Children's Perspectives on Education, Mobility, Social Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Running Head: COMMUNITY RESPONSE to OVC

Community Response to OVC…1 Running Head: COMMUNITY RESPONSE TO OVC Community Response to Provision of Care and Support for Orphans and Vulnerable Children, Constraints, Challenges and Opportunities: The Case of Chagni Town, Guangua Woreda Yohannes Mekuriaw Addis Ababa University A Thesis Submitted to the Research and Graduate Programs of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work (MSW) Advisor: Professor Alice Johnson Butterfield June 2006 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Community Response to OVC…2 Addis Ababa University Research and Graduate Program Community Response to Provision of Care and Support for Orphans and Vulnerable Children, Constraints, Challenges and Opportunities: The Case of Chagni Town, Guangua Woreda Yohannes Mekuriaw Graduate School Of Social Work Approved By Examining Board Advisor____________________ Signature _______Date_______________________ Examiner________________ Signature _________ Date_______________ Community Response to OVC…3 DEDICATION This Thesis is dedicated to my deceased Mother w/ro Simegnesh Shitahun without which my Educational Career Development would have been impossible. Community Response to OVC…4 Acknowledgement My first gratitude and appreciation goes to my thesis advisor, Prof. Alice K. Johnson Butterfield who critically commented on my thesis proposal and the report of the findings. Prof. Nathan Linsk also deserves this acknowledgment for his invitation to join a small group discussion with graduate students of social work who were working their Thesis on HIV/AIDS, and for his constructive comments on data collection tools and methods before fieldwork. I also thank Addis Ababa University for the small grant it provided to conduct the research. My wife Dejiytinu, with my child Kiduse, and my sister Rahael also shares this acknowledgement for I have been gone from my family role sets as a husband, father and a brother because of the engagement with my education these past two years. -

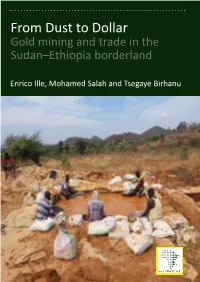

From Dust to Dollar Gold Mining and Trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia Borderland

From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland [Copy and paste completed cover here} Enrico Ille, Mohamed[Copy[Copy and and paste paste Salah completed completed andcover cover here} here} Tsegaye Birhanu image here, drop from 20p5 max height of box 42p0 From Dust to Dollar Gold mining and trade in the Sudan–Ethiopia borderland Enrico Ille, Mohamed Salah and Tsegaye Birhanu Cover image: Gold washers close to Qeissan, Sudan, 25 November 2019 © Mohamed Salah This report is a product of the X-Border Local Research Network, a component of the FCDO’s Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) programme, funded by UK aid from the UK government. XCEPT brings together leading experts to examine conflict-affected borderlands, how conflicts connect across borders, and the factors that shape violent and peaceful behaviour. The X-Border Local Research Network carries out research to better understand the causes and impacts of conflict in border areas and their international dimensions. It supports more effective policymaking and development programming and builds the skills of local partners. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. The Rift Valley Institute works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2021. This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE REPORT 2 Contents Executive summary 5 1. Introduction 7 Methodology 9 2. The Blue Nile–Benishangul-Gumuz borderland 12 The two borderland states 12 The international border 14 3. -

Commercialization of Teff Production in West North Ethiopia

Commercialization of Teff production in West North Ethiopia Habtamu Mossie ( [email protected] ) Injibara University of Ethiopia Dubale Abate Wolkite University Eden Kasse Injibara Minster of Finance and revenue Research Article Keywords: Double hurdle model, Market participation, Market orientation, Teff, Ethiopia Posted Date: August 16th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-812219/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Commercialization of Teff production in West North Ethiopia Habtamu Mossie1* Dubale Abate 2 Eden Kasse3 1*Department of Agricultural Economics, Inijbara University College of Agriculture, food and Climate Injibara, Ethiopia 2Department of Agribusiness and value chain management, Wolkite University, Wolkite, Ethiopia 3Eden Kasse Department of Agricultural Economics, Injibara Minster of Finance and revenue Corresponding author E-mail: habtamu. [email protected] ABSTRACT Background: Teff is only cereal crop Ethiopia’s in terms of production, acreage, and the number of farm holdings. It is one of the staples crops produced in the study area. However, the farm productivity, commercialization and level of intensity per hectare is low compared to the other cereals , Despite, smallholder farmers are not enough to participate in the teff market so the commercialization level is very low due to different factors. so, the study aimed to analyze determinants of smallholder farmer’s teff commercialization in west north, Ethiopia. Methods; A three-stage sampling procedure was used to take the sample respondents, 190 smallholder teff producers were selected to collect primary data through semi-structures questionnaires. Combinations of data analysis methods such as descriptive statistics and econometrics model (double hurdle) were used. -

