Thematic Environmental History Aboriginal History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Covenanting Congregations in Victoria

COVENANTING CONGREGATIONS IN VICTORIA In Victoria, covenanting covers a range of relationships – between congregations, between parishes and between clergy. Both metropolitan and country churches are involved. Some covenants are longstanding; others have been developed much more recently. The Trinity Declaration and Code of Practice between Anglican and Uniting Churches provides guidelines and ongoing support for cooperating congregations. Christ Church Kensington has been a joint Anglican-Uniting parish for twenty years. The members always worship together and there is no distinction between them. One of the tasks has been to keep the two traditions alive – hard work! There has been heartache, as being a joint congregation has not always been easy. However, the congregation values its ecumenical nature and its openness, flexibility and inclusiveness. Children especially value their place in the congregation. Besides membership from the two founding traditions, members have come from other traditions; there are several Catholics among the members. The increasing gentrification of Kensington has placed the congregation in communal change, but members value the opportunity to witness to the rest of the church. Until recently there have been two clergy, one from each tradition, but currently there is an Anglican priest. In Melbourne, one of the oldest covenants is that between three traditions at Toorak . In this suburb, St John’s Anglican, St Peter’s Catholic and Toorak Uniting churches are in the same street, in close proximity, encouraging a tightly knit community. The Toorak Ecumenical Covenant has been renewed annually at Pentecost for seventeen years. The congregations pray for each other at every service and together each month. -

An Environmental Profile of the Loddon Mallee Region

An Environmental Profile of the Loddon Mallee Region View from Mount Alexander looking East, May 1998. Interim Report March 1999 Loddon Mallee Regional Planning Branch CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………………………………………….. 1 2. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Part A Major Physical Features of the Region 3. GEOGRAPHY ………………………………………………………………………… 5 3.1 GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 3.1.1 Location ………………………………………………………………………………………... 5 3.1.2 Diversity of Landscape ……………………………………………………………………….…. 5 3.1.3 History of Non-Indigenous Settlement ……………………………………………………………. 5 3.2 TOPOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 3.2.1 Major Landforms ………………………………………………………………………..………. 6 3.2.1.1 Southern Mountainous Area …………………………………………………………….…………..…. 6 3.2.1.2 Hill Country …………………………………………………………………………………….…….………. 6 3.2.1.3 Riverine ………………………………………………………………………………………….……………. 6 3.2.1.4 Plains …………………………………………………………………………………………….….……….. 6 3.2.1.5 Mallee …………………………………………………………………………………………….….………. 7 3.3 GEOLOGY …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 3.3.1 Major Geological Features …………………………………………………………….………… 8 3.3.2 Earthquakes …………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 4. CLIMATE ……………………………………………………………………………… 11 4.1 RAINFALL …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….. 11 4.2 TEMPERATURE ……………………………………………………………………………….………. 12 4.2.1 Average Maximum and Minimum Temperatures …………………………………………….………… 12 4.2.1 Temperature Anomalies ………………………………………………………………….……… 13 4.2.3 Global Influences on Weather……………………………………………………………………. -

Town and Country Planning Board of Victoria

1965-66 VICTORIA TWENTIETH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING BOARD OF VICTORIA FOR THE PERIOD lsr JULY, 1964, TO 30rH JUNE, 1965 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 5 (2) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1961 [Appro:timate Cost of Report-Preparation, not given. Printing (225 copies), $736.00 By Authority A. C. BROOKS. GOVERNMENT PRINTER. MELBOURNE. No. 31.-[25 cents]-11377 /65. INDEX PAGE The Board s Regulations s Planning Schemes Examined by the Board 6 Hazelwood Joint Planning Scheme 7 City of Ringwood Planning Scheme 7 City of Maryborough Planning Scheme .. 8 Borough of Port Fairy Planning Scheme 8 Shire of Corio Planning Scheme-Lara Township Nos. 1 and 2 8 Shire of Sherbrooke Planning Scheme-Shire of Knox Planning Scheme 9 Eildon Reservoir .. 10 Eildon Reservoir Planning Scheme (Shire of Alexandra) 10 Eildon Reservoir Planning Scheme (Shire of Mansfield) 10 Eildon Sub-regional Planning Scheme, Extension A, 1963 11 Eppalock Planning Scheme 11 French Island Planning Scheme 12 Lake Bellfield Planning Scheme 13 Lake Buffalo Planning Scheme 13 Lake Glenmaggie Planning Scheme 14 Latrobe Valley Sub-regional Planning Scheme 1949, Extension A, 1964 15 Phillip Island Planning Scheme 15 Tower Hill Planning Scheme 16 Waratah Bay Planning Scheme 16 Planning Control for Victoria's Coastline 16 Lake Tyers to Cape Howe Coastal Planning Scheme 17 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Portland) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Belfast) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Warrnambool) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Heytesbury) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Otway) 18 Wonthaggi Coastal Planning Scheme (Borough of Wonthaggi) 18 Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme 19 Melbourne's Boulevards 20 Planning Control Around Victoria's Reservoirs 21 Uniform Building Regulations 21 INDEX-continued. -

