Ibadan, Soutin and the Puzzle of Bower's Tower1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Vigilante in South-Western Nigeria Laurent Fourchard

A new name for an old practice: vigilante in South-western Nigeria Laurent Fourchard To cite this version: Laurent Fourchard. A new name for an old practice: vigilante in South-western Nigeria. Africa, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2008, 78 (1), pp.16-40. hal-00629061 HAL Id: hal-00629061 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00629061 Submitted on 5 Oct 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A new name for an old practice: vigilante in South-western Nigeria By Laurent Fourchard, Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, Centre d’Etude d’Afrique Noire, Bordeaux1 “We keep learning strange names such as vigilante for something traditional but vigilante has been long here. I told you, I did it when I was young”. Alhadji Alimi Buraimo Bello, 85 years, Ibadan, January 2003. Since the 1980s, the phenomenon of vigilante and vigilantism have been widely studied through an analysis of the rise of crime and insecurity, the involvement of local groups in political conflicts and in a more general framework of a possible decline of law enforcement state agencies. Despite the fact that vigilante and vigilantism have acquired a renewed interest especially in the African literature, Michael L. -

Speaking from the Middle Ground: Contexts and Intertexts

1 Speaking from the middle ground: contexts and intertexts In 1954 a graduate, one year out of college, was recruited to the Talks Department of the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS). By the age of twenty-eight, he was one of the most powerful media professionals in Nigeria. Before independence in 1960 he had established a second career as a fiction writer with the international publisher Heinemann – in due course, his first novel alone would sell an extraordinary ten million copies. Sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation, he celebrated his thirtieth birthday by embarking on an international tour that would help to establish him as one of the most influential voices in contemporary world literature. How should Chinua Achebe’s spectacular rise to prominence be understood? In Nigeria in the 1950s, the cultural field was undergoing profound, multidimensional change, as practices, values and assumptions previously taken for granted by producers and consumers in the media and the arts were rapidly redefined. With the systematic withdrawal of the British from public institutions, opportunities presented themselves to that first cohort of Nigerian graduates that must have seemed incred- ible to their parents’ generation. In this sense, from a historical point of view Achebe arrived on the scene at precisely the right moment. In broadcasting, the process of ‘Nigerianisation’ that preceded independence had produced an urgent demand for young, well-educated, home-grown talent, in exactly the form he exemplified. At the same time, in international publishing, decolonisation posed major challenges for big companies such Morrison_Achebe.indd 1 26/05/2014 12:03 2 Chinua Achebe as Longman and Oxford University Press. -

Olubadan's Unique Position in Yoruba Traditional History

ESV. Tomori M.A. THE UNIQUE POSITION OF OLUBADAN’S IN YORUBA TRADITIONAL HISTORY By: ESV. Tomori M.A. anivs, rsv, mnim Email: [email protected] Tel: 08037260502 Oluwo of Iwoland, Oba Abdulrasheed Akanbi in his interview with Femi Makinde on January 1, 2017, Sunday Punch, raised a lot of issues concerning Ibadan Chieftaincy System, settlements of Yoruba refugees within his domain in the nineteenth century and his family background which linked Iwo to the cradle, Ile-Ife. There are good reasons why we should seek to expand our understanding of the past, because each of us is a product of history. The more we understand our past that brought us to where we are today, the better we are likely to understand ourselves, who we are and where we are going History needs to be, as indeed it is, re-written from time to time and past events revalued in the light of fresh developments and new ideas. The facts of history are not settled by verbal insults or mere ego-tripping. Historical knowledge and enlightenment cannot translate to controversies, if the purpose is to seek and break new grounds over historical dogma and make-belief accounts. Every historical account, like other fields of knowledge must draw its premises and conclusion from sound logic. The Oluwo of Iwo, Oba Abdulrasheed Akanbi, should know that historical accounts all over the world have been noted to have an evolutionary trend when previously held beliefs, opinions and concepts are demolished under the weight of more factual, verifiable and attainable revelations by new frontiers of knowledge. -

