Tibetan Buddhist Essentials: Volume Three / Venerable Tenzin Tharpa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in International Buddhist Organizations by the Example of the Organization Rigpa

grant reference number: 01UL1823X The decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in international Buddhist Organizations by the example of the organization Rigpa Anne Iris Miriam Anders Globalization and commercialization of Buddhism: the organization Rigpa Rigpa is an international Buddhist organization (Vajrayāna Buddhism) with currently 130 centers and groups in 41 countries (see Buddhistische Religionsgemeinschaft Hamburg e.V. c/o Tibetisches Zentrum e.V., Nils Clausen, Hermann-Balk- Str. 106, 22147 Hamburg, Germany : "Rigpa hat mittlerweile mehr als 130 Zentren und Gruppen in 41 Ländern rund um die Welt." in https://brghamburg.de/rigpa-e-v/ date of retrieval: 5.11.2020) Rigpa in Austria: centers in Vienna and Salzburg see https://www.rigpa.de/zentren/daenemark-oesterreich-tschechien/ date of retrieval: 27.10.2020 Rigpa in Germany: 19 centers see https://www.rigpa.de/aktuelles/ date of retrieval: 19.11.2019 Background: globalization, commercialization and decontextualization of (Vajrayāna) Buddhism Impact: of decontextualization of terms and neologisms is the rationalization of economical, emotional and physical abuse of people (while a few others – mostly called 'inner circles' in context - draw their profits) 2 contents of the presentation I. timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa II. testimonies of probands from the organization Rigpa (in the research project TransTibMed) III. impact of decontextualizing concepts of Vajrayāna Buddhism and cross-group neologisms in international Buddhist organizations IV. additional citations in German language V. references 3 I) timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa 1. timeline of crucial events (starting 1994, 2017- summer 2018) (with links to the documents) 2. analysis of decontextualized concepts, corresponding key dynamics and neologisms 3. -

Mt. Kailash Pilgrimage Kora Grand Tour

MT. KAILASH PILGRIMAGE KORA GRAND TOUR Tashi delek! Tibetan Guide Travel Tours is a small travel agency based in Lhasa. We always work hard and take responsible for our clients by using local services as much as possible. Of course we use Tibetan drivers and tour guides. Who are experienced, have rich knowledge about Tibetan culture and also excellent attitude. We are confident that you would not be disappointed if you choose our services letting us show you our mother land. Proposed itinerary Day 1: Lhasa arrival [3650m] Upon arrival in Lhasa you will be welcomed by your English-speaking Tibetan Guide and Tibetan Driver who will bring you to your hotel. Acclimatization to high altitude: please, drink lots of water and take plenty of rest in order to minimize altitude sickness. Overnight at Shambhala Palace or House of Shambhala Hotel, which are a Tibetan style hotel located in Lhasa city center (Barkhor) Day 2: Lhasa sightseeing We begin visiting Ramoche Temple, built in honor of the image of Jowo Rinpoche that Chinese princess Wencheng brought by marrying Songtsen Gampo, the first king of Buddhist doctrine and who unified the Tibetan empire in the 7th century. Thereafter, we continue with Jokhang Temple, the most sacred monastery in Tibet. It was also founded in the 7th century by Songtsen Gampo. Later you can explore the surrounding Barkhor old quarter and spend time walking around Jokhang Temple following pilgrims from all over the Tibetan plateau. In the afternoon we go to Sera Monastery, one of three great universities of Gelugpa Sect. We will attend the debating session of the monks. -

YESHE MELONG “Mirror of Wisdom” NEWSLETTER April 1998

YESHE MELONG “Mirror of Wisdom” NEWSLETTER April 1998 News and Advice from Gyatrul Rinpoche A Brief Prayer that Spontaneously Fulfills All Wishes EMAHO! KON CHOG TSA SUM DE SHEK KUN DÜ PAL NYIK DÜ DRO WA GON MED KYAB CHIG PU TÜK JE LÖG TAR NYUR WA’I TÖD TRENG TSAL MAHA GURU PEDMA HERUKAR MÖ GÜ DÜNG SHÜK DRAG PÖ SOL WA DEB DRA DON GEK DANG BAR CHED JAD PUR LOK MA RÜNG GYAL SEN JÜNG PO DAM LA TOK SAM PA LHÜN GYI DRÜB PAR CHIN GYI LOB EMAHO! O Guru Rinpoche, in your glory you embody Buddha, Dharma and Sangha; Lama, Yidam and Khandro; and all the Sugatas, the sole refuge of beings, who are without protection in this dark age. Your compassion is as swift as lightening, Töd Treng Tsal. Maha Guru, wrathful Pedma Heruka, with fervent longing and devotion, we pray to you. Avert enemies, obstructing forces, obstacle-makers, curses and spells. Bring all negative forces—gyalpo, senmo and jungpo demons—under your subjugation. Grant your blessings so that all our wishes be spontaneously fulfilled! Tashi Delek! The old Fire Ox has gone away. He’s wagging his tail at us, therefore we are getting lots of stormy weather from East to West. Hopefully we’ll make it out okay because now the golden Earth Tiger is here. So, I’d like to say to everyone, “Happy New Year!” I am in Hawaii now, everything is fine. My feet are getting better, but I still have a slight problem with my shoulder. Everyday I swim with the fish, and I have lots of friends—mostly around three-years-old—that I play with in the water. -

