Infrastructure Strategy 2018-2048

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Article

Quarterly Bulletin of The Ornithological Society of New Zealand Volume 7, Number Seven :January l 958 NOTORNIS In continuation of New Zealand Bird Notes BULLETIN OP THE ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ZBALAND (Incorporated) Registered with the G.P.O., Wellington, as a Magazine Edited by R. B. SIBSON, King's College, Auckland S.E.7 Annual Subscription, 10/- (Juniors, 5/-); Endowment Membership, Cl; Life Membership, E10 (for members over thirty years of age). OFFICERS, 1957 - 58 President - MR P. C. BULL, Lower Hutt. North Island Vice-President - MR E. G. TURBOTT, Christchurcb South Island Vice-President - MRS L. E. WALKER, Dunedin Editor- MR R. B. SIBSON, King's College, Auckland S.E.7 Treasurer - MR H. R. McKENZIE, North Road, Clevedon Secretary - MR G. R. WILLIAMS, Wildlife Division, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington MRS 0. SANSOM, Invercargill; DR R. A. FALLA, Wellington; MR J. C. DAVENPORT, Auckland Contents of Volume 7, Number 7 : January 1958 Some Notes on Muttonbirding in the North Island- W. J. Phillipps 189 Classified Summarised Notes .................................... 191 Annual Locality Reports for Firth of Thames and Manukau Harbour 201 Obituary: W. R. B. Oliver ....................................205 Short Notes mentioning: S.I. Pied Oystercatcher, White-faced Heron, Spotted Shag, Barn Owl, Spur-winged Plover, Crested Grebe, 'Red- legged ' Herons, Myna in !;.I., Bush-hawk, Weka ................ 206 Review8 .................................................... 2 11 Notices. XIIth International Ornithological Congress ............ 212 Nest Records Scherne Publications for sale Donations NOTORNI S VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER SEVEN : JANUARY NINETEEN FIFTY-EIGHT SOME NOTES ON MUTTONBIRDIING IN THE NORTH ISLAND By W. 1. PHILLIPPS During the period 1919- 1924 odd notes were collected on the occurrence of muttonbirds breeding on Mount Pihanga not far from Lake Rotoaira. -

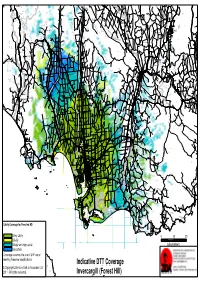

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197

SECTION 6 SCHEDULES Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197 SECTION 6: SCHEDULES SCHEDULE SUBJECT MATTER RELEVANT SECTION PAGE 6.1 Designations and Requirements 3.13 Public Works 199 6.2 Reserves 208 6.3 Rivers and Streams requiring Esplanade Mechanisms 3.7 Financial and Reserve 215 Requirements 6.4 Roading Hierarchy 3.2 Transportation 217 6.5 Design Vehicles 3.2 Transportation 221 6.6 Parking and Access Layouts 3.2 Transportation 213 6.7 Vehicle Parking Requirements 3.2 Transportation 227 6.8 Archaeological Sites 3.4 Heritage 228 6.9 Registered Historic Buildings, Places and Sites 3.4 Heritage 251 6.10 Local Historic Significance (Unregistered) 3.4 Heritage 253 6.11 Sites of Natural or Unique Significance 3.4 Heritage 254 6.12 Significant Tree and Bush Stands 3.4 Heritage 255 6.13 Significant Geological Sites and Landforms 3.4 Heritage 258 6.14 Significant Wetland and Wildlife Habitats 3.4 Heritage 274 6.15 Amalgamated with Schedule 6.14 277 6.16 Information Requirements for Resource Consent 2.2 The Planning Process 278 Applications 6.17 Guidelines for Signs 4.5 Urban Resource Area 281 6.18 Airport Approach Vectors 3.2 Transportation 283 6.19 Waterbody Speed Limits and Reserved Areas 3.5 Water 284 6.20 Reserve Development Programme 3.7 Financial and Reserve 286 Requirements 6.21 Railway Sight Lines 3.2 Transportation 287 6.22 Edendale Dairy Plant Development Concept Plan 288 6.23 Stewart Island Industrial Area Concept Plan 293 6.24 Wilding Trees Maps 295 6.25 Te Anau Residential Zone B 298 6.26 Eweburn Resource Area 301 Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 198 6.1 DESIGNATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS This Schedule cross references with Section 3.13 at Page 124 Desig. -

