Grassroots Activism and Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Inquiry Into the Politics of Rural Water Allocations in Victoria

Watershed or Water Shared? An Inquiry into the Politics of Rural Water Allocations in Victoria Submitted in fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Barry Hancock May 2010 Well, you see Willard … In this war, things get confused out there - power, ideals, the old morality and practical military necessity. Out there with these natives it must be a temptation to be good because there's a conflict in every human heart between the rational and the irrational, between good and evil. The good does not always triumph. Sometimes the dark side overcomes what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature. Every man has got a breaking point – both you and I have. Walter Kurtz has reached his. And very obviously, he has gone insane (Apocalypse Now). ii Abstract This thesis explores the politics associated with rural water reform in Victoria. The specific focus of the thesis is on the period from 1980 through to the time of submission in May 2010. During this period, the rural water sector has undergone radical reform in Victoria. Initially, reforms were driven by a desire to improve the operational efficiency of the State’s rural water sector. With the growing realisation that water extractions were pressing against the limits of sustainable yield, the focus of the reform agenda shifted to increasing the economic efficiency derived from every megalitre of water. By early 2000, the focus of the rural water reform changed as prolonged drought impacted on the reliability of water supply for the irrigation community. The objective of the latest round of reforms was to improve the efficiency of water usage as the scarcity became more acute. -

Assembly December Weekly Book 1 2006

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 1 19 and 20 December 2006 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs.............................................. The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Water, Environment and Climate Change...................................................... The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Skills, Education Services and Employment and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Gaming, Minister for Consumer Affairs and Minister assisting the Premier on Multicultural Affairs ..................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Victorian Communities and Minister for Energy and Resources.................................................... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Treasurer, Minister for Regional and Rural Development and Minister for Innovation......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Agriculture.......................................... -

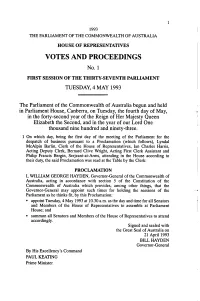

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1993 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 4 MAY 1993 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the fourth day of May, in the forty-second year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and ninety-three. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (which follows), Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Ian Charles Harris, Acting Deputy Clerk, Bernard Clive Wright, Acting First Clerk Assistant and Philip Francis Bergin, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION I, WILLIAM GEORGE HAYDEN, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting in accordance with section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia which provides, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, by this Proclamation: " appoint Tuesday, 4 May 1993 at 10.30 a.m. as the day and time for all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to assemble at Parliament House; and * summon all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to attend accordingly. Signed and sealed with the Great Seal of Australia on 21 April 1993 BILL HAYDEN Governor-General By His Excellency's Command PAUL KEATING Prime Minister No. -

Aston (LIB 7.6%)

Aston (LIB 7.6%) Location Eastern Suburbs of Melbourne. Aston includes the suburbs of Bayswater, Boronia, Scoresby, Ferntree Gully and Rowville. State electorates within Aston: All of Ferntree Gully (Lib), parts of Bayswater (ALP), Rowville (Lib) and Monbulk (ALP). Redistribution Gains parts of Boronia, Ferntree Gully and The Basin from La Trobe, reducing the Liberal margin from 8.6% to 7.6% History Aston was created in 1984. Its first member was Labor’s John Saunderson who held it until he was defeated in 1990 by the Liberal Party’s Peter Nugent and it has stayed in Liberal hands ever since. Nugent was MP until his death in 2001 and was succeeded at the by election by Chris Pearce (The Aston by-election has been regarded as the moment where John Howard turned around his electoral fortunes). Pearce was a parliamentary secretary in the last term of the Howard Government and was Shadow Financial Services Minister during Turnbull’s first stint as leader before being dumped by Abbott. He retired in 2010 and was succeeded by Alan Tudge. Candidates Alan Tudge- LIB: Before his election, Tudge worked for the Boston Consulting group before becoming an adviser on education and foreign policy for the Howard Government and, subsequently, running his own policy advisory firm. Tudge was appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister before being promoted in 2015 by Malcolm Turnbull to the front bench as Minister for Human Services, he held this portfolio until December 2017 when he was made Minister for Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs. He is currently the Minister for Cities, having been appointed to this position when Scott Morrison became prime minister. -