Tovvn and COUN1'r,Y PL1\NNING 130ARD

1952 VICTORIA SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT 01<' THE TOvVN AND COUN1'R,Y PL1\NNING 130ARD FOI1 THE PERIOD lsr JULY, 1951, TO 30rH JUNE, 1~)52. PHESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 4 (3) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLA},"NING ACT 1944. Appro:rima.te Cost of Repo,-1.-Preparat!on-not given. PrintJng (\l50 copieti), £225 ]. !'!! Jtutlt.ortt!): W. M. HOUSTON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 5.-[2s. 3d.].-6989/52. INDEX Page The Act-Suggested Amendments .. 5 Regulations under the Act 8 Planning Schemes-General 8 Details of Planning Schemes in Course of Preparation 9 Latrobe Valley Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 12 Abattoirs 12 Gas and Fuel Corporation 13 Outfall Sewer 13 Railway Crossings 13 Shire of Narracan-- Moe-Newborough Planning Scheme 14 Y allourn North Planning Scheme 14 Shire of Morwell- Morwell Planning Scheme 14 Herne's Oak Planning Scheme 15 Yinnar Planning Scheme 15 Boolarra Planning Scheme 16 Shire of Traralgon- Traralgon Planning Scheme 16 Tyers Planning Scheme 16 Eildon Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 17 Gelliondale Sub-Regional Planning Schenu• 17 Club Terrace Planning Scheme 17 Geelong and Di~triet Town Planning Scheme 18 Portland and DiHtriet Planning Scheme 18 Wangaratta Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 19 Bendigo and District Joint Planning Scheme 19 City of Coburg Planning Scheme .. 20 City of Sandringham Planning Seheme 20 City of Moorabbin Planning Scheme~Seetion 1 20 City of Prahran Plaml'ing Seheme 20 City of Camberwell Planning Scheme 21 Shire of Broadml'adows Planning Scheme 21 Shire of Tungamah (Cobmm) Planning Scheme No. 2 21 Shire of W odonga Planning Scheme 22 City of Shepparton Planning t::lcheme 22 Shire of W arragul Planning Seh<>liH' 22 Shire of Numurkah- Numurkah Planning Scheme 23 Katunga. -

Victoria Begins

VICTORIA. ANNO QUADRAGESIMO QUINTO VICTORIA BEGINS. No. DCCII. An Act for the Reform of the Constitution. [Reserved 27th Jane 1881. Royal Assent proclaimed 28th November 1881.] HEREAS it is desirable to make provision for the effectual Preamble, W representation of the people in the Legislative Council : Be it therefore enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly of Victoria in this present Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows (that is to say) :— 1. This Act shall be called and may be cited as The Legislative short title and Council Act 1881, and shall commence and come into force on the day commencement on which the Governor shall signify that Her Majesty has been pleased to assent thereto and it is divided into parts as follows— PART L—Number of provinces and number and distribution of members, ss. 4-7. PART II.—Periodical elections and tenure of seats, ss. 8-10. PART III.—Qualifications &c. of members, ss. 11-17. PART IV.—Qualification of electors, ss. 18-26. PART V.—Rolls of ratepaying electors, ss. 27-31. PART VI.—Miscellaneous provisions, ss. 32-48. 2. The Acts mentioned in the First Schedule to this Act are Repeal of Acts in hereby repealed from and after the commencement of this Act to the First Schedule. extent specified in the third column of the said Schedule : Provided that— (1.) Any enactment or document referring to any Act hereby repealed shall be construed to refer to this Act or to the corresponding enactment in this Act. -

Mount Gambier Cemetery Aus Sa Cd-Rom G

STATE TITLE AUTHOR COUNTRY COUNTY GMD LOCATION CALL NUMBER "A SORROWFUL SPOT" - MOUNT GAMBIER CEMETERY AUS SA CD-ROM GENO 2 COMPUTER R 929.5.AUS.SA.MTGA "A SORROWFUL SPOT" PIONEER PARK 1854 - 1913: A SOUTHEE, CHRIS AUS SA BOOK BAY 7 SHELF 1 R 929.5.AUS.SA.MTGA HISTORY OF MOUNT GAMBIER'S FIRST TOWN CEMETERY "AT THE MOUNT" A PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF EARLY WYCHEPROOF & AUS VIC BOOK BAY 10 SHELF 3 R 994.59.WYCH.WYCH WYCHEPROOF DISTRICT HISTORICAL SOCIETY "BY THE HAND OF DEATH": INQUESTS HELD FOR KRANJC, ELAINE AND AUS VIC BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 4 R 614.1.AUS.VIC.GEE GEELONG & DISTRICT VOL 1 1837 - 1850 JENNINGS, PAM "BY THE HAND OF DEATH": INQUESTS HELD FOR KRANJC, ELAINE AND AUS VIC BOOK BAY 14 SHELF 2 614.1.AUS.VIC.GEE GEELONG & DISTRICT VOL.1 1837 - 1850 JENNINGS, PAM "HARMONY" INTO TASMANIAN 1829 & ORPHANAGE AUS TAS BOOK BAY 2 SHELF 2 R 362.732.AUS.TAS.HOB INFORMATION "LADY ABBERTON" 1849: DIARY OF GEORGE PARK PARK, GEORGE AUS ENG VIC BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 2 R 387.542.AUS.VIC "POPPA'S CRICKET TEAM OF COCKATOO VALLEY": A KURTZE, W. J. AUS VIC BOOK BAY 6 SHELF 2 R 929.29.KURT.KUR FACUTAL AND HUMOROUS TALE OF PIONEER LIFE ON THE LAND "RESUME" PASSENGER VESSEL "WANERA" AUS ALL BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 2 R 386.WAN "THE PATHS OF GLORY LEAD BUT TO THE GRAVE": TILBROOK, ERIC H. H. AUS SA BOOK BAY 7 SHELF 1 R 929.5.AUS.SA.CLA EARLY HISTORY OF THE CEMETERIES OF CLARE AND DISTRICT "WARROCK" CASTERTON 1843 NATIONAL TRUST OF AUS VIC BOOK BAY 16 SHELF 1 994.57.WARR VICTORIA "WHEN I WAS AT NED'S CORNER…": THE KIDMAN YEARS KING, CATHERINE ALL ALL BOOK BAY 10 SHELF 3 R 994.59.MILL.NED -

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria Showing the County, the Land District, and the Municipality in which each is situated. (extracted from Township and Parish Guide, Department of Crown Lands and Survey, 1955) Parish County Land District Municipality (Shire Unless Otherwise Stated) Acheron Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Addington Talbot Ballaarat Ballaarat Adjie Benambra Beechworth Upper Murray Adzar Villiers Hamilton Mount Rouse Aire Polwarth Geelong Otway Albacutya Karkarooc; Mallee Dimboola Weeah Alberton East Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alberton West Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alexandra Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Allambee East Buln Buln Melbourne Korumburra, Narracan, Woorayl Amherst Talbot St. Arnaud Talbot, Tullaroop Amphitheatre Gladstone; Ararat Lexton Kara Kara; Ripon Anakie Grant Geelong Corio Angahook Polwarth Geelong Corio Angora Dargo Omeo Omeo Annuello Karkarooc Mallee Swan Hill Annya Normanby Hamilton Portland Arapiles Lowan Horsham (P.M.) Arapiles Ararat Borung; Ararat Ararat (City); Ararat, Stawell Ripon Arcadia Moira Benalla Euroa, Goulburn, Shepparton Archdale Gladstone St. Arnaud Bet Bet Ardno Follett Hamilton Glenelg Ardonachie Normanby Hamilton Minhamite Areegra Borug Horsham (P.M.) Warracknabeal Argyle Grenville Ballaarat Grenville, Ripon Ascot Ripon; Ballaarat Ballaarat Talbot Ashens Borung Horsham Dunmunkle Audley Normanby Hamilton Dundas, Portland Avenel Anglesey; Seymour Goulburn, Seymour Delatite; Moira Avoca Gladstone; St. Arnaud Avoca Kara Kara Awonga Lowan Horsham Kowree Axedale Bendigo; Bendigo -

