What Alternative Punishment Is There?”: Military Ex- Ecutions During World War I Thesis How to Cite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

55Th Foot Reeneactors

The Newsletter supports Cumbria’s Museum of TheLion& Military Life. theDragon TheFriendsofCumbria’sMuseumofMilitaryLife Winter2019 Contents 55th Foot. Still loyal in Illinois Regimental vehicles - Saracen Woodhall Spa Memorial window Full Museum Accreditation Cumbria Militia archive appeal w Bookshelf Duke of Lancaster's News Museum & Friends News Diary Lest we forget Welcome Museums are not just e storehouses of objects. They offer chances to study and they encourage an interest in history. Both objectives that are shared with living history groups. 'The Lion and the Dragon' is grateful to the 'Recreated 55th Regiment of Foot', from Illinois, for q r providing a glimpse of one of the antecedent regiments to the Duke of 55thFoot.StillloyalinIllinois. Lancaster's Regiment. Thanks to the '55th The scene is a living history event, a British army He looks around. About thirty feet away a guard has Foot' we can revisit the encampment circa 1776. The history being portrayed just been posted at an intersection of a dirt road. He American War of happened two hundred forty-three years ago on the east stands with a fixed bayonet and musket at the support. Independence and learn a coast of His Majesty’s rebellious colonies in America, but About ten feet to the teenager’s left a row of sun- little of everyday life in this particular day the site is in the countryside bleached tents are pitched. In front of one there appears the colonies 250 years surrounding Chicago, Illinois. to be a very experienced soldier taking a break. He uses ago. a full knapsack as a pillow and his cocked hat is shifted A modern teenager has just entered a simulation not Peter Green to block the sun from his eyes. -

Copeland District War Memorials Transcript

COPELAND War Memorials Names Lists THWAITES MEMORIAL-TRANSCRIPTION TO THE GLORIOUS MEMORY OF THE MEN OF THIS/PARISH WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918/ THOMAS ALBERT BUTTERFIELD KING’S OWN ROYAL LANCASTER/ EDWARD GARNETT GRENADIER GUARDS/ THOMAS FISHER 2ND CANADIAN CONTINGENT/ WILLIAM HARRISON KING’S OWN ROYAL LANCASTER/ CHARLES GILFRID LEWTHWAITE MC ROYAL FIELD ARTILLERY/ WILLIAM LOWERY KING’S OWN ROYAL LANCASTER/ WILLIAM NORMAN KING’S OWN ROYAL LANCASTER/ WILLIAM GREY RAWLINSON DUKE OF CORNWALL’S LIGHT INFANTRY/ CASSON STEPHENSON ROYAL FIELD ARTILLERY/ HENRY WILFORD CANADIAN CONTINGENT/ ALSO IN THE WAR 1939-1945/ ARTHUR HIBBERT ROYAL ARTILLERY/ GILFRID MACIVER LEWTHWAITE ROYAL AIR FORCE VR/ JOSEPH STEELE ROYAL NAVY/ MATSON TROUGHTON ROYAL CORPS OF SIGNALS/ LEST WE FORGET THWAITES CG LEWTHWAITE BATTLEFIELD CROSS-TRANSCRIPTION IN MEMORY OF/LIEUT CG LEWTHWAITE MC/C231 BRIGADE RFA/KILLED IN ACTION/JULY/29TH 1917 Page 1 of 218 Haverigg War Memorial-TRANSCRIPTION FRONT (WW1) TO THE/GLORY OF GOD/AND/IN GRATEFUL MEMORY/OF THE/MEN OF HAVERIGG/WHO/GAVE THEIR LIVES/IN/THE GREAT WAR/1914-1918 Edward Atkinson/William J. Baker/John T. Brocklebank/George Brown/Edward N. Burn/William Cartwright/James Cartwright/ James Cleasby/Henry P. Dobson/James Doloughan/Richard T. Duke/Richard Floyd/Walter Hammond/Edward J. Hoskin/ Anthony High/John Jackson/Thomas Jackson/William E. Johnson/Christopher Kewley/George Langhorn/John Lorraine/ James Longridge/Edward Metters/William H. Milton/Thomas Mitchell/Joseph Poland/William H. Rowland/Ernest Sage/ Walter Stables/Fred Temp/George Thomas/John Thomas/John G. Tomlinson/William Watson/Frederick H. Worth RIGHT HAND SIDE (WW2) E.J. -

Notes from the Chairman

Spring 2011 Issue 12 Registered Charity No 271943 THE LION AND THE DRAGON NEWSLETTER of THE Friends of Cumbria’s Military Museum The Border Regiment, King’s Own Royal Border Regiment & Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment CONTENTS Notes From The Chairman ...................................... Page 1 The Alma Project ........ Page 2 The Biggest Meccano Kit In The World ............................ Page 2 Notes from the Chairman The Heritage & Archaeology of Alma Block ................... Page 3 Museum Jottings ......... Page 3 Despite the fact we have experienced one of the most severe winters Metal Detecting Rally, Underley for many a year with snow, ,ice, freezing temperatures, airports Park, September 2010 Page 4 closed, rail and road networks paralysed, the flu virus rampant, all Bonfire Night on The this and much more did not dampen the enthusiasm, dedication and commitment for the move of the Museum currently located in Queen Battlements .................. Page 4 Mary‟s Tower to Alma block in the Outer Ward of Carlisle Castle. Catching Culture & Inspiring Imaginations ................ Page 4 There will be a number of events organised by the Friends and the New Booklet ................. Page 5 Museum Support Group in 2011 to support fund-raising for this Who Do You Think You Are? essential move. The Museum Appeal still has to raise considerable ……………………….. .... Page 5 match funding and I appeal to all our readers to spread the news What’s In A Name?.. .... Page 6 throughout the county and beyond; any donation large or small will The 55th (Westmorland) be gratefully received and faithfully applied. The Museum is also trying to build up a pool of volunteers for a variety of tasks. -

A Technical, Administrative and Bureaucratic Analysis of the Victoria Cross and the AIF on the Western Front, 1916-1918

i Behind the Valour: A technical, administrative and bureaucratic analysis of the Victoria Cross and the AIF on the Western Front, 1916-1918 Victoria D’Alton Student Number 3183439 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 22 October 2010 ii Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Victoria D’Alton UNSW Student Number 3183439 22 October 2010 iii For my friend, Lieutenant Paul Kimlin, RAN O156024 1 January 1976 – 2 April 2005 ‘For many are called, but few are chosen.’ Matthew 22:14 iv Abstract This thesis focuses on the how and why the Victoria Cross came to be awarded to 53 soldiers of the AIF on the Western Front from 1916 to 1918. It examines the technical, administrative and bureaucratic history of Australia’s relationship with the Victoria Cross in this significant time and place. -

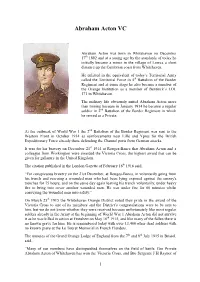

Abraham Acton VC

Abraham Acton VC Abraham Acton was born in Whitehaven on December 17th 1892 and at a young age by the standards of today he initially became a miner in the village of Lowca a short distance up the Cumbrian coast from Whitehaven. He enlisted in the equivalent of today’s Territorial Army called the Territorial Force in 5th Battalion of the Border Regiment and at some stage he also became a member of the Orange Institution as a member of Bentinck’s LOL 171 in Whitehaven. The military life obviously suited Abraham Acton more than mining because in January 1914 he became a regular nd soldier in 2 Battalion of the Border Regiment in which he served as a Private. At the outbreak of World War 1 the 2nd Battalion of the Border Regiment was sent to the Western Front in October 1914 as reinforcements near Lille and Ypres for the British Expeditionary Force already there defending the Channel ports from German attacks. It was for his bravery on December 21st 1914 at Rouges-Bancs that Abraham Acton and a colleague from Workington were awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award that can be given for gallantry in the United Kingdom. The citation published in the London Gazette of February 16th 1916 said, “For conspicuous bravery on the 21st December, at Rouges-Bancs, in voluntarily going from his trench and rescuing a wounded man who had been lying exposed against the enemy's trenches for 75 hours; and on the same day again leaving his trench voluntarily, under heavy fire to bring into cover another wounded man. -

