Risk: Rockets, Rovers and Reaching for the Stars with Dr. Farah Alibay and Col

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forever Remembered

July 2015 Vol. 2 No. 7 National Aeronautics and Space Administration KENNEDY SPACE CENTER’S magazine FOREVER REMEMBERED Earth Solar Aeronautics Mars Technology Right ISS System & Research Now Beyond NASA’S National Aeronautics and Space Administration LAUNCH KENNEDY SPACE CENTER’S SCHEDULE SPACEPORT MAGAZINE Date: July 3, 12:55 a.m. EDT Mission: Progress 60P Cargo Craft CONTENTS Description: In early July, the Progress 60P resupply vehicle — 4 �������������������Solemn shuttle exhibit shares enduring lessons an automated, unpiloted version of the Soyuz spacecraft that is used to ����������������Flyby will provide best ever view of Pluto 10 bring supplies and fuel — launches 14 ����������������New Horizons spacecraft hones in on Pluto to the International Space Station. http://go.nasa.gov/1HUAYbO 24 ����������������Firing Room 4 used for RESOLVE mission simulation Date: July 22, 5:02 p.m. EDT 28 ����������������SpaceX, NASA will rebound from CRS-7 loss Mission: Expedition 44 Launch to 29 ����������������Backup docking adapter to replace lost IDA-1 the ISS Description: In late July, Kjell SHUN FUJIMURA 31 ����������������Thermal Protection System Facility keeping up Lindgren of NASA, Kimiya Yui of JAXA and Oleg Kononenko of am an education specialist in the Education Projects and 35 ����������������New crew access tower takes shape at Cape Roscosmos launch aboard a Soyuz I Youth Engagement Office. I work to inspire students to pursue science, technology, engineering, mathematics, or 36 ����������������Innovative thinking converts repair site into garden spacecraft from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan to the STEM, careers and with teachers to better integrate STEM 38 ����������������Proposals in for new class of launch services space station. -

1 Pour Recréer Les Liens…

Pour recréer les liens… avec les Anciennes et les Anciens 1846-1986 1986 - TEMPUS FUGIT ... C’est mon petit côté latin incrusté de vieux séminariste! Mais, qu’on le veuille ou non, le temps file et les temps changent. En mai 2001, nous produisions le premier Nouvel-AS, un journal destiné aux Anciens et Anciennes du Séminaire et de l’Académie. L’idée venait d’une rencontre des membres du conseil d’administration de la Fondation de l’Académie Antoine- Manseau qui cherchaient un moyen pour contacter les Anciens et les Anciennes de notre Alma Mater et les rejoindre dans les années à venir. Ce printemps-là, nous avons envoyé par la poste un peu plus de deux mille sept cents copies de notre journal. Pour nous, c’était un bon début. Depuis ce temps, nous avons publié deux NAS par année, un en mai et l’autre en décembre. Au cours des années suivantes, nous avons retracé de nouvelles adresses d’Anciens et d’Anciennes en plus d’ajouter à nos listes les noms des élèves des nouvelles promotions. Nous avons pris plaisir à écrire ce que vous avez vécu et parfois à vous le faire raconter. Et nous en profitions également pour parler du développement de l’Académie et des exploits de ses élèves. En décembre 2012, puisque les temps changent et que la technologie se développe à vitesse grand V, nous passions à une autre étape : plus de la moitié des Nouvel- AS est dorénavant envoyée par courriel. Et il en sera de plus en plus ainsi à chaque numéro subséquent. -

March 2021 Universe

Featured Stories This is the first image Perseverance sent back after touching down on Mars on Feb. 18, 2021. The view, from one of Perseverance's Hazard Cameras, is partially obscured by a dust cover. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech Perseverance Lands on Mars! By Taylor Hill It’s confirmed: Jezero Crater will be the proving ground for the Perseverance rover to further our search for ancient Martian life. After seven minutes screaming through the Martian atmosphere, the Perseverance rover and its helicopter stowaway Ingenuity touched down safely on Mars. Perseverance mission commentator and guidance, navigation, and controls operations Lead Swati Mohan made the call at 12:55 p.m.; "Touchdown confirmed, Perseverance safely on the surface of Mars, ready to begin seeking the signs of past life." The first image taken by the rover's engineering camera was beamed back a mere two minutes later, providing visual evidence that the rover was truly safe on Mars' rocky red soil. Universe | March 2021 | Page 1 At JPL, select members of the Mars 2020 team, JPL Director Mike Watkins, NASA Acting Administrator Steve Jurczyk, NASA Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate Thomas Zurbuchen, and NASA Science Mission Directorate’s Planetary Science Division Director Lori Glaze cheered upon touchdown from the socially-distanced Mission Support Area (MSA) in Building 230, while a majority of the Mars 2020 team and the Lab watched a livestream from their homes—a markedly different landing day experience compared to past missions due to Covid safety precautions. At the time of landing, more than 2,600 JPLers were watching the Zoom livestream, while more than 2.2 million members of the public from around the world watched the NASA.gov Youtube livestream of the landing. -

Le Journal - 6

Le JournAL - 6 Les animaux de compagnie Les dossiers du mois : La COVID-19 Les emplois étudiants Avril – mai 2021 Le JournAL – 6 1 Bla bla Par Michael Bouchard Bonjour chers lecteurs, Dans ce numéro, nous ajoutons une nouvelle rubrique : Autour du monde, qui se trouve à la page 17. Celle-ci vous présentera, pour les premiers numéros, quelques monuments historiques dans le monde. L’année prochaine, elle contiendra des lieux à visiter ou elle présentera un pays en particulier. Avec la pandémie, il peut être difficile pour certaines personnes seules de continuer à travailler et à vivre. Cependant, l’adoption d’un animal peut grandement collaborer à une meilleure qua- lité de vie. C’est ce que l’on appelle la zoothérapie. Le dossier du sujet de ce mois-ci, les animaux de compagnie, contient des arguments pour convaincre vos parents d’acheter un animal, la vie avec un animal ou une liste d’animaux inusités, entre autres. Bien que le numéro concerne da- vantage les animaux que l’on peut avoir à la maison, il y a plein d’autres animaux. Par exemple, le sujet de la rubrique Savais-tu ? est l’éléphant. Le 11 mars dernier, tout le Québec a célébré la Journée de commémoration Nationale en mé- moire des victimes de la COVID-19. Une entrevue avec un élève de l’école qui a contracté la COVID-19 se trouve d’ailleurs à la page 10. Gardez espoir, grâce à la campagne de vaccination et le respect des mesures sanitaires de base, la fin de la pandémie approche bientôt ! Sommaire Bla bla -------------------------------------------- 2 Trouver un emploi ---------------------------- -

2020 Mars Society Convention Schedule

2020 Mars Society Convention Schedule Thursday October 15th All Times PDT Morning Plenaries 9:00 AM Dr. Robert Zubrin, President, The Mars Society 9:30 AM Dr. Chris McKay, NASA Ames, Prerequisites to Human Activity on Mars 10:00 AM Dr. Carol Stoker, NASA Ames, Potential Habitats for Life on Mars 10:30 AM Dr. Michael Hecht, PI, MOXIE, Mars Perseverance 11:00 AM Dr. Abigail Fraeman, Deputy Project Scientist, Mars Curiosity 11:30 AM Dr. Mark Panning, Project Scientist & Co-Investigator, Mars InSight 12:00 PM Dr. Adrian Brown: Mars 2020 and Mars Sample Return 12:30 PM Dr. Anna Yusupova, IBMP Russia: confinement experiments Afternoon Sessions Tech A Tech B Settlement A Medical TA-1 Romanko et a:l TB-1 Gilbert: Nuclear Fuel SA-1 Bhuiyan: Mars City M-1 Kir: Medicine on Oasis Mars Project Cycle for Mars Design for 1,000,000 Mars after 2050 1:00 PM TA-2 Lee Roberts: SA-2 Haeupli- M-2 Gardiner: Towards TB-2 Nikitaev: Seeding Underwater Mars Meusburger: Mars Healthy Living on Mars in H2 in NTP Engines Habitats Science City a Time of CV19 on Earth 1:30 PM SA-3 Jus Ad Astra: TB-3 Tan, Rezende et al Human Rights as a M-3 Jobin: Martian Operations of a Power foundation for a Mars Bill Mental Health Station on Mars 2:00 PM of rights M-4 Lordos: Large Scale TA-4 Pelc, Suscicka et al; TB-4 Kumar, Sharma et SA-4 Mayes: Utopian Space Settlements: A Evolution of a Mars al: Power Generation for Colonies on Mars New Frontier for Space Colony Mars using CO2 2:30 PM Psychology M-5 Kommareddy and TA-5 Lebedev: TB-5 Kumar, Adlakha et SA-5 Calanchi: A cultural Rezende: -

The Perseverance Mission – Looking for Life on Mars ORGANIZER Venn Diagram You Will Be Practicing Making Notes Using a Venn Diagram

Science, Technology, and the Environment The Perseverance mission – Looking for Life on Mars ORGANIZER Venn Diagram You will be practicing making notes using a Venn diagram. Th is structure is helpful in comparing and contrasting two or more issues, topics, or points-of-view. It helps you examine similarities and diff erences so you can draw conclusions or create new ideas, perspectives, or opinions. You will use the article “Th e Perseverance Mission – Looking for Life on Mars” to compare and contrast the physical characteristics of Earth and Mars that support life. BEFORE READING • Record the topic and purpose for reading on the Venn diagram. Th en, list what you already know about the topic of the article, Looking for Life on Mars, in the left -hand column. In the right-hand column, write what you want to know or wonder about the topic. For example, What do NASA scientists hope to fi nd? Does this mission have astronauts on board? DURING READING • As you read the article be mindful of questions that arise. Mark the text with a ? each time a new question pops into your head. Write the question in the margin. For example, in the second paragraph you may wonder why it took almost eight months for Perseverance to reach Mars. • Also, make connections. Identify connections with the letters T-S (text-to-self), T-T (text-to-text), or T-W (text-to-world) and make brief notes in the margin to explain the connections. For example, in the second paragraph you and your family may have watched the video as Perseverance touched down on Mars (a text-to-self connection). -

NASA Advisory Council Meeting Minutes, July 2015

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL July 29-31, 2015 Jet Propulsion Laboratory Pasadena, California MEETING MINUTES ~~)?~ P. Diane Rausch ) Steven W. Squyres Executive Director Chair NASA Advisory Council Meeting July 29-31, 2015 NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL Jet Propulsion Laboratory Pasadena, California July 29-31, 2015 Public Meeting Minutes Table of Contents Call to Order, Announcements………………..…………………………………………………………………………………2 Opening Remarks by Council Chair……………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Welcome to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory………………………………..…………………………………………………….2 Remarks by NASA Administrator……………….…………………………………………........................................................3 NASA Space Flight Program and Management Requirements: NASA Procedural Requirements (NPR) 7120.5E Governance and the Role of Center Directors…………………………………………………………………………………...6 Institutional Committee Report……………….………………………………………………………………...……………….8 Joint Discussion on NRC Pathways to Exploration Report and NASA Human Exploration Strategy………………………..10 Human Exploration and Operations Committee Report……………………………………………………………………….13 Council Discussion………………....…………………………………………………………………......................................15 JPL Early Career Presentations……………………………………………….………………………………………………..16 Science Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………………………………..16 Aeronautics Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………………...................17 Council Discussion….………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18 Public Input…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….19 -

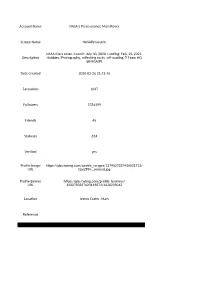

Comment Export List

Account Name NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover Screen Name NASAPersevere NASA Mars rover. Launch: July 30, 2020. Landing: Feb. 18, 2021. Description Hobbies: Photography, collecting rocks, off-roading. Team HQ @NASAJPL Date Created 2020-02-26 21:43:46 Favourites 1047 Followers 2784199 Friends 45 Statuses 624 Verified yes Profile Image https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/1379527227436531712/ URL QasZP9s-_normal.jpg Profile Banner https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_banners/ URL 1232783237623119872/1620235042 Location Jezero Crater, Mars Reference Source URL Export Date https://twitter.com/ 10.5.2021 NASAPersevere/ Reply count Total Before launch reply count Exposition 101 188 75 Cruise 93 162 Landing 6 41 Mission 49 134 First Tweet Comments 32 Nickname count "team" mention Count 35 Number of Comments on live 1199 tweet launch ID Name Username Retweets Comments 1 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 4729 437 2 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 217 31 3 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 233 68 4 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 3 2 5 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 3 1 6 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 3 2 7 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 184 29 8 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 317 44 9 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 1 10 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 5 1 11 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 1 1 12 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 3352 1436 13 NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover NASAPersevere 1 3 14 NASA's -

29Th AAS/AIAA Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, Ka’Anapali, Maui, Hawai’I

th 29 AAS/AIAA Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, January 13-17 Ka’anapali, HI AAS General Chair Dr. Matthew Wilkins L3 Advanced Defense Solutions AIAA General Chair Dr. Renato Zanetti The University of Texas at Austin AAS Technical Chair Dr. Francesco Topputo Images courtesy: John Hopkins APL Politecnico di Milano AIAA Technical Chair Dr. Andrew Sinclair Air Force Research Laboratory 1/6/2019 FINAL PROGRAM 29TH AAS/AIAA SPACE FLIGHT MECHANICS MEETING CONFERENCE INFORMATION GENERAL INFORMATION Welcome to the 29th Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, hosted by the American Astronautical Society (AAS) and co-hosted by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), January 13 – 17, 2018. This meeting is organized by the AAS Space Flight Mechanics Committee and the AIAA Astrodynamics Technical Committee, and held at the Sheraton Maui Resort and Spa, 2605 Ka’anapali, Maui, HI, (808)-661- 0031, https://www.marriott.com/hotels/travel/hnmsi-sheraton-maui-resort-and-spa/. REGISTRATION Registration Site ( https://www.xcdsystem.com/aas/attendee/index.cfm?ID=zP55GsC ) In order to encourage early registration, we have implemented the following conference registration rate structure: Register by November 30, 2018 and save $70! Category Early Registration Registration (beginning Walk-up Registration (through Nov 30, 2018) Dec 1, 2018) (beginning Jan 1, 2019) Full - AAS or AIAA $600 $670 $770 Member Full - Non-member $700 $770 $870 Retired or Student* - $250 $320 $420 Member Retired / Student* - Non- $300 / $295 $370 / $365 $470 / $465 member *does not include proceedings CD Refunds will be issued until December 31, 2018. A 10% fee will be assessed for all refunds issued after that date and until 8:00 am EST January 13, 2018. -

FARAH ALIBAY, PH., M.ENG., B.A. Ingé Nieure En Aérospatiale Animatrice, Conférenciè R E , Autrice

FARAH ALIBAY, PH., M.ENG., B.A. Ingé nieure en aérospatiale Animatrice, Conférenciè r e , Autrice UDA : N/A LANGUE(S) : FRANÇAIS, ANGLAIS (BILINGUE), ESPAGNOL (INTERMÉDIAIRE) YEUX : BRUNS CHEVEUX : NOIRS CONFÉRENCES ET FORMATIONS La persévérance d’une exploratrice Les beautés de la planète Mars EXPÉRIENCES PROFESSIONNELLES 2019- … Ingénieure système sénior, Mars 2021 Perseverance Rover Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California Support au niveau de la construction, des tests, et des opérations de l’astromobile Planification, implémentation et tests des activités de l’astromobile en soutien à la mission Ingenuity Tactical Integration Lead pour les opérations journalières sur Mars 2017- 2019 Ingénieure système des instruments, Insight Mars Lander Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California Membre de l’équipe en charge des instruments. Support aux tests et à la préparation des opérations avant le décollage de la mission en mai 2018. Soutien à l’équipe d’opérations à titre de tactical uplink shift lead. 2016–2017 Ingénieure système, Asteroid Redirect Robotic Mission (ARRM) Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California Planification de la mission ARRM, préparation du Plan de Mission en coordination avec une équipe d’ingénieurs distribuée à plusieurs sites de la NASA pour définir le concept de la mission et développer les besoins fonctionnels en utilisant Model Based Systems Engineering (MBSE). 2015-2016 Ingénieure système, SunRISE SMEX Mission of Opportunity Step 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California Développement d’une mission consistant d’un interféromètre qui observe les éjections de masse coronale dans le spectre radio en utilisant une constellation de petits satellites. Gestion de l’équipe technique et du fournisseur pour le vaisseau spatial, tout en travaillant avec l’équipe de scientifiques pour définir la mission.