The New Zealand Gazette 1489

5 ,SEPTEMBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1489 Allenton- Onetangi, Community Hall. Creek Road Hall. Ostend, First Aid Room. School. Palm Beach, Domain Hall. Anama School. Rocky Bay, Omiha Hall. Arundel School. Surfdale, Surfdale Hall. Ashburton- Borough Chambers. College, Junior Division, Cameron Street. College, Senior DiviSIon, Cass Street. Courthouse. Hampstead School, Wellington Street. Burkes Pass Public Hall. Avon Electoral District Carew School. Aranui- Cave Public Hall. Public School, Breezes Road. Chamberlain (Albury), Coal Mine Road Comer, Mr M. A. St. James School, Rowan Avenue. Fraser's House. Bromley Public School. Clandeboye School. Burwood- Coldstream, Mr Studholmes Whare. Brethren Sunday School, Bassett Street. Cricklewood Public Hall. Cresswell Motors Garage, New Brighton Road. Ealing Public Hall. Public School, New Brighton Road. Eiffelton SchooL Dallington Anglican Sunday School, Gayhurst Road. Fairlie Courthouse. Linwood North Public School, Woodham Road. Flemington SchooL New Brighton- Gapes Valley Public Hall. Central School, Seaview Road. Geraldine- Freeville Public School, Sandy Avenue. Borough Chambers. Garage, corner Union and Rodney Streets. Variety Trading Co., Talbot Street. North Beach Methodist Church Hall, Marriotts Road. Greenstreet Hall. North New Brighton- Hermitage, Mount Cook, Wakefield Cottage. Peace Memorial Hall, Marine Parade. Hilton SchooL Public School, Leaver Terrace. Hinds SchooL Sandilands Garage, 9 Coulter Street. Kakahu Bush Public Hall. Shirley- Kimbell Old School Building. Garage, 40 Vardon Crescent. Lake Pukaki SchooL Public School, Banks Avenue. Lismore SchooL Rowe Memorial Hall, North Parade. Lowc1iffe SchooL South New Brighton- Maronan Road Hall. Garage, 1 Caspian Street. Mayfield School. Public School, Estuary Road. Milford School. Wainoni- Montalto SchooL Avondale Primary School, Breezes Road. Mount Nessing (Albury) Public Hall. -

Bio of Catherine MOLLOY

Biographical Outline of the Life of Catherine MOLLOY and the McFEELY Family Date Event and Place Documentation Jan 1861 Baptism Carragh, County Baptism Record Kildare, Ireland 26 Jan 1864 Arrived at Bluff, Southland Southland Times. Volume lll, Issue on the “Edward Thornhill” 37 1st Feb 1864, page 4. from London with her parents and 2 brothers. 1872 Gropers Bush School Book: Records of Early Riverton opened. Catherine was and District enrolled 31 Mar 1880 Marriage to Dennis Marriage Certificate McFEELY at Caledonian Hotel, Riverton, NZ. Mar 1881 Daughter Margaret born Riverton burial records 25 May 1881 Margaret died aged 2 Riverton burial records months and was buried in Riverton cemetery 11 Sep 1882 A stillborn baby born. Buried Riverton burial records in Riverton Cemetery. 10 Sep 1883 Daughter Mary Jane born at Riverton, Southland, New Zealand. 26 Dec 1885 A stillborn baby born. Buried Riverton burial records in Riverton Cemetery. 27 Nov 1886 Son Hugh born Otautau, Southland, NZ 31 May 1888 A stillborn baby born. Buried Riverton burial records in Riverton Cemetery. 1889 Son William Denis born in Australian Birth Index Victoria, Australia. 1890 William Denis died in Australian Death Index Northcote, Vic, Aus aged 1 year 6 months. May/Jun 1893 Daughter Catherine born Australian Birth Index 3 Jul1893 Death of Catherine Molloy at Victorian Death Certificate Margaret St, Footscray, Victoria, Australia 1893 Children Hugh and Mary Kiwi Index enrolled at Gummies Bush School, Southland, NZ 1903 Dennis is living at Gold Electoral Roll Blocks, WA. occupation Miner 12 Dec 1904 Death of Dennis McFeely in Australian Death Index Western Australia aged 45. -

The New Zealand Gazette 2145

29 OCTOBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 2145 Rothesay Bay Brydone, Public School. Methodist Church Hall. Castlerock, F. W. Thomas's Woolshed. Public Hall. Charlton, Public Hall. Swanson, Public School. Clifden, Public School. Taupak,i, Public Hall. Colac Bay, Public School. Torbay, Ptresbyterian Sunday School Hall. Dipton, Public School. Waiake, Methodist Church Hall. Drummond, Public School. Waitakere, Public School. Dunearn, Public School. Whenuapai- Eastern Bush, Public School. Public School. Fairfax, Public School. Village Hall. Ferndale, Public School. Five Rivers, Public School. Garston, Public School. Glenary, Old School. Waitomo Electoral District- Glencoe, Public Hall. Aria, Public School. Gummies Bush, Public Hall. Arohena, Public School. Hamilton Burn, R. A. Heenan's Residence. Benneydale, Hall, Library Room. Heddon Bush, Public School. Hairini, Public Hall. Hedgehope, Public School. Hangatiki, Public School; Hokonui, Public School. Hauturu, Public School. Isla Bank, Public School. Honikiwi, Public School. Kauana, Public School. Kaipaki, Public School. Kingston, Public School. Kailrangi, Public Hall. Limehills, Public School. Kawhia, Community Hall. Lora Gorge, Public School. Kihikihi, Town Hall. Lumsden, Public School. Kinohaku, Public Hall. Manapouri, Public School. Kiokio, Public School. Mandeville, Public School. Kopaki, Public School. Mararoa, Public School. Korakonui, Public School. Mataura- Mahoenui, Memorial Hall. Council Chambers. Maihiihi, Public School. Public School. Mairoa, Public Hall. Merrivale, Public School. Mangapehi, Public School. Monowai, Social Hall. Mangapiko, Public Hall. Mossburn, Public School. Mapiu, Public School. Nightcaps, Public School. Marokopa, Public School. Ohai, Public School. Mokauiti, Public School. Opio, Public Hall. Monavale, Public Hall. Orawia, Public School. Ngahape, Public Hall. Orepuki, Public School. Ngaroma, Public School. Oreti Plains, Public School. Ngatamahine, Community Centre Hall. Otama, Public School. -

Compliance Monitoring Report

Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report 2006/07 Report by - Environment Southland Compliance Division Environment Southland Publication No 2007/09 Environment Southland is the brand name of the Southland Regional Council In the 2004/05 Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report it was reported that an Abatement Notice was issued to Mr Peter James Hargest. This was incorrect. No Abatement Notice was issued by Environment Southland against Mr Hargest. Council apologise for this mistake. The Council’s Compliance Manager has personally contacted Mr Hargest and has changed the way Abatement Notices are processed, so that this mistake cannot occur again. Foreword The Compliance Division provides a 24 hour, 365 day response to public complaints involving matters pertaining to our environment. Due to good publicity and education by Environment Southland, it is agreed that the public now has a much better understanding of what is or is not acceptable when it comes to environmental issues. It is quite clear that the public will no longer tolerate the adverse actions of environmental vandals. Public awareness has undoubtedly contributed to a 40% increase in complaints directed to this division this year. Under the management of Mark Hunter, our dedicated Compliance staff have worked well to keep on top of all issues. A testing time was recently had with odour problems at the Clifton Wastewater Treatment Plant. Pressure was put on the Invercargill City Council to act and address the issues affecting the Clifton residents, and we are now hopeful that this matter has been resolved. The Coastal Plan has now become operative and a new staff member has been appointed to assist with the implementation of this plan. -

Groundwater Provisions of the Proposed Southland Land And

Groundwater Provisions of the Proposed Southland Water and Land Plan Technical background June 2017 Prepared By: For any information regarding this report please contact: Brydon Hughes Phone: 021 495 229 or 03 310 7420 Email: [email protected] Land Water People Ltd PO Box 70 Lyttelton 8092 New Zealand LWP Client Report Number: LWP17063 Report Date: June 2017 LWP Project: Quality Assurance Statement Version Reviewed By Version 1 Karen Wilson Document History Version Date Status: Description Draft 30/6/2017 Draft Draft for client review Final 4/7/2017 Final Page 2 of 88 Table of Contents 1 Background ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 1.1.1 Report Scope ................................................................................. 4 2 Existing groundwater management framework .............................................. 5 2.1 Regional Water Plan .................................................................................. 5 2.1.1 Southland Water Resources Study ................................................. 5 2.2 Variation 3 ................................................................................................. 6 2.3 Variation 12 ............................................................................................... 7 3 Groundwater provisions of the Proposed Southland Water and Land Plan . 9 3.1 Groundwater Abstraction -

THE NEW ZEALAND- GAZETTE. [No

-3148 THE NEW ZEALAND- GAZETTE. [No. 113 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-oon,tinued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILLf-0011..tin'Uied: 520350 Hamilton, William Duncan, carrier, 47 McMaster St. 589094 Henderson; John Gibb, company secretary, Bridport 579092 Hankey, Fr.ank, farmer, Waihola. St,. Kaitangata. 538827 Hankey, Hans Charles, farmer, Pukerau. 520200 Henderson, John Wood, engineer, 176 George St. 499469 :ij:annah, Archibald Douglas, engine-driver, Clinton. 520199 Henderson, Kenneth, engine-driver, 131 Panton St. 514954 Hanning, Robert Douglas, fisherman, Blackwater St., 521214 Henderson, Peter Edward, farmer, Otapiri R.D. Bluff. 553119 Henderson, Robert Nathan, farmer, Otapiri R.D., 540985 Hans,en, Harry Mars, coal-miner, Clyde Tee., Kai- Winton. tangata. 569884 Henderson, William Evans, farmer, Otapiri R.D., 607 440 Hansen, James Barron, labourer, Dryden St., Milton. Winton. 634451 Hansen, Richard Charles, farm labourer, Mokotua. 469967 Henderson, William John, manager, Roxburgh. 611641 Hansen, Theodore Archibald, . sawmill employ~, 534001 Henley, Stafford James, slaughterman, 210 Liddel St. Tawanui. 492703 Herbison, Robert Coleman, farmer, c/o Post-office, 506123 Hardie, Peter, labourer, 218 Foyle St., Bluff. Wreys Bush. 552793 Hardiman, James William, carpenter, 139 St. Andrew St. 634378 Herron, John Thompson, apiarist's assistant, Gore 542416 Hardy, James Leonard, butcher, Tanner St., Grassmen~. Wa\ikruka R.D., Gore. 506131 Hardy, John, lorry-driver, 45 Ramrig St. 582758 Herron, Joseph Clyde, farmer, Waikaka R.D., Gore. 622510 Hardy, Thomas Vincent,· farmer, Post-office, Morton 540577 Herron:,· William Thompson, apiarist, Waikaka R.D., Mains. Gore. 542424 Hare, Alfred Roland, labourer,· Moore St., Milton. 542598 Hewett, Charles George, farm labourer, Waikaka R.D., 517867 Hare, William, labourer, Milburn. -

Water Supply Activity

Executive summary .......................................................................................................................... 8 Financial summary ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Purpose of the activity management plan ........................................................................................ 11 Plan limitations ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Plan framework ...................................................................................................................................................... 12 Activity description ........................................................................................................................... 13 Purpose of this Plan .............................................................................................................................................. 13 What we do ............................................................................................................................................................. 13 Urban and rural areas serviced by public water supplies ............................................................................. 13 Rural areas and isolated towns ........................................................................................................................ 14 -

TRE NEW Zeatan'd GAZETTE. [N'o

2550 TRE NEW ZEAtAN'D GAZETTE. [N'o. 101 411731 Eedy, George Samuel, Farmer, Section 1, Otahuti Rural 091345 Goodwin, Lindsay Keith, Chainman, care of Geodetic Delivery. Survey, Riverdale, Southland. 031021 Ellenden, Elvin, Radio Operator, Awarua Radio Private 295368 Gordon, Charles Ronald, Farm Hand, Garston. Bag, I vercargill. 317472 Gordon, Irvine, Farmer, "Oakleigh," Heriot. 264410 English, John, Labourer, Main St, Mataura, Southland. 235335 Gordon, Thomas James, Farm Hand, Carteret St, Mataura. 307623 English, William Henry, Salesman, care of Andrews and 247025 Gosden, Allan Lester, Cadet, Post and Telegraph Depart- Beaven, Ltd., Dee St, lnvercargill•. ment, Tapanui. 426234 Enright, William Gerald, Farmer, Kapuka, Invercargill. 405264 Gosney, Andrew Lawrence, Draughtsman, Public Works 410920 Erskine, William Alexander, Dairy-farmer, Gummies Bush, Department, Haast Pass Rd, via Pembroke. lnvercargill. 153103 Goudie, Kenneth Alexander, Plantation Foreman, State 008812 Evans, Jack, Farm Hand, Crookston Rural Delivery, Forest Service, Conical Hill, via W aipahi. Heriot Post-office. 411710 Gow, Alexander Erskine, Farmer, Waikara Rural Delivery 1, 270836 Evans, Leslie Gordon, Packer, care of Mr. Capon, Fruit. Gore. grower, Roxburgh. 295011 Graham, William Russell, Clerk, 144 Esk St, lnvercargill. 289159 Ewan, Kenneth Gordon, Farm Hand, Glenhal!l, 266553 Graham, William Samuel, Farmer, Waipahi. 290998 Fahey, Leonard Patrick, Labourer, Lawrence. 262220 Grant, Ian Melville, 9 Ramrig St, Invercargill. 229890 Fairbairn, Ian Samuel, Farm Hand, Rennington. 264417 Grant, James Alfred, Apprentice Engineer, Culling Terrace, 397006 Fairbairn, Robert Maurice, Section 3, Invercargill, Glencoe Mataura. Rural Delivery. 277536 Grant, Norman James, Miner, Box 10, Nightcaps. 137559 Falconer, Charles Alister, Farmer, Morton Maine. 408923 Grant, Osborne Wallace, Miner, Nightcaps. 302471 Feichley, William, Boner, Main St, Mataura. -

10 Novrunrn TIIE NEW ZEALAND GANTTE 2519

10 Novrunrn TIIE NEW ZEALAND GANTTE 2519 Wallace Electoral District- Castlecliff- Aparima, Public Hall. Aranui Avenue, Aranui Public School. Athol, Public School. Manuka Street, St Luke's Anglican Church Hall. Balfour. Public School. Matipo Street, Kokohuia Public School. Birchrvood, Mount Linton Station Cookohop. Polson Street, Public School. Blackmount, Public School. Dublin Street, Wanganui Interrnediate School. Browns, Public School. Durie Hill, Portal Street, Public School. Brydone, Public School. Gloucester Street, St Andrew's Presbyterian Schoolroom. Castlerock, F. W. Thomasb Rcsidencs. Gonville- Charlton. Public Hall. Gonville Avenue, Gonville Public School. Clifden, Public School. Heads Road, General Hospital. Colac Bay, Public School. Swiss Avenue, Scout Hall. Dipton, Public School. Totara Street, Tawhero Public School. Drummond, Public School. Guyton Street, Railway Social Hall. Dunearn, Public School. Keith Street, Public School. Eastern Bush, Public School. Market Place, Courthouse. Fairfax, Public School. Maria Place, Wanganui Prison. Ferndale, Public School. St John's Hill, Parkes Avenue, Public School. Five fuvers, Public School. Springvale, Fox Road, Scout Hall. Garston, Public School. Upper Aramoho, Burmah Street, Churton Public School. Glenary, Old School. Wanganui East- Glencoe, Public Hall. Kawakawa Street, Wanganui East Kindergarrten, Gore, Courthouse. Kiwi Street, Kiwi Street Public School. - Gummies Bush, Public llall. Tinirau Street, Wanganui East Public School. Hamilton Burn, R. A. Heenan's Residence. Heddon Bush. Public School. Hedgehope, Public School. Hokonui, Public School. Isla Bank. Public School. Kauana, Public School. Wellington Central Electoral District- Kingston, Public School. City- Limehills. Public School. Aro Street, Matauranga School Hall, Lochiel, Public School. Brougham and Elizabeth Streets, Clyde Quay Schml. Lumsden, Public School. Cuba Street, Main Town Hall. Manapouri, Public School.