Towards Single Embryo Transfer?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducion to Duplicate

INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE INTRODUCTION TO DUPLICATE BRIDGE This book is not about how to bid, declare or defend a hand of bridge. It assumes you know how to do that or are learning how to do those things elsewhere. It is your guide to playing Duplicate Bridge, which is how organized, competitive bridge is played all over the World. It explains all the Laws of Duplicate and the process of entering into Club games or Tournaments, the Convention Card, the protocols and rules of player conduct; the paraphernalia and terminology of duplicate. In short, it’s about the context in which duplicate bridge is played. To become an accomplished duplicate player, you will need to know everything in this book. But you can start playing duplicate immediately after you read Chapter I and skim through the other Chapters. © ACBL Unit 533, Palm Springs, Ca © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 1 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE This book belongs to Phone Email I joined the ACBL on ____/____ /____ by going to www.ACBL.com and signing up. My ACBL number is __________________ © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 2 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE Not a word of this book is about how to bid, play or defend a bridge hand. It assumes you have some bridge skills and an interest in enlarging your bridge experience by joining the world of organized bridge competition. It’s called Duplicate Bridge. It’s the difference between a casual Saturday morning round of golf or set of tennis and playing in your Club or State championships. As in golf or tennis, your skills will be tested in competition with others more or less skilled than you; this book is about the settings in which duplicate happens. -

Kibitzerkibitzer December, 2007

Palo Alto Unit 503 Volume XLV, Issue 12 KibitzerKibitzer December, 2007 Bridge, Dinner, and a Toy UNIT INFORMATION MISUSED SUNDAY, DECEMBER 9 Recently some of our members’ personal information provided by the ACBL was used to solicit them for com- Celebrate the Season by grabbing your favorite part- mercial purposes. The Unit respects our members' privacy and wants our members to know that the Unit as well as ner, finding a toy, and signing up to play free bridge and the ACBL does not permit this and that we are taking ac- eat a free dinner catered by Chef Chu on Sunday, Decem- tion to prevent this from recurring. ber 9th at your friendly Bridge Center. Your only pay- ment is in the form of an unwrapped new toy. The Unit has a new charity “Toys for Kids,” a local program for GIFTS GALORE needy kids in the Palo Alto area. They are looking for toys and games for children from pre-school to around GREET STAC PLAYERS sixth grade. Gift certificates for food (especially fast food) are popular with the older children. Partnerships should sign up before December 3. The Talk about the holiday spirit! Your friendly local Unit regrets that there is room for only 70 partnerships; club will award presents of extra masterpoints to those both must be Unit members. There will be two flights, an who excel in the STAC (Sectional Tournament at Clubs) open and a 99er. After the December 3 deadline the Tour- games during the week of Monday, December 17 through nament Chair, Martie Moore, will review the sign-up list Sunday, December 23. -

Gateway to the West Regional Sunday

Sunday July 14-19 Hi 92°F Low 75°F Daily Bulletin Gateway to the West Regional All St. Louis Regional Results: for coming to St. Louis and we’d like www.acbl.org & www.unit143.org, to see you right back here again next Unit 143 includes links to the week’s Daily Bulletins. year. We appreciate that you chose to attend our Regional ’coz we do it all for you! to our Caddies, We appreciate your fine work this week! Jackson Florea Anna Garcia Jenna Percich Lauren Percich Clara Riggio Frank Riggio Katie Seibert Kate Vontz Our Date Back to August 15-21, 2016 Come back and join us next August. Please put us on your Regional tournament calendar today. Charity Pairs Series Raises $ BackStoppers will receive the $$$$ that you helped us raise in the Saturday morning Charity Open Pairs Game and will be added to what Last Chance for Registration Gift & was raised in the Wednesday evening Swiss event. We support this To Pick Up Your Section Top Awards organization to express our appreciation for lives given on behalf of Sunday, from 10:00 – 10:20 AM before the Swiss Team session others. Unit 143 will present the check at their October Sectional. begins, and 30 minutes after the sessions end, will be the last opportunity to pick up your convention card holder and section Thanks for playing in these events and showing your support! top awards. Daily Grin How can you tell if someone is a lousy bridge player? No Peeking, Lew! He has 5 smiling Kibitzers watching him play. -

This Month's Newsletter Includes the Sections Listed Below. Click a Link to Jump to the Corresponding Section