Olubadan Centenary Anthology

1 Dedication This book is dedicated to His Royal Majesty Oba (Dr) Samuel Odulana, Odugade 1- An Icon of Peace and Justice All Rights Reserved © Ibadan Book Club - 2014 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication 2 Preface 5 Evolution in the unique system of selecting the Olubadan of Ibadan 6 Introduction 6 Ibadan‘s Unique System 7 Causative Factors of Longevity 9 Areas of Reform 11 A Bright Horizon Ahead 13 Origin of Ibadanland 14 Ibadan- A New Political Power in Yoruba Land 19 Olubadan 26 Ruling Lines 27 Accession Process 28 Today 28 List of Olubadan 29 Poems 35-41 Art Works 42-48 About Ibadan Book Club 48-51 4 PREFACE We thank God for the Gift of Long Life given to our Father, His Royal Majesty Oba (Dr) Samuel Odulana, Odugade 1. The memory of Baba will forever lingers in the memory of the sons and daughters of Ibadan land for his huge contributions and peaceful coexistence of Ibadan people. Ibadan is the citadel of literacy and literary art in Nigeria as it first accommodated the first literary Society ―Mbari Mayo‖ in Nigeria and the whole of Africa. We the members of the Society of Young Nigerian Writers and Ibadan Book Club congratulates our King, His Royal Majesty Oba (Dr) Samuel Odulana, Odugade 1 on his successful celebration of Baba‘s Centenary anniversary. We wish Baba more years ahead. Wole Adedoyin © 2014. 5 EVOLUTION IN THE UNIQUE SYSTEM OF SELECTING THE OLUBADAN OF IBADAN By Chief T.A. AKINYELE Introduction Each time an Olubadan is to be crowned many people who do not know the background history and the nature of the chieftaincy system in Ibadan have always wondered why Ibadan people choose to have very old men to lead them as their Oba and consequently almost every ten years a coronation ceremony occurs. -

Beyond Programmatic Versus Patrimonial Politics

Beyond programmatic versus patrimonial politics: contested conceptions of legitimate distribution in Nigeria LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/100250/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Roelofs, Portia (2019) Beyond programmatic versus patrimonial politics: contested conceptions of legitimate distribution in Nigeria. Journal of Modern African Studies, 57 (3). 415 - 436. ISSN 0022-278X https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X19000260 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ Beyond programmatic versus patrimonial politics: Contested conceptions of legitimate distribution in Nigeria PORTIA ROELOFS LSE Fellow, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE [email protected] Accepted for publication in Journal of Modern African Studies 12th March 2019. Forthcoming in 57:3 Autumn 2019. Abstract: This article argues against the long-standing instinct to read African politics in terms of programmatic versus patrimonial politics. Unlike the assumptions of much of the current quantitative literature, there are substantive political struggles that go beyond ‘public goods good, private goods bad’. Scholarly framings serve to obscure the essentially contested nature of what counts as legitimate distribution. This article uses the recent political history of the Lagos Model in southwest Nigeria to show that the idea of patrimonial versus programmatic politics does not stand outside of politics but is in itself a politically constructed distinction. -

Retailing a Forgettable Tale Akin

IVERYBODY WAS having a lunchrime drink in a bar in Kampala, Uganda one hot afternoon in November 1961. Then a 22-year-old man with a big head and lots of hah- entered, his arms saddled with copies of a new magazine he was trying to sell. As the hawker wended his way to a table, an angry Englishman bolted from the din of the afternoon, dashed in his way, snatched one of the magazines from him and ripped it in shreds. He couldn't have stopped at that. 'That's what I think of your trash!' he spat at the young man. In the Lugogo Retailing a Forgettable Akin Tale Adesokan Black Orpheus & Transition revisited Sports Club, another venue in taking his first shot at marketing, this reaction the city where the journal was was enough intimidation. ButRajatNeogy, the being peddled to members of a young man, was not an appretice hawker, not even an accomplished one. The journal he was jazz club, the manager vending, Transition was his brainchild, an threatened to eject the club for idea he had taken so seriously he staked his allowing what someone also personal convenience for it. He had returned called 'nasty left-wing to Uganda a year before, just married, with literature'. a degree in political science, with the intention For a prospective newspaper vendo of introducing his wife, a Swede, to his parents, African Quarterly on the Arts Vol.11 NO 5 take her round Kampala, then head for wanted from her was straightforward, journal and been impressed by its success. -

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide 1 Index The Mascot and the Ball ................................................................................................................ 3 Stadiums ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Is South Africa Ready? ................................................................................................................... 6 History ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Top Scorers .................................................................................................................................. 12 General Statistics ......................................................................................................................... 14 Groups ......................................................................................................................................... 16 South Africa ................................................................................................................................. 17 Angola ......................................................................................................................................... 22 Morocco ...................................................................................................................................... 28 Cape Verde ................................................................................................................................. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT DECEMBER 29, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. -

