2. Theory and Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

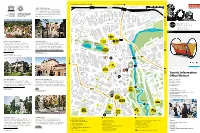

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922 Volume II Hilary Joyce Grainger Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. The University of Leeds Department of Fine Art January 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Notes to Chapters 1- 10 432 Bibliography 487 Catalogue of Executed Works 513 432 Notes to the Text Preface 1 Joseph William Gleeson-White, 'Revival of English Domestic Architecture III: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 147-58; 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture IV: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 27-33 and 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture V: The Work of Messrs George and Peto', The Studio, 1896 pp. 204-15. 2 Immediately after the dissolution of partnership with Harold Peto on 31 October 1892, George entered partnership with Alfred Yeates, and so at the time of Gleeson-White's articles, the partnership was only four years old. 3 Gleeson-White, 'The Revival of English Architecture III', op. cit., p. 147. 4 Ibid. 5 Sir ReginaldýBlomfield, Richard Norman Shaw, RA, Architect, 1831-1912: A Study (London, 1940). 6 Andrew Saint, Richard Norman Shaw (London, 1976). 7 Harold Faulkner, 'The Creator of 'Modern Queen Anne': The Architecture of Norman Shaw', Country Life, 15 March 1941 pp. 232-35, p. 232. 8 Saint, op. cit., p. 274. 9 Hermann Muthesius, Das Englische Haus (Berlin 1904-05), 3 vols. 10 Hermann Muthesius, Die Englische Bankunst Der Gerenwart (Leipzig. 1900). 11 Hermann Muthesius, The English House, edited by Dennis Sharp, translated by Janet Seligman London, 1979) p. -

Critical Values: the Career of Charles Rennie Mackintosh 1900-2015 Professor Pamela Robertson It Is a Great Pleasure to Be Back

Keynote Speech Strand 4 Critical Values: The Career of Charles Rennie Mackintosh 1900-2015 Professor Pamela Robertson It is a great pleasure to be back in Barcelona for this exciting Congress. I am grateful to the organisers, in particular Lluis Bosch and Mireia Freixa, for the invitation to speak to you today on Mackintosh, and to all those whose hard work has delivered such a successful and stimulating event. The strand this afternoon is research, specifically research in progress. This session invites us to reflect, for a moment, on critical values and critical fortunes. How are reputations and understandings formed? What value systems are they based on? How do they shift, and why? What are the future directions for us as curators, scholars, teachers? What I aim to present briefly today is threefold: an overview of the critical literature and research surrounding the career of Charles Rennie Mackintosh from around 1900 to 2015 (Fig. 1) – in the hope that this case study will provide some parallels with your individual experiences as researchers, whether working with male and/or female subjects; some reflections on the recently launched Mackintosh Architecture research website; and finally some general remarks on future directions for research. What emerges is the significance of context and individuals; the catalyst of curators and exhibitions; the gradual transference of Mackintosh's artistic legacy into the public domain; and, for Mackintosh at least, the central role of one institution, the University of Glasgow. In 1996, Alan Crawford divided Mackintosh's 'life after death' into three phases which comprised Mackintosh and the Architects, the Enthusiasts, and the Market.1 The trajectory of the scholarly presentation of Mackintosh’s work can, I believe, be divided into five broad phases, though of course at times these overlap: 1. -

A Symbol of Global Protec- 7 1 5 4 5 10 10 17 5 4 8 4 7 1 1213 6 JAPAN 3 14 1 6 16 CHINA 33 2 6 18 AF Tion for the Heritage of All Humankind

4 T rom the vast plains of the Serengeti to historic cities such T 7 ICELAND as Vienna, Lima and Kyoto; from the prehistoric rock art 1 5 on the Iberian Peninsula to the Statue of Liberty; from the 2 8 Kasbah of Algiers to the Imperial Palace in Beijing — all 5 2 of these places, as varied as they are, have one thing in common. FINLAND O 3 All are World Heritage sites of outstanding cultural or natural 3 T 15 6 SWEDEN 13 4 value to humanity and are worthy of protection for future 1 5 1 1 14 T 24 NORWAY 11 2 20 generations to know and enjoy. 2 RUSSIAN 23 NIO M O UN IM D 1 R I 3 4 T A FEDERATION A L T • P 7 • W L 1 O 17 A 2 I 5 ESTONIA 6 R D L D N 7 O 7 H E M R 4 I E 3 T IN AG O 18 E • IM 8 PATR Key LATVIA 6 United Nations World 1 Cultural property The designations employed and the presentation 1 T Educational, Scientific and Heritage of material on this map do not imply the expres- 12 Cultural Organization Convention 1 Natural property 28 T sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of 14 10 1 1 22 DENMARK 9 LITHUANIA Mixed property (cultural and natural) 7 3 N UNESCO and National Geographic Society con- G 1 A UNITED 2 2 Transnational property cerning the legal status of any country, territory, 2 6 5 1 30 X BELARUS 1 city or area or of its authorities, or concerning 1 Property currently inscribed on the KINGDOM 4 1 the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Arts and Crafts Movement: Exchanges Between Greece and Britain (1876-1930)

The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) M.Phil thesis Mary Greensted University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Contents Introduction 1 1. The Arts and Crafts Movement: from Britain to continental 11 Europe 2. Arts and Crafts travels to Greece 27 3 Byzantine architecture and two British Arts and Crafts 45 architects in Greece 4. Byzantine influence in the architectural and design work 69 of Barnsley and Schultz 5. Collections of Greek embroideries in England and their 102 impact on the British Arts and Crafts Movement 6. Craft workshops in Greece, 1880-1930 125 Conclusion 146 Bibliography 153 Acknowledgements 162 The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) Introduction As a museum curator I have been involved in research around the Arts and Crafts Movement for exhibitions and publications since 1976. I have become both aware of and interested in the links between the Movement and Greece and have relished the opportunity to research these in more depth. It has not been possible to undertake a complete survey of Arts and Crafts activity in Greece in this thesis due to both limitations of time and word constraints. -

16 Bauhaus and Beyond Friday, March 20, 2020 1:45 PM

16 Bauhaus and Beyond Friday, March 20, 2020 1:45 PM Admin Remember, any photograph or image you don't create must be given attribution in EVERY post you use it in. It's fine to use designs from elsewhere, as long as you give credit. Possible format for virtual Expo during exam time: First half hour, everybody in Pod A host a Zoom room, demonstrate what they have, answer questions from folks in Pods B,C,D, who stroll between Zoom rooms. Next half hour, Pod B is host, etc. Zooms are open, can still invite family and friends online. http://www.rchoetzlein.com/website/artmap/ Fiell, Charlotte & Peter. Design of the 20th Century. Taschen America, 2012. AesDes2020 Page 1 Fiell, Charlotte & Peter. Design of the 20th Century. Taschen America, 2012. Everything changed around 1920. Modernist era began. Abstract shapes, unadorned surfaces, function rules 1914-1918 WORLD WAR I Economies changed Art changed See timelines Short discussion: What do you already know about Bauhaus? Bauhaus video Design in a Nutshell, from the British Open University: http://www2.open.ac.uk/openlearn/design_nutshell/index.php# Brian Douglas Hayes. Bauhaus: A History and Its Legacy, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xYrzrqB0B8I. 8:38 Bauhaus has roots in Deutscher Werkbund Still trying to integrate craftsmanship with industrialization: 1907 -1935. Big change in aesthetics. The Deutscher Werkbund (German Association of Craftsmen) is a German association of artists, architects, designers, and industrialists, established in 1907. The Werkbund became an important element in the development of modern architecture and industrial design, particularly in the later creation of the Bauhaus school of design. -

The 1914 Werkbund Debate Resolved: the Design and Manufacture of Frank O

The 1914 Werkbund Debate Resolved: The Design and Manufacture of Frank O. Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao Irene Nero Concern about McDonaldization in architecture is not new pride should dictate that goods be of fine quality, so as not to to architectural discourse.1 The terms of expression may be “pollute the visual environment.”4 different, but some of the important issues are fundamentally Van de Velde, another of the founding members, was also the same as those found at the core of the historic 1914 influenced by England’s Industrial Revolution, but this time, Werkbund debate between Hermann Muthesius and Henry van by its vocal opponent—John Ruskin. Van de Velde was in de Velde. This landmark debate serves as one of the earliest, if agreement with Muthesius that goods produced should be of not the earliest, example of publicly demonstrated concern high quality, but felt that handcrafting in the English Arts among modern architects regarding the origins of design and and Crafts tradition was more appropriate for establishing a manufacture of architecture.2 Primarily, at debate was the is- national identity.5 Both of the powerful Werkbund members sue of architecture becoming a standardized type-object, sub- agreed that quality was an issue in the production of German ject to ubiquitous distribution, versus architecture remaining goods, but had divergent ideas regarding their manufacture. an individualized, artistically-inspired creation. “Sameness” Manufactured goods, however, were not the only items under was an issue, simply because it was deemed an affront to the consideration at the Werkbund exhibition for standardization. creative process. -

Shifts in Modernist Architects' Design Thinking

arts Article Function and Form: Shifts in Modernist Architects’ Design Thinking Atli Magnus Seelow Department of Architecture, Chalmers University of Technology, Sven Hultins Gata 6, 41296 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-72-968-88-85 Academic Editor: Marco Sosa Received: 22 August 2016; Accepted: 3 November 2016; Published: 9 January 2017 Abstract: Since the so-called “type-debate” at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne—on individual versus standardized types—the discussion about turning Function into Form has been an important topic in Architectural Theory. The aim of this article is to trace the historic shifts in the relationship between Function and Form: First, how Functional Thinking was turned into an Art Form; this orginates in the Werkbund concept of artistic refinement of industrial production. Second, how Functional Analysis was applied to design and production processes, focused on certain aspects, such as economic management or floor plan design. Third, how Architectural Function was used as a social or political argument; this is of particular interest during the interwar years. A comparison of theses different aspects of the relationship between Function and Form reveals that it has undergone fundamental shifts—from Art to Science and Politics—that are tied to historic developments. It is interesting to note that this happens in a short period of time in the first half of the 20th Century. Looking at these historic shifts not only sheds new light on the creative process in Modern Architecture, this may also serve as a stepstone towards a new rethinking of Function and Form. Keywords: Modern Architecture; functionalism; form; art; science; politics 1. -

The Bauhaus 1 / 70

GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 70 The Bauhaus 1 Art and Technology, A New Unity 3 2 The Bauhaus Workshops 13 3 Origins 26 4 Weimar 45 5 Dessau 57 6 Berlin 68 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS 2 / 70 © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT 3 / 70 1919–1933 Art and Technology, A New Unity A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © Kevin Woodland, 2020 Joost Schmidt, Exhibition Poster, 1923 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 4 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. MEGGS © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 5 / 70 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. MEGGS • The Arts & Crafts: Applied arts, craftsmanship, workshops, apprenticeship • Art Nouveau: Removal of ornament, application of form • Futurism: Typographic freedom • Dadaism: Wit, spontaneity, theoretical exploration • Constructivism: Design for the greater good • De Stijl: Reduction, simplification, refinement © Kevin Woodland, 2020 GRAPHIC DESIGN HISTORY / THE BAUHAUS / Art and TechnoLogy, A New Unity 6 / 70 1919–1933 -