This month's newsletter includes the sections listed below. Click a link to jump to the corresponding section. If your browser does not support these links, scroll down to find a specific section. ♦ President's Message ♦ Board Business ♦ New Members and Rank Advancements ♦ Unit News ♦ Club News ♦ From the Editors Please visit the Unit 174 Website (www.acblunit174.org) to view updated information about the activities in our Unit and at our Clubs. Wow – The 2019 Lone Star Regional is in the books – what a great week of bridge it was!!! I hope everyone had an enjoyable experience and played bridge to their heart's content. Personally, it was hectic, busy, and, looking back, fun and rewarding. It was good to see everyone from all over our Unit and District. Thank you to all who came and played! I would like to thank many people for all their efforts leading up to and during the week. My first thank you is to Lauri Laufman for her tireless work in planning, creating the schedule, working with the Marriott staff, updating the Daily Bulletin and being a sounding board and outstanding bridge partner! Lauri worked very hard to ensure this LSR was the best ever and I thank her for all her efforts. My thanks to the Unit Board – you all are supportive and willing to do whatever it takes to make sure the needs of the players are met. I would also like to thank our Chairpersons of the Hospitality, I/N and Newcomers and Partnership desks – Sam Khayatt, Nancy Guthrie and Bill and Nancy Riley. -

C:\My Documents\Adobe

American Contract Bridge League Presents Beached in Long Beach Appeals at the 2003 Summer NABC Plus cases from the 2003 Open and Women’s USBC Edited by Rich Colker ACBL Appeals Administrator Assistant Editor Linda Trent ACBL Appeals Manager CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................... iii The Expert Panel ................................................ v Cases from Long Beach Tempo (Cases 1-11) .......................................... 1 Unauthorized Information (Cases 12-20) ......................... 38 Misinformation (Cases 19-31).................................. 60 Other (Cases 32-37) ........................................ 107 Cases from U.S. Open and Women’s Bridge Championships (Cases 38-40) . 122 Closing Remarks From the Expert Panelists ......................... 138 Closing Remarks From the Editor ................................. 141 Advice for Advancing Players.................................... 143 NABC Appeals Committee ...................................... 144 Abbreviations used in this casebook: AI Authorized Information AWMW Appeal Without Merit Warning BIT Break in Tempo CoC Conditions of Contest CC Convention Card LA Logical Alternative MP Masterpoints MI Misinformation PP Procedural Penalty UI Unauthorized Information i ii FOREWORD We continue our presentation of appeals from NABC tournaments. As always our goal is to inform, provide constructive criticism and stimulate change (that is hopefully for the better) in a way that is instructive and entertaining. At NABCs, appeals from non-NABC+ -

Friendly Bridge Book, January 2020 Edition

Beginning Bridge Lessons By Ed Kinlaw and Linda MacCleave Richmond Bridge Association Richmond, Virginia Copyright © 2003 First printing September 2003 Revised second printing February 2004 Revised third printing May 2004 Revised fourth printing September 2004 Revised fifth printing February 2005 Revised sixth printing September 2005 Revised seventh printing February 2006 Revised eighth printing August 2006 Revised ninth printing March 2007 Tenth printing September 2007 Revised eleventh printing January 2008 Revised twelfth printing August 2008 Revised thirteenth printing February 2009 Fourteenth printing July 2009 Revised fifteenth printing February 2010 Sixteenth printing August 2010 Revised seventeenth printing January 2011 Revised eighteenth printing August 2011 Revised nineteenth printing March 2012 Revised twentieth printing April 2012 Twenty-first printing August 2012 Revised Twenty-fifth printing January 2014 Revised 26th printing August 2014 Revised 27th printing February 2015 28th printing August 2015 29th printing February 2016 30th printing July 2016 31st printing January 2017 32nd printing September 2017 33rd printing February 2018 34th printing August 2018 35th printing February 2019 36th printing August 2019 37th revised printing February 2020 2 Table of Contents Lesson 1: Mechanics of a Hand in Duplicate Bridge 5 Lesson 2: How to Open and How to Respond to One-level Suit 12 Lesson 3: Rebids by Opening Bidder and Responder 17 Lesson 4: Overcalls 24 Lesson 5: Takeout Doubles 27 Lesson 6: Responding to No-Trump Opening—Stayman -

