The Value of the Yangzhou Storytelling of Rogue Pi Wu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Spiritual Climate

MISS XIAXIN WU (Orcid ID : 0000-0001-5130-4395) Article type : Original Article Relationship between burnout and intention to leave amongst clinical nurses: the role of spiritual climate A short informative title: Spirituality; Nursing practice; Evaluation; Relationship; job satisfaction; job burnout; turnover intention Article Short running title: Spiritual Climate plays a role in nurse performance List of all authors: Associate Prof Yu ZHANG, RN, PhD (first author, corresponding author) School of Nursing, Yangzhou University 136 Jiangyang Middle Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. Ph:(0514)+ 8687978842 Email: [email protected] This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/jonm.12810 Accepted This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Miss Xiaxin WU, RN, MSN(co-first author) School of Nursing, Yangzhou University 136 Jiangyang Middle Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. Email: [email protected] Ms Xiaojuan WAN, RN, MSN School of Nursing, Yangzhou University 136 Jiangyang Middle Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. Email: [email protected] Article Prof Mark Hayter Faculty of Health Science, University of Hull HU6 7RX, Hull, UK Email: [email protected] Miss Jinfeng WU, RN, MSN School of Nursing, Yangzhou University 136 Jiangyang Middle Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. Email: [email protected] Miss Shuang LI, Master School of Nursing, Yangzhou University. 136 Jiangyang Middle Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. -

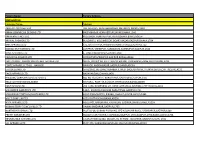

Produzent Adresse Land Allplast Bangladesh Ltd

Zeitraum - Produzenten mit einem Liefertermin zwischen 01.01.2020 und 31.12.2020 Produzent Adresse Land Allplast Bangladesh Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaliganj, Gazipur, Rfl Industrial Park Rip, Mulgaon, Sandanpara, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. (Unit - 3) Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh HKD International (Cepz) Ltd. Plot # 49-52, Sector # 8, Cepz, Chittagong Bangladesh Lhotse (Bd) Ltd. Plot No. 60 & 61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Plastoflex Doo Branilaca Grada Bb, Gračanica, Federacija Bosne I H Bosnia-Herz. ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Spueu Cambodia Powerjet Home Product (Cambodia) Co., Ltd. Manhattan (Svay Rieng) Special Economic Zone, National Road 1, Sangkat Bavet, Krong Bavet, Svaay Rieng Cambodia AJS Electronics Ltd. 1st Floor, No. 3 Road 4, Dawei, Xinqiao, Xinqiao Community, Xinqiao Street, Baoan District, Shenzhen, Guangdong China AP Group (China) Co., Ltd. Ap Industry Garden, Quetang East District, Jinjiang, Fujian China Ability Technology (Dong Guan) Co., Ltd. Songbai Road East, Huanan Industrial Area, Liaobu Town, Donggguan, Guangdong China Anhui Goldmen Industry & Trading Co., Ltd. A-14, Zongyang Industrial Park, Tongling, Anhui China Aold Electronic Ltd. Near The Dahou Viaduct, Tianxin Industrial District, Dahou Village, Xiegang Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Aurolite Electrical (Panyu Guangzhou) Ltd. Jinsheng Road No. 1, Jinhu Industrial Zone, Hualong, Panyu District, Guangzhou, Guangdong China Avita (Wujiang) Co., Ltd. No. 858, Jiaotong Road, Wujiang Economic Development Zone, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Bada Mechanical & Electrical Co., Ltd. No. 8 Yumeng Road, Ruian Economic Development Zone, Ruian, Zhejiang China Betec Group Ltd. -

New Lotoke Industry Group Co Limited

NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. 8, Jinrong Road, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China Phone:+86 514-85073387 Email:[email protected] NEW LOTOKE INDUSTRY GROUP CO LIMITED www.newlotoke.com Address:No. -

Can Higher Education, Economic Growth and Innovation Ability Improve Each Other?

