Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, RG, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

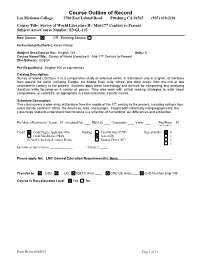

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

Staff Working Paper No. 845 Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, R-G, and the ‘Suprasecular’ Decline, 1311–2018 Paul Schmelzing

CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 -

Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560–1720

Edited by Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Marko and Karonen Petri by Edited Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720 provides fresh insights into the state-building process in Sweden. During this transitional period, many far-reaching administrative reforms were the Swedish at Agency Personal Age of Greatness 1560–1720 Greatness of Age carried out, and the Swedish state developed into a prime example of the ‘power-state’. Personal Agency In early modern studies, agency has long remained in the shadow of the study of structures and institutions. State building in Sweden at the Swedish Age of was a more diversified and personalized process than has previously been assumed. Numerous individuals were also important actors Greatness 1560–1720 in the process, and that development itself was not straightforward progression at the macro-level but was intertwined with lower-level Edited by actors. Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Editors of the anthology are Dr. Petri Karonen, Professor of Finnish history at the University of Jyväskylä and Dr. Marko Hakanen, Research Fellow of Finnish History at the University of Jyväskylä. studia fennica historica 23 isbn 978-952-222-882-6 93 9789522228826 www.finlit.fi/kirjat Studia Fennica studia fennica anthropologica ethnologica folkloristica historica linguistica litteraria Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. -

Letters from New Spain, Mid 1500S

Library of Congress Letters Home: Correspondence from Spanish colonists in Mexico City and Puebla to relatives * in Spain, 1558-1589 Mexico City and Puebla, detail of A. Ysarti, Provincia d[e] S. Diego de Mexico EXCERPTS en la nueba Espana . , ca. 1682 Antonio Mateos, a farmer in Puebla, to his wife in Spain, 1558 Very longed-for lady wife: doing the best thing for you and me. Give my About a year and a half ago I wrote you greetings to my sisters and to your brother and greatly desiring to know about you and the health mine and to my nephews, and also to all of your of yourself and my son Antón Mateos, and also cousins and relatives and neighbors, and greet about my sisters and your brother and mine Antón everyone who asks for me. I haven’t heard from Pérez, but I have never had a letter or reply since my cousins for four years and nine months; they you wrote when I sent you money by Juan de left Mexico City and went I don’t know where, Ocampo. With the desire to prepare for your nor do I know if they are alive or dead. No more, arrival, I went to the valley of Atlixco, where they but may our Lord keep you in his hand for me. grow two crops of wheat a year, one irrigated and the other watered by rainfall; I thought that we could be there the rest of our Library of Congress lives. I was a farmer for a year in company with another farmer there; for the future I had found lands and bought four pair of oxen and everything necessary for our livelihood, since the land is the most luxuriant, and plenteous and abundant in grain, that there is in all New Spain. -

The Evolution of Hospitals from Antiquity to the Renaissance

Acta Theologica Supplementum 7 2005 THE EVOLUTION OF HOSPITALS FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE RENAISSANCE ABSTRACT There is some evidence that a kind of hospital already existed towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC in ancient Mesopotamia. In India the monastic system created by the Buddhist religion led to institutionalised health care facilities as early as the 5th century BC, and with the spread of Buddhism to the east, nursing facilities, the nature and function of which are not known to us, also appeared in Sri Lanka, China and South East Asia. One would expect to find the origin of the hospital in the modern sense of the word in Greece, the birthplace of rational medicine in the 4th century BC, but the Hippocratic doctors paid house-calls, and the temples of Asclepius were vi- sited for incubation sleep and magico-religious treatment. In Roman times the military and slave hospitals were built for a specialised group and not for the public, and were therefore not precursors of the modern hospital. It is to the Christians that one must turn for the origin of the modern hospital. Hospices, originally called xenodochia, ini- tially built to shelter pilgrims and messengers between various bishops, were under Christian control developed into hospitals in the modern sense of the word. In Rome itself, the first hospital was built in the 4th century AD by a wealthy penitent widow, Fabiola. In the early Middle Ages (6th to 10th century), under the influence of the Be- nedictine Order, an infirmary became an established part of every monastery. -

