Welfare Restructuring, Work & Poverty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizenship, Refugees, and the State: Bosnians, Southern Sudanese, and Social Service Organizations in Fargo, North Dakota"

CITIZENSHIP, REFUGEES, AND THE STATE: BOSNIANS, SOUTHERN SUDANESE, AND SOCIAL SERVICE ORGANIZATIONS IN FARGO, NORTH DAKOTA by JENNIFER LYNN ERICKSON A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 11 University of Oregon Graduate School Confirmation of Approval and Acceptance of Dissertation prepared by: Jennifer Erickson Title: "Citizenship, Refugees, and the State: Bosnians, Southern Sudanese, and Social Service Organizations in Fargo, North Dakota" This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Doctor ofPhilosophy degree in the Department ofAnthropology by: Carol Silverman, Chairperson, Anthropology Sandra Morgen, Member, Anthropology Lynn Stephen, Member, Anthropology Susan Hardwick, Outside Member, Geography and Richard Linton, Vice President for Research and Graduate StudieslDean ofthe Graduate School for the University of Oregon. September 4,2010 Original approval signatures are on file with the Graduate School and the University of Oregon Libraries. 111 © 2010 Jennifer Lynn Erickson IV An Abstract ofthe Dissertation of Jennifer Lynn Erickson for the degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy in the Department ofAnthropology to be taken September 2010 Title: CITIZENSHIP, REFUGEES, AND THE STATE: BOSNIANS, SOUTHERN SUDANESE, AND SOCIAL SERVICE ORGAl~IZATIONS IN FARGO, NORTH DAKOTA Approved: _ Dr. Carol Silverman This dissertation is a comparative, ethnographic study ofSouthern Sudanese and Bosnian refugees and social service organizations in Fargo, North Dakota. I examine how refugee resettlement staff, welfare workers, and volunteers attempted to transform refugee clients into "worthy" citizens through neoliberal policies aimed at making them economically self-sufficient and independent from the state. -

CSWS Newsletter Single Pages

2003 FromCenter the SPRING CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN SOCIETY · UNIVERSITY OF OREGON Acting Director Praises Center’s Collaborative Model leave the acting director position at CSWS with much appreciation for the uniqueness and Iimportance of the center, its fine staff, its executive committee, and all the UO and commu- nity affiliates who contribute so much to its work. Why is CSWS so important and unique? There are many reasons, but three stand out for me. One is the collaborative work ethic of the center—CSWS forms partnerships with a range of campus departments and organizations and local, national, and international organizations to get things done. Another is the breadth and interdisciplinary character of the scholarship CSWS produces and facilitates. Thirdly, at a historical moment when much academic research narrows and compartmentalizes our ability to understand the world, CSWS is expanding the horizons of knowledge. An example is the recent trip Reclaiming the Past RIG members Stephanie Wood and Judith Musick took to Mexico with James Fox, head of Special Collec- tions, Knight Library. Their purpose was to establish relationships with archives containing primary sources on gender in early Meso-America and to explore ways these materials, now accessible only locally, could be made available to more people. Another example is the Women, Disability, and International Development event CSWS cosponsored with Mobility International USA and other campus units (including the International Studies Program, Yamada Language Center, Center on Diversity and Community, Disability Services, College of Education, and Division of Student Affairs). CSWS is also special in its commitment to spreading boundary-breaking knowledge beyond the confines of the university. -