sustainability Article Can Higher Education, Economic Growth and Innovation Ability Improve Each Other? Haiying Xu 1 , Wei-Ling Hsu 1,* , Teen-Hang Meen 2 and Ju Hua Zhu 3 1 School of Urban and Environmental Science, Huaiyin Normal University, Huai’an 223300, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Electronic Engineering, National Formosa University, Yunlin 632, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, Korea University, Seoul 02841, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 February 2020; Accepted: 22 March 2020; Published: 23 March 2020 Abstract: This study argues that the coupling between higher education, economic growth, and innovation ability is of great significance for regional sustainable development. Through the experience of Jiangsu Province in China, this study establishes a coupling coordination evaluation index system and applies the coupling coordination model to evaluate interactive relationships among the three. It finds that during 2007–2017, the level of coupling of 13 prefecture-level cities in Jiangsu was increasing over time, which fully verified the previous scholars’ view that the three can improve each other over a long period. However, this study finds that there are obvious differences within Jiangsu. Inadequate investment in higher education has become a crucial constraint on sustainable economic growth in northern and central Jiangsu, which are backward regions of Jiangsu. By contrast, in southern Jiangsu, which is the advanced region of Jiangsu, although the resources of higher education are abundant the growth of innovation ability cannot support sustained economic growth well. Thus, the quality of higher education should be improved to meet the needs of the innovation-based economy. -

Nanjing / Zhangjiagang/ Shanghai Barge--Nzb

Last Update Date: 22-Dec-2016 NANJING / ZHANGJIAGANG/ SHANGHAI BARGE--NZB Vessel Name DA XIN 1 Vessel Name DA XIN 66 Vessel Name DA XIN 6 Vessel Name DA XIN 1 Vessel/Voyage 01D / 236 Vessel/Voyage 17J / 009 Vessel/Voyage 34F / 135 Vessel/Voyage 01D / 237 Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Nanjing 23--23 Dec Nanjing --26 Dec Nanjing 28--29 Dec Nanjing 30--30 Dec Zhenjiang 24--24 Dec Zhangjiagang 27--27 Dec Zhenjiang 30--30 Dec Zhenjiang 31--31 Dec Zhangjiagang 24--24 Dec Nantong 27--27 Dec Yangzhou 30--30 Dec Zhangjiagang 31--31 Dec Nantong 24--25 Dec Shanghai 28--28 Dec Zhangjiagang 31--31 Dec Nantong 31--01 Jan Shanghai 25--26 Dec Shanghai 29-- Dec Shanghai 31--31 Dec Shanghai 01--02 Jan Shanghai 26--27 Dec Shanghai 01--01 Jan Shanghai 02--03 Jan Shanghai 27--27 Dec Shanghai 01--01 Jan Shanghai 03--03 Jan Nantong 28--28 Dec Zhangjiagang 02--02 Jan Nantong 04--04 Jan Zhangjiagang 29--29 Dec Yangzhou 03--03 Jan Zhangjiagang 05--05 Jan Nanjing 30--30 Dec Nanjing 04--05 Jan Nanjing 06--06 Jan Vessel Name DA XIN 6 Vessel Name DA XIN 1 Vessel Name DA XIN 6 Vessel Name DA XIN 1 Vessel/Voyage 34F / 136 Vessel/Voyage 01D / 238 Vessel/Voyage 34F / 137 Vessel/Voyage 01D / 239 Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Nanjing 04--05 Jan Nanjing 06--06 Jan Nanjing 11--12 Jan Nanjing 13--13 Jan Zhenjiang 06--06 Jan Zhenjiang 07--07 Jan Zhenjiang 13--13 Jan Zhenjiang 14--14 Jan Yangzhou 06--06 Jan Zhangjiagang 07--07 Jan Yangzhou 13--13 Jan Zhangjiagang 14--14 Jan Zhangjiagang 07--07 Jan Nantong 07--08 Jan Zhangjiagang -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

Yangzhou Guangling District Taihe Rural

Yangzhou Guangling District Taihe Rural Micro-finance Company Limited 揚州市廣陵區泰和農村小額貸款股份有限公司 (A joint stock limited liability company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China) (Stock code: 8252) REPLY SLIP FOR ATTENDANCE AT THE DOMESTIC SHAREHOLDERS CLASS MEETING TO BE HELD AT 2/F, NO. 1 HONGQI AVENUE, JIANGWANG STREET, HANJIANG DISTRICT, YANGZHOU CITY, JIANGSU PROVINCE, THE PRC ON WEDNESDAY, 6 MARCH 2019 AT 10:00 A.M. OR AT ANY ADJOURNMENT THEREOF To: Yangzhou Guangling District Taihe Rural Micro-finance Company Limited (the “Company”) I/We (Note 1) ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ , of (Note 1) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ , being the registered holder(s) of (Note 2) __________________________________________________ domestic share(s) of the Company, hereby inform the Company that I/We intend to attend (in person or by a proxy) the class meeting of the domestic shareholders of the Company to be held at 2/F, No. 1 Hongqi Avenue, Jiangwang Street, Hanjiang District, Yangzhou City, Jiangsu Province, the PRC, on Wednesday, 6 March 2019 at 10:00 a.m. (or as soon as the class meeting of the -

Certain Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Products from the People's Republic of China

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE International Trade Administration Washington, D.C. 20230 C-570-011 Investigation POI: 01/01112-12/31112 Public Document E&C, Office VII: JMN June 2, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO: Paul Piquado Assistant Secretary for Enforcement and Compliance FROM: Christian Marsh ~ Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations SUBJECT: Decision Memorandum for the Preliminary Affirmative Countervailing Duty Determination in the Countervailing Duty Investigation of Certain Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Products from the People's Republic of China I. SUMMARY The Department of Commerce (Department) preliminarily determines that countervailable subsidies are being provided to producers and exporters of certain crystalline silicon photovoltaic products (certain solar products, or subject merchandise) from the People's Republic of China (PRC), as provided in section 703(b)(l) of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (the Act). II. BACKGROUND A. Initiation and Case History On December 31,2013, SolarWorld Industries America, Inc. (SolarWorld, or Petitioner) filed a petition with the Department seeking the imposition of countervailing duties (CVDs) on certain solar products from the PRC. 1 Supplements to the petition and our consultations with the Government of China (GOC) are described in the Initiation Checklist? On Janua7 22,2014, the Department initiated a CVD investigation on certain solar products from the PRC. 1 See Letter from Petitioner, "Petition for the Imposition of Antidumping and Countervailing Duties: Certain Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Products from the People's Republic of China and Taiwan," (December 31, 20 13) (the petition). 2 See "Countervailing Duty Initiation Checklist: Certain Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Products from the People's Republic of China," (January 22, 2014). -

Yangzhou Profile

Located in the middle of Jiangsu province, the north shore of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, Yangzhou is one of the most vibrant and forward-looking cities in the economic circle of the Yangtze River delta. It boasts of land coverage of 6,634 square kilometers and a population of 4.6 million, including an urban area of 1,100 square kilometers with a population of 1.31 million. As a hub of culture, arts and commerce, Yangzhou has a rich history of 2,500 years. There were three golden times in the history of Yangzhou. It took shape in the Han Dynasty, thrived in the Tang Dynasty and reached its peak in the Qing Dynasty. Many statesmen, writers and artists chanted the beautiful scenery and fascinating culture of Yangzhou, leaving behind numerous poems and essays, many of which known to every household. As an economically dynamic, ecologically friendly and environmentally beautiful city, the remarkable progress achieved by Yangzhou in sustainable urbanization in the last 30 years earned her the UN Habitat Scroll of Honour Award in 2006. How to Get to Yangzhou From Beijing ◎By Flight (Air China): Beijing – Yangzhou Airport: CA1841 08:40 am -10:30 am Yangzhou Airport— Shangri-La Hotel (by shuttle to city center; or by taxi: 40 minutes, around 150 Yuan) Yangzhou – Beijing Airport: CA1842 11:30 am-1:10 pm 1 ◎By High Speed Train: Beijing South Station – Zhenjiang South Station From 7:00 to 17:32, five trains are available now. Duration: 4 hours 20 minutes Price: First Class: 788.5 Yuan Second Class: 568.5 Yuan Zhenjiang South Station – Yangzhou Shangri-La Hotel (30 minutes by car) From Shanghai ◎By High Speed Train: Shanghai (Hongqiao) Station– Zhenjiang (South) Station Trains are available all day from 5:56 to 20:45. -

