Book of Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

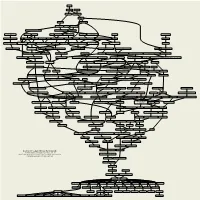

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

The Atheist's Bible: Diderot's 'Éléments De Physiologie'

The Atheist’s Bible Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie Caroline Warman In off ering the fi rst book-length study of the ‘Éléments de physiologie’, Warman raises the stakes high: she wants to show that, far from being a long-unknown draf , it is a powerful philosophical work whose hidden presence was visible in certain circles from the Revolut on on. And it works! Warman’s study is original and st mulat ng, a historical invest gat on that is both rigorous and fascinat ng. —François Pépin, École normale supérieure, Lyon This is high-quality intellectual and literary history, the erudit on and close argument suff used by a wit and humour Diderot himself would surely have appreciated. —Michael Moriarty, University of Cambridge In ‘The Atheist’s Bible’, Caroline Warman applies def , tenacious and of en wit y textual detect ve work to the case, as she explores the shadowy passage and infl uence of Diderot’s materialist writ ngs in manuscript samizdat-like form from the Revolut onary era through to the Restorat on. —Colin Jones, Queen Mary University of London ‘Love is harder to explain than hunger, for a piece of fruit does not feel the desire to be eaten’: Denis Diderot’s Éléments de physiologie presents a world in fl ux, turning on the rela� onship between man, ma� er and mind. In this late work, Diderot delves playfully into the rela� onship between bodily sensa� on, emo� on and percep� on, and asks his readers what it means to be human in the absence of a soul. -

Jean Meslier Düşüncesinde Ateizmin Temel Dayanakları Ve Eleştirisi

Jean Meslier Düşüncesinde Ateizmin Temel Dayanakları ve Eleştirisi Habib Şener Öz Tanrı inancına tepki olarak ortaya çıkmış olan ateizm, düşünce tarihindeki en önemli problemlerden birisidir. Ateist düşünceyi savunan Jean Meslier, 1664- 1729 yılları arasında yaşamış Fransız rahip ve filozoftur. 1689 yılında papazlık yapmaya başlayan Meslier, yaşadığı bazı sorunlardan dolayı sonradan ateist olmuştur. Başta Hıristiyanlık olmak üzere ilahî dinleri hedef alıp ateist iddialarını ortaya koymaya çalışmıştır. Onun ölümünden sonra yayımlanan ve Türkçe’ye Sağduyu adı ile çevrilmiş olan tek bir kitabı vardır. Bu çalışmada Meslier’in ateizme dayanak olarak ortaya koyduğu madde ve kötülük problemi hakkındaki görüşleri ele alınıp değerlendirilecektir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Tanrı, Teizm, Ateizm, Madde, Kötülük Problemi. Basics and Critique of Atheism in Jean Meslier's Thought Abstract Atheism, which has emerged as a reaction to the belief in God, is one of the most important problems in the history of thought. Jean Meslier, who defended the atheist idea, was a French priest and philosopher who lived between 1664-1729. Meslier started to be a priest in 1689 and later became an atheist because of some problems he experienced. He tried to reveal atheist claims by targeting the religions, especially Christianity. There is only one book published after his death, translated into Turkish with the name Sağduyu. In this work, Meslier's views on matter and the problem of evil which he put forward as a basis for atheism will be evaluated. Keywords: God, Theism, Atheism, Matter, The Problem of Evil. Yrd. Doç. Dr., Kafkas Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Felsefe ve Din Bilimleri Bölümü Öğretim Üyesi, e-mail: [email protected] Uludağ Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 27 (2018/1) 176▪ Habib Şener Giriş Tanrı inancı karşısında tepkisel bir düşünceyi dile getiren ateizm,1 Yunanca’da olumsuzluk bildiren “a” önekiyle, Tanrı anlamına gelen “theos”un birleşiminden meydana gelen ve Tanrı’nın var olmadığı inancına dayanan felsefî kavramdır. -