These Are Raw Transcripts That Have Not Been Edited in Any Way, and May Contain Errors Introduced by the Volunteer Transcribers

These are raw transcripts that have not been edited in any way, and may contain errors introduced by the volunteer transcribers. Please refer to the audio on The Knowledge Base website (http://www.theknowledgebase.com) for the original teachings. The Asian Classics Institute Course XIII: The Art of Reasoning Taught by Geshe Michael Roach Class One: Why Study the Art of Reasoning [mandala] [refuge] Okay. Welcome. This is something like class number thirteen, okay, course number thirteen. When we started the courses, we , [unclear] and I went out and we bought six chairs at Ikea in New Jersey and brought it back in a Honda and I figured if we could make six good translators it would be a big achievement you know. So I’m happy to see that there are many people here. Tonight we’re gonna study Buddhist logic. We’re gonna start Buddhist logic. I waited twelve courses, thirteen courses to start Buddhist logic because I was afraid ure my first job is to sell you on the idea of studying Buddhist logic and then maybe you won’t run away to like the third class or something. So, I’ll tell you the story about Gyaltseb Je. Gyaltseb Je was the main disciple of Je Tsongkapa. Je Tsongkapa is really the beginning of our lineage and he was the teacher of the first Dalai Lama. His dates are 1357 – 1419, okay. Gyaltseb Je – the word Gyaltseb means regent,meaning he took over the show after Je Tsongkapa passed away. He was assigned by Je Tsongkapa. -

Big Love: Mandala Magazine Article

LAMA YESHE, PASHUPATINATH TEMPLE, NEPAL, 1980. PHOTO BY TOM CASTLES, COURTESY OF LAMA YESHE WISDOM ARCHIVE. 26 MANDALA | July - December 2019 A MONUMENTAL ACCOMPLISHMENT: THE MAKING OF Big Love BY LAURA MILLER The creation of FPMT founder Lama Yeshe’s official biography has been a monumental task. Work on the forthcoming book, Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe, has spanned three decades. To understand the significance of this project as it draws to a close, Mandala talked to three key people, all early students of Lama Yeshe, about the production of the book: Adele Hulse, Big Love’s author; Peter Kedge, who initiated and helped fund the project; and Nicholas Ribush, who is overseeing the book’s publication at the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe begins with a refugee Tibetan monks. Together, the two lamas encountered their simple dedication: “This book is dedicated to you, the reader. first Western student, Zina Rachevsky, in 1967 in Darjeeling. The If you met Lama during your life, may you feel his presence here. following year, they went to Nepal, where they soon established If you never met Lama, then come with us—walk up the hill to Kopan Monastery on the outskirts of Kathmandu and later Kopan and meet Lama Yeshe, as thousands did, without knowing founded the international FPMT organization. anything of Buddhism or Tibet. That came later.” “Since then, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been to many Within the biography’s nearly 1,400 pages, Lama Yeshe comes countries and now has a great reputation and has received many to life. -

The Tibetan Book of the Dead: Its History and Controversial Aspects of Its Contents

