Statement for the Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Foo a Japanese-American Prisoner of The

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Foo A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun—The Secret Prison Diary of Frank Foo Fujita by Fr Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun—The Secret Prison Diary of Frank "Foo" Fujita by Frank Fujita. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #c33f0660-ce5d-11eb-b18f-1d55c07f11d6 VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Wed, 16 Jun 2021 04:46:06 GMT. GetBestBooks. [PDF] [EPUB] Shadow Touched: Be Careful What You Wish For… Download. [PDF] [EPUB] Shadow Touched: Be Careful What You Wish For… Download by Gabriel Colton . Download Shadow Touched: Be Careful What You Wish For… by Gabriel Colton in PDF EPUB format complete free. [Read more…] about [PDF] [EPUB] Shadow Touched: Be Careful What You Wish For… Download. [PDF] [EPUB] Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun—The Secret Prison Diary of Frank Foo Fujita Download. [PDF] [EPUB] Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun—The Secret Prison Diary of Frank Foo Fujita Download by Frank Fujita . Download Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun—The Secret Prison Diary of Frank Foo Fujita by Frank Fujita in PDF EPUB format complete free. [Read more…] about [PDF] [EPUB] Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun—The Secret Prison Diary of Frank Foo Fujita Download. -

The Lost Battalion: Second Battalion 131St Field

A'siO THE LOST BATTALION: SECOND BATTALION 131ST FIELD ARTILLERY, 1940-1945 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Elmer Ray Milner, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 Milner, Elmer Ray, The Lost Battalion: Second Battalion, 131st Field Artillery, 1940-1945. Master of Arts (History), August, 1975, 106 pp., bibliography, 53 titles. As a part of the Texas National Guard, the Second Battalion of the 131st Field Artillery went on active duty as World War Two errupted and eventually became trapped in Java by Japanese forces. It became known as the Lost Battalion after its surrender because it lost all communication with the Allies for over three years. The Japanese forced these Americans to work in Burma on a railroad construction project connecting Burma to Thailand. After the railroad's completion in 1944, the Lost Battalion remained in various prisoner-of-war camps until liberation came in August, 1945. Research sources consulted include the prisoner-of-war project of the North Texas State University Oral History Collection, published memoirs of former captives, pertinent United States government documents, and contemporary newspapers. Secondary materials investigated embrace books and periodicals. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .. 0. iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION. 1 II. FEDERALIZATION OF THE TEXAS THIRTY-SIXTH DIVISION . 4 III. ASSIGNMENT OF THE SECOND BATTALION TO THE SOUTH PACIFIC. 15 IV. UNITED STATES-NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES RELATIONS. 34 V. SURRENDER AND EARLY CONFINEMENT . 67 VI. LATER CONFINEMENT . 77 VII. LIBERATION. 94 VIII. -

The Pacific Citizen Is Moving Back to Little Tokyo! Effective Oec

The Pacific Citizen is moving back to Little Tokyo! Effective Oec. 1 250 E. First Street~ Suite 301 Check out the P.C:s our address will be: Los Angeles~ CA 90012 new Web site! (800) 966·6157 Since1929 ________________~------------_r~~~~--------- INSIDE Michelle Wie is disqualified in her ~CIFIC first appearance CITIZEN as a professional. The National Publication of the .Japanese American Citizens League PAGE 7 Are Foreign Exchange Students Safe? APA Political Newcomers Hope to • A Japanese girl's placement that placed the 'Turn the Tide' in Their Communities in the home of a convicted Japanese girl, say A handful of history-mak is extremely felon has raised demands they have not vio ing candidates across the important for criminal background lated any guide U.S. want to become elected because "there checks. Placement agencies lines and have officials in the November is not one <;ity counter the situation is since received per elections. or town in being overblown. mission from the America that girl's parents in By LYNDA LIN doesn't have Japan to continue Assistant Editor By CAROLINE AOYAGI-STOM CHRISTOPHER people of Asian Executive Editor her stay. And they ethnic back- This November, some Asian have the approval ground," she Should a convicted felon be Pacific Americans are hoping to of the U:S. State added. allowed to host a foreign exchange make history. Department to Christopher, student? A frrst generation APA born in the back them up. 35, is one of a That's the resounding question HAPPIER TIMES-Sally Smith's daughter United States like Supriya handful of APA after the Committee for the Safety "What prece- Jessica with Mary Vattanasiriporn (right) after Christopher not only wants to make dence does this Smith took the 16-year-old Thai girl into her home. -