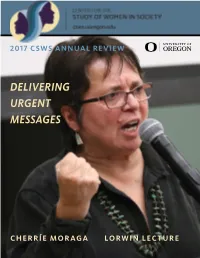

2017 Csws Annual Review

2017 CSWS ANNUAL REVIEW DELIVERING URGENT MESSAGES CHERRÍE MORAGA LORWIN LECTURE COMING UP October 3, 2017 Welcome Reception: New Women Faculty — 4 p.m. Gerlinger. Oct. 12, 2017 “Why Aren’t There CSWS Gets a New Look have been a part of the only feminist research center on a university campus in Oregon. More Black People All of us at CSWS are thrilled to introduce our The curving half of an infinity symbol that in Oregon?: A new wordmark! Designed by Denise Lutz, a local makes up their hair and head scarf is in varying Hidden History,” woman of color and UO alumna, our new word- shades of blue, evoking crescent moons, the pas- Oregon Book Award mark gives a visual representation of who CSWS sage of time, water and its fluidity, and its power winner Walidah is and all that we stand for. We wanted our to harm as well as heal. As CSWS evolves, we will Imarisha—3:30 p.m. new look to express CSWS’s commitment to all Jaqua Center. continue to create change on campus and in our Walidah Imarisha Walidah women and people oppressed by misogyny, from community, not all at once, but over time. We varying walks of life. Feb. 2, 2018 acknowledge the need for strength in the face of Poetry Reading: Joy We see two people—likely women—in sil- adversity, as well as the need to educate those Harjo, American houette, facing away from each other but close who may oppose us, and to never be so rigid that Book Award winner together, joined by hair and head covering. -

Autumn R. Green, Phd [email protected]

Curriculum Vitae Autumn R. Green, PhD [email protected] AREAS OF SOCIOLOGICAL EXPERTISE Poverty, Stratification, Inequality & Mobility Applied & Public Sociology Sociology of Education Evaluation Research Public Policy Arts-Based Research Social Welfare Community-Based/Participatory Action Research Sociology of Families Pedagogical Innovation & 21st Century Learners CURRENT POSITIONS Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts Research Scientist, Wellesley Centers for Women (beginning September) 2018- Visiting Scholar, Wellesley Centers for Women (January-August) 2018 Endicott College, Beverly, Massachusetts Director, National Center for Student Parent Programs 2014-2017 Director, Keys to Degrees National Replication Program 2013-2017 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology 2013-2017 EDUCATION Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts Doctorate of Philosophy in Sociology 2013 Dissertation Title: Babies, Books & Bootstraps: Low-Income Mothers, Material Hardship, Role Strain and the Quest for Higher Education. Committee: Lisa Dodson and C. Shawn McGuffey (co-chairs), Stephen Pfohl, Erika Kates, Sandra Morgen Master of Arts in Sociology 2007 Master’s Thesis: To Strive for More: Women, Welfare, and the Quest for Higher Education Lesley University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2018 Master of Education in Arts, Community & Education – Integrated Arts in Education Concentration Master’s Thesis: In Support of Intergenerational Learning: The Two Generation Classroom as an Innovation in Postsecondary Pedagogy Engaging College Students and -

Joan Acker Has Been on the Faculty at the University of Oregon Since 1966

University of Huddersfield Repository Hearn, Jeff For Joan: Some letters with reverence, an honorary doctorate and a dialogical tribute Original Citation Hearn, Jeff (2017) For Joan: Some letters with reverence, an honorary doctorate and a dialogical tribute. Gender, Work & Organization. ISSN 0968-6673 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34121/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Author’s Copy: This is a so-called personal version (author's manuscript as accepted for publishing after the review process but prior to final layout and copyediting) of the article: [Referens i Harvardformat med länk till originalet]. This version is stored in the Institutional Repository of the Hanken School of Economics, D-HANKEN. Readers are asked to use the official publication in references. -

CSWS Newsletter Winter 05.Indd

2005 FromCenter the WINTER–SPRING CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN SOCIETY · UNIVERSITY OF OREGON Vigilant Attention to Race, Gender, and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A March 1 Panel Discussion Features Three Dynamic Speakers t’s been more than forty years since the will advance ideas and insights about such Mark Your Calendar ICivil Rights and Women’s movements vigilance and compassion. Each has made a demanded equity for all American citizens, significant contribution to the national move- “The Intersection of Race, yet even many of the country’s institutions of ment of gender and race equity. Each is an Gender, and Ethnicity in higher education are still a long way from that outstanding scholar who’s put her vision into Higher Education,” goal. That includes the University of Oregon. practice in diverse institutional contexts. Tuesday, March 1; 3:30 According to the UO Office of Affirmative Ac- p.m.; 175 Knight Law Gertrude Fraser tion, women continue to be underrepresented Center, 1515 Agate St. is currently vice in eleven of the university’s forty-seven job Followed by a reception provost for fac- groups, and people of color are underrepre- in the commons area. ulty advancement sented in fourteen of those forty-seven job at the University of groups. Virginia, and was On Tuesday, March 1, 2005, three scholars formerly a program providing leadership in the arena of racial director special- and gender equity in higher education will izing in education visit the UO to speak about ways to move and scholarship forward in that pursuit. The panel, entitled with the Ford Foundation in New York. -