7 October 1993 ASSEMBLY 1019

LAND (FURTHER AMENDMENT) BILL Thursday, 7 October 1993 ASSEMBLY 1019 was being exceedingly ill mannered. I am entitled to Mr DOLUS (Richmond) - I also suggest that the make that point, and it stands. Bill be withdrawn. As the shadow Treasurer stated, the opposition does not oppose the objectives of the The Minister has taken unto himself the divine right Bill. It understands the necessity for the Bill, but it to resolve those issues. Nowhere in public policy has a number of concerns about whether the legal making is that considered to be appropriate. The rights of the Melbourne Central walkway could Minister has also taken unto himself - the language create a number of issues that Parliament may have he uses in his second-reading speech is particularly to deal with at some time in the future. interesting - the right to get rid of compensation claims. There is no provision for members who feel Has the Minister for Finance received advice from aggrieved or injured and whose interests have been his colleague, the Minister for Planning, about the set aside or adversely affected to pick up effects of the Bill on the planning powers in this compensation. In his second-reading speech, the State? Will Ministerial powers contained in the Bill Minister makes the following point: override the powers in the Planning and Environment Act? The Minister is not paying The Bill also inserts into the Land Act 1958 proposed attention to my contribution. I wonder whether the section 412, which section alters or varies section 85 of Minister - hello! I am trying to ask the Minister a the Constitution Act 1975 to the extent necessary to fundamental question. -

The Celebrated Contest Over Indi and the Fate of the Independents

16. The Contest for Rural Representation: The celebrated contest over Indi and the fate of the independents Jennifer Curtin and Brian Costar Over the past decade, independent parliamentarians have become a recurring feature of Australian federal politics (and elsewhere). This has sparked speculation about the extent to which independents represent a permanent challenge to the stability of two-party-dominant systems, both in Australia and internationally.1 At the state level, independents have regularly held the balance of power and federally, in the Senate, there have been occasions when independents as well as minor parties have shared the title of power broker. Consequently, over the past 20 years there has been occasional scholarly debate over whether the vote for ‘other’ parties represents a fragmentation of the two-party system and a decline in the strength of party identification as a key determinant of voting behaviour.2 Yet survey data still tell us that around 80 per cent of voters continue to identify as either Labor or Liberal and such loyalty sets Australia apart from many of its contemporaries (Bean and McAllister 2012). This suggests that independents may indeed be just a passing phase for momentarily disaffected voters. Yet the historic hung parliament election of 2010 ensured independents took centre stage in a way not seen federally since 1940. Although the percentage of party identifiers remained solid in 2010, with the combined primary vote for the Labor and the Coalition parties at 81 per cent and only 2.5 per cent of voters opting for independents (Brent 2013), support for the latter was sufficiently concentrated in key electorates to return three sitting rural independents (Bob Katter, Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor) and elect one other from Tasmania (Andrew Wilkie). -

Chapter 1 Introduction

The Growth and Development of Albury-Wodonga 1972-2006: United and Divided. Clara Stein B. A. (Wits.) M. A. (Macquarie). Department of Environment and Geography, Science Faculty, Macquarie University. This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Macquarie University 30 May 2012 i Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction Chapter 2 Spatial Concentration, Regionalism and Regional Development Spatial location theories. Political economy of regions. New Regionalism. Research Methodology. Conclusion. Chapter 3 Borders, theory and reality The border, territoriality and sovereignty, internal borders. Albury-Wodonga and the New South Wales and Victorian border. Conclusion. Chapter 4 History of regional policies The Golden Age. Regional policy during the Long Boom. AWDC and the Fraser government after 1975. Regional policy during the restructuring of the Australian economy. The demise of the AWDC. Regional policy during the return to prosperity. Conclusion. Chapter 5 Economic Development of Albury-Wodonga The Long Boom. The lead up to and restructuring of the Australian economy. The return top prosperity. Conclusion. ii Chapter 6 Anomalies Definition. Responses to anomalies Conclusion. Chapter 7 Business on the border Questionnaire. Manufacturing firms. Service firms. Conclusion. Chapter 8 Living along the Albury-Wodonga border The changing demographic profile of Albury-Wodonga. The Growth Centre and the AWDC. Community Action. Anomalies. Conclusion. Chapter 9 Conclusion The growth and development of Albury-Wodonga. Reflections on research. Research in the future. Bibliography Maps Map1 Albury-Wodong showing location in south east Australia Map2 Albury-Wodonga Aerial Photographs Aerial photograph of Albury and Wodonga 1971 Aerial photograph of Albury2007 iii Aerial photograph of Wodonga 2007 Abbreviations and Acronyms Appendix 1 State government and AWDC incentives for industry New South Wales incentives. -

