Sample File This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riche Productions Current Slate

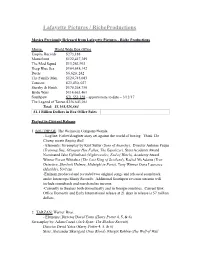

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

NICHOLAS LUNDY Production Designer Nicholaslundy.Com

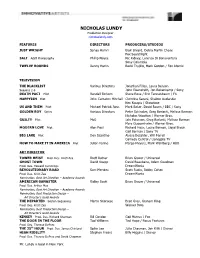

NICHOLAS LUNDY Production Designer nicholaslundy.com FEATURES DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS JUST WRIGHT Sanaa Hamri Blair Breard, Debra Martin Chase Fox Searchlight SALT Add’l Photography Phillip Noyce Ric Kidney, Lorenzo Di Bonaventura Sony Columbia TWELVE ROUNDS Renny Harlin Becki Trujillo, Mark Gordon / Fox Atomic TELEVISION THE BLACKLIST Various Directors Jonathan Filley, Laura Benson Seasons 2-6 John Eisendrath, Jon Bokenkamp / Sony DEATH PACT Pilot Randall Einhorn Steve Rose / Eric Tannenbaum / FX HAPPYISH Pilot John Cameron Mitchell Christine Sacani, Shalom Auslander Ken Kwapis / Showtime US AND THEM Pilot Michael Patrick Jann Mark Baker, David Rosen / BBC / Sony GOLDEN BOY Series Various Directors Peter Schindler, Greg Berlanti, Melissa Berman Nicholas Wootton / Warner Bros. GUILTY Pilot McG Iain Paterson, Greg Berlanti, Melissa Berman Marc Guggenheim / Warner Bros. MODERN LOVE Pilot Alan Poul Richard Heus, Laura Benson, Lloyd Braun Gail Berman / Sony TV BIG LAKE Pilot Don Scardino Alysse Bezahler, Will Ferrell Comedy Central / Lionsgate TV HOW TO MAKE IT IN AMERICA Pilot Julian Farino Margo Meyers, Mark Wahlberg / HBO ART DIRECTOR TOWER HEIST Prod. Des. Kristi Zea Brett Ratner Brian Grazer / Universal GHOST TOWN David Koepp David Beaubaire, Adam Goodman Prod. Des. Howard Cummings DreamWorks REVOLUTIONARY ROAD Sam Mendes Scott Rudin, Bobby Cohen Prod. Des. Kristi Zea DreamWorks Nomination, Best Art Direction – Academy Awards AMERICAN GANGSTER Ridley Scott Brian Grazer / Universal Prod. Des. Arthur Max Nomination, Best Art Direction – Academy Awards Nomination, Best Production Design – Art Director’s Guild Awards THE DEPARTED Boston Sequences Martin Scorsese Brad Grey, Graham King Prod. Des. Kristi Zea Warner Bros. Nomination, Best Production Design – Art Director’s Guild Awards KINSEY Prod. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Absolute Power

FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 12, 2019 5:37:02 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of October 20 - 26, 2019 Absolute power Jason Clarke and Helen Mirren in “Catherine the Great” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 Dame Helen Mirren (“Collateral Beauty,” 2016) explores the public and private tale of Catherine the Great’s rulership as she reached the end of her life in the four-part period drama “Catherine the Great,” premiering Monday, Oct. 21, on HBO. The series tells her glorious, politically victorious story, while also outlining the controversy and eroticism that challenged her luxurious, golden court. To advertise here WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS please call ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 (978) 946-2375 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 12, 2019 5:37:03 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson NESN Sunday 6:00 p.m. NESN Bruins Classics NHL Hockey NCAA Massachusetts - 9:00 p.m. SHOW Boxing Erickson Salem Londonderry 6:30 a.m. -

Collective of Heroes: Arrow's Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2016 Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy Alyssa G. Kilbourn St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Kilbourn, Alyssa G., "Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy" (2016). Culminating Projects in English. 73. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Collective of Heroes: Arrow’s Move Toward a Posthuman Superhero Fantasy by Alyssa Grace Kilbourn A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Rhetoric and Writing December, 2016 Thesis Committee: James Heiman, Chairperson Matthew Barton Jennifer Tuder 2 Abstract Since 9/11, superheroes have become a popular medium for storytelling, so much so that popular culture is inundated with the narratives. More recently, the superhero narrative has moved from cinema to television, which allows for the narratives to address more pressing cultural concerns in a more immediate fashion. Furthermore, millions of viewers perpetuate the televised narratives because they resonate with the values and stories in the shows. Through Fantasy Theme Analysis, this project examines the audience values within the Arrow’s superhero fantasy and the influence of posthumanism on the show’s superhero fantasy. -