Medieval Heritage and Pilgrimage Walks

Medieval Heritage and Pilgrimage Walks Cleveland Way Trail: walk the 3 miles from Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire to Helmsley Castle and tread in the footsteps of medieval Pilgrims along what’s now part of the Cleveland Way Trail. Camino de Santiago/Way of St James, Spain: along with trips to the Holy Land and Rome, this is the most famous medieval pilgrimage trail of all, and the most well-travelled in medieval times, at least until the advent of Black Death. Its destination point is the spot St James is said to have been buried, in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Today Santiago is one of UNESCO’s World Heritage sites. Read more . the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela holds a Pilgrims’ Mass every day at noon. Walk as much or as little of it as you like. Follow the famous scallop shell symbols. A popular starting point, both today and in the Middle Ages, is either Le Puy in the Massif Central, France OR the famous medieval Abbey at Cluny, near Paris. The Spanish start is from the Pyrenees, on to Roncevalles or Jaca. These routes also take in the Via Regia and/or the Camino Frances. The Portuguese way is also popular: from the Cathedrals in either Lisbon or Porto and then crossing into Falicia/Valenca. At the end of the walk you receive a stamped certifi cate, the Compostela. To achieve this you must have walked at least 100km or cycled for 200. To walk the entire route may take months. Read more . The route has inspired many TV and fi lm productions, such as Simon Reeve’s BBC2 ‘Pilgrimage’ series (2013) and The Way (2010), written and directed by Emilio Estevez, about a father completing the pilgrimage in memory of his son who died along the Way of St James. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Women's Clothing in the 18Th Century

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions A Peek Inside Mrs. Derby’s Clothes Press: Women’s Clothing in the 18th Century In the parlor of the Derby House is a por- trait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, wearing her finest apparel. But what exactly is she wearing? And what else would she wear? This edition of Pickled Fish focuses on women’s clothing in the years between 1760 and 1780, when the Derby Family were living in the “little brick house” on Derby Street. Like today, women in the 18th century dressed up or down depending on their social status or the work they were doing. Like today, women dressed up or down depending on the situation, and also like today, the shape of most garments was common to upper and lower classes, but differentiated by expense of fabric, quality of workmanship, and how well the garment fit. Number of garments was also determined by a woman’s class and income level; and as we shall see, recent scholarship has caused us to revise the number of garments owned by women of the upper classes in Essex County. Unfortunately, the portrait and two items of clothing are all that remain of Elizabeth’s wardrobe. Few family receipts have survived, and even the de- tailed inventory of Elias Hasket Derby’s estate in 1799 does not include any cloth- ing, male or female. However, because Pastel portrait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, c. 1780, by Benjamin Blythe. She seems to be many other articles (continued on page 8) wearing a loose robe over her gown in imitation of fashionable portraits. -

Puritan New England: Plymouth

Puritan New England: Plymouth A New England for Puritans The second major area to be colonized by the English in the first half of the 17th century, New England, differed markedly in its founding principles from the commercially oriented Chesapeake tobacco colonies. Settled largely by waves of Puritan families in the 1630s, New England had a religious orientation from the start. In England, reform-minded men and women had been calling for greater changes to the English national church since the 1580s. These reformers, who followed the teachings of John Calvin and other Protestant reformers, were called Puritans because of their insistence on purifying the Church of England of what they believed to be unscriptural, Catholic elements that lingered in its institutions and practices. Many who provided leadership in early New England were educated ministers who had studied at Cambridge or Oxford but who, because they had questioned the practices of the Church of England, had been deprived of careers by the king and his officials in an effort to silence all dissenting voices. Other Puritan leaders, such as the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, came from the privileged class of English gentry. These well-to-do Puritans and many thousands more left their English homes not to establish a land of religious freedom, but to practice their own religion without persecution. Puritan New England offered them the opportunity to live as they believed the Bible demanded. In their “New” England, they set out to create a model of reformed Protestantism, a new English Israel. The conflict generated by Puritanism had divided English society because the Puritans demanded reforms that undermined the traditional festive culture. -

Farm Laborers' Wages in England 1208-1850

THE LONG MARCH OF HISTORY: FARM LABORERS’ WAGES IN ENGLAND 1208-1850 Gregory Clark Department of Economics UC-Davis, Davis CA 95616 [email protected] Using manuscript and secondary sources, the paper calculates real day wages for male agricultural laborers in England from 1208 to 1850. Both nominal wages and the cost of living move differently than is suggested by the famous Phelps-Brown and Hopkins series on building craftsmen. In particular farm laborers real wages were only half as much in the pre-plague years as would be implied by the PBH index. The PBH series implied that the English economy broke from the stasis of the medieval period only in the late eighteenth century. The real wage calculated here suggest that the productivity of the economy began growing from the medieval level at least a century earlier in the mid seventeenth century. INTRODUCTION The wage history of pre-industrial England is unusually well documented for a pre- industrial economy. The relative stability of English institutions after 1066, and the early development of markets, allowed a large number of documents with wages and prices to survive in the records of churches, monasteries, colleges, charities, and government. These documents have been the basis of many studies of pre-industrial wages and prices: most notably those of James E. Thorold Rogers, William Beveridge, Elizabeth Gilboy, Henry Phelps-Brown and Sheila Hopkins, Peter Bowden, and David Farmer.1 But only one of these studies, that of Phelps- Brown and Hopkins, attempted to measure real wages over the whole period. Using the wages of building craftsmen Phelps-Brown and Hopkins constructed a real wage series from 1264 to 1954 which is still widely quoted.2 This series famously established two things. -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies.