Frayling, Sir Christopher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in London

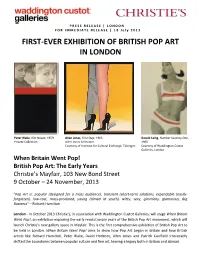

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 1 8 J u l y 2 0 1 3 FIRST- EVER EXHIBITION OF BRITISH POP ART IN LONDON Peter Blake, Kim Novak, 1959 Allen Jones, First Step, 1966 Gerald Laing, Number Seventy-One, Private Collection Allen Jones Collection 1965 Courtesy of Institute for Cultural Exchange, Tübingen Courtesy of Waddington Custot Galleries, London When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years Christie’s Mayfair, 103 New Bond Street 9 October – 24 November, 2013 "Pop Art is: popular (designed for a mass audience), transient (short-term solution), expendable (easily- forgotten), low-cost, mass-produced, young (aimed at youth), witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, Big Business" – Richard Hamilton London - In October 2013 Christie’s, in association with Waddington Custot Galleries, will stage When Britain Went Pop!, an exhibition exploring the early revolutionary years of the British Pop Art movement, which will launch Christie's new gallery space in Mayfair. This is the first comprehensive exhibition of British Pop Art to be held in London. When Britain Went Pop! aims to show how Pop Art began in Britain and how British artists like Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield irrevocably shifted the boundaries between popular culture and fine art, leaving a legacy both in Britain and abroad. British Pop Art was last explored in depth in the UK in 1991 as part of the Royal Academy’s survey exhibition of International Pop Art. This exhibition seeks to bring a fresh engagement with an influential movement long celebrated by collectors and museums alike, but many of whose artists have been overlooked in recent years. -

Art, Real Places, Better Than Real Places 1 Mark Pimlott

Art, real places, better than real places 1 Mark Pimlott 02 05 2013 Bluecoat Liverpool I/ Many years ago, toward the end of the 1980s, the architect Tony Fretton and I went on lots of walks, looking at ordinary buildings and interiors in London. When I say ordinary, they had appearances that could be described as fusing expediency, minimal composition and unconscious newness. The ‘unconscious’ modern architecture of the 1960s in the city were particularly interesting, as were places that were similarly, ‘unconsciously’ beautiful. We were the ones that were conscious of their raw, expressive beauty, and the basis of this beauty lay in the work of minimal and conceptual artists of that precious period between 1965 and 1975, particularly American artists, such as Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, Dan Flavin and Dan Graham. It was Tony who introduced (or re-introduced) me to these artists: I had a strong memory of Minimal Art from visits to the National Gallery in Ottawa, and works of Donald Judd, Claes Oldenburg and Richard Artschwager as a child. There was an aspect of directness, physicality, artistry and individualized or collective consciousness about this work that made it very exciting to us. This is the kind of architecture we wanted to make; and in my case, this is how I wanted to see, make pictures and make environments. To these ends, we made trips to see a lot of art, and art spaces, and the contemporary art spaces in Germany and Switzerland in particular held a special significance for us. I have to say that very few architects in Britain were doing this at the time, or looking at things the way we looked at them. -

Shock Value: the COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR?

Shock Value: THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? BY REENA JANA SHOCK VALUE: enough to prompt San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker to state, “I THE COLLECTOR AS PROVOCATEUR? don’t know another private collection as heavy on ‘shock art’ as Logan’s is.” When asked why his tastes veer toward the blatantly gory or overtly sexual, Logan doesn’t attempt to deny that he’s interested in shock art. But he does use predictably general terms to “defend” his collection, as if aware that such a collecting strategy may need a defense. “I have always sought out art that faces contemporary issues,” he says. “The nature of contemporary art is that it isn’t necessarily pretty.” In other words, collecting habits like Logan’s reflect the old idea of le bourgeoisie needing a little épatement. Logan likes to draw a line between his tastes and what he believes are those of the status quo. “The majority of people in general like to see pretty things when they think of what art should be. But I believe there is a better dialogue when work is unpretty,” he says. “To my mind, art doesn’t fulfill its function unless there’s ent Logan is burly, clean-cut a dialogue started.” 82 and grey-haired—the farthestK thing you could imagine from a gold-chain- Indeed, if shock art can be defined, it’s art that produces a visceral, 83 wearing sleazeball or a death-obsessed goth. In fact, the 57-year-old usually often unpleasant, reaction, a reaction that prompts people to talk, even if at sports a preppy coat and tie. -