Biographies of the Parliamentary Delegation From

*** * 14 I 3 * COUNCIL ** ** CONSEIL OF EUROPE * * DE L'EUROPE Parliamentary Assembly Assemblée parlementaire PACECOM087321 30 September 1994 AAINF5.94 AS/Inf(1994)5 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATIONS FROM: AUSTRALIA, CANADA AND JAPAN TO THE FOURTH PART OF THE 1994 ORDINARY SESSION OF THE PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE (3 - 7 OCTOBER 1994) AUSTRALIAN PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATION TO THE EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS & FRANCE SEPTEMBER / OCTOBER 1994 Hon Roger Price MP, Delegation Leader Member for Chifley (New South Wales) Australian Labor Party Hon Lou Lieberman MP, Deputy Delegation Leader Member for Indi (Victoria) Liberal Party Hon Wendy Fatin MP Member for Brand (Western Australia) Australian Labor Party Mr Eric Fitz gibbon MP Member for Hunter (New South Wales) Australian Labor Party Senator Nick Minchin Senator for South Australia Liberal Party PRICE, the Hon. Leo Roger Spurway Conferences, Delegations and Visits Member for Chifley (NSW) Australian Labor Party Member, Parliamentary Delegation to India and Sri Lanka, November 1986. Leader, Parliamentary Delegation to 18th General Parliamentary Service Assembly of AIPO, Jakarta, Indonesia, and bilateral visits to Thailand and Papua Now Elected to the House of Representatives for Guinea, September-October 1992; Papuaé Chifley, New South Wales, 1984,1987,1990 New-Guinea, November 1992. and 1993. Personal Parliamentary Appointments Born 26.11.45 at Sydney, NSW. Member, Advisory Council for Married Intergovenunent Relations from 13.3.85 to 1986. Qualifications and Occupation before entering Federal Parliament Ministerial Appointments DipTech (PubAdmin) (NSWIT). Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Account Manager, Telecom Australia. Minister from 4.6.91 to 27.12.91. Deputy Chairman, mt Druitt Hospital 1980- Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for 85. -

25 March 1986, Which Is Next Tuesday

Absence ofMinister 20 March 1986 ASSEMBLY 449 Thursday, 20 March 1986 The SPEAKER (the Hon. C. T. Edmunds) took the chair at 10.35 a.m. and read the prayer. ABSENCE OF MINISTER The SPEAKER-Order! I advise the House that the Minister for Transport is interstate and will be absent from this sitting of the House. QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE STATE FRINGE BENEFIT TAX LIABILITY Mr DELZOPPO (Narracan)-In the absence of the Minister for Property and Services, I direct my question to the Treasurer. Will the Treasurer inform the House what will be the Victonan Government's 1986-87 Commonwealth fringe benefit tax liability in respect of State public sector employee housing, if tenants of these residences are not charged market rents? Mr JOLLY (Treasurer)-The calculation of the liability depends on the number of employees in the public sector who are in that position at the time the legislation is passed in Federal Parliament. The Government will make the appropriate calculations once the legislation is passed and will examine how many people are in that position. FRINGE BENEFIT TAX ON MOTOR VEHICLES Mr ROSS-EDWARDS (Leader of the National Party)-I refer the Treasurer to the recent discussions and negotiations that have taken place between the Federal Treasurer and the Premier of South Australia regarding the fringe benefit tax on motor vehicles that are used partly for private and business purposes and the effect that the fringe benefit tax will have on the motor industry in South Australia. Has the Treasurer had discussions with either the Federal Treasurer or other members of the Federal Government about the effect that the fringe benefit tax on motor vehicles will have on the Victorian motor industry? If the Treasurer has had discussions, could he advise the House of the outcome of those negotiations? Mr JOLLY (Treasurer)-As honourable members would be aware, when the new tax package was announced by the Federal Government, both the Premier and I expressed concern at the effects that it would have on the motor vehicle industry. -