Indigo Shire Heritage Study Volume 1 Part 2 Strategy & Appendices

Front door, Olive Hills TK photograph 2000 INDIGO SHIRE HERITAGE STUDY VOLUME 1 PART 2 STRATEGY & APPENDICES PREPARED FOR THE INDIGO SHIRE COUNCIL PETER FREEMAN PTY LTD CONSERVATION ARCHITECTS & PLANNERS • CANBERRA CONSULTANT TEAM FINAL AUGUST 2000 INDIGO SHIRE HERITAGE STUDY CONTENTS VOLUME 1 PART 2 STRATEGY & APPENDICES 8.0 A HERITAGE STRATEGY FOR THE SHIRE 8.1 Heritage Conservation Objectives 190 8.2 A Heritage Strategy 190 8.3 The Nature of the Heritage Resources of the Shire 191 8.4 Planning and Management Context 194 8.5 Clause 22 Heritage Policies 196 8.6 Financial Support for Heritage Objectives 197 8.7 Fostering Community Support for Heritage Conservation 198 8.8 A Community Strategy 199 8.9 Implementing the Heritage Strategy 200 APPENDIX A Indigo Shire Heritage Study Brief APPENDIX B Select Bibliography APPENDIX C Historical photographs in major public collections APPENDIX D Glossary of mining terminology APPENDIX E Statutory Controls APPENDIX F Indigo Planning Scheme - Clause 43.01 APPENDIX C Economic Evaluation of the Government Heritage Restoration Program [Extract from report] APPENDIX H Planning Strategy and Policy - Heritage APPENDIX I Recommendations for inclusion within the RNE, the Heritage Victoria Register and the Indigo Shire Planning Scheme APPENDIX J Schedule of items not to be included in the Indigo Shire Planning Scheme APPENDIX K Inventory index by locality/number APPENDIX L Inventory index by site type i SECTION 8.0 A HERITAGE STRATEGY FOR THE SHIRE 8.1 Heritage Conservation Objectives 190 8.2 A Heritage Strategy -

Harashim 2010

Harashim The Quarterly Newsletter of the Australian & New Zealand Masonic Research Council ISSN 1328-2735 Issue 49 January 2010 First Prestonian Lecture in Australia John Wade at Discovery Lodge of Research Laurelbank Masonic Centre, in the inner Sydney suburbs, was the venue for the presentation of the first Prestonian Lecture in Australia by a current Prestonian Lecturer. Discovery Lodge of Research held a special meeting there on Wednesday 6 January to receive the Master of Quatuor Coronati Lodge No. 2076 EC, the editor of Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, and the Prestonian Lecturer for 2009—all in the person of Sheffield University’s Dr John Wade. Some 37 brethren attended the lodge, including the Grand Master, MWBro Dr Greg Levenston, and representatives from Newcastle and Canberra. WM Ewart Stronach introduced Bro Wade, outlining his academic and Masonic achievements, gave a brief account of the origin of Prestonian Lectures, and closed the lodge. Ladies and other visitors were then admitted, swelling the audience to 54, for a brilliant rendition of the lecture: ‘“Go and do thou likewise”, English Masonic Processions from the 18th to the 20th Centuries’. Bro Wade made good use of modern technology with a PowerPoint presentation, including early film footage of 20th-century processions, supplementing it with his own imitation of a fire-and-brimstone preacher, and a spirited rendition of the first verse of The Entered Apprentice’s Song. (continued on page 16) From left: GM Dr Greg Levenston, Tom Hall, WM Ewart Stronach, Ian Shanley, Dr John Wade, Malcolm Galloway, Dr Bob James, Tony Pope, Neil Morse, Andy Walker Issue 49 photo from John page Wade 1 About Harashim Harashim, Hebrew for Craftsmen, is a quarterly newsletter published by the Australian and New Zealand Masonic Research Council (10 Rose St, Waipawa 4210, New Zealand) in January, April, July and October each year. -

