Edward Elgar : a Composer at Work; a Study of His Creative Processes As Seen Through His Sketches and Proof Corrections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

≥ Elgar Sea Pictures Polonia Pomp and Circumstance Marches 1–5 Sir Mark Elder Alice Coote Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Sea Pictures, Op.37 1

≥ ELGAR SEA PICTURES POLONIA POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES 1–5 SIR MARK ELDER ALICE COOTE SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) SEA PICTURES, OP.37 1. Sea Slumber-Song (Roden Noel) .......................................................... 5.15 2. In Haven (C. Alice Elgar) ........................................................................... 1.42 3. Sabbath Morning at Sea (Mrs Browning) ........................................ 5.47 4. Where Corals Lie (Dr Richard Garnett) ............................................. 3.57 5. The Swimmer (Adam Lindsay Gordon) .............................................5.52 ALICE COOTE MEZZO SOPRANO 6. POLONIA, OP.76 ......................................................................................13.16 POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES, OP.39 7. No.1 in D major .............................................................................................. 6.14 8. No.2 in A minor .............................................................................................. 5.14 9. No.3 in C minor ..............................................................................................5.49 10. No.4 in G major ..............................................................................................4.52 11. No.5 in C major .............................................................................................. 6.15 TOTAL TIMING .....................................................................................................64.58 ≥ MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CBE LEADER LYN FLETCHER WWW.HALLE.CO.UK -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Acts of the Apostles Bible Study Lesson # 1 “What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in the Church?”

Acts of the Apostles Bible Study Lesson # 1 “What is the role of the Holy Spirit in the Church?” Introduction The gospel writer Luke in his second volume, called “The Acts of the Apostles” or simply “Acts,” is giving Theophilus an account of the birth of the Church, how it organized and solved its problems, and its subsequent spreading of the good news of Jesus Christ following his ascension. Luke makes it clear that the Church did not start on account of any human endeavor but by the power of the Holy Spirit that Jesus promised to give. Because of the power of the Holy Spirit, the Church became an agent for change, bore witness to the faith and became a radically unique and diverse community. From Jerusalem at Pentecost, the Holy Spirit enabled the Church to spread to Syria, Asia, Europe and Africa. The Holy Spirit also took a wide range of people, from a Galilean fisherman to a learned scholar, to cities and towns throughout the Roman Empire to preach the good news, heal, teach and demonstrate God’s love. Despite the apostle’s imprisonment and beatings, and an occasional riot, the band of faithful managed to grow in spite of their persecution. The growth of the Church Luke credits to the guiding work of the Holy Spirit that cannot be bottled or contained. Women, children, Jews and Gentiles were coming together into a new sense of community and purpose through the common experience of encountering the transformative power of Jesus Christ. This bible study is produced to not only help the faithful understand God’s plan for the expansion of the Church but to challenge individual Christians as well as faith communities to seek to understand what God is asking them to do in light of God’s current movement of the Holy Spirit. -

Vol. 17, No. 3 December 2011

Journal December 2011 Vol.17, No. 3 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] December 2011 Vol. 17, No. 3 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Gerald Lawrence, Elgar and the missing Beau Brummel Music 4 Vice-Presidents Robert Kay Ian Parrott Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Elgar and Rosa Newmarch 29 Diana McVeagh Martin Bird Michael Kennedy, CBE Michael Pope Book reviews Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Robert Anderson, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley 41 Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 46 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Simon Thompson Donald Hunt, OBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE CD reviews 49 Andrew Neill Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Spenceley Sir Mark Elder, CBE 100 Years Ago 61 Chairman Steven Halls Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Gerald Lawrence in his Beau Brummel costume, from Messrs. William Elkin's published piano arrangement of the Minuet (Arthur Reynolds Collection). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Editorial required, are obtained. Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, cued into the text, and have captions. -

Journal September 1984

The Elgar Society JOURNAL ^■m Z 1 % 1 ?■ • 'y. W ■■ ■ '4 September 1984 Contents Page Editorial 3 News Items and Announcements 5 Articles: Further Notes on Severn House 7 Elgar and the Toronto Symphony 9 Elgar and Hardy 13 International Report 16 AGM and Malvern Dinner 18 Eigar in Rutland 20 A Vice-President’s Tribute 21 Concert Diary 22 Book Reviews 24 Record Reviews 29 Branch Reports 30 Letters 33 Subscription Detaiis 36 The editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views The cover portrait is reproduced by kind permission of National Portrait Gallery This issue of ‘The Elgar Society Journal’ is computer-typeset. The computer programs were written by a committee member, Michael Rostron, and the processing was carried out on Hutton -t- Rostron’s PDPSe computer. The font used is Newton, composed on an APS5 photo-typesetter by Systemset - a division of Microgen Ltd. ELGAR SOCIETY JOURNAL ISSN 0143-121 2 r rhe Elgar Society Journal 01-440 2651 104 CRESCENT ROAD, NEW BARNET. HERTS. EDITORIAL September 1984 .Vol.3.no.6 By the time these words appear the year 1984 will be three parts gone, and most of the musical events which took so long to plan will be pleasant memories. In the Autumn months there are still concerts and lectures to attend, but it must be admitted there is a sense of ‘winding down’. However, the joint meeting with the Delius Society in October is something to be welcomed, and we hope it may be the beginning of an association with other musical societies. -

Solving Elgar's Enigma

Solving Elgar's Enigma Charles Richard Santa and Matthew Santa On June 19, 1899, Elgar's opus 36, Variations on a Theme, was introduced to the public for the first time. It was accompanied by an unusual program note: It is true that I have sketched for their amusement and mine, the idiosyn crasies of fourteen of my friends, not necessarily musicians; but this is a personal matter, and need not have been mentioned publicly. The Varia tions should stand simply as a "piece" of music. The Enigma I will not explain-its "dark saying" must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set [of variations 1 another and larger theme "goes" but is not played ... So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some late dramas-e.g., Maeterlinck's "L'Intruse" and "Les sept Princesses" -the chief character is never on the stage. (Burley and Carruthers 1972:119) After this premier Elgar give hints about the piece's "Enigma;' but he never gave the solution outright and took the secret to his grave. Since that time scholars, music lovers, and cryptologists have been trying to solve the Enigma. Because the solution has not been discovered in spite of over 108 years of searching, many people have assumed that it would never be found. In fact, some have speculated that there is no solution, and that the promise of an Enigma was Elgar's rather shrewd way of garnering publicity for the piece. -

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal Script Not for Performance Use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations What Secret? Perusal script Not for performance use Copyright © 2010 Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Duplication and distribution prohibited. In addition to the orchestra and conductor: Five performers Edward Elgar, an Englishman from Worcestershire, 41 years old Actor 2 (female) playing: Caroline Alice Elgar, the composer's wife Carice Elgar, the composer's daughter Dora Penny, a young woman in her early twenties Snobbish older woman Actor 3 (male) playing: William Langland, the mediaeval poet Arthur Troyte Griffith (Ninepin), an architect in Malvern Richard Baxter Townsend, a retired adventurer William Meath Baker, a wealthy landowner George Robertson Sinclair, a cathedral organist August Jaeger (Nimrod), a German music-editor William Baker, son of William Meath Baker Old-fashioned musical journalist Pianist Narrator Page 1 of 21 ME 1 Orchestra, theme, from opening to figure 1 48" VO 1 Embedded Audio 1: distant birdsong NARRATOR The Malvern Hills... A nine-mile ridge of rock in the far west of England standing about a thousand feet above the surrounding countryside... From up here on a clear day you can see far into the distance... on one side... across the patchwork fields of Herefordshire to Wales and the Black Mountains... on another... over the river Severn... Shakespeare's beloved river Avon... and the Vale of Evesham... to the Cotswolds... Page 2 of 21 and... if you're lucky... to the north, you can just make out the ancient city of Worcesteri... and the tall square tower of its cathedral... in the shadow of which... Edward Elgar spent his childhood and his youth.. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Bible Study Guide on the Acts of the Apostles