Considering Peter Behrens

Engramma • temi di ricerca • indici • archivio • libreria • colophon 81 giugno 2010 ISBN:978-88-98260-26-3 Considering Peter Behrens Interviews with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (Chicago, 1961) and Walter Gropius (Cambridge, MA, 1964) Stanford Anderson As a young scholar I had the opportunity to interview both Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius about their experiences, as young men, in the atelier of Peter Behrens in Berlin. On June 27, 1961, when I had newly declared my doctoral dissertation project to be the work of Behrens, Mies received me for an hour in his office at 230 East Ohio Street in Chicago. On 6 February 1964, after my return from doctoral research in Europe and the beginning of my career at MIT, Walter Gropius entertained me for a two-hour lunch at his favorite restaurant in Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts.The interviews were not recorded, but I did immediately write out my record of the discussions. Information from these interviews appears in my 1968 dissertation, much later published as Peter Behrens and a New Architecture for the Twentieth Century (Anderson 2000). The dissertation did not provide the opportunity to consider the whole of the interviews or entertain their content. Here, for the most part I will give an account of the interviews, though I will quote some parts of my notes where they best convey the thoughts of either Mies or Gropius in the interviews. Both Mies and Gropius offered views of Behrens’ career before the time they converged in Berlin (1907-08), thus providing an apt entry point into the interviews. -

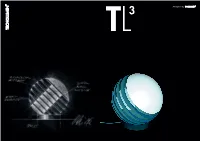

TL a Magazine By

A magazine by 3 TL Floor lamp BULO XL/BLON 16 P The new times give rise to a funda- up with fresh thoughts and new Well-conceived, clever and always mental question: How can I feel safe ideas. Pleasing tactile effects resul- functional: Oliver Niewiadomski and at ease? In future, we'll be ting from an excellent choice of translates a mathematical concept demanding a lot more of our homes. materials help to keep you grounded into incisive design language, as This refers to far more than just cosy in a digitised world. Old favourites here with the floor lamp BULO XL trends such as cocooning or hygge. give people something reliable and which sits neatly on its base to work It’s more a case of needing our own unchanging to hold on to. perfectly in any specific setting. intimate space of peace and quiet TECNOLUMEN has always combined where we can withdraw from the these essential factors, producing world and recharge our batteries in classic lamps “made in Germany” a feel-good atmosphere. This is using the best craftsmanship traditi- particularly challenging for those who ons and working together with small setting up a home office environ- companies who give outstanding ment in their own four walls, with a quality the same priority that we do. special need for feel-good spaces Let’s make the best of it! in between. The whole interior design industry is tackling the issues invol- ved and their various manifestations to cover all bases, taking an inspiring people-focused approach. Your Carsten Hotzan Good light is an essential factor to Executive Director of give rooms their desired effect. -

THE BAUHAUS / Overview I / Lxxii

GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / THE BAUHAUS / OVerVIew I / lXXII The Bauhaus 1 The Bauhaus 1 2 German workshops 5 3 The Weimar Location 23 4 The Dessau Location 44 5 New Faculty 53 6 The Epoch Closes 66 7 Conclusion 70 © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / THE BAUHAUS / OVerVIew II / lXXII © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / THE BAUHAUS 1 / 72 The Bauhaus 1919–1933 A German design school where ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine production. © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 JOOST SCHMIDT, EXHIBITION POSTER, 1923 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / THE BAUHAUS / The Bauhaus 2 / 72 The Bauhaus The name translated into The House of Construction or School of Building. • Weimar • Dessau • Berlin 1919–1925 1925–1932 1932–1933 1919 1920 1921 1922 1923 1924 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 Weimar Dessau Berlin Walter Gropius Hannes Meyer Ludwig Mies van der Rohe © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / THE BAUHAUS / The Bauhaus 3 / 72 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Twentieth-century furniture, architecture, product design, and graphics were shaped by the work of its faculty and students, and a modern design aesthetic emerged. – MEGGS © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / THE BAUHAUS / The Bauhaus 4 / 72 1919–1933 The Bauhaus Ideas from all advanced art and design movements were explored, combined, and applied to the problems of functional design and machine