Cukor, George (1899-1983) by Gary Morris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadway the BROAD Way”

MEDIA CONTACT: Fred Tracey Marketing/PR Director 760.643.5217 [email protected] Bets Malone Makes Cabaret Debut at ClubM at the Moonlight Amphitheatre on Jan. 13 with One-Woman Show “Broadway the BROAD Way” Download Art Here Vista, CA (January 4, 2018) – Moonlight Amphitheatre’s ClubM opens its 2018 series of cabaret concerts at its intimate indoor venue on Sat., Jan. 13 at 7:30 p.m. with Bets Malone: Broadway the BROAD Way. Making her cabaret debut, Malone will salute 14 of her favorite Broadway actresses who have been an influence on her during her musical theatre career. The audience will hear selections made famous by Fanny Brice, Carol Burnett, Betty Buckley, Carol Channing, Judy Holliday, Angela Lansbury, Patti LuPone, Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, Liza Minnelli, Bernadette Peters, Barbra Streisand, Elaine Stritch, and Nancy Walker. On making her cabaret debut: “The idea of putting together an original cabaret act where you’re standing on stage for ninety minutes straight has always sounded daunting to me,” Malone said. “I’ve had the idea for this particular cabaret format for a few years. I felt the time was right to challenge myself, and I couldn’t be more proud to debut this cabaret on the very stage that offered me my first musical theatre experience as a nine-year-old in the Moonlight’s very first musical Oliver! directed by Kathy Brombacher.” Malone can relate to the fact that the leading ladies she has chosen to celebrate are all attached to iconic comedic roles. “I learned at a very young age that getting laughs is golden,” she said. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

An Analysis and Evaluation of the Acting Career Of

AN ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION OF THE ACTING CAREER OF TALLULAH BANKHEAD APPROVED: Major Professor m Minor Professor Directororf? DepartmenDepa t of Speech and Drama Dean of the Graduate School AN ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION OF THE ACTING CAREER OF TALLULAH BANKHEAD THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Jan Buttram Denton, Texas January, 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. THE BEGINNING OF SUCCESS 1 II. ACTING, ACTORS AND THE THEATRE 15 III. THE ROLES SHE USUALLY SHOULD NOT HAVE ACCEPTED • 37 IV. SIX WITH MERIT 76 V. IN SUMMARY OF TALLULAH 103 APPENDIX 114 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 129 CHAPTER I THE BEGINNING OF SUCCESS Tallulah Bankhead's family tree was filled with ancestors who had served their country; but none, with the exception of Tallulah, had served in the theatre. Both her grandfather and her mother's grandfather were wealthy Alabamians. The common belief was that Tallulah received much of her acting talent from her father, but accounts of her mother1s younger days show proof that both of her parents were vivacious and talented. A stranger once told Tallulah, "Your mother was the most beautiful thing that ever lived. Many people have said you get your acting talent from your father, but I disagree. I was at school with Ada Eugenia and I knew Will well. Did you know that she could faint on 1 cue?11 Tallulahfs mother possessed grace and beauty and was quite flamboyant. She loved beautiful clothes and enjoyed creating a ruckus in her own Southern world.* Indeed, Tallulah inherited her mother's joy in turning social taboos upside down. -