Community Profile Newstead 3462

Mount Alexander Shire Council Local Community Planning Project Community Profile Newstead 3462 Image by Leigh Kinrade 1 INTRODUCTION Mount Alexander Shire Council has been funded over three years until May 2014, through the State Government’s Department of Planning and Community Development, to undertake the Mount Alexander Shire Local Community Planning Project (LCPP). The project aims to support local community engagement across the Shire to enable communities to articulate their needs and aspirations through the development of local community-based Action Plans. In September 2011, Council announced that Newstead would be one of three townships to participate in the first round of planning. This document has been formulated to provide some background information about Newstead and a starting point for discussion. ABOUT MOUNT ALEXANDER SHIRE The original inhabitants of the Mount Alexander area were the Jaara Jaara Aboriginal people. European settlement dates from the late 1830s, with land used mainly for pastoral purposes, particularly sheep grazing. Population was minimal until the 1850s, spurred by gold mining from 1851, the construction of the railway line, and the establishment of several townships. Rapid growth took place into the late 1800s before declining as gold supplies waned and mines were closed. Relatively stable between the 1950’s and the 1980’s, the population increased from about 12,700 in 1981 to 16,600 in 2006. The 1 preliminary Estimated Resident Population for 2010 is 18,421 . Mount Alexander Shire (MAS, the Shire) forms part of the Loddon Mallee Region (the Region), which encompasses ten municipalities and covers nearly 59,000km 2 in size, or approximately 26 percent of the land area of the State of Victoria. -

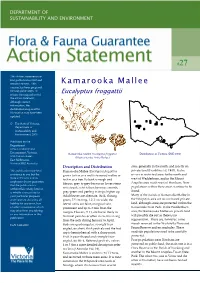

Kamarooka Mallee Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

#27 This Action Statement was first published in 1992 and remains current. This Kamarooka Mallee version has been prepared for web publication. It retains the original text of Eucalyptus froggattii the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. Kamarooka Mallee (Eucalyptus froggattii) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, (Illustration by Anita Barley) East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution sites, generally in the north, and mostly on This publication may be of Kamarooka Mallee (Eucalyptus froggattii) private land (Franklin et al. 1983). It also assistance to you but the grows to 6 m as a multi-stemmed mallee or occurs in restricted areas to the north and State of Victoria and its to 9 m as a tree. Its bark is rough and west of Wedderburn, and in the Mount employees do not guarantee fibrous, grey to grey-brown on lower stems Arapiles area south-west of Horsham. New that the publication is populations within these areas continue to be without flaw of any kind or or its trunk, which then becomes smooth, found. is wholly appropriate for grey-green and peeling in strips higher up. your particular purposes Adult leaves are alternate, thick, shining Many of the stands of Kamarooka Mallee in and therefore disclaims all green, 7.5 cm long, 1.2-2 cm wide; the the Whipstick area are on uncleared private liability for any error, loss lateral veins are faint, marginal vein land, although some are protected within the or other consequence which prominent and up to 3 mm from the Kamarooka State Park. -

WHITE HILLS and EAST BENDIGO HERITAGE STUDY 2016 Vol

WHITE HILLS AND EAST BENDIGO HERITAGE STUDY 2016 Vol. 2: Place and precinct citations Adopted by Council 15 November 2017 Prepared for City of Greater Bendigo WHITE HILLS AND EAST BENDIGO HERITAGE STUDY 2016 ii CITY OF GREATER BENDIGO Context Pty Ltd 2015 Project Team: Louise Honman, Director Ian Travers, Senior Heritage Consultant Catherine McLay, Heritage Consultant Jessie Briggs Report Register This report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled 1962 undertaken by Context Pty Ltd in accordance with our internal quality management system. Project Issue Notes/description Issue Issued to No. No. Date 1962 1 Draft citations 31/08/2015 Dannielle Orr 1962 2 Final draft citations 03/11/2015 Dannielle Orr 1962 3 Final citations 12/2/2016 Dannielle Orr 1962 4 Final citations 27/4/2016 Dannielle Orr 1962 5 Final citations adopted by City of 21/12/2017 Morgan James Greater Bendigo Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street, Brunswick VIC 3056 Phone 03 9380 6933 Facsimile 03 9380 4066 Email [email protected] Web www.contextpl.com.au 3 WHITE HILLS AND EAST BENDIGO HERITAGE STUDY 2016 4 CITY OF GREATER BENDIGO CONTENTS BRIDGE STREET NORTH PRECINCT 6 BULLER STREET PRECINCT 15 GLEESON STREET PRECINCT 22 NORFOLK STREET PRECINCT 29 WHITE HILLS PRECINCT 36 BAXTER STREET PRECINCT EXTENSION 45 TOMLINS STREET PRECINCT EXTENSION 53 8 BAKEWELL STREET, BENDIGO NORTH 60 105 BAXTER STREET, BENDIGO 63 80 NOLAN STREET, BENDIGO 66 POTTERS’ ARMS, 48-56 TAYLOR STREET, ASCOT 68 147 BARNARD STREET, BENDIGO 71 FORMER NORFOLK BREWERY, 3 BAYNE