Phenotypic Characterization of Indigenous Chicken Ecotypes in Awi Zone, Ethiopia

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology 2020; 5(4): 131-139 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/eeb doi: 10.11648/j.eeb.20200504.13 ISSN: 2575-3789 (Print); ISSN: 2575-3762 (Online) Phenotypic Characterization of Indigenous Chicken Ecotypes in Awi Zone, Ethiopia Andualem Yihun 1, Manzoor Ahmed Kirmani 2, Meseret Molla 3 1Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Oda Bultum University, Chiro, Ethiopia 2Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia 3Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Natural Resource, University of Gonder, Gonder, Ethiopia Email address: To cite this article: Andualem Yihun, Manzoor Ahmed Kirmani, Meseret Molla. Phenotypic Characterization of Indigenous Chicken Ecotypes in Awi Zone, Ethiopia. Ecology and Evolutionary Biology . Vol. 5, No. 4, 2020, pp. 131-139. doi: 10.11648/j.eeb.20200504.13 Received : October 2, 2020; Accepted : October 21, 2020; Published : November 4, 2020 Abstract: The study was conducted in three districts of Awi zone in Amhara region, with the aim to characterize and identify the phenotypic variation of indigenous chicken ecotypes. A total of 720 indigenous chicken ecotypes were (504) females and (216) males from the whole districts) to describe qualitative and quantitative traits. Local chicken were mostly normally feathered and large phenotypic variability among ecotypes was observed for plumage color. A many plumage colors were identified in all districts in which Red in high-land and mid-land and Gebsima (grayish) colours in low-land were the predominant color of the study area beside a large diversity. The average body weight of local chickens in high-land, mid-land and low-land agro-ecologies were 1.476, 1.75 and 1.71kg respectively, while the respective values for mature cocks and hens were 1.78 and 1.51kg. -

English-Full (0.5

Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Building Climate Resilient Green Economy in Ethiopia Strategy for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations Wubalem Tadesse Alemu Gezahegne Teshome Tesema Bitew Shibabaw Berihun Tefera Habtemariam Kassa Center for International Forestry Research Ethiopia Office Addis Ababa October 2015 Copyright © Center for International Forestry Research, 2015 Cover photo by authors FOREWORD This regional strategy document for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State, with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations, was produced as one of the outputs of a project entitled “Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy”, and implemented between September 2013 and August 2015. CIFOR and our ministry actively collaborated in the planning and implementation of the project, which involved over 25 senior experts drawn from Federal ministries, regional bureaus, Federal and regional research institutes, and from Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources and other universities. The senior experts were organised into five teams, which set out to identify effective forest management practices, and enabling conditions for scaling them up, with the aim of significantly enhancing the role of forests in building a climate resilient green economy in Ethiopia. The five forest management practices studied were: the establishment and management of area exclosures; the management of plantation forests; Participatory Forest Management (PFM); agroforestry (AF); and the management of dry forests and woodlands. Each team focused on only one of the five forest management practices, and concentrated its study in one regional state. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

ETHIOPIA: Benishangul Gumuz Region Flash Update 6 January 2021

ETHIOPIA: Benishangul Gumuz Region Flash Update 6 January 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • Between end of July 2020 and 04 January 2021, more than 101,000 people were displaced by violence from A M H A R A Bullen, Dangur, Dibate, Guba, Mandura and Wombera Guba woredas of Metekel zone in Dangura Benishangul Gumuz Region 647 Pawe (BGR). 5,728 • Due to the deteriorating security situation in the zone, 12,808 Sedal Madira humanitarian access and life- Metekel saving assistance to the 28,000 returnees and 101,000 SUDAN B E N I SHA N G U L Sherkole G U M U Z new IDPs is challenging. Kurmuk • The regional Government has Wenbera Debati 23,121 been providing limited life- Menge 7,885 51,003 saving assistance since July Homosha Bulen 2020 using armed escorts. Undulu • Clusters at sub-national level Asosa Bilidigilu have been mapping resources Assosa Zayi but so far insecurity has not Kemeshi allowed transporting staff and Dembi O R O M I A commodities to affected Bambasi O R O M I A areas. Maokomo Kamashi • Special The federal Government is in C Mizyiga the process of establishing an Affected zone Emergency Coordination N A ## No. of IDPs per woreda Nekemte Center (ECC) in Metekel zone D UBLI to coordinate the P IDPs movement humanitarian response to the SU RE Humanitarian Western Hub IDPs. SOUTH OF SITUATION OVERVIEW Security in Metekel Zone of Benishangul Gumuz Region (BGR) has been gradually deteriorating since 2019, and more intensely so in recent months. On 23 December 2020, 207 individuals lost their lives in one day reportedly following an attack by unidentified armed groups (UAGs). -