Jean Meslier and "The Gentle Inclination of Nature"

Jean Meslier and "The Gentle Inclination of Nature" translated by Marvin Mandell I. Of a Certain Jean Meslier HOW ASTONISHING that the prevailing historiography finds no place for an atheist priest in the reign of Louis XIV. More than that, he was a revolutionary communist and internationalist, an avowed materialist, a convinced hedonist, an authentically passionate and vindictively, anti-Christian prophet, but also, and above all, a philosopher in every sense of the word, a philosopher proposing a vision of the world that is coherent, articulated, and defended step by step before the tribunal of the world, without any obligation to conventional Western reasoning. Jean Meslier under his cassock contained all the dynamite at the core of the 18th century. This priest with no reputation and without any memorial furnishes an ideological arsenal of the thought of the Enlightenment's radical faction, that of the ultras, all of whom, drinking from his fountain, innocently pretend to be ignorant of his very name. A number of his theses earn for his borrowers a reputation only won by usurping his work. Suppressed references prevent the reverence due to him. His work? Just a single book, but what a book! A monster of more than a thousand manuscript pages, written with a goose quill pen under the glimmer of the fireplace and candles in an Ardennes vicarage between the so-called Great Century and the one following, called the Enlightenment, which he endorsed, by frequent use of the word, the sealed fate of the 18th century. A handwritten book, never published during the lifetime of its author, probably read by no one other than by its conceiver. -

El Estratonismo En El Materialismo Ilustrado: El Caso Sade Stratonism in Enlightenment Materialism: Sade

Daimon. Revista Internacional de Filosofía, en prensa, aceptado para publicación tras revisión por pares doble ciego. ISSN: 1130-0507 (papel) y 1989-4651 (electrónico) http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/daimon.423911 Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 España (texto legal). Se pueden copiar, usar, difundir, transmitir y exponer públicamente, siempre que: i) se cite la autoría y la fuente original de su publicación (revista, editorial y URL de la obra); ii) no se usen para fines comerciales; iii) se mencione la existencia y especificaciones de esta licencia de uso. El estratonismo en el materialismo ilustrado: el caso Sade Stratonism in Enlightenment materialism: Sade NATALIA L. ZORRILLA1 Resumen Este artículo tiene como objetivo estudiar el proceso de articulación del “estratonismo”, constructo histórico-filosófico creado en torno a la figura de Estratón de Lámpsaco, en la Ilustración francesa. Argumentaremos que el materialismo ateo ilustrado incorpora elementos estratonistas, centralmente la idea de la naturaleza como potencia productiva ciega. Nos abocaremos a reconstruir tal proceso de articulación, concentrándonos en la obra de autores de posiciones diversas (incluso opuestas entre sí) como Cudworth, Bayle y d’Holbach. Examinaremos a continuación la reapropiación crítica del estratonismo que realiza Braschi, uno de los personajes filósofos de la obra Histoire de Juliette de Sade, en su cosmovisión materialista atea. Palabras clave: Estratonismo; Materialismo ateo; Ilustración francesa; Bayle; Sade. Abstract This article aims at studying the emergence of “stratonism”, a historical and philosophical construct created around Strato of Lampsacus’s figure and ideas, in the French Enlightenment. The paper argues that Enlightenment atheist materialism embraces diverse stratonist elements, mainly the idea of nature as blind productive power. -

A Leibnizian Approach to Mathematical Relationships: a New Look at Synthetic Judgments in Mathematics