16 April 1986 ASSEMBLY 1173

VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) FIFTIETH PARLIAMENT AUTUMN SESSION 1986 Legislative Assembly VOL. CCCLXXXII [Prom April 10, 1986, to May 8, 1986J MELBOURNE: F. D. ATKINSON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 The Governor His Excellency the Reverend DR JOHN DA VIS MCCAUGHEY The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable SIR JOHN McINTOSH YOUNG, KCMG The Ministry (From 8 April 1986) Premier The Hon. John Cain, MP Deputy Premier, and Minister for Industry, Technology and Resources The Hon. R. C. Fordham, MP Minister for Agriculture and Rural Affairs The Hon. E. H. Walker, MLC Minister for Health The Hon. D. R. White, MLC Minister for Education The Hon. I. R. Cathie, MP Minister for Labour The Hon. S. M. Crabb, MP Minister for Community Services The Hon. C. J. Hogg, MLC Treasurer The Hon. R. A. Jolly, MP Attorney-General, and Minister for Planning and Environment .. The Hon. J. H. Kennan, MLC Minister for Conservation, Forests and Lands The Hon. J. E. Kirner, MLC Minister for the Arts, and Minister for Police and Emergency Services The Hon. C. R. T. Mathews, MP Minister for Water Resources, and Minister for Property and Services The Hon. Andrew McCutcheon, MP Minister for Transport The Hon. T. W. Roper, MP Minister for Local Government .. The Hon. J. L. Simmonds, MP Minister for Consumer Affairs, and Minister for Ethnic Affairs The Hon. P. C. Spyker, MP Minister for Sport and Recreation The Hon. -

Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard No. 6, 2002 THURSDAY, 27 JUNE 2002 FORTIETH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard SITTING DAYS—2002 Month Date February 12, 13, 14 March 11, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21 May 14, 15, 16 June 17, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26, 27 August 19, 20, 21, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29 September 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26 October 14, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24 November 11, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20, 21 December 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM SENATE CONTENTS THURSDAY, 27 JUNE Privilege.............................................................................................................. 2779 Personal Explanations......................................................................................... 2779 Petitions— Science: Stem Cell Research ......................................................................... 2781 Notices— Presentation .................................................................................................. -

Abbott's Gambit

Abbott’s Gambit The 2013 Australian Federal Election Abbott’s Gambit The 2013 Australian Federal Election Edited by Carol Johnson and John Wanna (with Hsu-Ann Lee) Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Abbott’s gambit : the 2013 Australian federal election / Editors, Carol Johnson and John Wanna (with Hsu-Ann Lee). ISBN: 9781925022100 (paperback) 9781925022094 (ebook) Subjects: Australia--Parliament--Elections--2013. Elections--Australia--2013. Political campaigns--Australia--21st century. Australia--Politics and government--21st century. Other Creators/Contributors: Johnson, Carol, 1955- editor. Wanna, John, editor. Lee, Hsu-Ann, editor. Dewey Number: 324.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface and Acknowledgements . ix Contributors . xiii Introduction: Analysing the 2013 Australian Federal Election . 1 Carol Johnson, John Wanna and Hsu-Ann Lee Part 1. Campaign Themes and Context 1 . An Overview of the 2013 Federal Election Campaign: Ruinous politics, cynical adversarialism and contending agendas . 17 Jennifer Rayner and John Wanna 2 . The Battle for Hearts and Minds . 35 Carol Johnson 3 . The Leadership Contest: An end to the ‘messiah complex’? . 49 Paul Strangio and James Walter Part 2. Vital Images of the Campaign—The Media, Campaign Advertising, Polls, Predictions and the Cartoons 4 .