Cyclin Dependent Kinase 1-Dependent Activation of APC/C Ubiquitin Ligase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

List, Describe, Diagram, and Identify the Stages of Meiosis

Meiosis and Sexual Life Cycles Objective # 1 In this topic we will examine a second type of cell division used by eukaryotic List, describe, diagram, and cells: meiosis. identify the stages of meiosis. In addition, we will see how the 2 types of eukaryotic cell division, mitosis and meiosis, are involved in transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next during eukaryotic life cycles. 1 2 Objective 1 Objective 1 Overview of meiosis in a cell where 2N = 6 Only diploid cells can divide by meiosis. We will examine the stages of meiosis in DNA duplication a diploid cell where 2N = 6 during interphase Meiosis involves 2 consecutive cell divisions. Since the DNA is duplicated Meiosis II only prior to the first division, the final result is 4 haploid cells: Meiosis I 3 After meiosis I the cells are haploid. 4 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ Chromosomes condense. Because of replication during interphase, each chromosome consists of 2 sister chromatids joined by a centromere. ¾ Synapsis – the 2 members of each homologous pair of chromosomes line up side-by-side to form a tetrad consisting of 4 chromatids: 5 6 1 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ During synapsis, sometimes there is an exchange of homologous parts between non-sister chromatids. This exchange is called crossing over. 7 8 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis (2N=6) Prophase I: ¾ the spindle apparatus begins to form. ¾ the nuclear membrane breaks down: Prophase I 9 10 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, 4 Possible Metaphase I Arrangements: Metaphase I: ¾ chromosomes line up along the equatorial plate in pairs, i.e. -

Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy Alice Finardi 1, Lucia F. Massari 2 and Rosella Visintin 1,* 1 Department of Experimental Oncology, IEO, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, 20139 Milan, Italy; alice.fi[email protected] 2 The Wellcome Centre for Cell Biology, Institute of Cell Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3BF, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-5748-9859; Fax: +39-02-9437-5991 Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 5 August 2020; Published: 7 August 2020 Abstract: At each round of cell division, the DNA must be correctly duplicated and distributed between the two daughter cells to maintain genome identity. In order to achieve proper chromosome replication and segregation, sister chromatids must be recognized as such and kept together until their separation. This process of cohesion is mainly achieved through proteinaceous linkages of cohesin complexes, which are loaded on the sister chromatids as they are generated during S phase. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be fully removed at anaphase to allow chromosome segregation. Other (non-proteinaceous) sources of cohesion between sister chromatids consist of DNA linkages or sister chromatid intertwines. DNA linkages are a natural consequence of DNA replication, but must be timely resolved before chromosome segregation to avoid the arising of DNA lesions and genome instability, a hallmark of cancer development. As complete resolution of sister chromatid intertwines only occurs during chromosome segregation, it is not clear whether DNA linkages that persist in mitosis are simply an unwanted leftover or whether they have a functional role. -

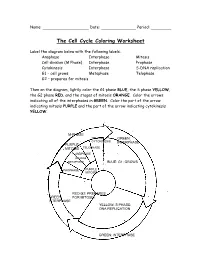

The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet

Name: Date: Period: The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet Label the diagram below with the following labels: Anaphase Interphase Mitosis Cell division (M Phase) Interphase Prophase Cytokinesis Interphase S-DNA replication G1 – cell grows Metaphase Telophase G2 – prepares for mitosis Then on the diagram, lightly color the G1 phase BLUE, the S phase YELLOW, the G2 phase RED, and the stages of mitosis ORANGE. Color the arrows indicating all of the interphases in GREEN. Color the part of the arrow indicating mitosis PURPLE and the part of the arrow indicating cytokinesis YELLOW. M-PHASE YELLOW: GREEN: CYTOKINESIS INTERPHASE PURPLE: TELOPHASE MITOSIS ANAPHASE ORANGE METAPHASE BLUE: G1: GROWS PROPHASE PURPLE MITOSIS RED:G2: PREPARES GREEN: FOR MITOSIS INTERPHASE YELLOW: S PHASE: DNA REPLICATION GREEN: INTERPHASE Use the diagram and your notes to answer the following questions. 1. What is a series of events that cells go through as they grow and divide? CELL CYCLE 2. What is the longest stage of the cell cycle called? INTERPHASE 3. During what stage does the G1, S, and G2 phases happen? INTERPHASE 4. During what phase of the cell cycle does mitosis and cytokinesis occur? M-PHASE 5. During what phase of the cell cycle does cell division occur? MITOSIS 6. During what phase of the cell cycle is DNA replicated? S-PHASE 7. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell grow? G1,G2 8. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell prepare for mitosis? G2 9. How many stages are there in mitosis? 4 10. Put the following stages of mitosis in order: anaphase, prophase, metaphase, and telophase. -

Patronus Is the Elusive Plant Securin, Preventing Chromosome Separation By

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/606285; this version posted April 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Patronus is the elusive plant securin, preventing chromosome separation by 2 antagonizing separase 3 Laurence Cromer1, Sylvie Jolivet1, Dipesh Kumar Singh1, Floriane Berthier1, Nancy 4 De Winne2, Geert De Jaeger2, Shinichiro Komaki3,4, Maria Ada Prusicki3, Arp 5 Schnittger3, Raphael Guérois5 and Raphael Mercier1* 6 7 1 Institut Jean-Pierre Bourgin, UMR1318 INRA-AgroParisTech, Université Paris- 8 Saclay, RD10, 78000 Versailles, France. 9 2 Department of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, Ghent, 10 Belgium, VIB Center for Plant Systems Biology, Ghent, Belgium 11 3 Department of Developmental Biology, Institute for Plant Sciences and 12 Microbiology, University of Hamburg, 22609 Hamburg, Germany. 13 4 Present address : Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Graduate School of 14 Biological Sciences, 8916-5 Takayama, Ikoma, Nara 630-0192, Japan 15 5 Institute for Integrative Biology of the Cell (I2BC), Commissariat à l’Energie 16 Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives (CEA), Centre National de la Recherche 17 Scientifique (CNRS), Université Paris-Sud, CEA-Saclay, Gif-sur-Yvette, France 18 * Corresponding author. [email protected] 19 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/606285; this version posted April 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Regulation of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Activity During Mitotic Exit and Maintenance of Genome Stability by P21, P27, and P107

Regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase activity during mitotic exit and maintenance of genome stability by p21, p27, and p107 Taku Chibazakura*†, Seth G. McGrew‡§, Jonathan A. Cooper§, Hirofumi Yoshikawa*, and James M. Roberts‡§ *Deparment of Bioscience, Tokyo University of Agriculture, 1-1-1 Sakuragaoka, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 156-8502, Japan; and ‡Howard Hughes Medical Institute and §Division of Basic Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA 98019 Communicated by Robert N. Eisenman, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, February 4, 2004 (received for review October 28, 2003) To study the regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity bind to and inactivate mitotic cyclin–CDK complexes (15, 16). during mitotic exit in mammalian cells, we constructed murine cell These CKIs accumulate and persist during mid-M-to-G1 phase ͞ lines that constitutively express a stabilized mutant of cyclin A until they are phosphorylated by Sic1 Rum1-resistant G1 cyclin- (cyclin A47). Even though cyclin A47 was expressed throughout CDKs, which initiates their ubiquitin-dependent degradation at mitosis and in G1 cells, its associated CDK activity was inactivated the G1-to-S phase transition (17–19). Thus, Sic1 and Rum1 after the transition from metaphase to anaphase. Cyclin A47 constitute a switch that controls the transition from a state of low associated with both p21 and p27 during mitotic exit, implicating CDK activity to that of high CDK activity, thereby regulating these proteins in CDK inactivation. However, cyclin A47 was fully mitotic exit and S phase entry. This parallels the activity of ؊/؊ ؊/؊ inhibited during the M-to-G1 transition in p21 p27 fibro- APC-Cdh1, and indeed these two pathways constitute redundant blasts. -

SAMBA, a Plant-Specific Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome Regulator Is Involved in Early Development and A-Type Cyclin Stabilization Nubia B

SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome regulator is involved in early development and A-type cyclin stabilization Nubia B. Eloy, Nathalie Gonzalez, Jelle van Leene, Katrien Maleux, Hannes Vanhaeren, Liesbeth de Milde, Stijn Dhondt, Leen Vercruysse, Erwin Witters, Raphaël Mercier, et al. To cite this version: Nubia B. Eloy, Nathalie Gonzalez, Jelle van Leene, Katrien Maleux, Hannes Vanhaeren, et al.. SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome regulator is involved in early de- velopment and A-type cyclin stabilization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , National Academy of Sciences, 2012, 109 (34), pp.13853 - 13858. 10.1073/pnas.1211418109. hal-01190736 HAL Id: hal-01190736 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01190736 Submitted on 29 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/ cyclosome regulator is involved in early development and A-type cyclin stabilization Nubia B. Eloya,b, Nathalie Gonzaleza,b, Jelle Van Leenea,b, Katrien Maleuxa,b, Hannes Vanhaerena,b, Liesbeth De Mildea,b, Stijn Dhondta,b, Leen Vercruyssea,b, Erwin Wittersc,d,e, Raphaël Mercierf, Laurence Cromerf, Gerrit T. -