The Tibetan Book of the Dead: Its History and Controversial Aspects of its Contents Michael Nahm, Ph.D. Freiburg, Germany ABSTRACT: In recent decades, the Tibetan Book of the Dead (TBD) has attracted much attention from Westerners interested in Eastern spirituality and has been discussed in the literature on dying and near-death experiences. However, the history of the TBD has practically been ignored in that literature up to now. This history has been elaborated in detail by Tibetologist Bryan Cuevas (2003). To bring this history to the attention of scholars in the field of near-death studies, I present in this paper a summary of the TBD’s development based primarily on the work of Cuevas (2003). The summary shows that the TBD was gradually elaborated within a specific Tibetan Buddhist context, the Dzokchen tradition. In comparing features of first-hand reports of the death and dying process as reported in the TBD with those reported in four other categories—Tibetan délok, near-death experiencers, mediums, and children who remember previous lives— I find that some features are consistent but that other key features are not. Be- cause it seems likely that inconsistent features of the TBD reflect idiosyncratic dying and afterlife concepts of the Dzokchen tradition, scholars in the field of near-death studies and others should be careful about adopting the contents of the TBD without question. KEY WORDS: Tibetan Book of the Dead, Clear Light, bardo, délok, near-death experience Michael Nahm, Ph.D., is a biologist. After conducting research for several years in the field of tree physiology, he is presently concerned with developing improved strate- gies for harvesting woody plants for energetic use. -

An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism. Notes

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A. K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS L. M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University of Vienna Patiala, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, fapan Bardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson FJRN->' Volume 6 1983 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES A reconstruction of the Madhyamakdvatdra's Analysis of the Person, by Peter G. Fenner. 7 Cittaprakrti and Ayonisomanaskdra in the Ratnagolravi- bhdga: Precedent for the Hsin-Nien Distinction of The Awakening of Faith, by William Grosnick 35 An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism (Notes Contextualizing the Kalacakra)1, by Geshe Lhundup Sopa 48 Socio-Cultural Aspects of Theravada Buddhism in Ne pal, by Ramesh Chandra Tewari 67 The Yuktisas(ikakdrikd of Nagarjuna, by Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti 94 The "Suicide" Problem in the Pali Canon, by Martin G. Wiltshire \ 24 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Buddhist and Western Philosophy, edited by Nathan Katz 141 2. A Meditators Diary, by Jane Hamilton-Merritt 144 3. The Roof Tile ofTempyo, by Yasushi Inoue 146 4. Les royaumes de I'Himalaya, histoire et civilisation: le La- dakh, le Bhoutan, le Sikkirn, le Nepal, under the direc tion of Alexander W. Macdonald 147 5. Wings of the White Crane: Poems of Tskangs dbyangs rgya mtsho (1683-1706), translated by G.W. Houston The Rain of Wisdom, translated by the Nalanda Transla tion Committee under the Direction of Chogyam Trungpa Songs of Spiritual Change, by the Seventh Dalai Lama, Gyalwa Kalzang Gyatso 149 III. -

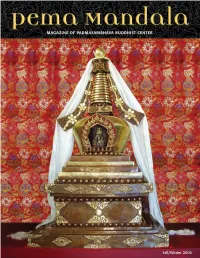

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

THE GROUND BENEATH HIS FEET an Artist's Sacred Sojourn In

THE GROUND BENEATH HIS FEET An Artist’s Sacred Sojourn in Western Tibet Modern life has made us busy every waking hour. The pervasive running out of time has become a sport befitting the strongest of urbanites. Success is measured by the ability to stay on top and we find purpose for our daily existence in the order and accumulation of things, which make us too preoccupied and anxious in the first place1. Then all of a sudden some tragic event with irreversible consequences turns everything on its head and shakes up the security of this hard‐earned status quo at its foundation. The void left in the aftermath creates an opening for a new vision to emerge in the mind’s awareness. It is often a desire for a more peaceful and spiritually focused way of being. The thought of this newfound horizon becomes so overwhelmingly vivid, and the urge to reach it so profound, that one takes in stride to make it a reality—above all else. Such a seismic shift catapulted Arthur Liou in search of something greater than life—he became a pilgrim on a quest. The vision to embark on an epic spiritual and creative journey into the Himalayan Mountains was triggered by the mysterious voice of a Tibetan singer heard in a bookstore in Taiwan. The soulfulness of her voice resonated deeply within his grieving heart, sparking an inner inkling for the distant land it came from. Not long after, a Buddhist monk friend showed him a photograph of Mount Kailash: the image looked astonishingly familiar to him despite having never been to this remote part of the world. -