A Thesis entitled A Leibnizian Approach to Mathematical Relationships: A New Look at Synthetic Judgments in Mathematics by David T. Purser Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy ____________________________________ Dr. Madeline M. Muntersbjorn, Committee Chair ____________________________________ Dr. John Sarnecki, Committee Member ____________________________________ Dr. Benjamin S. Pryor, Committee Member ____________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2009 An Abstract of A Leibnizian Approach to Mathematical Relationships: A New Look at Synthetic Judgments in Mathematics by David T. Purser Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy The University of Toledo May 2010 I examine the methods of Georg Cantor and Kurt Gödel in order to understand how new symbolic innovations aided in mathematical discoveries during the early 20th Century by looking at the distinction between the lingua characterstica and the calculus ratiocinator in the work of Leibniz. I explore the dynamics of innovative symbolic systems and how arbitrary systems of signification reveal real relationships in possible worlds. Examining the historical articulation of the analytic/synthetic distinction, I argue that mathematics is synthetic in nature. I formulate a moderate version of mathematical realism called modal relationalism. iii Contents Abstract iii Contents iv Preface vi 1 Leibniz and Symbolic Language 1 1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………. 1 1.2 Universal Characteristic……………………………………….. 4 1.2.1 Simple Concepts……………………………………….. 5 1.2.2 Arbitrary Signs………………………………………… 8 1.3 Logical Calculus………………………………………………. 11 1.4 Leibniz’s Legacy……………………………………………… 16 1.5 Leibniz’s Continued Relevance………………………………. -

Programme RE2013

Programme ‘The Radical Enlightenment: The Big Picture and its Details’ Universitaire Stichting, Egmontstraat 11, 1000 Brussels May 16-17 2013 Thursday 16 May 2013 8.20-8.55 a.m. Welcome and registration (with coffee) 8.55 a.m.-12.15 p.m. Morning session 8.55-9.00 a.m. Opening conference: Steffen Ducheyne (Room A) 9.00-10.00 a.m. Keynote lecture I Jonathan I. Israel (Room A): Radical Enlightenment: Monism and the Rise of Modern Democratic Republicanism 10.00-11.00 a.m. Keynote lecture II Wiep van Bunge (Room A): The Waning of the Radical Enlightenment in the Dutch Republic 11.00-11.15 a.m. Coffee break 11.15 a.m.-12.15 p.m. Keynote lecture III Else Walravens (Room A): The Radicality of Johann Christian Edelmann: A Synthesis of Progressive Enlightenment, Pluralism and Spiritualism 12.15-2.00 p.m. Lunch break 2.00-6.15 p.m. Afternoon session 2.00-3.30 p.m. Parallel session I Room A: Anya Topolski : Tzedekah : The True Religion of Spinoza’s Tractatus Jetze Touber: The Temple of Jerusalem in Picture and Detail: Biblical Antiquarianism and the Construction of Radical Enlightenment in the Dutch Republic, 1670-1700 Ian Leask : John Toland’s Origines Judaicae : Speaking for Spinoza? Room B: Ultán Gillen : Radical Enlightenment and Revolution in 1790s Ireland: The Ideas of Theobald Wolfe Tone Sonja Lavaert : Radical Enlightenment, Enlightened Subversion, and the Reversal of Spinoza Julio Seoane-Pinilla : Sade, Sex and Transgression in Eighteenth- century Philosophy 3.30-5.00 p.m. Parallel session II Room A: Falk Wunderlich : Late Enlightenment Materialism in Germany: The Case of Christoph Meiners and Michael Hißmann Paola Rumore : Between Spinozism and Materialism: Buddeus’ Place in the Early German Enlightenment Arnaud Pelletier : H ow much Radicality can the Enlightenment tolerate? The Case of Gabriel Wagner ( Realis de Vienna ) Reconsidered Room B: Vasiliki Grigoropoulou : Radical Consciousness in Spinoza and the Case of C. -

