LIMITATIONS: THE POLITICS OF SEXUALITY IN SOUTH AFRICA 197 From the late 1800s to 1983 Constitution Hill was the location of Johannesburg’s central prison, the remains of which now lie in the shadow of the new court buildings. Former prison buildings include a fort built by the Boers (descendents of Dutch settlers) in the late 1800s to defend themselves against the thousands of men and women who arrived following the discovery of the area’s expansive gold deposits. -

The Quest for Liberation in South Africa: Contending Visions and Civil Strife, Diaspora and Transition to an Emerging Democracy

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 30, Nr 2, 2000. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Quest for Liberation in South Africa: Contending Visions and Civil Strife, Diaspora and Transition to an Emerging Democracy Ian Liebenberg Introduction: Purpose of this contribution To write an inclusive history of liberation and transition to democracy in South Africa is almost impossible. To do so in the course of one paper is even more demanding, if not daunting. Not only does "the liberation struggle" in South Africa in its broadest sense span more than a century. It also saw the coming and going of movements, the merging and evolving of others and a series of principled and/or pragmatic pacts in the process. The author is attempting here to provide a rather descriptive (and as far as possible, chronological) look at and rudimentary outline to the main organisational levels of liberation in South Africa since roughly the 1870' s. I will draw on my own 2 work in the field lover the past fifteen years as well as other sources • A wide variety of sources and personal experiences inform this contribution, even if they are not mentioned here. Also needless to say, one's own subjectivities may arise - even if an attempt is made towards intersubjecti vity. This article is an attempt to outline and describe the organisations (and where applicable personalities) in an inclusive and descriptive research approach in See Liebenberg (1990), ldeologie in Konjlik, Emmerentia: Taurus Uitgewers; Liebenberg & Van der Merwe (1991), Die Wordingsgeskiedenis van Apartheid, Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis, vol 16(2): 1-24; Liebenberg (1994), Resistance by the SANNC and the ANC, 1912 - 1960, in Liebenberg et al (Eds.) The Long March: The Story of the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa. -

Remgro at a Glance

OVERVIEW I II CONTENTS 2 14 Group profi le Remgro's values 4 16 Remgro's unlisted investments Directorate and ownership structure Originally established in the 1940s by 6 20 A strong family legacy Tomorrow matters the late Dr Anton Rupert, Remgro aims to be the trusted investment company 8 23 Investment strategy Doing business ethically of choice that consistently creates 10 24 sustainable stakeholder value. Remgro's approach to capital allocation Consolidated results at year-end 12 26 Remgro’s profi t at holding company level Investment portfolio analysis 1 GROUP PROFILE DIVERSIFIED CONSUMER FINANCIAL PORTFOLIO SOCIAL IMPACT HEALTHCARE INFRASTRUCTURE INDUSTRIAL INVESTMENT MEDIA Our interests PRODUCTS SERVICES INVESTMENTS INVESTMENTS VEHICLES consist mainly of investments (2) in the following industries 44.6% 77.1% 30.6% 54.7% 50.0% 36.3% 32.3% 4.0% 50.0% (3) (1) 31.8% 44.1% 23.3% 24.9% 28.1% 0.1% 100% (3) 100% 22.8% 100% 44.1% 100% Equity accounted investment Subsidiary Investment at fair value through other comprehensive income 30.0% 37.7% 100% Listed entity Number of Remgro nominated director/s; alternates excluded (3) infrastructure fund (1) Voting rights in Distell equal 56.4%. (2) Voting rights in Blue Bulls equal 36.7%. 33% 16.2% (3) Limited Partners in Pembani Remgro, Milestone Capital and Prescient – therefore limited (or no) voting rights. 2 3 REMGRO’S INDUSTRIAL INFRASTRUCTURE Why does UNLISTED PGSI holds an interest in PG Group Remgro invest Holdings, South Africa’s leading infrastructure fund INVESTMENTS integrated fl at glass business. in certain CIVH’s key operating PRIF is a fund Air Products produces oxygen, companies are Dark focused on private nitrogen, argon, hydrogen and carbon sectors? CONSUMER PRODUCTS Fibre Africa and Vumatel, sector investment in dioxide for sale to major industrial which construct and own infrastructure across users. -