Charles Saatchi's 'Newspeak'

Charles Saatchi’s ‘Newspeak’ By Jackie Wullschlager Published: June 4 2010 22:15 | Last updated: June 4 2010 22:15 Is Charles Saatchi having fun? On the plus side, he is the biggest private collector in Britain. His Chelsea gallery is among the most beautiful and well-appointed in the world. It is relaxed, impious, free, and full, which matters because, as Saatchi often admits, “I primarily buy art to show it off.” He buys whatever he likes, often on a whim: “the key is to have very wobbly taste.” Yet for all the flamboyance with which he presents his purchases, it is not clear that he is convinced by them. “By and large talent is in such short supply mediocrity can be taken for brilliance rather more than genius can go undiscovered,” he says, adding that when history edits the late 20th century, “every artist other than Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, Donald Judd and Damien Hirst will be a footnote.” These quotations come from a question-and-answer volume, My Name is Charles Saatchi and I am an Artoholic, published last autumn, and their tone of breezy disenchantment, combined with the insouciance with which his new show, Newspeak, is selected and curated, suggests that at 67 Saatchi is downgrading his game. After recent exhibitions concentrated on China, the Middle East, America and India, Newspeak It Happened In The Corner’ (2007) by Glasgow-based duo littlewhitehead returns to the territory with which he made his name as a collector in Sensation in 1997: young British artists. But whereas Sensation, tightly selected around curator Norman Rosenthal’s theme of a “new and radical attitude to realism” by artists including Hirst, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Rachel Whiteread, Marc Quinn, had a precise, powerful theme, Newspeak has a scatter-gun, unfocused approach. -

Visual Art in the English Parish Church Since 1945

Peter Webster Institute of Historical Research Visual art in the English parish church since 1945 [One of a series of short articles contributed to the DVD-ROM The English Parish Church (York, Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture, 2010).1] Even the most fleeting of tours of the English cathedrals in the present day would give an observer the impression that the Church of England was a major patron of contemporary art. Commissions, competitions and exhibitions abound; at the time of writing Chichester cathedral is in the process of commissioning a major new work, and the shortlist of artists includes figures of the stature of Mark Wallinger and Antony Gormley. It is less well known that this activity is in fact a relatively recent phenomenon. In the early 1930s, by contrast, it was widely thought (amongst those clergy, artists and critics who thought about such things) that there was, in the strictest sense, no art at all in English churches. Of course, the medieval cathedrals and parish churches contained many exquisite examples of the art of their time. The nineteenth century had seen a massive boom in urban church building in the revived Gothic style, with attendant furnishings and decoration. However, the vast bulk of the stained glass, ornaments and church plate of the more recent past was regarded as hopelessly derivative at best, and of poor workmanship at worst. The sculptor Henry Moore wrote of the ‘affected and sentimental prettiness’ of much of the church art of his time. One director of the Tate Gallery argued that if the contents of churches were the only evidence available, ‘our civilisation would be found shallow, vulgar, timid and complacent, the meanest there has ever been.’ Much research remains to be done on that nineteenth century heritage, to determine how justly such charges were laid against it. -

R.B. Kitaj: Obsessions

PRESS RELEASE 2012 R.B. Kitaj: Obsessions The Art of Identity (21 Feb - 16 June 2013) Jewish Museum London Analyst for Our Time (23 Feb - 16 June 2013) Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, West Sussex A major retrospective exhibition of the work of R. B. R.B. Kitaj, Juan de la Cruz, 1967, Oil on canvas, Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo; If Not, Not, 1975, Oil and black chalk on canvas, Scottish Kitaj (1932-2007) - one of the most significant National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh © R.B. Kitaj Estate. painters of the post-war period – displayed concurrently in two major venues for its only UK showing. Later he enrolled at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, and then, in 1959, he went to the Royal College of Art in This international touring show is the first major London, where he was a contemporary of artists such as retrospective exhibition in the UK since the artist’s Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney, the latter of whom controversial Tate show in the mid-1990s and the first remained his closest painter friend throughout his life. comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s oeuvre since his death in 2007. Comprised of more than 70 works, R.B. During the 1960s Kitaj, together with his friends Francis Kitaj: Obsessions comes to the UK from the Jewish Museum Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud were Berlin and will be shown concurrently at Pallant House instrumental in pioneering a new, figurative art which defied Gallery, Chichester and the Jewish Museum London. the trend in abstraction and conceptualism. -

New Self-Portrait by Howard Hodgkin Takes Centre Stage in National Portrait Gallery Exhibition

News Release Wednesday 22 March 2017 NEW SELF-PORTRAIT BY HOWARD HODGKIN TAKES CENTRE STAGE IN NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY EXHIBITION Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends, 23 March – 18 June 2017 National Portrait Gallery, London Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music by Howard Hodgkin, 2011-2016, Courtesy Gagosian © Howard Hodgkin; Portrait of the artist by Miriam Perez. Courtesy Gagosian. A recently completed self-portrait by the late Howard Hodgkin (1932-2017) will go on public display for the first time in a major new exhibition, Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends, at the National Portrait Gallery, London. Portrait of the Artist Listening to Music was completed by Hodgkin in late 2016 with the National Portrait Gallery exhibition in mind. The large oil on wood painting, (1860mm x 2630mm) is Hodgkin’s last major painting, and evokes a deeply personal situation in which the act of remembering is memorialised in paint. While Hodgkin worked on it, recordings of two pieces of music were played continuously: ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’ composed by Jerome Kern and published in 1940, and the zither music from the 1949 film The Third Man, composed and performed by Anton Karas. Both pieces were favourites of the artist and closely linked with earlier times in his life that the experience of listening recalled. Kern’s song is itself a meditation on looking back and reliving the past. Also exhibited for the first time are early drawings from Hodgkin’s private collection, made while he was studying at Bath Academy of Art, Corsham in the 1950s. While very few works survive from this formative period in Hodgkin’s career, the drawings of a fellow student, Blondie, his landlady Miss Spackman and Two Women at a Table, exemplify key characteristics of Hodgkin’s approach which continued throughout his career. -

'Champing, Crawlers and Heavenly Cafes'

‘Champing, Crawlers and Heavenly Cafes’ Can Sussex Churches make more of the Visitor Economy ? Nigel Smith Chief Executive Tourism South East www.tourismsoutheast.com Tourism South East Tourism South East………. - is a not-for-profit member and partnership organisation - ‘Provides services and expertise to support the performance and growth of tourism businesses and destinations.’ - primarily covers Hants, IoW, Sussex, Kent, Surrey, Berks, Bucks and Oxon – but delivers UK wide. - offers marketing, training, research, visitor information, consultancy and advocacy services and the Beautiful South Awards www.tourismsoutheast.com Tourism South East Cathedral and Church Members Guildford Cathedral Winchester Cathedral Chichester Cathedral Canterbury Cathedral Rochester Cathedral Churches Conservation Trust St Mary’s, Itchen Stoke, Hampshire All Saints, Nuneham Courteney, Oxfordshire St Bartholomew’s, Lower Basildon, Berks St Peter’s, Sandwich, Kent St Mary’s Pitstone, Bucks St Peter and St Paul, Albury, Surrey St Peter’s, Preston Park, Sussex www.tourismsoutheast.com Economic Value of the Visitor Economy in the South East • Worth £12+ billion • Supports 400,000 jobs • Larger than Scotland and Wales put together….. www.tourismsoutheast.com Economic Value of the Visitor Economy in Sussex • West Sussex 2016 £1.0 billion • East Sussex 2016 £1.5 billion • Brighton & Hove 2016 £0.85 billion Total £3. 35 billion www.tourismsoutheast.com Visitors to Sussex - Domestic overnight stays are mostly ABC1(69%), adult couples on short breaks - Family Groups account for 35% of staying visitors - Over 80% are on holiday for pleasure - Over 40% stay with or are with VFR - Over half stay in ‘seaside’ locations and 21% in countryside locations - Visits to cultural and heritage attractions and events are significant for both staying and day visitors - International visitors are mostly from Nr Europe with nearly half arriving via Gatwick or Heathrow www.tourismsoutheast.com Churches What do we know? • Est. -