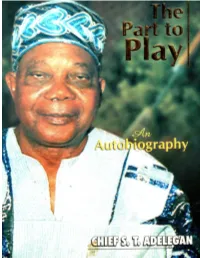

THE PART to PLAY an Autobiography

THE PART TO PLAY An Autobiography of Chief S. T. Adelegan Deputy-Speaker Western Region of Nigeria House of Assembly 1960-1965 The Story of the Life of a Nigerian Humanist, Patriot & Selfless Service i THE PART TO PLAY Author Shadrach Titus Adelegan Printing and Packaging Kingsmann Graffix Copyright: Terrific Investment & Consulting All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Author. Republished 2019 by: Terrific Investment & Consulting ISBN 30455-1-5 All enquiries to: [email protected], [email protected], ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dedication iv Foreword v Introduction vi Chapter One: ANTECEDENTS 1 Chapter Two: MY EARLY YEARS 31 Chapter Three: AT ST ANDREWS COLLEGE, OYO 45 Chapter Four THE UNFORGETABLE ENCOUNTER WITH OONI ADESOJI ADEREMI 62 Chapter Five DOUBLE PROMOTION AT THE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, IBADAN 73 Chapter Six NOW A GRADUATE TEACHER 86 Chapter Seven THE PRESSURE BY MY NATIVE COMMUNITY & MY DILEMMA 97 Chapter Eight THE COST OF PATRIOTISM & POLITICAL PERSECUTION 111 Chapter Nine: HOW WE BROKE THE MONOPOLY OF DR. NNAMDI AZIKIWE’S NCNC 136 Chapter Ten THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC 156 Chapter Eleven THE FINAL COLLAPSE OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC - 180 Chapter Twelve COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION MEETING 196 Chapter Thirteen POLITICAL RELATIONSHIP 209 Chapter Fourteen SERVICE WITHOUT REMUNERATION 229 Chapter Fifteen TRIBUTES 250 Chapter Sixteen GOING FORWARD 275 Chapter Seventeen ABOUT THE AUTHOR 280 iii DEDICATION To God Almighty who has used me as an ass To be ridden for His Glory To manifest in the lives of people; And Also, To Humanity iv FOREWORD Shadrach Titus Adelegan, one of Nigeria’s astute politicians of the First Republic, and an outstanding educationist and community leader is one of the few Nigerians who have contributed in great and concrete terms to the development of humanity. -

Textiles, Political Propaganda, and the Economic Implications in Southwestern Nigeria

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2012 Textiles, Political Propaganda, and the Economic Implications in Southwestern Nigeria Margaret Olugbemisola Areo Obafemi Awolowo University, [email protected] Adebowale Biodun Areo University of Lagos, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Olugbemisola Areo, Margaret and Biodun Areo, Adebowale, "Textiles, Political Propaganda, and the Economic Implications in Southwestern Nigeria" (2012). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 657. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/657 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Textiles, Political Propaganda, and the Economic Implications in Southwestern Nigeria Margaret Olugbemisola Areo [email protected] & Adebowale Biodun Areo [email protected], [email protected] The Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria are renowned for their vibrant cultural environment. Textile usage in its multifarious forms takes a significant aspect in the people’s culture; to protect from the elements, to cloth the dead before burial, to honour ancestors in Egungun masquerade manifestations of the world of the dead as well as status symbol for the living1, to dress a house of funeral as done by the Bunni, a Yoruba tribe near Rivers Niger and Benue confluence,2 to record history when used in specially designed commemorative cloth for an occasion, as a leveler of status and to express allegiance when used as “aso ebi”, and in recent times as a propaganda cloth by political parties. -

File Download

Fashioning the Modern African Poet Nathan Suhr-Sytsma, Emory University Book Title: Poetry, Print, and the Making of Postcolonial Literature Publisher: Cambridge University Press Publication Place: New York, NY Publication Date: 2017-07-31 Type of Work: Chapter | Final Publisher PDF Permanent URL: https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/s9wnq Final published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781316711422 Copyright information: This material has been published in Poetry, Print, and the Making of Postcolonial Literature by Nathan Suhr-Sytsma. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Nathan Suhr-Sytsma 2017. Accessed September 25, 2021 6:50 PM EDT chapter 3 Fashioning the Modern African Poet DEAD: Christopher Okigbo, circa 37, member of Mbari and Black Orpheus Committees, publisher, poet ; killed in battle at Akwebe in September 1967 on the Nsukka sector of the war in Nigeria fighting on the secessionist side ...1 So began the first issue of Black Orpheus to appear after the departure of its founding editor, Ulli Beier, from Nigeria. Half a year had passed since the start of the civil war between Biafran and federal Nigerian forces, and this brief notice bears signs of the time’s polarized politics. The editors, J. P. Clark and Abiola Irele, proceed to announce “the poem opening on the opposite page”–more accurately, the sequence of poems, Path of Thunder – as “the ‘last testament’ known of this truly Nigerian character,” reclaiming Christopher Okigbo from Biafra for Nigeria at the same time as they honor his writing.