Investigating the Word of God Acts Artist’s Depiction of the Apostle Paul Preaching at the Areopagus in Athens Gene Taylor © Gene Taylor, 2007. All Rights Reserved All lessons are based on the New King James Version, © Thomas Nelson, Inc. An Introduction to Acts The Author There are no serious doubts as to the authorship of the book of Acts of the Apostles. Luke is assigned as its author. As early as the last part of the 2nd century, Irenaeus cites passages so frequently from the Acts of the Apostles that it is certain that he had constant access to the book. He gives emphasis to the internal evidence of its authorship. Tertullian also ascribes the book to Luke, as does Clement of Alexandria. That Luke is the author of the book of Acts is evident from the following. ! The Preface of the Book. The writer addresses Theophilus (Luke 1:3), who is the same individual to whom the gospel of Luke was also directed, and makes reference to a “former treatise” which dealt with “all that Jesus began to do and to teach until the day he was received up” (1:1-2). This is very evidently a reference to the third gospel. ! The book of Acts and the gospel of Luke are identical in style, as a number of scholars have pointed out and demonstrated. ! The book of Acts comes as an historical sequel to the gospel of Luke, taking up with the very events, and at the point where the gospel of Luke concludes, namely the resurrection, the appearances following the resurrection, and the commissioning of the Apostles to the task for which they had been selected and trained by the Lord, and the ascension of Jesus. -

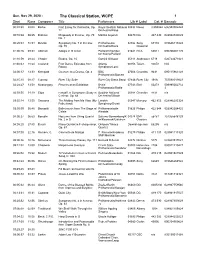

29, 2020 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Nov 29, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 08:08 Barber First Essay for Orchestra, Op. Royal Scottish National 08830 Naxos 8.559024 636943902424 12 Orchestra/Alsop 00:10:3808:25 Brahms Rhapsody in B minor, Op. 79 Martha Argerich 04470 DG 447 430 028944743029 No. 1 00:20:03 38:53 Dvorak Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Philharmonia 02982 Sony 67174 074646717424 Op. 70 Orchestra/Davis Classical 01:00:2609:33 Albinoni Adagio in G minor Paillard Chamber 01641 RCA 60011 090266001125 Orchestra/Paillard 01:10:59 28:44 Chopin Etudes, Op. 10 Garrick Ohlsson 05311 Arabesque 6718 026724671821 01:40:4318:24 Copland Four Dance Episodes from Atlanta 00356 Telarc 80078 N/A Rodeo Symphony/Lane 02:00:3713:33 Korngold Overture to a Drama, Op. 4 BBC 07006 Chandos 9631 095115963128 Philharmonic/Bamert 02:15:1008:17 Curnow River City Suite River City Brass Band 07846 River City 198A 753598019823 02:24:2733:58 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Berlin 07743 EMI 00273 509995002732 Philharmonic/Rattle 3 02:59:55 34:19 Elgar Falstaff, A Symphonic Study in Scottish National 00988 Chandos 8431 n/a C minor, Op. 68 Orchestra/Gibson 03:35:1413:55 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My London 05047 Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Fatherland) Symphony/Dorati 03:50:09 08:48 Donizetti Ballet music from The Siege of Philharmonia/de 01826 Philips 422 844 028942284425 Calais Almeida 04:00:2706:53 Borodin Nocturne from String Quartet Salerno-Sonnenberg/K 04974 EMI 56481 724355648129 No. -

Vol. 13, No. 5 July 2004

Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promena Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembran Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Ga Salut d'Amour • Mot d'AmourElgar • Bizarrerie Society • O Happy Eyes • My Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenad Capricieuse • Serenadeournal • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda Snow • Fly, Singing Bird • From the Bavarian Highlands • The L Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George • Te and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Original T (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson de Matin • Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius • Serenade Ly Pomp and Circumstance • Cockaigne (In London Town) • C Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Chil Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduction and Allegro • Ev Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • How Calm Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concer minor • Romance • Symphony No 2 • O Hearken Thou • Coro March • Crown of India • Great is the Lord • Cantique • The Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Win • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Un dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • SonataJULY in E 2004minor Vol.13, • String No .5Quartet in E minor • Piano Quint minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wand E i M h Th H ld B B l