Arrow: Fatal Legacies Ebook

ARROW: FATAL LEGACIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marc Guggenheim | 384 pages | 06 Feb 2018 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781783295210 | English | London, United Kingdom Arrow: Fatal Legacies PDF Book Titan Books. The Parenting Book Guide. Books will be free of page markings. Shuzo Oshimi. Arrowverse 4 books. See details for additional description. Download Hi Res. Good stuff, Maynard. Aggiungi al carrello. More Details The Flash: Season Zero. Arrow Ser. Thanks for reading Katie. Sensitively and carefully as if the character is fragile- which she is. Malcolm Merlyn. Sometimes, I wondered if Tuck knew what the words he was writing actually meant. We are made by history. Sailor Moon Eternal Edition 7. Works can belong to more than one series. But personally I love Arrow, even through it's low points. It was almost a 2. Yao Fei. In this one, Annie is a toddler who is starting to develop her spider powers much to the dismay of her parents. Hope William will be okay. CherCher rated it liked it Apr 14, I will continue to look for Titan Books, this just wasn't a favorite. It did a really great job of filling in the missing six months between the end of season 5 and the beginning of season 6. Good action book Action, I would like that had a little more interaction between Oliver and William. Be the first to write a review About this product. Nyssa al Ghul. Return to Book Page. Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. I read the 3 books in the Deacon Chalk series and found each one tougher to read than the last. -

C. Kim Miles Csc, Mysc, Asc Director of Photography Bc Resident / Iatse 669 Online Reel

C. KIM MILES CSC, MYSC, ASC DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY BC RESIDENT / IATSE 669 ONLINE REEL TELEVISION / NEW MEDIA STUDIO/COMPANY DIRECTOR/PRODUCERS YELLOWJACKETS (Season I) Showtime D: Karyn Kusama EP: Drew Comins, Kayrn Kusama, Ashley Lyle, Bart Nickerson LOST OLLIE (Season I) Netflix D: Peter Ramsey EP: Shawn Levy, Josh Barry, Brandon Oldenburg, Lampton Enochs, Shannon Tindle, Peter Ramsey P: Emily Morris, Brent Crowell HOME BEFORE DARK (Season II) Paramount Television / Apple+ EP: Dana Fox, Jon M. Chu PROJECT BLUE BOOK (Seasons I & II) A+E Studios and Compari Entertainment EP: Robert Zemeckis, For History Channel Sean Jablonski **WINNER OF THE 2020 ASC AWARD FOR CINEMATOGRAPHY IN ONE EPISODE OF A SERIES FOR COMMERICAL TELEVISION LOST IN SPACE (Season II) NETFLIX / Legendary Television EP: Zack Estrin, Burk Sharpless THE FLASH (Seasons I, II & III) Warner Bros. Television EP: Greg Berlanti, Todd Helbing *Director for Episodes #305, #502 PRISON BREAK (Season V) 20th Century FOX Television EP: Steve Beers, Vaun Wilmott Add’l photography ARROW (Season II – 5 eps) Warner Bros. Television EP: Greg Berlanti, Marc Guggenheim MORTAL KOMBAT LEGACY Warner Premiere / Warner New Media D: Kevin Tancharoen EP: Lance Sloan, Tim Carter DARWIN’S BRAVE NEW WORLD CBC / ABC / Screenworld Australia D: Lisa Matthews EP: Andrew Ferns, Michael Bluett ALIENATED (Seasons I & II) Chum Television D: Mark Sawers, Trent Carlson FEATURE FILMS STUDIO /COMPANY DIRECTOR WELCOME TO MARWEN Universal Pictures / Robert Zemeckis Dreamworks Entertainment GRUDGE (Additional Photography) Sony Screen Gems / Nicolas Pesce Ghost House Pictures BEETHOVEN ‘S TREASURE Universal 1440 Entertainment Ron Oliver THE PACKAGE MPCA Jesse V. Johnson BLONDE AND BLONDER Paradigm Entertainment Bob Clark THE FRENCH GUY Global Mechanic Ann Marie Fleming HANK WILLIAMS FIRST NATION Peace Country Films Aaron Sorensen A DENNIS THE MENACE CHRISTMAS Warner Bros Premiere Ron Oliver ALIEN AGENT Fries Entertainment Jesse V. -