A View from the Archives of Durham, St Paul's, and York Minster

Cathedral music and the First World War: A view from the Archives of Durham, St Paul’s, and York Minster Enya Helen Lauren Doyle Master of Arts (by research) University of York Music July 2016 Abstract This thesis explores the impact of the First World War on English Cathedral music, both during the long four years and in its aftermath. Throughout this study, reference will be made specifically to three English cathedrals: York Minster, Durham and St Paul’s. The examination will be carried out chronologically, in three parts: before the war (part one), during the war (part two) and after the war (part three). Each of these three parts consists of two chapters. Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 help to set the scene and offer context. In chapters 2- 5 there is a more focused and systematic investigation into the day-to-day administrative challenges that the Cathedrals faced, followed in each chapter by an assessment of the musical programme. Chapter 6 examines the long-term impact of the war on British cathedral music, especially in the centenary anniversary years. The Great War is often perceived as a complete break with the past, yet it also represented an imaginative continuity of sorts. As such, 1914-18 can be seen as a period of twilight in a lot of senses. The war managed to bring the flirtation with modernism, which was undoubtedly happening at the beginning of the century, to at least a temporary halt. Through the examination of the archives of the three cathedrals, this thesis investigates how the world war left its mark on the musical life of this portion of English religious and music life, during and after the war, drawing national comparisons as well as showing the particulars of each cathedral. -

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

Plate 6 Epiphany by Marcus a Vincent 195641956 Oil on Panel 515111 X 20 1989 Courtesy Museum of Church History and Art

plate 6 epiphany by marcus A vincent 195641956 oil on panel 515111 x 20 1989 courtesy museum of church history and art A woman in a moment of silent enlightenment begins to understand an eternal truth vincent paints the woman realisti- cally juxtaposing her mortality against an abstract background symbolizing the world of the spirit the paradox of silence in the arts and religion through paradoxical silences some artists convey their an- guish over heavens unresponsiveness in theracethefacethe facehace of evil but in religion silence often conveys gods presence and sorrow jon D green only by the form the pattern can words or music reach the stillness as a chinese jar still moves perpetually in its stillness T S eliot four quartets introduction T S eliotseliote stanza captures an essential ingredient in the theme of this essay the paradoxical relationship between the mute and the immutable between silence and stasis the jar is still silent and unmoving yet still moves us in its stillness qui- etude the word still suggests that both the mute and the motion- less have continuous being and silence is laden with messages that reach our emotions the simple paradox of silence is that what is not said can be more expressive than what is said this paradox of silence has universal applications in every culture and civilization silence weaves its way through gods com- municationmunication with his creations and throughout our attempt to communicate with the divine and with each other particularly through the arts for the purposes of this paper I1 -

Gagosian Gallery

Financial Times January 20, 2020 GAGOSIAN Living with Damien Hirst and friends Robert Tibbles was an early collector of the Young British Artists — now he is preparing to sell many of his acquisitions Melanie Gerlis Caption (TNR 9 Italicized) Everyone likes to say that they discovered an artist before they were famous, but in the case of the London bond salesman Robert Tibbles, the claim is true. Back in the 1980s, the late art dealer Karsten Schubert introduced Tibbles to the work of an art student called Damien Hirst. Alongside Charles Saatchi, Tibbles then became one of the now-superstar artist’s first buyers. So began an intense, 15-year collecting spree, mostly of works by Hirst and other Young British Artists. These now dominate Tibbles’s Victorian ground-floor flat in London’s leafy Kensington, where an early Hirst spot painting, “Antipyrylazo III” (1994), has loomed almost too large over the living room fireplace since Tibbles bought it in the year it was made. Hanging nearby is another early purchase — Hirst’s degree-show medicine cabinet “Bodies” (1989) — a work that demonstrates Tibbles’s aptitude for picking the right time in the art market as well as the debt markets. He bought the cabinet for £600 (again, in the year it was made) and now, as Tibbles prepares to sell much of his YBA collection at auction at Phillips in London, the cabinet is valued between £1.2m and £1.8m. “There’s no question that the medicine cabinet and other works were not liked or understood by many of my friends.