Nichi Bei Weekly

2 JUNE 6 - 19, 2019 • NICHI BEI WEEKLY • Regional/National Symposium examines wartime scars Asian Americans push for By TOMO HIRAI carceration, the conflict and later its national director during Nichi Bei Weekly resistance inmates exhibited the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. representation at Smithsonian Institute More than three quarters of a during the war, and the post-war Tateishi spoke on the back- By KiMi ROBINSON “I can stand here tonight and century since the forced remov- activism that eventually won an ground behind the organiza- Kyodo News proclaim that I am an actor play- al and incarceration of some apology and token compensa- tion’s decision to comply with LOS ANGELES — More than ing roles casting for ‘male actor,’ 120,000 people of Japanese de- tion from the U.S. government the U.S. government’s plans 20 years after its founding as a but that wasn’t always the case,” scent in American concentra- in the 1980s. to forcibly remove people of diversity initiative, the Smithson- said the event’s emcee Harry tion camps, the Japanese Ameri- Chizu Omori, a Japanese Japanese descent from the West ian Asian Pacific American Cen- Shum Jr., an actor known for his can community still has not fully American writer and activist, Coast. ter is working to create a perma- roles in “Glee” and “Crazy Rich recovered from the trauma. served as the symposium direc- Tateishi, who joined the JACL nent Washington exhibit space Asians.” The day-long event entitled tor. Omori, who was 12 years old in 1975, said he spent years where visitors can learn about “There was a time when the “A Community Fractured: when she was incarcerated in questioning why the JACL en- the contributions Americans of script called for an Asian actor Compliance & Resistance” ex- Poston, Ariz., said she is some- dorsed the incarceration while Asia-Pacific descent have made that was portrayed by a non- plored the rifts within the Japa- times overcome with sadness working on the redress cam- to their country. -

The Death Railway at Chong Kai Tha1lane

if* < > i • x 4 i' > 4 f x L * » - .;'*f •>-“■- ■ *■ ■ K' - THE DEATH RAILWAY AT CHONG KAI THA1LANE LOST BATTALI01 ASSOCIATION ROSTER 2ND BATTALION 131ST HELD ARTILLERY & USS HOUSTON (CA-JO) SURVIVORS An amazing fact about our Roster is now after some 38 years it is just about completed. At the end of World War II when we were liberated and separated as groups we scattered to the four winds. Almost im mediately the effort was begun to locate the men of the 2nd Battalion 131st field Artillery and USS Houston (OA-30) survivors who by no circumstances of their own were first brought together in prison camps of the Japanese. The close bonds of friendship and brotherly love has continued over the.years and still continues to grow as time marches on. Our Roster has been an important factor in our “keeping together." Even as late as 1973 there were still some 288 members who had not been lo cated. Today, that number has been narrowed to nine men. Three of the nine have been located through the Navy finance Department in Cleveland, but regulations do not permit them to forward their addresses to us, there fore they continue in this catagory. One man is presumed dead, and no word on the others, A separate page has been prepared for these men. Please keep up the quest for these men. We need to know their status. Each person prefers to be identified with his own unit. The legend is as follows: H - Headquarters Battery D - "D" Battery E - "E" Battery F - "F" Battery S - Service Battery M - Medical Detachment N - Navy Personnel MO - Marine Corps Personnel AO - Army Officers NO - Navy Officers MOO - Marine Corps Officers The Roster is arranged alphabetically, and the first column shows the unit of assignment of each man. -

Java Advocate

Japanese American Veterans Association Summer 2017 JAVA ADVOCATE President’s Report Volume XXV, Issue II In March, JAVA helped to say farewell to former Maryland Secretary of Veterans Affairs Ed Inside This Issue: Chow at Arlington National Cemetery. He always honored the Farewell to Ed Chow 2 legacy of the 100th, 442nd, and MIS. We will miss him and his many OSU Honors John Hideo Houston 3 contributions to JAVA. Ishimoto & the Hawaii National Guard 4 In another transition, on May 31, President Mike Cardarelli handed Memorial Day: History and 2017 5 off JAVA leadership to new officers. Secretary Wade Ishimoto French Legion of Honor Assistance 6 LTC Allen Goshi, USA (Ret) and I joined Vice President Mark NVN Partners with Army Museum 7 Nakagawa and Treasurer George Ishikata to form the new team. Thanks to Mike Cardarelli andthe the war,” other spoke key of leaders the strength for theirand Meet the Generals and Admirals 8 professionalism and many contributionsdurability to of JAVA! the US -Japan alliance. Abe said, “What has bound us Modern-Day US Army Command 9 As I embark on this journey, I willtogether follow threeis keythe ideas. hope First, I amof committed to JAVA’s fundamentalreconciliation purposes. Ourmade predecessors’ possible Ambassador John Malott Honored 10 patriotism and loyalty, especiallythrough the Greatest the Generation spirit, who facedthe wartime discrimination, helped totolerance. secure justice What andI want equality. to appeal Their to 3rd Generation of Nakamotos in Army 11 legacy still resonates and guides theall peoplewho follow of the in world their herefootsteps. at Pearl th Harbor, together with President Legendary 100 Infantry Battalion 11 Second, we must maintain the momentum on important ongoing Obama, is this power of Maui Chapter Celebrates 75 Years 12 projects, like the NARA digitizationreconciliation. -

Burgmann Journal

Burgmann Journal R ESEA R CH D EBATE O PINI O N I SSUE II , 2 0 1 3 Burgmann Journal is a multidisciplinary, peer-reviewed publication of collected works of research, debate and opinion from residents and alumni of Burgmann College designed to engage and stimulate the wider community. Published by ANU eView The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://eview.anu.edu.au ISSN 2201-3881 (Print) ISSN 2201-3903 (Online) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Opinions published in the Burgmann Journal do not necessarily represent those of The Australian National University, Burgmann College, or the Editors. Front cover by Burgmann resident Hilary Hanrahan. According to Hilary, ‘This artwork was created through Photoshop using my own photograph of some new Bougainvillea buds growing on campus. The spray of flowers hanging over the fence looked good enough to eat’. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU eView Editorial Team: Patrick Carvalho Editor-in-Chief Matthew Calvin Editor Roderick Murchison Editor Ella Relf Editor Wen-Ti Sung Editor Associate Editors: Vincent Margerin Matthew Randall iii Academic Referees: Dr Shiro Armstrong Dr Michael Platow Research Fellow Professor International Development Economics Research School of Psychology -

Measuring Empowerment

MEASURING Public Disclosure Authorized EMPOWERMENT CROSS-DISCIPLINARY PERSPECTIVES Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized EDITED BY DEEPA NARAYAN THE WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized MEASURING EMPOWERMENT MEASURING EMPOWERMENT Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives Edited by Deepa Narayan THE WORLD BANK Washington, DC © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www.worldbank.org E-mail [email protected] All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 08 07 06 05 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

Terrorists on Sept

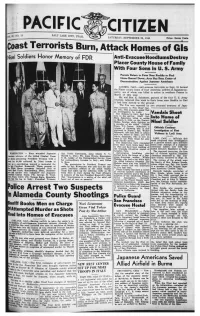

VOL. 21; NO. P12 ACSALTILAKEFCITY,IUTAH,C CITIZEN SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 1945 Price: Seven Cent* CoastTerrori stsBurn,AttackHomesofGIs Nisei Soldiers HonorMemory ofFDR Anti -Evacuee HoodlumsDestroy Placer County House of Family Wi th Four Sons i n U. S. Army Parents Return to Farm Near Rocklin to Find Home Burned Down; Area Has Been Center of Demonstrations Against Japanese Americans LOOMIS, Calif.—Anti-evacuee terrorists on Sept. 18 burned the Placer county h ome of four American soldiers of Japanesean- cestry, one of wh om was k i lled i n action i n southern France i n March ofthi s year. Mr. and Mrs. K. Sakamoto, parents of the four U. S. Army veterans, returned thi s week to their h ome near Rocklin to find i t h ad been burned to the ground. Th e fire was reported by two returned evacuees of Japa- nese ancestry to Fire Ch i ef Gar- ret Doty. Th e evacuees asked that an i nvestigation be made. Th e Sakamotos i h ave h ad four Vandals Sh oot sons i n the service: Staff Sgt. Masa Sakamoto, k i lled i n action Into Home of on March 3, 1945, on the Franco- Italian frontier wh i le figh ting as Nisei Soldier a j nember of the 442nd Combat Team; T/3 Cosma Sakamoto, a Officials veteran of Ok i nawa wh o i s now Continue stationed i n Hawaii ; Sgt. Walter Investigation of First Sakamoto, wih o h as been i n action Violence i n Lodi Area with the 442nd i n Italy; and T/3 Calvin Sakamoto, wh o i s now en route to the West Coast for pos- LODI, Calif. -

Eddie Fung Part 2 - Prisoner of War 1941-1942 by Philip Chin

Eddie Fung Part 2 - Prisoner of War 1941-1942 By Philip Chin In November 1941, 2nd Battalion of the 131st Field Artillery, 36th Infantry Division (Texas National Guard) shipped out from Texas. Nobody on board the train knew where their final destination would be, possibly Luzon or Manila in the Philippines they speculated. All they knew was that they were heading westwards. Eddie found out from a conductor in Flagstaff, Arizona that they were heading towards his hometown of San Francisco and would be going through Bakersfield, California where Jess, one of his older sisters lived. He called his sister and she met him with a suitcase full of baked cookies which she gave him during the fifteen minute stop. Eddie was happy to share the cookies with the men but wasn't told until then that he wasn't supposed to divulge troop movements. The train arrived in San Francisco and all the troops were then taken by ferry to Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. This was the site of the former immigration station which had just closed in 1940 where Asian immigrants had been held. Because of the anti- Asian immigration restrictions under federal law these immigrants and often American citizens by birth were held anywhere from days to months while their cases were being investigated and they were interrogated. Ironically the former immigration buildings would soon be used as prisoner of war barracks for German and Italian soldiers. Eddie got a pass on the second day and went home to see his mother. She asked him if he would be back to celebrate Thanksgiving and he said he didn't know because he didn't know how long his unit would be in town. -

THE WATSONVILLE-SANTA CRUZ JACL Newsletter July 2018

THE WATSONVILLE-SANTA CRUZ JACL Newsletter July 2018 CELEBRATING THE CIVIL LIBERTIES ACT We hope you and your family will be able to attend. OF AUGUST 10, 1988 There is no admission fee, and light refreshments will be served. As seating is limited, please RSVP Marcia Hashimoto at (831) 722-6859 or email at [email protected]. Sincerely, Marcia Hashimoto, President “WHAT IF . .” Editor “What If” not one Japanese American served in the United States military during World War II, and the war was won? Where would we of the Nikkei nation be today? We thank the 30,000 Nisei who did serve and honor and remember the 811 who were killed in action. “Liberty Lost …” logo created by Andy Fukutome; Our W-SC JACL members are grateful to all those who served with our 201 local heroes in the European and Pacific poster designed by Phil Shima. theaters during WW II: The Watsonville-Santa Cruz chapter of the National Women’s Army Corps Women’s Nurse Corps Japanese American Citizens League was privileged to have Florence Uyeda Toshiko Etow purchased Howard Ikemoto’s magnificent painting of the Iris A. Watanabe WWII incarceration camp guard tower. We cordially invite you and your family to join us for the presentation of Howard’s painting on Saturday, August 11, 2018 at 1:30 pm – 3:30 pm at the Watsonville- Santa Cruz JACL Tokushige Kizuka Hall, 150 Blackburn Street, Watsonville, CA 95076. This celebration is in conjunction with the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of August 10, 1988 by President Ronald W. -

Tokyo Rose Part 03 of 03

92 ._ I .' ' r La -.* '7u BEEAILS: ' At Wells, Cherokee County, Texas . t ji _ ' JACK KING WISNEY, former Postmaster in .'Iells, Post Office J5 . E Box lO5h, related that on June 13, 191.3, when he was a second lieutenant bombadier in the United States Army Air Force, flying orr a. B-1? Bomber out 1 of Port E.-ioresby, New Guinea, and while returning from a bombing mission over Rabaul, New Britian, and as he was en route back to his home base on Port Moresby about 3 AI. on the morning oi June 13, 19/43, the 1513119 011 Which he was acting nombadi-er was attacked by a Japanese night fighter. The plane was set afire, the pilot and copilot were killed, and the oxygen tank was damaged to the extent that it was necessary that he and the navigator "bail out". - ' 92 After landing in the parachute in the_jungle, "IIS192TER _.-' narrated that he endeavored to locate his companion, the bomber-navigator, but was unable to do so, and thereupon started working Southward througi the jungle and thus continued for approicirrsately nine days when he arrived at a plantation knom as the "TCRRIO PLAIIT;.TIC!-I", operated by a Dutchman. After arriving at the Pl&t1t"atiO!'1, the Dutchman and natives fed him, and then hid him in brush in a secluded spot on the Plantation. However, on June 21, 191-.3, T'I1LSI¬FR stated he was captured by a group of Japanese infantry- rnen and placed in a Japanese garrison on the plantation.