CORRECTED TRANSCRIPT of ORAL EVIDENCE to Be Published As HC 371-Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summing up in the Senedd (Assembly) 3) News from the European Parliament If You Have Any Feedback Let Us Know by Emailing [email protected]

This is the fourth edition of the Brexit Briefing, we hope you enjoy. Much more information about all of these issues can be found on the Brexit Section of our website. There are three parts to the Briefing: 1) News from the Imperial Capital (Westminster) 2) Summing up in the Senedd (Assembly) 3) News from the European Parliament If you have any feedback let us know by emailing [email protected]. Summing up in the Senedd By our Assembly Brexit Spokesman Steffan Lewis AM and the Assembly Team Last weekend, Andrew RT Davies, the leader of the Conservatives in Wales, claimed that powers over agriculture should be returned to Westminster when the UK leaves the EU because farmers ‘do not trust’ the Welsh Government. Agricultural policy is currently devolved and the Welsh Government will gain the power to review and amend over 200 pieces of EU regulation that underpin Welsh environmental law after Brexit. Simon Thomas AM, Plaid Cymru rural affairs spokesperson, slammed Andrew RT Davies’s comments, saying in fact that ‘the Tories simply cannot be trusted to defend rural Wales’. He said, “the UK Government has completely failed to offer any security to farmers whose livelihoods are on the line. With this attitude being adopted by the Westminster government, it is absurd and irresponsible for the Leader of the Conservatives in Wales to claim that farming subsidies would be better administered from London.” Steffan Lewis has argued that greater cooperation between Ireland and Wales will be necessary to help us deal with the post-Brexit context. A ‘Celtic Sea Alliance’ should be established between the two nations, and especially between the western regions of Wales and the eastern regions of Ireland. -

Europe Matters

National Assembly for Wales EU Office Europe Matters Issue 30 – Summer/Autumn 2014 The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales and holds the Welsh Government to account. © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2014 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. Introduction Dame Rosemary Butler AM Presiding Officer I am delighted to introduce the 30th issue of Europe Matters, our update on the work of the National Assembly for Wales on European issues. It was a privilege and an honour to participate on 16 August at the inauguration of the Welsh Memorial in Langemark, Flanders, to the Welsh soldiers who lost their lives in Flanders Fields during the First World War. Over 1,000 people from Wales and Flanders attended the ceremony, including the three leaders of the opposition parties in the Assembly, Andrew RT Davies AM, Leanne Wood AM and Kirsty Williams AM, and of course the First Minister Carwyn Jones AM. I and my fellow Commissioners, Sandy Mewies AM and Rhodri Glyn Thomas AM, will attend a special commemoration in Flanders next month, at the invite of the President of the Flemish Parliament Jan Peumans. This is another example of the strong co-operation and warmth between our two nations. -

Environmental Principles and Governance Post-Brexit

Environmental principles and governance post-Brexit October 2019 www.assembly.wales The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the National Assembly website: www.assembly.wales/SeneddCCERA Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddCCERA © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2019 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. Environmental principles and governance post-Brexit October 2019 www.assembly.wales About the Committee The Committee was established on 28 June 2016. Its remit can be found at: www.assembly.wales/SeneddCCERA Committee Chair: Mike Hedges AM Welsh Labour Current Committee membership: Andrew RT Davies AM Llyr Gruffydd AM Welsh Conservatives Plaid Cymru Neil Hamilton AM Jenny Rathbone AM UKIP Wales Welsh Labour Joyce Watson AM Welsh Labour The following Members were also members of the Committee during this inquiry John Griffiths AM Dai Lloyd AM Welsh Labour Plaid Cymru Environmental principles and governance post-Brexit Contents Overview ................................................................................................................... -

SW1A 0AA 11 March 2021 Rt Hon Mark

HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON SW1A 0AA 11 March 2021 Rt Hon Mark Drakeford MS First Minister Welsh Government 5th Floor Tŷ Hywel Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Sent by email to [email protected] Dear First Minister We are writing to you on behalf of the Welsh farming community to voice our serious concerns at the outcome of the recent Senedd vote on annulling The Water Resources (Control of Agricultural Pollution) (Wales) Regulations 2021. You and 29 other Members voted against annulment. Members of both the FUW and NFU Cymru have written to us to say that, in classifying the whole of Wales as a Nitrate Vulnerable Zone, the Welsh Government has put their livelihoods at risk. The huge upfront investment required to comply with the regulations will make their businesses unviable and uncompetitive, causing massive damage to the sector. In fact, we are aware that the Regulations are already having a detrimental impact on the mental health of many in agriculture. Undoubtedly, this should come as no surprise to you when considering the warning that this might happen in your own Explanatory Memorandum. However, what is alarming is that your Welsh Government have pursued the NVZ regardless of the concerns raised about farmers’ health and wellbeing. Alongside agriculture, there could also be a potentially negative impact on the environment. Suckler cow herds have been declining in Wales. These herds provide a very important contribution to biodiversity, managing some of our most important habitats. Some farmers are already warning us that they are now looking to give up keeping cattle. -

The Impact of Brexit on Fisheries in Wales

National Assembly for Wales Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee The impact of Brexit on fisheries in Wales October 2018 www.assembly.wales The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the National Assembly website: www.assembly.wales/SeneddCCERA Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddCCERA © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2018 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. National Assembly for Wales Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee The impact of Brexit on fisheries in Wales October 2018 www.assembly.wales About the Committee The Committee was established on 28 June 2016. Its remit can be found at: www.assembly.wales/SeneddCCERA Committee Chair: Mike Hedges AM Welsh Labour Swansea East Current Committee membership: Gareth Bennett AM Jayne Bryant AM UKIP Wales Welsh Labour South Wales Central Newport West Andrew RT Davies AM John Griffiths AM Welsh Conservatives Welsh Labour South Wales Central Newport East Dai Lloyd AM Joyce Watson AM Plaid Cymru Welsh Labour South Wales West Mid and West Wales The following Members were also members of the committee during this inquiry. -

Oral Assembly Questions Tabled on 25/09/2019 for Answer on 02/10/2019

Oral Assembly Questions tabled on 25/09/2019 for answer on 02/10/2019 The Presiding Officer will call party spokespeople to ask questions without notice after Question 2. Minister for Economy and Transport Neil McEvoy South Wales Central 1 OAQ54424 (e) Will the Minister make a statement on public transport provision in Cardiff? Angela Burns Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire 2 OAQ54430 (e) What plans does the Welsh Government have to assist small business growth in Wales? Leanne Wood Rhondda 3 OAQ54419 (e) Will the Minister provide an update on the roll-out of new trains for the Rhondda as part of the new rail franchise? Llyr Gruffydd North Wales 4 OAQ54423 (w) Will the Minister make a statement on how the Welsh Government will improve disabled access to railways in Wales? Vikki Howells Cynon Valley 5 OAQ54410 (e) What discussions has the Minister had about maximising the benefits of the construction of sections 5 and 6 of the A465 Heads of the Valleys road? Paul Davies Preseli Pembrokeshire 6 OAQ54404 (e) Will the Minister make a statement on support for small businesses in Pembrokeshire? Huw Irranca-Davies Ogmore 7 OAQ54441 (e) Will the Minister provide an update on the work being carried out to extend the frequency of rail services on the Maesteg line? Russell George Montgomeryshire 8 OAQ54414 (e) Will the Minister make a statement on the planned improvements to transport infrastructure in mid-Wales? Lynne Neagle Torfaen 9 OAQ54412 (e) What steps is the Welsh Government taking to improve bus services in the south Wales valleys? -

VALE of GLAMORGAN AGRICULTURAL SHOW Wednesday, 10Th August, 2016 Fonmon Castle Grounds Vale of Glamorgan SCHEDULE

VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGRICULTURAL SHOW Wednesday, 10th August, 2016 Fonmon Castle Grounds Vale of Glamorgan SCHEDULE www.valeofglamorganshow.co.uk Entries close on Saturday 16th July Late entries will not be accepted Registered Charity No. 1108960 supported by nathanielmitsubishi.co.uk AT NFU MUTUAL OUR EXPERTS CAN POINT YOU IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION Need advice about securing your financial future? Pop in for a chat at the Bridgend and The Vale branch, contact us at [email protected] or telephone 01656 349556 . NFU Mutual Financial Advisers advise on NFU Mutual products and selected products from specialist providers. When you get in touch we’ll explain the advice services we offer and our charges. www.nfumutual.co.uk/bridgend Our agents are appointed representatives for general insurance products and introducer appointed representatives for life, pensions and investments of NFU Mutual. Our staff introduce to NFU Mutual for life, pensions and investments. NFU Mutual is The National Farmers Union Mutual Insurance Society Limited (No. 111982). Registered in England. Registered Office: Tiddington Road, Stratford upon Avon, Warwickshire CV37 7BJ. Authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and by the Prudential Regulation Authority. A member of the Association of British Insurers. 1 For security and training purposes, telephone calls may be recorded and monitored. The Vale of Glamorgan Agricultural Society President: Mr. Andrew RT Davies, AM Vice-Presidents: Mayor of The Vale of Glamorgan Council The Mayor of Cowbridge with Llanblethian Town Council Mr. David James Show Chairman: Mrs. Elizabeth Synan Show Vice-Chairman: Mr. Lynn Price Show Director: Mr. -

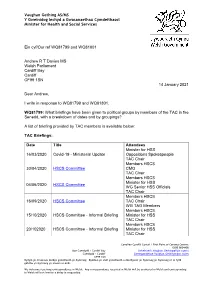

Information Further to Written Question 81799 81801

Vaughan Gething AS/MS Y Gweinidog Iechyd a Gwasanaethau Cymdeithasol Minister for Health and Social Services Ein cyf/Our ref WQ81799 and WQ81801 Andrew R T Davies MS Welsh Parliament Cardiff Bay Cardiff CF99 1SN 14 January 2021 Dear Andrew, I write in response to WQ81799 and WQ81801: WQ81799: What briefings have been given to political groups by members of the TAC in the Senedd, with a breakdown of dates and by groupings? A list of briefing provided by TAC members is available below: TAC Briefings: Date Title Attendees Minister for HSS 16/03/2020 Covid-19 - Ministerial Update Oppositions Spokespeople TAC Chair Members HSCS 30/04/2020 HSCS Committee CMO TAC Chair Members HSCS Minister for HSS 04/06/2020 HSCS Committee WG Senior HSS Officials TAC Chair Members HSCS 16/09/2020 HSCS Committee TAC Chair WG TAG Members Members HSCS 15/10/2020 HSCS Committee - Informal Briefing Minister for HSS TAC Chair Members HSCS 20/102020 HSCS Committee - Informal Briefing Minister for HSS TAC Chair Canolfan Cyswllt Cyntaf / First Point of Contact Centre: 0300 0604400 Bae Caerdydd • Cardiff Bay [email protected] Caerdydd • Cardiff [email protected] CF99 1SN Rydym yn croesawu derbyn gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg. Byddwn yn ateb gohebiaeth a dderbynnir yn Gymraeg yn Gymraeg ac ni fydd gohebu yn Gymraeg yn arwain at oedi. We welcome receiving correspondence in Welsh. Any correspondence received in Welsh will be answered in Welsh and corresponding in Welsh will not lead to a delay in responding. Adam Price MS Rhun ap Iorwerth -

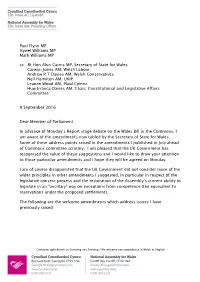

Letter from Llywydd to Welsh Mps: Amendments

Paul Flynn MP Hywel Williams MP Mark Williams MP cc Rt Hon Alun Cairns MP, Secretary of State for Wales Carwyn Jones AM, Welsh Labour Andrew R T Davies AM, Welsh Conservatives Neil Hamilton AM, UKIP Leanne Wood AM, Plaid Cymru Huw Irranca-Davies AM, Chair, Constitutional and Legislative Affairs Committee 9 September 2016 Dear Member of Parliament In advance of Monday’s Report stage debate on the Wales Bill in the Commons, I am aware of the amendments now tabled by the Secretary of State for Wales. Some of these address points raised in the amendments I published in July ahead of Commons committee scrutiny. I am pleased that the UK Government has recognised the value of these suggestions and I would like to draw your attention to those particular amendments and I hope they will be agreed on Monday. I am of course disappointed that the UK Government did not consider more of the wider principles in other amendments I suggested, in particular in respect of the legislative consent process and the restoration of the Assembly’s current ability to legislate in an “ancillary” way on exceptions from competence (the equivalent to reservations under the proposed settlement). The following are the welcome amendments which address issues I have previously raised: Croesewir gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg neu Saesneg / We welcome correspondence in Welsh or English Clause Purpose Tabled Amendment Number Clause 1: These amendments move the section on SoSW 3,4,5,6,7 Permanence permanence of NAW and Welsh Government and 8 of NAW/WG to the beginning of GOWA 2006. -