AMHARA Demography and Health

1 AMHARA Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 2021 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org 2 Amhara Suggested citation: Amhara: Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 20201 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org Landforms, Climate and Economy Located in northwestern Ethiopia the Amhara Region between 9°20' and 14°20' North latitude and 36° 20' and 40° 20' East longitude the Amhara Region has an estimated land area of about 170000 square kilometers . The region borders Tigray in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumiz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan to the west [1]. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 140 Weredas (see map at the bottom of this page). There are about 3429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) [1]. "Decision-making power has recently been decentralized to Weredas and thus the Weredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas." The 11 administrative zones are: North Gonder, South Gonder, West Gojjam, East Gojjam, Awie, Wag Hemra, North Wollo, South Wollo, Oromia, North Shewa and Bahir Dar City special zone. [1] The historic Amhara Region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, and millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. In this Region are located, the world- renowned Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder, and Lalibela. "Interspersed on the landscape are higher mountain ranges and cratered cones, the highest of which, at 4,620 meters, is Ras Dashen Terara northeast of Gonder. -

Husbandry Practice and Reproductive Performance of Indigenous Chicken Ecotype in Awi Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia

International Journal of Applied Agricultural Sciences 2020; 6(6): 179-184 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijaas doi: 10.11648/j.ijaas.20200606.13 ISSN: 2469-7877 (Print); ISSN: 2469-7885 (Online) Husbandry Practice and Reproductive Performance of Indigenous Chicken Ecotype in Awi Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Andualem Yihun Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Injibara University, Injibara, Ethiopia Email address: To cite this article: Andualem Yihun. Husbandry Practice and Reproductive Performance of Indigenous Chicken Ecotype in Awi Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. International Journal of Applied Agricultural Sciences . Vol. 6, No. 6, 2020, pp. 179-184. doi: 10.11648/j.ijaas.20200606.13 Received : October 2, 2020; Accepted : October 21, 2020; Published : December 4, 2020 Abstract: The study was conducted to generate comprehensive information on Husbandry practice and Reproductive performance of indigenous chicken ecotype in Awi zone in Adiss-kidame town in fagita district of Awi Zone, Amahara Regional State, Ethiopia. The study was performed based on household survey and observation. For household survey, three kebeles were selected and a total of 60 households (20 from each kebeles) were involved. Most of the household in the study area was practiced backyard chicken production systems (73.3%). The major objective of raising chicken in the study area was egg production (46.7%) and income generation (46.7%). The majority of the households in the study area were practiced semi- extensive management systems (60%). The entire households in the study area were providing supplementary feed and water for their chicken. The age of cockerels at first mating and pullets at first egg laying were 5.21 months and 5.77 months, respectively. -

07 33880Rsj100818 53

Researcher 2018;10(8) http://www.sciencepub.net/researcher Prevalence of Bovine Trypanosomosis in selected kebeles of Guangua, woreda, Amhara region, north west part of Ethiopia. Abere Dawud and *Asmamaw Aki Regional Veterinary Diagnostic, Surveillance, Monitoring and Study Laboratory, P.O.Box:326, Asossa, Ethiopia; email address: [email protected]; Cele phone: +251902330029 Abstract: Trypanosomosis is wasting disease of tropical countries that contribute negatively to benefit human and productivity of animal. The Cross sectional study was conducted in selected Kebeles of Guangua Woreda, Amhara Region, North West Part of Ethiopia from November 2017 to April 2018 to determine the prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis on randomly selected animal using parasitological study (Buffy coat technique). Total of 384 blood samples were collected from four kebele and examined. The result of parasitological finding indicates 1.82% of total prevalence in the study area. In the present study two species of Trypanosoma identified, from total (7) positive sample 4(1.04%) was showed Trypanosoma vivax and 3(0.78%) of them indicate Trypanosoma congolense. The present study indicate there were no statistically significant difference (p>0.05) observed between kebele, sex and age group of animal whereas statistically significant difference (p<0.05) was observed in body condition. In this study the anemia prevalence was higher in trypanosome infected cattle (71.4%) than in non-infected cattle (28.6%) and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.05). The present study showed that there was slightly higher prevalence than previous study which was conducted in Woreda. In general the prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in the study area was minimum, this may be due to seasonality of fly population Therefore, further study should be conduct in this area especially in wet season to understand the prevalence of the disease and its effect on bovine. -

Melanie Ramasawmy Thesis

DOCTORAL THESIS Do ‘chickens dream only of grain’? Uncovering the social role of poultry in Ethiopia Ramasawmy, Melanie Award date: 2017 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 Do ‘chickens dream only of grain’? Uncovering the social role of poultry in Ethiopia. By Melanie R Ramasawmy BA, BSc, MSc A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Life Sciences University of Roehampton 2017 i Abstract The Amharic proverb ‘Chickens dream only of grain’ could easily describe our own lack of imagination when thinking about poultry. In the sectors of agriculture and development, there is growing recognition of how chickens could be used in poverty alleviation, as a source of income and protein, and a means of gender empowerment. However, interventions do not always achieve their goals, due to a lack of understanding of the local context in which chickens will be consumed.