The Honorable Mentions Movies- LIST 1

The Honorable mentions Movies- LIST 1: 1. A Dog's Life by Charlie Chaplin (1918) 2. Gone with the Wind Victor Fleming, George Cukor, Sam Wood (1940) 3. Sunset Boulevard by Billy Wilder (1950) 4. On the Waterfront by Elia Kazan (1954) 5. Through the Glass Darkly by Ingmar Bergman (1961) 6. La Notte by Michelangelo Antonioni (1961) 7. An Autumn Afternoon by Yasujirō Ozu (1962) 8. From Russia with Love by Terence Young (1963) 9. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors by Sergei Parajanov (1965) 10. Stolen Kisses by François Truffaut (1968) 11. The Godfather Part II by Francis Ford Coppola (1974) 12. The Mirror by Andrei Tarkovsky (1975) 13. 1900 by Bernardo Bertolucci (1976) 14. Sophie's Choice by Alan J. Pakula (1982) 15. Nostalghia by Andrei Tarkovsky (1983) 16. Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders (1984) 17. The Color Purple by Steven Spielberg (1985) 18. The Last Emperor by Bernardo Bertolucci (1987) 19. Where Is the Friend's Home? by Abbas Kiarostami (1987) 20. My Neighbor Totoro by Hayao Miyazaki (1988) 21. The Sheltering Sky by Bernardo Bertolucci (1990) 22. The Decalogue by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1990) 23. The Silence of the Lambs by Jonathan Demme (1991) 24. Three Colors: Red by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1994) 25. Legends of the Fall by Edward Zwick (1994) 26. The English Patient by Anthony Minghella (1996) 27. Lost highway by David Lynch (1997) 28. Life Is Beautiful by Roberto Benigni (1997) 29. Magnolia by Paul Thomas Anderson (1999) 30. Malèna by Giuseppe Tornatore (2000) 31. Gladiator by Ridley Scott (2000) 32. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring by Peter Jackson (2001) 33. -

The Glorious Career of Comedienne Judy Holliday Is Celebrated in a Complete Nine-Film Retrospective

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1996 Contact: Graham Leggat 212/708-9752 THE GLORIOUS CAREER OF COMEDIENNE JUDY HOLLIDAY IS CELEBRATED IN A COMPLETE NINE-FILM RETROSPECTIVE Series Premieres New Prints of Born Yesterday and The Marrying Kind Restored by The Department of Film and Video and Sony Pictures Born Yesterday: The Films of Judy Holliday December 27,1996-January 4,1997 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Special Premiere Screening of the Restored Print of Born Yesterday Introduced in Person by Betty Comden on Monday, December 9,1996, at 6:00 p.m. Judy Holliday approached screen acting with extraordinary intelligence and intuition, debuting in the World War II film Winged Victory (1944) and giving outstanding comic performances in eight more films from 1949 to 1960, when her career was cut short by illness. Beginning December 27, 1996, The Museum of Modern Art presents Born Yesterday: The Films of Judy Holliday, a complete retrospective of Holliday's short but exhilarating career. Holliday's experience working with director George Cukor on Winged Victory led to a collaboration with Cukor, Garson Kanin, and Kanin's wife Ruth Gordon, resulting in Adam's Rib (1949), Born Yesterday (1950), The Marrying Kind (1952), and // Should Happen To You (1952). She went on to make Phffft (1954), The Solid Gold Cadillac (1956), Full of Life (1956), and, for director Vincente Minnelli, Bells Are Ringing (1960). -more- 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019 Tel: 212-708-9400 Fax: 212-708-9889 2 The Department of Film and Video and Sony Pictures Entertainment are restoring the six films that Holliday made at Columbia Pictures from 1950 to 1956. -

Selznick Memos Concerning Gone with the Wind-A Selection

Selznick memos concerning Gone with the Wind-a selection Memo from David O. Se/znick, selected and edited by Rudy Behlmer (New York: Viking, 1972) 144 :: MEMO FROM DAVID O. SELZNICK Gone With the Wind :: 145 To: Mr. Wm. Wright January 5, 1937 atmosphere, or because of the splendid performances, or because of cc: Mr. M. C. Cooper George's masterful job of direction; but also because such cuts as we . Even more extensive than the second-unit work on Zenda is the made in individual scenes defied discernment. work on Gone With the Wind, which requires a man really capable, We have an even greater problem in Gone With the Wind, because literate, and with a respect for research to re-create, in combination it is so fresh in people's minds. In the case of ninety-nine people out with Cukor, the evacuation of Atlanta and other episodes of the war of a hundred who read and saw Copperfield, there were many years and Reconstruction Period. I have even thought about [silent-fllm between the reading and the seeing. In the case of Gone With the director1 D. W. Griffith for this job. Wind there will be only a matter of months, and people seem to be simply passionate about the details of the book. All ofthis is a prologue to saying that I urge you very strongly indeed Mr. Sidney Howard January 6, 1937 against making minor changes, a few of which you have indicated in 157 East 8znd Street your adaptation, and which I will note fully. -

Understanding Steven Spielberg

Understanding Steven Spielberg Understanding Steven Spielberg By Beatriz Peña-Acuña Understanding Steven Spielberg Series: New Horizon By Beatriz Peña-Acuña This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Beatriz Peña-Acuña Cover image: Nerea Hernandez Martinez All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0818-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0818-7 This text is dedicated to Steven Spielberg, who has given me so much enjoyment and made me experience so many emotions, and because he makes me believe in human beings. I also dedicate this book to my ancestors from my mother’s side, who for centuries were able to move from Spain to Mexico and loved both countries in their hearts. This lesson remains for future generations. My father, of Spanish Sephardic origin, helped me so much, encouraging me in every intellectual pursuit. I hope that contemporary researchers share their knowledge and open their minds and hearts, valuing what other researchers do whatever their language or nation, as some academics have done for me. Love and wisdom have no language, nationality, or gender. CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 Spielberg’s Personal Context and Executive Production Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 19 Spielberg’s Behaviour in the Process of Film Production 2.1. -

Hollywood's Image of the Working Woman

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1995 Hollywood's image of the working woman Jody Elizabeth Dawson University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Dawson, Jody Elizabeth, "Hollywood's image of the working woman" (1995). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 516. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/f1nc-wwio This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

032343 Born Yesterday Insert.Indd

among others. He is a Senior Fight Director with OUR SPONSORS ABOUT CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY Dueling Arts International and a founding member of Dueling Arts San Francisco. He is currently Chevron (Season Sponsor) has been the Center REP is the resident, professional theatre CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY teaching combat related classes at Berkeley Rep leading corporate sponsor of Center REP and company of the Lesher Center for the Arts. Our season Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director School of Theatre. the Lesher Center for the Arts for the past nine consists of six productions a year – a variety of musicals, LYNNE SOFFER (Dialect Coach) has coached years. In fact, Chevron has been a partner of dramas and comedies, both classic and contemporary, over 250 theater productions at A.C.T., Berkeley the LCA since the beginning, providing funding that continually strive to reach new levels of artistic presents Rep, Magic Theatre, Marin Theater Company, for capital improvements, event sponsorships excellence and professional standards. Theatreworks, Cal Shakes, San Jose Rep and SF and more. Chevron generously supports every Our mission is to celebrate the power of the human Opera among others including ten for Center REP. Center REP show throughout the season, and imagination by producing emotionally engaging, Her regional credits include the Old Globe, Dallas is the primary sponsor for events including Theater Center, Arizona Theatre Company, the intellectually involving, and visually astonishing Arena Stage, Seattle Rep and the world premier the Chevron Family Theatre Festival in July. live theatre, and through Outreach and Education of The Laramie Project at the Denver Center. -

Honey, You Know I Can't Hear You When You Aren

Networking Knowledge Honey, You Know I Can’t Hear You (Jun. 2017) Honey, You Know I Can’t Hear You When You Aren’t in the Room: Key Female Filmmakers Prove the Importance of Having a Female in the Writing Room DR ROSANNE WELCH, Stephens College MFA in Screenwriting; California State University, Fullerton ABSTRACT The need for more diversity in Hollywood films and television is currently being debated by scholars and content makers alike, but where is the proof that more diverse writers will create more diverse material? Since all forms of art are subjective, there is no perfect way to prove the importance of having female writers in the room except through samples of qualitative case studies of various female writers across the history of film. By studying the writing of several female screenwriters – personal correspondence, interviews and their writing for the screen – this paper will begin to prove that having a female voice in the room has made a difference in several prominent films. It will further hypothesise that greater representation can only create greater opportunity for more female stories and voices to be heard. Research for my PhD dissertation ‘Married: With Screenplay’ involved the work of several prominent female screenwriters across the first century of filmmaking, including Anita Loos, Dorothy Parker, Frances Goodrich and Joan Didion. In all of their memoirs and other writings about working on screenplays, each mentioned the importance of (often) being the lone woman in the room during pitches and during the development of a screenplay. Goodrich summarised all their experiences concisely when she wrote, ‘I’m always the only woman working on the picture and I hold the fate of the women [characters] in my hand… I’ll fight for what the gal will or will not do, and I can be completely unfeminine about it.’ Also, the rise of female directors, such as Barbra Streisand or female production executives, such as Kathleen Kennedy, prove that one of the greatest assets to having a female voice in the room is the ability to invite other women inside. -

{DOWNLOAD} the More the Merrier Ebook

THE MORE THE MERRIER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anne Fine | 160 pages | 28 Nov 2006 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780440867333 | English | London, United Kingdom The More the Merrier PDF Book User Ratings. It doesn't sound that hard to think up but the events that lead toward the end result where the parts that are hard to think up when writing. Washington officials objected to the title and plot elements that suggested "frivolity on the part of Washington workers". Release Dates. Edit page. Emily in Paris. Joe asks Connie to go to dinner with him. User Reviews. Dingle calls Joe to meet him for dinner. Apr 28, Or that intimate scene where McCrea gives a carrying case to Jean Arthur. External Sites. Their acting is so subtly romantic in that scene. Two's a Crowd screenplay by Garson Kanin uncredited [1]. Save Word. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. The Good Lord Bird. It's shocking how believably he pulls off the scene in which McCrea and Arthur wander around the apartment without bumping into each other. Quotes [ first lines ] Narrator : Our vagabond camera takes us to beautiful Washington, D. Alternate Versions. If you like classic comedies then this must be on your watch list. Share the more the merrier Post the Definition of the more the merrier to Facebook Share the Definition of the more the merrier on Twitter. The More the Merrier Writer New York: Limelight Editions. September 16, Rating: 4. Tools to create your own word lists and quizzes. Variety Staff. You may later unsubscribe. -

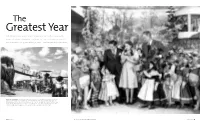

Greatest Year with 476 Films Released, and Many of Them Classics, 1939 Is Often Considered the Pinnacle of Hollywood Filmmaking

The Greatest Year With 476 films released, and many of them classics, 1939 is often considered the pinnacle of Hollywood filmmaking. To celebrate that year’s 75th anniversary, we look back at directors creating some of the high points—from Mounument Valley to Kansas. OVER THE RAINBOW: (opposite) Victor Fleming (holding Toto), Judy Garland and producer Mervyn LeRoy on The Wizard of Oz Munchkinland set on the MGM lot. Fleming was held in high regard by the munchkins because he never raised his voice to them; (above) Annie the elephant shakes a rope bridge as Cary Grant and Sam Jaffe try to cross in George Stevens’ Gunga Din. Filmed in Lone Pine, Calif., the bridge was just eight feet off the ground; a matte painting created the chasm. 54 dga quarterly photos: (Left) AMpAs; (Right) WARneR BRos./eveRett dga quarterly 55 ON THEIR OWN: George Cukor’s reputation as a “woman’s director” was promoted SWEPT AWAY: Victor Fleming (bottom center) directs the scene from Gone s A by MGM after he directed The Women with (left to right) Joan Fontaine, Norma p with the Wind in which Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) ascends the staircase at Shearer, Mary Boland and Paulette Goddard. The studio made sure there was not a Twelve Oaks and Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) sees her for the first time. The set single male character in the film, including the extras and the animals. was built on stage 16 at Selznick International Studios in Culver City. ight) AM R M ection; (Botto LL o c ett R ve e eft) L M ection; (Botto LL o c BAL o k M/ g znick/M L e s s A p WAR TIME: William Dieterle (right) directing Juarez, starring Paul Muni (center) CROSS COUNTRY: Cecil B.