The Nine Yanas

The Nine Yanas By Cortland Dahl In the Nyingma school, the spiritual journey is framed as a progression through nine spiritual approaches, which are typically referred to as "vehicles" or "yanas." The first three yanas include the Buddha’s more accessible teachings, those of the Sutrayana, or Sutra Vehicle. The latter six vehicles contain the teachings of Buddhist tantra and are referred to as the Vajrayana, or Vajra Vehicle. Students of the Nyingma teachings practice these various approaches as a unity. Lower vehicles are not dispensed with in favor of supposedly “higher” teachings, but rather integrated into a more refined and holistic approach to spiritual development. Thus, core teachings like renunciation and compassion are equally important in all nine vehicles, though they may be expressed in more subtle ways. In the Foundational Vehicle, for instance, renunciation involves leaving behind “worldly” activities and taking up the life of a celibate monk or nun, while in the Great Perfection, renunciation means to leave behind all dualistic perception and contrived spiritual effort. Each vehicle contains three distinct components: view, meditation, and conduct. The view refers to a set of philosophical tenets espoused by a particular approach. On a more experiential level, the view prescribes how practitioners of a given vehicle should “see” reality and its relative manifestations. Meditation consists of the practical techniques that allow practitioners to integrate Buddhist principles with their own lives, thus providing a bridge between theory and experience, while conduct spells out the ethical guidelines of each system. The following sections outline the features of each approach. Keep in mind, however, that each vehicle is a world unto itself, with its own unique philosophical views, meditations, and ethical systems. -

Spring 2002 Vol

The NYEMA Sun NYEMA Projects' semi-annual newsletter on humanitarian projects in eastern Tibet Spring 2002 Vol. 1, No. 1 A Letter from Venerable Lama Norlha In This Issue: Dear Friends: Letter from Venerable Lama Norlha.. 1 From the bottom of my heart, I thank you for your generosity and support in helping to improve the quality About NYEMA . .1 of life in my native land of Nangchen over the past few years. The people of Nangchen are also sincerely Monastic Initiative: grateful and every day see reminders of their Kala Rongo . 2 benefactors' compassion. Korche Monastery. 3 Affiliated Projects . I am pleased to introduce the first issue of NYEMA's .4 on-line newsletter, The NYEMA Sun. Amazing progress is being made in so many areas–from the Education Initiative . opening of Tibet's first monastic college for women at 5 Kala Rongo Monastery to supplying new beds and stoves in the student dormitories at Yonten Gatsal Ling Medical Initiative. Primary School. Future projects include building 6 residences for Nangchen's elderly population, expanding our satellite school program that has introduced literacy and basic math skills to children in remote areas, Community Initiative. providing medical training for women, and continuing .7 to expand the monastic institutions that are so important to serving their communities and preserving the Donation Form . .. language, religion and culture of Tibet. .8 I hope you enjoy the first edition of The NYEMA Sun If you would like to and visit our website often to follow our ongoing be notified via email of progress. Tashi Delek! future newsletters–as well as important new Sincerely, develop-ments in Nangchen–we cordially Lama Norlha invite you to join our Lama Norlha mailing list. -

Buddhism / Dalai Lama 99

Buddhism / Dalai Lama 99 Activating Bodhichitta and A Meditation on Compassion His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama Translated by Gonsar Rinpoche The awakening mind is the unsurpassable way to collect merit. To purify obstacles bodhicitta is supreme. For protection from interferences bodhicitta is supreme. It is the unique, all-encompassing method. Every kind of ordinary and supra-mundane power can be accomplished through bodhicitta. Thus, it is absolutely precious. Although compassion is cultivated in one’s own mind, the embodiment of it is the deity known as Avalokiteshvara (Tib. Chan-re- PY: 1979,2006 zig). The various aspects that are visualized in meditation practices and 5.5 X 8.5 represented in images and paintings are merely the interpretative forms of 80 pages Avalokitephvara, whereas the actual definitive form is compassion itself. ` 140 paperback ISBN: 81-86470-52-2 Awakening the Mind, Lightening the Heart His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama Edited by Donald S.Lopez,Jr. Awakening the Mind, Lightening the Heart is His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s gentle and profoundly eloquent instruction for developing the basis of the spiritual path: a compassionate motive. With extraordinary grace and insight, His Holiness shows how the Tibetan Buddist teachings on compassion can be practiced in our daily lives through simple meditations that directly relate to past and present PY: 2008 relationships. 5.5 X 8.5 This illuminating and highly accessible guide offers techniques for 178 pages deepening and heightening compassion in our lives and the world around ` 215 paperback us. ISBN: 81-86470-68-9 Commentary on the Thirty Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama Translated by Acharya Nyima Tsering Ngulchu Gyalse Thogmed Zangpo’s The Thirty Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva is one of Tibetan Buddhism’s most popular texts, incorporated in the Mind Training text and also able to be explained according to the Lam Rim tradition.