True Confessions, End Papers and the Dakar Conference

Hermann Giliomee True Confessions, End Papers and Hermann Giliomee was Professor of the Dakar conference: A review of Political Studies at the University of Cape Town and is presently Professor the political arguments Extraordinary at the History Department, University of Stellenbosch. E-mail: [email protected] True Confessions, End Papers and the Dakar conference: A review of the political arguments As a social critic Breyten Breytenbach published two books of political commentary and political analysis during the mid-1980s without the opportunity of engaging with commentators at home. While True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist is part autobiography and part searing comment on prison life, End Papers is a more detached dissection of the major political and cultural issues confronting South Africa. Breytenbach was now one of the respected international voices on the political crisis in South Africa. The violent break-up of apartheid had changed Breytenbach’s social criticism. In the place of the earlier rejection and denunciation had come a willingness to engage and reason with his audience. The Dakar conference of 1987, which Breytenbach co-organised, offered an ideal opportunity for this. The conference was given wide publicity and was seen by some as the catalyst that broke the ice for the negotiations between the government and the ANC two and a half years later. Key words: Afrikaans literature, Dakar conference, National Party, African National Congress, South Africa, violence, negotiations. Introduction Shortly after being released from jail in 1982 Breyten Breytenbach published two non-fiction books, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (1984) and End Papers (1986). -

The Black Sash

THE BLACK SASH THE BLACK SASH MINUTES OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 CONTENTS: Minutes Appendix Appendix 4. Appendix A - Register B - Resolutions, Statements and Proposals C - Miscellaneous issued by the National Executive 5 Long Street Mowbray 7700 MINUTES OF THE BLACK SASH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 - GRAHAMSTOWN SESSION 1: FRIDAY 2 MARCH 1990 14:00 - 16:00 (ROSEMARY VAN WYK SMITH IN THE CHAIR) I. The National President, Mary Burton, welcomed everyone present. 1.2 The Dedication was read by Val Letcher of Albany 1.3 Rosemary van wyk Smith, a National Vice President, took the chair and called upon the conference to observe a minute's silence in memory of all those who have died in police custody and in detention. She also asked the conference to remember Moira Henderson and Netty Davidoff, who were among the first members of the Black Sash and who had both died during 1989. 1.4 Rosemary van wyk Smith welcomed everyone to Grahamstown and expressed the conference's regrets that Ann Colvin and Jillian Nicholson were unable to be present because of illness and that Audrey Coleman was unable to come. All members of conference were asked to introduce themselves and a roll call was held. (See Appendix A - Register for attendance list.) 1.5 Messages had been received from Errol Moorcroft, Jean Sinclair, Ann Burroughs and Zilla Herries-Baird. Messages of greetings were sent to Jean Sinclair, Ray and Jack Simons who would be returning to Cape Town from exile that weekend. A message of support to the family of Anton Lubowski was approved for dispatch in the light of the allegations of the Minister of Defence made under the shelter of parliamentary privilege. -

200 1. Voortrekkers Were Groups of Nineteenth- Century Afrikaners Who

Notes 1. Voortrekkers were groups of nineteenth- century Afrikaners who migrated north from the Cape colony into the South African interior to escape British rule. 2. ‘Township’ is the name given by colonial and later apartheid authorities to underdeveloped, badly resourced urban living areas, usually on the outskirts of white towns and cities, which were set aside for the black workforce. 3. See, for example, Liz Gunner on Zulu radio drama since 1941 (2000), David Coplan on township music and theatre (1985) and Isabel Hofmeyr on the long- established Afrikaans magazine Huisgenoot (1987). 4. In 1984 the NP launched what it called a ‘tricameral’ parliament, a flawed and divisive attempt at reforming the political system. After a referendum among white voters it gave limited political representation to people classi- fied as coloured and Indian, although black South Africans remained com- pletely excluded. Opposition to the system came from both the left and right and voting rates among non- whites remained extremely low, in a show of disapproval of what many viewed as puppet MPs. 5. The State of Emergency was declared in 1985 in 36 magisterial districts. It was extended across the whole country in 1986 and given an extra year to run in 1989. New measures brought in included the notorious 90- day law, in which suspects could be held without trial for 90 days, after which many were released and then re- arrested as they left the prison. 6. According to André Brink, ‘The widespread notion of “traditional Afrikaner unity” is based on a false reading of history: strife and division within Afrikanerdom has been much more in evidence than unity during the first three centuries of white South African history’ (1983, 17). -

Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa's Dominant

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 © Copyright by Safia Abukar Farole 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Eroding Dominance from Below: Opposition Party Mobilization in South Africa’s Dominant Party System by Safia Abukar Farole Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Kathleen Bawn, Chair In countries ruled by a single party for a long period of time, how does political opposition to the ruling party grow? In this dissertation, I study the growth in support for the Democratic Alliance (DA) party, which is the largest opposition party in South Africa. South Africa is a case of democratic dominant party rule, a party system in which fair but uncompetitive elections are held. I argue that opposition party growth in dominant party systems is explained by the strategies that opposition parties adopt in local government and the factors that shape political competition in local politics. I argue that opposition parties can use time spent in local government to expand beyond their base by delivering services effectively and outperforming the ruling party. I also argue that performance in subnational political office helps opposition parties build a reputation for good governance, which is appealing to ruling party ii. supporters who are looking for an alternative. Finally, I argue that opposition parties use candidate nominations for local elections as a means to appeal to constituents that are vital to the ruling party’s coalition. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

Pressure on Model School to Shape Up

PRESSURE ON MODEL SCHOOL TO SHAPE-UP By Tselane Moiloa KROONSTAD – The Free State provincial government’s education theme during the weeklong celebrations to mark former president Nelson Mandela’s birthday on Wednesday, July 18, has resonated with learners at Bodibeng Secondary School who have been asked to change the path the school has taken in recent years. Located between the dusty townships of Marabastad and Seeisoville, Bodibeng was counted among the best schools in Free State and South Africa during the apartheid regime and the early 90s, after producing luminaries like the late Adelaide Tambo and former Minister of Communications Ivy Matsepe-Casaburri, Mosuioa “Terror” Lekota, MEC Butana Khompela and his soccer-coach brother Steve Khompela. The school, which was founded in 1928 under the name Bantu High, was the only school for black people during the apartheid regime which offered a joint matriculation board qualification instead of the Bantu education senior certificate, putting it on par with the regime’s best schools of the time. Until 1982, it was the only high school in Kroonstad. But the famed reputation took a knock, despite an abundance of resources. “There is obviously a lot of pressure on us to continue with the legacy and it only makes sense that we come through with our promise to do so,” Principal Itumeleng Bekeer said. Unlike many schools which complain about things like unsatisfactory teacher-learner ratios, Bekeer said this is not a concern because the 24 classes from grade eight to 12 have an average 1:24 teacher-learner ratio. However, the socio-economic circumstances in the surrounding townships impact negatively on learners, with a lot coming to school on empty stomachs. -

South Africa

<*x>&&<>Q&$>ee$>Q4><><>&&i<>4><><i^^ South Africa UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA HE political tension of the previous three years in the Union of South TAfrica (see articles on South Africa in the AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, Vols. 51, 52 and 53) broke, during the period under review, into a major constitutional crisis. A struggle began between the legislature and the judi- ciary over the "entrenched clauses" of the South Africa Act, which estab- lished the Union, and over the validity of a law passed last year by Daniel Francois Malan's Nationalist Government to restrict the franchise of "Col- ored" voters in Cape Province in contravention of these provisions. Simul- taneously, non-European (nonwhite) representative bodies started a passive resistance campaign against racially discriminatory legislation enacted by the present and previous South African governments. Resulting unsettled condi- tions in the country combined with world-wide economic trends to produce signs of economic contraction in the Union. The developing political and racial crisis brought foreign correspondents to report at first hand upon conditions in South Africa. Not all their reports were objective: some were characterized by exaggeration and distortion, and some by incorrect data. This applied particularly to charges of Nationalist anti-Semitism made in some reports. E. J. Horwitz, chairman of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies (central representative body of South Afri- can Jewry) in an interview published in Die Transvaler of May 16, 1952, specifically refuted as "devoid of all truth" allegations of such anti-Semitism, made on May 5, 1952, in the American news magazine Time. -

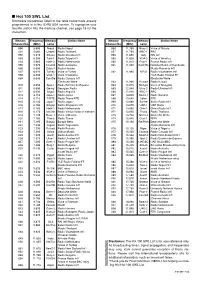

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice