Operational Assessment and Identified Efficiency Opportunities Indianapolis Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Justice for All: Indiana’S Federal Courts

And Justice for All: Indiana’s Federal Courts Teacher’s Guide Made possible with the support of The Historical Society of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Inc. Indiana Historical Society Heritage Support Grants are provided by the Indiana Historical Society and made possible by Lilly Endowment, Inc. The R. B. Annis Educational Foundation Indiana Bar Association This is a publication of Gudaitis Production 2707 S. Melissa Court 812-360-9011 Bloomington, IN 47401 Copyright 2017 The Historical Society of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Inc. All rights reserved The text of this publication may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the written permission of the copyright owner. All inquiries should be addressed to Gudaitis Production. Printed in the United States of America Contents Credits ............................................................................................................................iv Introduction .....................................................................................................................1 Curriculum Connection ..................................................................................................1 Objectives ........................................................................................................................3 Video Program Summary ...............................................................................................3 -

Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 265 562 CS 209 541 AUTHOR Gibbs, Sandra E., Comp. TITLE Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE Mar 86 NOTE 88p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Awards; Creative Writing; Evaluation Criteria; Layout (Publications); Periodicals; Secondary Education; *Student Publications; Writing Evaluation IDENTIFIERS Contests; Excellence in Education; *Literary Magazines; National Council of Teachers of English ABSTRACT In keeping with efforts of the National Council of Teachers of English to promote and recognize excellence in writing in the schools, this booklet presents the rankings of winning entries in the second year of NCTE's Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines in American and Canadian schools, and American schools abroad. Following an introduction detailing the evaluation process and criteria, the magazines are listed by state or country, and subdivided by superior, excellent, or aboveaverage rankings. Those superior magazines which received the program's highest award in a second evaluation are also listed. Each entry includes the school address, student editor(s), faculty advisor, and cost of the magazine. (HTH) ***********************************************w*********************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** National Council of Teachers of English 1111 Kenyon Road. Urbana. Illinois 61801 Programto Recognize Excellence " in Student LiteraryMagazines UJ 1985 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Vitusdocument has been reproduced as roomed from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction Quality. -

Shortridge High School

REINVENTING IPS HIGH SCHOOLS Facility Recommendations to Strengthen Student Success in Indianapolis Public Schools June 28, 2017 1 Table of Contents i. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 ii. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 iii. School Profiles ............................................................................................................................................................ 10 a. Arlington High School ............................................................................................................................................................... 10 b. Arsenal Technical High School ............................................................................................................................................... 11 c. Broad Ripple High School ......................................................................................................................................................... 12 d. Crispus Attucks High School ................................................................................................................................................... 13 e. George Washington High School ......................................................................................................................................... -

Other Basketball Leagues

OTHER BASKETBALL LEAGUES {Appendix 2.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 14} Research completed as of July 10, 2013 AMERICAN BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION (ABA) Team: Arizona Scorpions Principal Owner: Ron Tilley Team Website Arena: Phoenix College Team: Atlanta Aliens Principal Owner: Adrian Provost Team Website Arena: Ben Hill Arena Team: Atlanta Wildcats Principal Owner: William D. Payton IV Team Website Arena: Lynnwood Recreation Center © Copyright 2013, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Bahama All-Pro Show Principal Owner: Ricardo Smith Team Website: N/A Arena: Loyola Hall UPDATE: The Bahama All-Pro Show is a team of all Bahamian players who play sporadically in the ABA. In 2012 they were placed on the schedule but never played a game. Team: Bay Area Matrix Principal Owner: Jim Beresford Team Website Arena: Diablo Valley College Team: Birmingham Blitz Principal Owner: Ron Steele, Jr. Team Website Arena: Bill Harris Arena Team: Brooklyn Blackout Principal Owner: Onez Onassis and Neal Booker Team Website: N/A Arena: Aviator Sports Center Update: On May 8, 2013, it was announced that Brooklyn would be an ABA expansion team. © Copyright 2013, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 2 Team: Calgary Crush Principal Owner: Salman Rashidian Team Website Arena: SAIT Polytechnic Team: Central Valley Titans Principal Owner: Josh England Team Website Arena: Exeter Union High School Team: Chicago Court Kingz Principal Owner: Unique Starz Sports & Entertainment Team Website: N/A Arena: N/A UPDATE: The ABA announced on May 18, 2013 that the Chicago Court Kingz would begin play during the 2013–14 season. -