Gareth Bennett AM * Andrew RT Davies AM UKIP Wales Welsh Conservatives South Wales Central South Wales Central

National Assembly for Wales Standards of Conduct Committee Report 03-18 to the Assembly under Standing Order 22.9 November 2018 www.assembly.wales The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the National Assembly website: www.assembly.wales/SeneddStandards Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Standards of Conduct Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2018 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. National Assembly for Wales Standards of Conduct Committee Report 03-18 to the Assembly under Standing Order 22.9 November 2018 www.assembly.wales About the Committee The Committee was established on 28 June 2016 to carry out the functions of the responsible committee set out in Standing Order 22. These include: the investigation of complaints referred to it by the Standards Commissioner; consideration of any matters of principle relating to the conduct of Members; establishing procedures for the investigation of complaints; and arrangements for the Register of Members’ interests and other relevant public records determined by Standing Orders. -

The Government and Politics of Wales Questions for Discussion and Case Studies Chapter 2

Government and Politics of Wales – Teaching Support Material Chapter 2 1 The Government and Politics of Wales Questions for discussion and case studies Chapter 2 – Welsh Politics, Ideology and Political Parties Pages 22–44, Authors Alison Denton and Russell Deacon Teacher’s guide – in conjunction with the text book Timing: Students should read the relevant chapter before undertaking the exercise questions and case studies, and discuss their answers. There are answer note suggestions behind all questions. The questions can be undertaken in class or at home with questions/answers and activities being undertaken in the classroom. The material is teaching material and NOT specifically material for answering examination questions. Tutor guide: Tutors should familiarise themselves with the text, questions and answers before undertaking the activities in the classroom. For any unfamiliar terms an extensive glossary of key terms is provided on pages 206–22 of the book. The questions and case studies do not cover all of the material in the chapters. If tutors wish to cover this, they will need to set additional stimulus questions. Tutors and students may also wish to add material not provided in either the suggested answers or the text to the answers. Welsh politics is constantly changing, so answers provided now may well alter as these changes take place. The questions for discussion and the case studies are found at the end of each chapter. The suggested answers and some ideas for teaching these are provided on the following pages. Tutors should seek to draw these answers from the students and also discuss their merits. -

BREXIT at a GLANCE... What Happened This Week

BREXIT AT A GLANCE... Weekly news, views and insights from the Welsh NHS Confederation Friday, 20 September Please cascade information where appropriate to your workforce and care providers What Happened This Week... With less than 6 weeks to go until Brexit, UK Parliament remains prorogued, with little progress being shown. The Supreme Court case determining whether prorogation is lawful concluded, with the ruling due early next week. EU officials publicly rejected Boris Johnson’s claim that “a huge amount of progress” was being made in Brexit talks, as the President of the European Commission warned that time is running out, if a deal was to be made. However, in Wales there have been some subtle but significant shifts. Welsh Government published their no-deal action plan, in response to the UK Government’s Yellowhammer documents. One of the key actions included, investing in a new NHS warehouse to provide additional storage capacity for medical devices. The plan sets out the potential consequences of a no deal Brexit on all aspects of Welsh life. The plan summarises the measures being taken to help to limit some of the worst effects of leaving without a deal. We attended the EU Transition Health and Social Services Leadership and SRO Group meetings at Welsh Government. The Welsh NHS Confederation are committed to working with our members and the Welsh Government to ensure the health and care sector are fully prepared in the possibility of a no- deal Brexit. EU citizen living in Wales and who are concerned about applying for EU settled-status should look at the new Immigration Advice Service launched by Welsh Government and immigration specialists Newfields Law.