Regulation of the Cell Cycle and DNA Damage-Induced Checkpoint Activation

RnDSy-lu-2945 Regulation of the Cell Cycle and DNA Damage-Induced Checkpoint Activation IR UV IR Stalled Replication Forks/ BRCA1 Rad50 Long Stretches of ss-DNA Rad50 Mre11 BRCA1 Nbs1 Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 Mre11 RPA MDC1 γ-H2AX DNA Pol α/Primase RFC2-5 MDC1 Nbs1 53BP1 MCM2-7 53BP1 γ-H2AX Rad17 Claspin MCM10 Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 TopBP1 CDC45 G1/S Checkpoint Intra-S-Phase RFC2-5 ATM ATR TopBP1 Rad17 ATRIP ATM Checkpoint Claspin Chk2 Chk1 Chk2 Chk1 ATR Rad50 ATRIP Mre11 FANCD2 Ubiquitin MDM2 MDM2 Nbs1 CDC25A Rad50 Mre11 BRCA1 Ub-mediated Phosphatase p53 CDC25A Ubiquitin p53 FANCD2 Phosphatase Degradation Nbs1 p53 p53 CDK2 p21 p21 BRCA1 Ub-mediated SMC1 Degradation Cyclin E/A SMC1 CDK2 Slow S Phase CDC45 Progression p21 DNA Pol α/Primase Slow S Phase p21 Cyclin E Progression Maintenance of Inhibition of New CDC6 CDT1 CDC45 G1/S Arrest Origin Firing ORC MCM2-7 MCM2-7 Recovery of Stalled Replication Forks Inhibition of MCM10 MCM10 Replication Origin Firing DNA Pol α/Primase ORI CDC6 CDT1 MCM2-7 ORC S Phase Delay MCM2-7 MCM10 MCM10 ORI Geminin EGF EGF R GAB-1 CDC6 CDT1 ORC MCM2-7 PI 3-Kinase p70 S6K MCM2-7 S6 Protein Translation Pre-RC (G1) GAB-2 MCM10 GSK-3 TSC1/2 MCM10 ORI PIP2 TOR Promotes Replication CAK EGF Origin Firing Origin PIP3 Activation CDK2 EGF R Akt CDC25A PDK-1 Phosphatase Cyclin E/A SHIP CIP/KIP (p21, p27, p57) (Active) PLCγ PP2A (Active) PTEN CDC45 PIP2 CAK Unwinding RPA CDC7 CDK2 IP3 DAG (Active) Positive DBF4 α Feedback CDC25A DNA Pol /Primase Cyclin E Loop Phosphatase PKC ORC RAS CDK4/6 CDK2 (Active) Cyclin E MCM10 CDC45 RPA IP Receptor -

Control of the Cell Cycle During Meiotic Maturation of Mouse Oocytes

Control of the cell cycle during meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes Ibtissem Nabti Department of Cell and Developmental Biology University College London London, UK A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2010 Declaration The work presented in this thesis was conducted under the supervision of Professor John Carroll in the department of cell and developmental biology, University College London, and Professor Keith Jones in the department of reproductive physiology, University of Newcastle upon Tyne. I, Ibtissem Nabti confirm that the data presented in this thesis is my own and from original studies. Also, this dissertation has not previously been submitted, wholly or in part, to any other university for any degree or diploma. Ibtissem Nabti 1 Abstract The overall aim of the work presented in this thesis is to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the progression of the meiotic division in mammalian oocytes. The first goal of this project was to investigate the relative contribution of securin and cyclin B1 to the control of the protease separase during the indeterminate period of metaphase II arrest. I found here that although there are conditions in which either securin or MPF can prevent chromosome disjunction, such as during meiosis I, securin is the predominant inhibitor of separase during metaphase II arrest. Thus, CDK1 pharmacological inhibition as well as antibody inhibition of CDK1/cyclin B1 binding to separase, both failed to induce sister chromatid disjunction. Instead, securin morpholino knockdown induced sister chromatid separation, which could be rescued by injection of securin cRNA. I also examined the effect of CDK1 and MAPK activities on securin stability. -

Meiosis I and Meiosis II; Life Cycles

Meiosis I and Meiosis II; Life Cycles Meiosis functions to reduce the number of chromosomes to one half. Each daughter cell that is produced will have one half as many chromosomes as the parent cell. Meiosis is part of the sexual process because gametes (sperm, eggs) have one half the chromosomes as diploid (2N) individuals. Phases of Meiosis There are two divisions in meiosis; the first division is meiosis I: the number of cells is doubled but the number of chromosomes is not. This results in 1/2 as many chromosomes per cell. The second division is meiosis II: this division is like mitosis; the number of chromosomes does not get reduced. The phases have the same names as those of mitosis. Meiosis I: prophase I (2N), metaphase I (2N), anaphase I (N+N), and telophase I (N+N) Meiosis II: prophase II (N+N), metaphase II (N+N), anaphase II (N+N+N+N), and telophase II (N+N+N+N) (Works Cited See) *3 Meiosis I (Works Cited See) *1 1. Prophase I Events that occur during prophase of mitosis also occur during prophase I of meiosis. The chromosomes coil up, the nuclear membrane begins to disintegrate, and the centrosomes begin moving apart. The two chromosomes may exchange fragments by a process called crossing over. When the chromosomes partially separate in late prophase, until they separate during anaphase resulting in chromosomes that are mixtures of the original two chromosomes. 2. Metaphase I Bivalents (tetrads) become aligned in the center of the cell and are attached to spindle fibers. -

The Spindle Checkpoint

Cell Science at a Glance 4139 The spindle checkpoint mechanism that delays anaphase onset highlight current understanding of how until all chromosomes are correctly the spindle checkpoint is activated, how it Karen M. May and Kevin G. attached in a bipolar fashion to the delays anaphase onset, and how it is Hardwick mitotic spindle. silenced. Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology, University of Edinburgh, EH9 3JR, UK The core spindle checkpoint proteins are (e-mail: [email protected]) Mad1, Mad2, BubR1 (Mad3 in yeast), Activation of the checkpoint Journal of Cell Science 119, 4139-4142 Bub1, Bub3 and Mps1. The Mad and Bub During mitosis spindle microtubules Published by The Company of Biologists 2006 proteins were first identified in budding bind to complex protein structures called doi:10.1242/jcs.03165 yeast by genetic screens for mutants that kinetochores, which assemble on the failed to arrest in mitosis when the spindle centromere of each chromosome. The Every mitosis, replicated chromosomes was destroyed (Taylor et al., 2004). These Mad and Bub proteins localise to the must be accurately segregated into each proteins are conserved in all eukaryotes. outer kinetochore early in mitosis, before daughter cell. Pairs of sister chromatids Several other checkpoint components, proper attachments are established, and attach to the bipolar mitotic spindle such as Rod, Zw10 and CENP-E, have accumulate on unattached kinetochores. during prometaphase, they are aligned at since been identified in higher eukaryotes When spindle microtubules make metaphase, then sisters separate and but have no yeast orthologues (Karess, contact with the outer kinetochore are pulled to opposite poles during 2005; Mao et al., 2003). -

APC/C-Cdh1-Dependent Anaphase and Telophase Progression During

Toda et al. Cell Division 2012, 7:4 http://www.celldiv.com/content/7/1/4 RESEARCH Open Access APC/C-Cdh1-dependent anaphase and telophase progression during mitotic slippage Kazuhiro Toda1, Kayoko Naito1, Satoru Mase1, Masaru Ueno1,2, Masahiro Uritani1, Ayumu Yamamoto1 and Takashi Ushimaru1* Abstract Background: The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) inhibits anaphase progression in the presence of insufficient kinetochore-microtubule attachments, but cells can eventually override mitotic arrest by a process known as mitotic slippage or adaptation. This is a problem for cancer chemotherapy using microtubule poisons. Results: Here we describe mitotic slippage in yeast bub2Δ mutant cells that are defective in the repression of precocious telophase onset (mitotic exit). Precocious activation of anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/ C)-Cdh1 caused mitotic slippage in the presence of nocodazole, while the SAC was still active. APC/C-Cdh1, but not APC/C-Cdc20, triggered anaphase progression (securin degradation, separase-mediated cohesin cleavage, sister- chromatid separation and chromosome missegregation), in addition to telophase onset (mitotic exit), during mitotic slippage. This demonstrates that an inhibitory system not only of APC/C-Cdc20 but also of APC/C-Cdh1 is critical for accurate chromosome segregation in the presence of insufficient kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Conclusions: The sequential activation of APC/C-Cdc20 to APC/C-Cdh1 during mitosis is central to accurate mitosis. Precocious activation of APC/C-Cdh1 in metaphase (pre-anaphase) causes mitotic slippage in SAC-activated cells. For the prevention of mitotic slippage, concomitant inhibition of APC/C-Cdh1 may be effective for tumor therapy with mitotic spindle poisons in humans.