One Hundred Fifty Years in Broad Ripple

ONE HUNDRED FIFTY YEARS IN BROAD RIPPLE CELEBRATING METHODISM’S OUTPOST FOR PREACHING THE GOSPEL IN BROAD RIPPLE 1852-2002 Compiled, written, and edited by Donald E. Mattson, 150th Anniversary Celebration Committee Broad Ripple United Methodist Church PREFACE Our introduction to Broad Ripple remains etched in my memories. A serendipitous event brought us into this fellowship. Thirty-three years ago on the Sunday following Labor Day, Carol and I went “church shopping.” We had just moved to a home in Butler-Tarkington that week. While shopping at Kroger’s, Carol saw a Methodist church and suggested we visit it. I recall sitting near the front on the right side. After the organist finished playing the prelude, there was silence. Then, Jim Rodeheffer stood in a row behind us and began singing, Come Christians, Join to Sing! Other choir members joined with him and moved to the choir loft. Dr. Floyd Cook, the minister, sat at the other end of our pew and took his place. We both enjoyed our experience that morning and never visited another church. Carol joined the choir and we found in the choir an extended family embracing first us and then Erick and Erin. In December 2001, Laura Eller, the Celebration Committee Chair, asked me to compile the congregation’s history. I knew I faced challenges. Previous histories revealed substantial gaps. I began my research with a dusty box of records in the stage storeroom plus others I found in the attic. Further research required visits to the library at Christian Theological Seminary, the microfilm room at the Central Library, the Indiana Historical Society, the Indiana State Library, and the Methodist Archives at DePauw University. -

2016 Football Media Guide-Color.Indd

Washington State | #GoCougs QUICK FACTS WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY QUICK FACTS COACHING STAFF FOUNDED: 1890 HEAD COACH: Mike Leach (BYU ‘83) NICKNAME: Cougars CAREER RECORD (Years): 105-76 (14) WSU RECORD (Years): 21-29 (4) COLORS: Crimson and Gray STAFF: CONFERENCE: Pac-12 Dave Emerick, Senior Associate A.D./Chief of Staff, 5th Year ENROLLMENT: 19,556 Alex Grinch, Defensive Coordinator, 2nd Year LOCATION: Antonio Huffman, Director of Football Operations, 5th Year P. O. Box 641602 Jason Loscalzo, Head Football Strength and Conditioning Coach, 5th Year Pullman, WA 99164-1602 Roy Manning, Outside Linebackers, 2nd Year STADIUM: Martin Stadium (32,952 - Field Turf) Jim Mastro, Running Backs, 5th Year PRESIDENT: Kirk H. Schulz Clay McGuire, Offensive Line, 5th Year ATHLETIC DIRECTOR: Bill Moos Eric Mele, Special Teams, 2nd Year FACULTY ATHLETIC REP: Ken Casavant Dave Nichol, Outside Receivers, 1st Year Joe Salave’a, Assistant Head Coach/Defensive Line, 5th Year TICKET OFFICE: 509-335-9626, 800-GO-COUGS JaMarcus Shephard, Inside Receivers, 1st Year GENERAL DEPARTMENT: 509-335-0311 Ken Wilson, Linebackers, 4th Year WSU ATHLETICS FAX: 509-335-5197 Gordy Anderson, Manager of Player Personnel, 2nd Year WSU FOOTBALL OFFICE: 509-335-0250 David Lose, Defensive Assistant, 6th Year WSU ATHLETICS WEBSITE: www.wsucougars.com Brian Odom, Defensive Quality Control, 2nd Year Price Ferguson, Offensive Quality Control, 1st Year WSU ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS Chase Holbrook, Offensive Quality Control, 1st Year OFFICE ADDRESS: Drew Hollingshead, -

2016 Football Spring Guide.Indd

WASHINGTON STATE COUGARS 2016 SPRING FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE # GoCougs | WSUCougars.com QUICK FACTS WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY QUICK FACTS COACHING STAFF FOUNDED: 1890 HEAD COACH: Mike Leach (BYU ‘83) NICKNAME: Cougars CAREER RECORD (Years): 105-76 (14) COLORS: Crimson and Gray WSU RECORD (Years): 21-29 (4) CONFERENCE: Pac-12 STAFF: Dave Emerick, Senior Associate A.D./Chief of Staff, 5th Year ENROLLMENT: 19,756 Alex Grinch, Defensive Coordinator, 2nd Year LOCATION: Antonio Huffman, Director of Football Operations, 5th Year P. O. Box 641602 Jason Loscalzo, Head Football Strength and Conditioning Coach, 5th Year Pullman, WA 99164-1602 Roy Manning, Outside Linebackers, 2nd Year STADIUM: Martin Stadium (32,952 - Field Turf) Jim Mastro, Running Backs, 5th Year INTERIM PRESIDENT: Dr. Daniel J. Bernardo Clay McGuire, Offensive Line, 5th Year ATHLETIC DIRECTOR: Bill Moos Eric Mele, Special Teams, 2nd Year FACULTY ATHLETIC REP: Ken Casavant Dave Nichol, Outside Receivers, 1st Year TICKET OFFICE: 509-335-9626, 800-GO-COUGS Joe Salave’a, Assistant Head Coach/Defensive Line, 5th Year GENERAL DEPARTMENT: 509-335-0311 JaMarcus Shephard, Inside Receivers, 1st Year Ken Wilson, Linebackers, 4th Year WSU ATHLETICS FAX: 509-335-5197 Gordy Anderson, Manager of Player Personnel, 2nd Year WSU FOOTBALL OFFICE: 509-335-0250 David Lose, Defensive Assistant, 6th Year WSU ATHLETICS WEBSITE: www.wsucougars.com Brian Odom, Defensive Quality Control, 2nd Year Price Ferguson, Offensive Quality Control, 1st Year WSU ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS Chase -

Accredited Secondary Schools in the United States. Bulletin 1916, No. 20

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1916, No. 20 ACCREDITED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES SAMUEL PAUL CAPEN SPECIALIST IN HIGHER EDUCATION BUREAU OF EDUCATION WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 *"■*■ - . ■-■■^■■- ' ' - - - ' _ >ia •;• ••••*•--•. ,-. :~= - c.v - - : , • . v ••. • ‘ ' - . ' ' • - -:;...*- ■ - -v v H m - ;. -- . .' ' " --4' rV'wV'* -w'' A/-O -V ' ^ -v-a 'Ufti _' f - ^3^ ^ DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1916, No. 20 ACCREDITED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES BY SAMUEL PAUL CAPEN SPECIALIST IN HIGHER EDUCATION BUREAU OF EDUCATION WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education, Washington. Sir: Many students apply for admission to higher institutions in other States and sections than those in which they have received their high-school preparation. Many also seek certificates from ex¬ amining and licensing boards, which have no direct means of know¬ ing the standards of the schools from which the applicants come. The demand for this information led the Bureau of Education, first in the spring of 1913 and again in the autumn of 1914, to undertake the collection and preparation of lists of high schools and academies accredited by State universities, approved by State departments of education, or recognized by examining and certifying boards and by certain other agencies. The demand proved to be even greater than had been anticipated. The first edition of the bulletin was soon exhausted. There have be^n many requests from college and uni¬ versity officers for copies of the second edition. Moreover, changes are made in these lists of accredited schools from year to year. -

2012 Mcdonald's All American Games Nominees BOYS

2012 McDonald's All American Games Nominees BOYS NOMINEES ALABAMA First Last School Name City State Daniel Beauchamp Northside Methodist Academy Dothan AL Kendall Moore Cornerstone Christian School Columbiana AL Jordan Randolph Patrician Academy Bulter AL Craig Sword Carver High School Montgomery AL ARIZONA First Last School Name City State Kareem Canty Westwind Preparatory Academy Phoenix AZ Archie Goodwin Sylvan Hills High School Sherwood AZ Demarquise Johnson Westwind Academy Phoenix AZ Kenny Martin Raymond S. Kellis High School Glendale AZ Je Zhe Newton Chandler High School Chandler AZ Richard Peters Phoenix Westwind Prep Phoenix AZ Calaen Robinson Corona del Sol High School Tempe AZ CALIFORNIA First Last School Name City State Zena Edosomwan Harvard-Westlake High School Studio City CA Grant Jerrett La Verne Lutheran High School La Verne CA Xavier Johnson Mater Dei School Santa Ana CA Katin Reinhardt Mater Dei High School Santa Ana CA Robert Upshaw San Joaquin Memorial Fresno CA Grant Verhoeven Central Valley Christian Visalia CA Tyrone Wallace Bakersfield High School Bakersfield CA Gabe York Orange Lutheran High School Orange CA COLORADO First Last School Name City State Wesley Gordon Sierra High School Colorado Springs CO Josh Scott Lewis-Palmer High School Monument CO CONNECTICUT First Last School Name City State Kris Dunn New London High School New London CT Ben Freeland Suffield Academy Suffield CT Ricardo Ledo South Kent School South Kent CT Timajh Parker St. Joseph High School Trumbull CT Erik Sanders Suffield Academy Suffield CT FLORIDA First Last School Name City State Ian Baker Arlington Country Day School Jacksonville FL Ismail Douda Grandview Prep Boca Raton FL Michael Frazier Montverd High School Montverd FL Jordon Goodman Arlington Country Day School Jacksonville FL Torian Graham Arlington Country Day School Jacksonville FL Demetrius Henry North East High School St. -

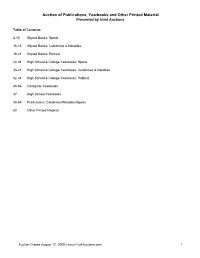

Augustfinalip Sorted

Auction of Publications, Yearbooks and Other Printed Material Presented by Hunt Auctions Table of Contents 2-15 Signed Books: Sports 16-18 Signed Books: Celebrities & Notables 19-21 Signed Books: Political 22-34 High School & College Yearbooks: Sports 35-41 High School & College Yearbooks: Celebrities & Notables 42-44 High School & College Yearbooks: Political 45-56 Collegiate Yearbooks 57 High School Yearbooks 58-59 Publications: Celebrities/Notables/Sports 60 Other Printed Material Auction Closes August 12, 2009 | www.HuntAuctions.com 1 Auction of Publications, Yearbooks and Other Printed Material Presented by Hunt Auctions Signed Books: Sports 195 Hank Aaron signed "Aaron" hardcover book. (EX/MT) 306 Hank Aaron and Lonnie Wheeler signed "I Had A Hammer" hardcover book. (EX-EX/MT) 100 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar signed "Rookie the World of the NBA" hardcover book by David Klein. (EX) 106 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar signed "Stand Tall" hardcover book by Phil Pepe. (EX) 131 Tommie Agee, Cleon Jones, and Ron Swoboda multi-signed "A Magic Summer" hardcover book. (EX-EX/MT) 83 Muhammad Ali signed book His Life and Times (EX/MT) 90 Muhammad Ali signed Neil Leifer book Memories (EX/MT) 91 Muhammad Ali signed Neil Leifer book Memories (EX/MT) 94 Muhammad Ali twice signed book The Greatest (EX-EX/MT) 1443 Muhammad Ali signed book My Own Story (EX-EX/MT) 1444 Muhammad Ali signed book A View from the Corner (EX-EX/MT) 1445 Muhammad Ali signed book In This Corner (EX-EX/MT) 1446 Muhammad Ali signed book The Fighting Prophet (EX-EX/MT) 299 Mel Allen (d.1996) signed "The Men Of Autumn" hardcover book. -

Morse Reservoir Charity Event Hitting the Water Next Month

TODAy’s WeaTHER SATURDAY, JULY 7, 2018 Today: Sunny. Tonight: Clear. SHERIDAN | NOBLESVILLE | CICERO | ARCADIA IKE TLANTA ESTFIELD ARMEL ISHERS NEWS GATHERING L & A | W | C | F PARTNER FOLLOW US! HIGH: 80 LOW: 59 Noblesville mourns loss of hero of 1983 fire The REPORTER Retired Noblesville Firefighter Harold “Sandy” Lykes recently passed away at the age of 64. Lykes was hired as a fireman by the Noblesville Fire Department on Nov. 1, 1977. He was severely injured during the Noblesville Rup- pert Furniture Store fire on Jan. 21, 1983. Lykes suf- fered a skull frac- Photo provided ture and the loss Just like last year, Morse Reservoir will be filled with people racing for Guardian Angels Medical Service Dogs next month. of an arm while Lykes fighting the fire. Despite several months of rehabilitation, Lykes was not able to return to work. He Morse Reservoir charity event continued to serve the Noblesville com- munity as a parking meter attendant from November 1983 to May 1988. “I offer my condolences and heartfelt hitting the water next month sympathy to the Lykes family,” said May- or John Ditslear. “As an NFD firefighter, The REPORTER Sandy was dedicated to the community in Shaka SUP Racing is once again bring- which he served. Sandy was tragically in- ing paddle racing fun and competition to jured in the Noblesville Ruppert Furniture Morse Reservoir. Whether you are a stand Store fire and it serves as a reminder of how up paddle boarder or kayaker, they have a dangerous the profession is for our public course for you: Short course for the youth safety and first responder employees.” and beginners and distance course for expe- rienced paddlers. -

All Is Quiet— for the Moment Uindy Is Embarking on an Ambitious Five-Year Plan to Transform the Campus and the Community

The Magazine of the University of Indianapolis Spring 2014 All is quiet— for the moment UIndy is embarking on an ambitious five-year plan to transform the campus and the community. Krannert Memorial Library will be reinvented. Plus, a new health sciences center is coming— which means a Martin Hall makeover, too. Page 6. WWW.UINDY.EDU 1 Portico Table of Contents 4 6 10 20 President’s forum UIndy launches Scholarly pursuits UIndy tapped The five-year plan to 5-year, $50-million Find out what’s happening to launch MBA accomplish the goals of development plan on campus this semester. in education Vision 2030, described on Investing in the University Plus, scholarships for UIndy has been chosen page 6, will have a dramatic and the neighborhood is children of the city’s fallen by the Woodrow Wilson impact on the University part of the plan to enhance public safety professionals. National Fellowship and the Southside. educational opportunities. Foundation to pilot an Curriculum and program 19 innovative master’s degree initiatives will sharpen in business—tailored for 5 Grant supports UIndy’s competitive edge. school leaders. $1-million city grant STEM teaching to support UIndy collaboration neighborhood 8 UIndy is one of just five 22 Indianapolis has bestowed Lugar and Nunn organizations nationwide to Green thumbs up $1 million on UIndy to help reflect, warn, receive a grant from the The Indy Food Fellows develop a health sciences and inspire Carnegie Corporation to program is letting UIndy center and improve a nearby “Diplomacy in a Dangerous foster collaboration with students play an integral role park (once the site of World,” a conversation with Dow AgroSciences to in improving the health of married student housing), Senate veterans Richard improve the preparation the local food system, while part of the effort to enhance Lugar and Sam Nunn of math teachers and the beefing up their résumés at programs and reinvigorate broadcast on PBS, packed academic performance of the same time.