55Th Foot. Still Loyal in Illinois. Lancaster's Regiment

The Newsletter supports Cumbria’s Museum of The Lion & Military Life. Thethe Friends of Cumbria’s DragonMuseum of Military Life Winter 2019 Contents 55th Foot. Still loyal in Illinois Regimental vehicles - Saracen Woodhall Spa Memorial window Full Museum Accreditation Cumbria Militia archive appeal w Bookshelf Duke of Lancaster's News Museum & Friends News Diary Lest we forget Welcome Museums are not just e storehouses of objects. They offer chances to study and they encourage an interest in history. Both objectives that are shared with living history groups. 'The Lion and the Dragon' is grateful to the 'Recreated 55th Regiment of Foot', from Illinois, q r for providing a glimpse of one of the antecedent regiments to the Duke of 55th Foot. Still loyal in Illinois. Lancaster's Regiment. Thanks to the '55th The scene is a living history event, a British army just been posted at an intersection of a dirt road. He Foot' we can revisit encampment circa 1776. The history being portrayed stands with a fixed bayonet and musket at the support. the American War of happened two hundred forty-three years ago on the east About ten feet to the teenager’s left a row of sun- Independence and learn coast of His Majesty’s rebellious colonies in America, bleached tents are pitched. In front of one there appears a little of everyday life in but this particular day the site is in the countryside to be a very experienced soldier taking a break. He uses the colonies 250 years surrounding Chicago, Illinois. a full knapsack as a pillow and his cocked hat is shifted ago. -

Carlisle District War Memorials

CARLISLE War Memorials Names Lists UPPERBY CEMETERY (Civil Parish of St. Cuthbert without) WW1, Transcription Base 1: 950 sq x 270 high, Base 2-750mm sq x 230 high, Base 3-610 sq x 230 high, Obelisk 430 s q x 2300 high IN/LOVING REMEMBRANCE/OF THE MEN OF THE PARISH/OF ST. CUTHBERT WITHOUT/WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR/1914-1918/ 6 o’clock face J. ADAMTHWAITE BLACKWELL/GEORGE ALLEN CARLETON/ROBERT BELL CURTHWAITE/ FRANCIS C CARLYLE CARLETON/JOHN DUCKWORTH BLACKWELL/ JAMES GILL SCUGGAR HOUSE/TAYLOR GRAHAM CROWNSTONE/JOSEPH GIBBONS WOODBANK/ EWART GLAISTER CARLETON/JOHN G CHISHOLM BLACKWELL 3 o’clock face ALBERT GAUGHY UPPERBY/T HENDERSON CURTHWAITE/T J HARRISON BLACKWELL/ R HOLLIDAY BLACKWELL/ROBERT KEDDIE UPPERBY/JOHN W LITTLE UPPERBY/ THOMAS LITTLE UPPERBY/THOMAS MOFFITT BRISCO/SAMUEL MATTHEWS WOODBANK/ J W NICHOLSON BRISCO/STEPHEN PUTLAND UPPERBY/EDWARD ROBERTSON UPPERBY/ JOHN H SMITH WOODBANK/WARWICK J STEEL LOW MOOR COTTAGE Page 1 of 202 RICHARDSON STREET CEMETERY WW1 (NE CORNER OF WARD 11, THE WW2 cross is the NE corner of Ward 16). Each panel is 1160mm high x 405mm wide x 10mm thick. 6 o’clock CITY OF CARLISLE/OFFICERS AND MEN/OF THE/NAVY AND ARMY/WHO ARE BURIED IN THE/CARLISLE CEMETERIES LIEUT COL WF NASH BORDER REGT/ MAJOR FW AUSTIN BORDER REGT/ CAPT WILLIAM FINCH RE/ CAPT HPD HELM RAF 7 BR REGT/ LIEUT CHARLES TUFFREY RDC/ 2 LIEUT RC HINDSON RFA/ 2LIEUT TB RUTH BORDER REGT/ 2LIEUT CS RUTHERFORD 2ND BORDER REGT/ 2LIEUT RH LITTLE RAF/ CONDTR CH BUCK SSA2 BAC/ MAJOR R EDWARDS RAMC/ CAPT GEORGE CURREY RAVC/ B1766 AB THOMAS MORTON/ANSON