Modern Christian Landscape in Nanjing, China: a Literature Review

sustainability Review Modern Christian Landscape in Nanjing, China: A Literature Review Cheng Fang 1 and Bo Yang 2,3,* 1 Department of Landscape Architecture, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing 210037, China; [email protected] 2 School of Architecture and Planning, Jilin Jianzhu University, Changchun 130118, China 3 School of Landscape Architecture and Planning, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-520-621-1009 Received: 26 September 2017; Accepted: 17 November 2017; Published: 22 November 2017 Abstract: Between the First Opium War in 1840 and the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the development of modern Christianity in Nanjing expanded beyond the parameters of faith and spirituality, while interacting closely with Nanjing’s city life and space across a wider spectrum, such that a unique religious and cultural landscape was produced. Through an extensive literature review of 115 articles identified on this topic, this paper analyzes the development of the space of Christian churches in Nanjing, and further documents the pattern of interactions between Nanjing’s development as a modern city and its religious cultural landscape. Moreover, drawing from the theoretical perspective of Sense of Place, the paper summarizes the characteristics of religious cultural landscape in the aspects of vision and structure, function and modernization, and memory and identity, and points out that the Christian landscape should also be conducted from the activation of material form, local functions and historical meanings to achieve sustainable development of Christian landscape. Finally, the paper offers planning and design strategies for the continued growth of Christian landscape in Nanjing. -

Background Information Cooperation Program Breda-Yangzhou & Achievement for Now Join Us in the Water Tech Demonstration in Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China

Background information Cooperation program Breda-Yangzhou & Achievement for now Join us in the Water Tech Demonstration in Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province, China Since 2007, the City of Breda together with Waterboard Brabantse Delta has been cooperating with Jiangsu Province on water-related subjects. The agreement on conducting a five-year water program with the City of Yangzhou indicates that the concrete mutual understanding has been built-up and the cooperation comes to a new phase with pragmatic projects. The Water Tech Demonstration is designed to fill in the gap and facilitate the process of the transition. Thus, we are calling for the joint forces of Dutch water tech companies who have ambitions to build up and grow the network in China together with Breda’s international water cooperation program. This information booklet is to provide an overview of the cooperation program between Breda and partner cities in China, and local knowledge for you to evaluate the business opportunities in China. INTRO Breda-Yangzhou: pragmatic cooperation on water starts from 2018 2007 2009 2017 2018 2019 Cooperation started Sister-city partnership Agreement of Five- Program plan Execution started with established Year Cooperation approved and Year a short list of Program signed plan 2019 decided cooperation topics. Breda-Yangzhou: three themes INTRO Innovation in Asset Climate management resilience wastewater Management of sewer Blue-green treatment New techniques to and stormwater system infrastructure design techniques optimize the treatment and material -

CHINA ( Jiangsu Province) T."~I~Aifl,,&Nnl~M;~·F:·~ECHN~LQGY•· J

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] 2 '1 soa Nanjing Forum '96 12-15 November 1996 CHINA ( Jiangsu Province) t."~i~aifl,,&Nnl~M;~·F:·~ECHN~LQGY•· J ..