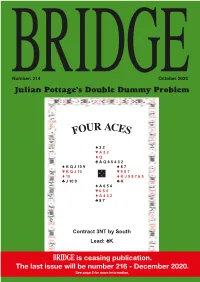

FOUR ACES Could Have Done More Safely

Number: 214 October 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem UR ACE FO S ♠ 3 2 ♥ A 3 2 ♦ Q ♣ A Q 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ K Q J 10 9 ♠ 8 7 ♥ N ♥ K Q J 10 W E 9 8 7 ♦ 10 S ♦ K J 9 8 7 6 5 ♣ J 10 9 ♣ K ♠ A 6 5 4 ♥ 6 5 4 ♦ A 4 3 2 ♣ 8 7 Contract 3NT by South Lead: ♠K BRIDGE is ceasing publication. The last issueThe will answer be will benumber published on page 216 4 next - month.December 2020. See page 5 for more information. A Sally Brock Looks At Your Slam Bidding Sally’s Slam Clinic Where did we go wrong? Slam of the month Another regular contributor to these Playing standard Acol, South would This month’s hand was sent in by pages, Alex Mathers, sent in the open 2♣, but whatever system was Roger Harris who played it with his following deal which he bid with played it is likely that he would then partner Alan Patel at the Stratford- his partner playing their version of rebid 2NT showing 23-24 points. It is upon-Avon online bridge club. Benjaminised Acol: normal to play the same system after 2♣/2♦ – negative – 2NT as over an opening 2NT, so I was surprised North Dealer South. Game All. Dealer West. Game All. did not use Stayman. In my view the ♠ A 9 4 ♠ J 9 8 correct Acol sequence is: ♥ K 7 6 ♥ A J 10 6 ♦ 2 ♦ K J 7 2 West North East South ♣ A 9 7 6 4 2 ♣ 8 6 Pass Pass Pass 2♣ ♠ Q 10 8 6 3 ♠ J 7 N ♠ Q 4 3 ♠ 10 7 5 2 Pass 2♦ Pass 2NT ♥ Q 9 ♥ 10 8 5 4 2 W E ♥ 7 4 3 N ♥ 9 8 5 2 Pass 3♣ Pass 3♦ ♦ Q J 10 9 5 ♦ K 8 7 3 S W E ♦ 8 5 4 ♦ Q 9 3 Pass 6NT All Pass ♣ 8 ♣ Q 5 S ♣ Q 10 9 4 ♣ J 5 Once South has shown 23 HCP or so, ♠ K 5 2 ♠ A K 6 North knows the values are there for ♥ A J 3 ♥ K Q slam. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

The Edwardia

Number: 211 July 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem E EDWARDIA T H N ♠ 8 5 3 ♥ Q 9 5 4 3 2 ♦ 2 ♣ A K 2 ♠ A 6 4 ♠ Void ♥ N ♥ 6 W E 10 8 7 ♦ A Q 10 8 S ♦ K J 9 7 5 ♣ 7 6 5 4 3 ♣ Q J 10 9 8 ♠ K Q J 10 9 7 2 ♥ A K J ♦ 6 4 3 ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥6 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. BERNARD MAGEE’S TUTORIAL CD-ROMs ACOL BIDDING ADVANCED DEFENCE l Opening Bids and ACOL BIDDING l Lead vs No-trump Responses l Basics Contracts l Slams and Strong l Advanced Basics l Lead vs Suit Contracts Openings l Weak Twos l Partner of Leader vs l £96 Support for Partner l Strong Hands No-trump Contracts l Pre-empting l Defence to Weak Twos l Partner of Leader vs l Suit Contracts Overcalls £66 l Defence to 1NT l l Count Signals No-trump Openings l Doubles £76 and Responses l Attitude Signals l Two-suited Overcalls l Opener’s and l Discarding Responder’s Rebids l Defences to Other Systems l Defensive Plan l Minors and Misfits l Misfits and l Stopping Declarer l Doubles Distributional Hands l Counting the Hand l Competitive Auctions Operating system requirements: Operating system requirements: Operating system requirements: Windows or Mac OS 10.08 -10.14 Windows only Windows or Mac OS 10.08 -10.14 DECLARER PLAY ADVANCED FIVE-CARD MAJORS l Suit Establishment in DECLARER PLAY & Strong No-Trump No-trumps l Overtricks in l Opening Bids & l Suit Establishment No-trumps £81 Responses in Suits l Overtricks in l No-Trump Openings l Hold-ups Suit Contracts l -