LGBTQ+ GUIDE to COMIC-CON@HOME 2021 Compiled by Andy Mangels Edited by Ted Abenheim Collage Created by Sean (PXLFORGE) Brennan

LGBTQ+ GUIDE TO COMIC-CON@HOME 2021 Compiled by Andy Mangels Edited by Ted Abenheim Collage created by Sean (PXLFORGE) Brennan Character Key on pages 3 and 4 Images © Respective Publishers, Creators and Artists Prism logo designed by Chip Kidd PRISM COMICS is an all-volunteer, nonprofit 501c3 organization championing LGBTQ+ diversity and inclusion in comics and popular media. Founded in 2003, Prism supports queer and LGBTQ-friendly comics professionals, readers, educators and librarians through its website, social networking, booths and panel presentations at conventions. Prism Comics also presents the annual Prism Awards for excellence in queer comics in collaboration with the Queer Comics Expo and The Cartoon Art Museum. Visit us at prismcomics.org or on Facebook - facebook.com/prismcomics WELCOME We miss conventions! We miss seeing comics fans, creators, pros, panelists, exhibitors, cosplayers and the wonderful Comic-Con staff. You’re all family, and we hope everyone had a safe and productive 2020 and first half of 2021. In the past year and a half we’ve seen queer, BIPOC, AAPI and other marginalized communities come forth with strength, power and pride like we have not seen in a long time. In the face of hate and discrimination we at Prism stand even more strongly for the principles of diversity and equality on which the organization was founded. We stand with the Black, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Indigenous, Latinx, Transgender communities and People of Color - LGBTQ+ and allies - in advocating for inclusion and social justice. Comics, graphic novels and arts are very powerful mediums for marginalized voices to be heard. -

Justice League

DC Rethinks Its Universe While DC Entertainment has won big in comics, TV, and games, they’ve struggled at the movies. Does Wonder Woman show the way forward? By Abraham Riesman 09/29/2017 8:00 am Share Tweet Pin It Email Comment here’s a paradox at DC Entertainment, and it can be summed up by looking at two men who wear Superman’s tights. One of them is Tyler Hoechlin, a dreamy American who T portrays the Man of Steel on the small screen as part of the TV show Supergirl. The other is Henry Cavill, a statuesque Brit who plays him in DC’s big-screen outings like Man of Steel, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, and this fall’s mega-tentpole Justice League. Hoechlin’s Superman has a sterling image among the public: He’s not a series regular, but when he does show up, fans go gaga for him, much as they salivate over the well-reviewed show, in general. Cavill’s Supes, on the other hand, has an image-control problem: All of his movies so far have been met with at least a certain amount of critical disdain, if not outright derision. In short, one Superman is flying high; the other is experiencing turbulence. It’s DC Entertainment in microcosm: When it comes to movies, there’s chronic bad buzz; elsewhere, things are going swimmingly. Once known as DC Comics, a 2009 restructuring made the Warner Bros.–owned company more than just a comics publisher — they now also work in coalition with the rest of Warner to produce superhero content in TV, games, consumer products, and films. -

Comic Book Fandom

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2015-01-01 Comic Book Fandom: An Exploratory Study Into The orW ld Of Comic Book Fan Social Identity Through Parasocial Theory Anthony Robert Ramirez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Ramirez, Anthony Robert, "Comic Book Fandom: An Exploratory Study Into The orldW Of Comic Book Fan Social Identity Through Parasocial Theory" (2015). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1131. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1131 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMIC BOOK FANDOM: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY INTO THE WORLD OF COMIC BOOK FAN SOCIAL IDENTITY THROUGH PARASOCIAL THEORY ANTHONY R. RAMIREZ Department of Communication APPROVED: _____________________________ Roberto Avant-Mier, Ph.D., Chair _____________________________ Thomas Ruggiero, Ph.D. _____________________________ Brian Yothers, Ph.D. ___________________________ Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Anthony Robert Ramirez 2015 COMIC BOOK FANDOM: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY INTO THE WORLD OF COMIC BOOK FAN SOCIAL IDENTITY THROUGH PARASOCIAL THEORY by ANTHONY R. RAMIREZ B.F.A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2015 ABSTRACT Comic books and their extensive lineup of characters have invaded all types of media forms, making comics a global media phenomenon that are having a wider profile in media and popular culture. -

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

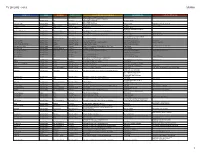

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V.