CSWS Newsletter Fall 03

2003 FromCenter the FALL–WINTER CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN SOCIETY · UNIVERSITY OF OREGON Interrogating Security: Campus Collaborations Promote Critical Inquiry t has been two years since the events of September 11 unleashed a new era in U.S. domes- tic and foreign policy. In the name of national security U.S. political leaders have enacted Iand proposed further curtailments of civil liberties, practiced pre-emptive military action and “regime change,” and diverted billions of dollars from national and international programs to promote health, education, and human services to sustain a costly (in terms of human life and money) military presence in Iraq. Clearly this is a moment to interrogate the meaning of security and to carefully consider how different domestic and foreign policies foster security and for whom. CSWS is pleased to announce two campus collaborations that promise to create opportunities for faculty, students, and the larger community to critically examine the meanings and various paradigms of security as well as the foreign and domestic policies that promise to enhance or undermine real security for the world’s peoples, including our own national security. Over the next three years CSWS will collaborate with the Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics, Women's and Gender Studies, and the Carlton Raymond and Wilberta Ripley Savage Professorship in International Relations and Peace in organizing a series of events—a conference, speakers, seminars, courses, and films—to generate critical inquiry about gender, race, class, security, globalization, and militarization. This year’s activities involve collabora- tion between the Women in the Northwest Initiative (CSWS) and the Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics. -

CSWS Newsletter Single Pages

2002 FromCenter the AUTUMN CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN SOCIETY · UNIVERSITY OF OREGON Creativity, Collaboration, Communities— Celebrating the Past, Looking to the Future n this issue of the newsletter, we announce our new annual membership campaign and new Icommunity programs. As we look toward the future, we also look back on three decades of energy, enthusiasm, and innovative scholarship that have built a research center with an international reputation for excellence. Generating, supporting, and disseminating research on women—many readers of this newsletter will recognize these now familiar goals of CSWS. But what does it mean to gener- ate, support, and disseminate research on women? It means forming initiatives to increase knowledge about how gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexual identity, and culture shape women’s lives and affect their social well being. It means publishing groundbreaking studies on welfare reform and poverty that are enabling activists and legislators to make informed decisions. It means developing a virtual library of resources on women and history for teachers, students, and researchers, enabling scholarly collabora- tions and classroom access to reproductions of rare manuscripts that were unthinkable before. It means receiving $4 million in government grants to conduct research on women’s reproduc- tive health and to sponsor educational trials for young minorities at risk. It means awarding more than one and one-half million dollars in grants to UO faculty members and graduate students, resulting in completed Ph.D. dissertations, books, and articles. It means more Ph.D. degrees and more tenured and promoted women faculty mem- bers. It means making possible more equitable gender content across the curriculum. -

CSWS Newsletter

2004 FromCenter the SPRING CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN SOCIETY · UNIVERSITY OF OREGON The Borders of Human Security: Bringing Geopolitics Home ow are economic security, hu- the international policy community. Heyzer, man and civil rights, and national who received her education at the Univer- Hsecurity related in our lives? In what sity of Singapore and Cambridge University, ways are globalization and militarization has been at the helm of UNIFEM since 1994 racialized and gendered processes producing advocating models of development that pro- security for some and vulnerabilities for oth- mote economic security and the empower- ers? How might international, national, and ment of women and their families. In addi- local security policies be different if their tion to work with women migrant workers at core goals included the community level, reducing poverty, workers in the informal violence, and racial, sector and free trade ethnic, and gender zones, and women inequalities? These are who have experienced some of the questions domestic and other to be addressed by an forms of violence, eminent group of social Heyzer has also been a scientists, lawyers, policy adviser to Asian labor leaders, and com- governments and a munity advocates at a founding member of conference sponsored such groups as Devel- by CSWS May 20–21, opment Alternatives 2004. with Women for a New INSIDE The borders we will Era (DAWN). examine are both material and metaphorical. A series of panels on Friday features centerview .............. 2 They are policed national and community distinguished scholars and advocates who borders. They are limits and restrictions that will discuss the effects of violence that upcoming...............