Two Major Upsets in Spingold KO Showdown Time in Wagar Teams

July 8-18, 2004 76th Summer North American Bridge Championships DAILY BULLETIN New York, New York Volume 76, Number 6 Wednesday, July 14, 2004 Editors: Brent Manley and Henry Francis Two major upsets in Spingold KO Teams captained by Rose Meltzer and Rita Shugart are on the sidelines today as the third round of play gets underway in the Spingold Knockout Teams. Meltzer’s all-star squad – Kyle Larsen, Peter Weichsel, Alan Sontag, Chip Martel and Lew Stansby – fell to the No. 61 seed, an all-England team captained by Jack Mizel. Meltzer jumped out to a 48-13 lead after the first quarter but were blasted 52-5 in the second quarter and never recovered as they dropped a 135-88 decision. Mizel played with Alexander Allfrey, Arthur Malinowsky and Andrew McIntosh. By contrast to the other match, Shugart held a 41-IMP lead with a quarter to go but were Welland tries harder, outscored 53-8 by a New York-Canada team led by Fred Hoffer. The final score was 140-136. but he’s not No. 2 Hoffer, of Cote Saint-Luc in Quebec, and As a games player from an early age, Roy fellow Canadian Don Piafsky of Toronto were Welland has always set high standards for himself. playing with New Yorkers Barry Piafsky, Allen “I’m a bit of a perfectionist,” says the 41-year- Kahn and David Rosenberg. old New Yorker. “If I do something, I try to do it as In another upset, the No. 15 seed, captained by The time has come well as humanly possible.” Bart Bramley, lost a close match to the team led by For Welland the bridge player, “as well as for Intellympics Phillip Becker. -

Graduation Exercises

SEVENTY-NINTH ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT GRADUATION EXERCISES MoNDAY, JuNE SEVENTH MCMXLVIII MEN's GYMNASIUM OREGON STATE COLLEGE PROGRAM Prelude Overture Militaire Skornika Processional University Grand March Edwin F. Goldman The College R.O.T.C. Band Delbert Warren Moore, Conductor The audience will remain seated throughout the processional but will rise when the Colors enter the auditorium and will remain standing until after the playing of the National Anthem. The National Anthem Invocation-THE REVEREND RoBERT DEGROFF BuLKLEY, Ph.B., B.D. Minister of the Federated Churches of Corvallis Tenor Solo-Ah! Tis the Day . R. Leoncavallo William Miller Iris Gray, Accompanist Greetings from the State Board of Higher Education GEORGE F. CHAMBERS, B.S. Member of the Oregon State Board of Higher Education Cortege Flor Peeters Joseph Brye, Organist The Wurlitzer electric organ, which is being used for the first time during this Seventy. ninth Annual Commencement, is largely a gift by the Class of 1948. See statement under GI FTS section of this program. Conferring of Degrees PRESIDENT AUGUST LEROY STRAND, Ph.D. Morning: Baccalaureate degrees for schools of Science, Agriculture, Busi ness and Technology, and Education; advanced degrees for candidates A to J inclusive. Afternoon : Baccalaureate degrees for schools of Engineering, Forestry, Home Economics, Pharmacy, and Nursing Education; advanced de grees for candidates K to Z inclusive. Oregon State College Creed Joseph Brye The A Cappella Choir Robert Walls, Conductor The Oregon State College Creed was written by Dr. Edwin Thomas Reed, emeritus editor of publications. Alma Mater Homer Maris, M .S., '18 Recessional-La Reine de Saba Charles Gounod The College R.O.T.C. -

Daily Bulletin

Friday, December 3, 2010 Volume 83, Number 8 Daily Bulletin 83rd North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Dave Smith Caddies have new job description “Caddy, please!” For years, players’ call for a caddy has been heard at bridge tournaments. These days? Not as much. Caddies used to collect pickup slips with scores written on them and take them to the director. The director Jay Borker and Jan Jansma. would enter them into his computer, and eventually Caddies duties have changed. Working here are Troy Meeker, Corey Kay, Borker, Jansma win determine the winners. Caddy Director Pam Hughes, Mikey Wright, Laura Sterling, Emma Wright With wireless scoring and Diego Blel. Blue Ribbon Pairs devices, caddies aren’t Jay Borker and Jan Jansma, lying second after college students. needed to do that. The devices transfer the result for the first final session, had a solid 60.83% game in “The caddies here are an older group of kids,” each board immediately after it’s played. the last round of the Kaplan Blue Ribbon Pairs to says Hughes. “They are a fantastic group and are “Caddies are still needed,” says Caddy Director win by more than a board. some of the best we’ve had -- very mature and Pam Hughes. “They don’t collect scoring slips, but Second went to Jansma’s countrymen from the focused.” they are still needed to do other things.” Netherlands, Bas Drijver and Sjoert Brink. In third There used to be a group of kids that traveled Hughes says that after the games, caddies clean were Brazilians Miguel Villas-Bois and Joaopaulo to each of the three NABCs.