Paola Rumore

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Research Information System University of Turin Paola Rumore In Wolff’s Footsteps. The Early German Reception of La Mettrie’s L’Homme machine 1. A specter personified At the end of 1747, when L’Homme machine began to circulate, the German philosophical scene was entering into a temporary truce in its long-lasting strug- gle against materialism, at that point still considered the most harmful and the disgraceful expression of free-thinking. This situation concerned mainly that large part of Germany, which had remained almost uncontaminated by the new Francophile trend that animated the cultural enclave of Frederick’s court in Berlin. In fact, according to one of the most authoritative interpreters of 18th century German philosophy, “the French Enlightenment had surely caused some disturbance in Sanssouci, but its resonance in the surrounding German world remained limited”1. The publication of L’Homme machine, often described as a “monument of disgrace and ignominy”2, forced Germany to face once again the phantom of materialism, which now appeared in the form of a real danger in a well-delineated shape, no longer a vague, undefined, and somehow spectral threat. The degree of reality of the current menace of materialism was also in- creased by the fact that the author of the book had been warmly welcomed at the Prussian court; L’Homme machine was not one of the usual phantomatic foreign dangers pressing up against the borders of the kingdom, but a real presence on German soil. -

Le Testament by Jean Meslier: the Pioneering Work of the Militant Atheism in France

STUDIA HISTORICA GEDANENSIA TOM VII (2016) Aleksandra Porada (SWPS University of Social Sciences) Le Testament by Jean Meslier: the Pioneering Work of the Militant Atheism in France The ongoing debate of the ‘laicization’ of the Western intellectual production during the Enlightenment seems to be far from being closed. Still, we cannot deny that the attitudes towards both the ecclesiastical institutions and Christian beliefs in Western Europe started to change in the end of the 17th c. In France, one of the centers of the intellectual life of the West, the process called ‘dechris‑ tianization’ was manifest at many levels – beginning from the peasants becoming less generous in paying for masses when losing a relative, up to the disputes of intellectuals about delicate questions of theology. Paradoxically, the most radical thinker of the epoch, Jean Meslier (1664– 1729), remains relatively little known even to the historians of ideas. His life remains rather obscure, for he was just a modest priest working all his life in a village; his work seems to have been far too radical to be printed in an unabridged version till mid‑19th c., but also simply too long to be read by more than a handful of students. And yet, Meslier’s Testament deserves to be studied closely. It is the first known treaty about the non‑existence of God in the French language, and a classic of materialist philosophy as well; and an uncompromis‑ ing attack on religious institutions followed by a radically new vision of an egalitarian society which made Meslier a pioneer of both atheist and commu‑ nist thought. -

Twelve Tribes Under God “The Jewish Roots of Western Freedom” by Fania Oz-Salzberger, in Azure (Summer 2002), 22A Hatzfira St., Jerusalem, Israel

The Periodical Observer conquered lands were never required to sur- gained a foothold in Italy when he died in the render their property—or their faith. late 15th century; Suleiman the Magnificent Each successive Crusade was better fund- failed to take Vienna in 1529 only because ed and organized, yet each was less effective freak rainstorms forced him to abandon than the one before it. By the 15th and 16th much of his artillery. centuries, “the Ottoman Turks [had] con- The real field of battle, meanwhile, was quered not only their fellow Muslims, thus fur- shifting from the military realm to industry, ther unifying Islam, but also continued to science, and trade. With the Renaissance press westward, capturing Constantinople and then the Protestant Reformation, and plunging deep into Europe itself.” European civilization entered a new era of Only happenstance prevented Islam from dynamism, and the balance of power shifted moving farther west: Sultan Mehmed II had decisively to the West. Twelve Tribes under God “The Jewish Roots of Western Freedom” by Fania Oz-Salzberger, in Azure (Summer 2002), 22A Hatzfira St., Jerusalem, Israel. Ask a political theorist to name the histor- famous commitment to the “pursuit of life, ical foundations of Western liberalism, and the liberty, and property,” Oz-Salzberger reply will be predictable: the polis of Athens, asserts, was grounded in a theory of respon- the Roman Republic, the Magna Carta, etc. sibility and charity drawn from the Bible. Few are likely to mention the Torah—the first These philosophers tended to find in the five books of the Hebrew Bible—or the ancient “Hebrew Republic” an example that Talmud. -

Foundations of Psychology by Herman Bavinck

Foundations of Psychology Herman Bavinck Translated by Jack Vanden Born, Nelson D. Kloosterman, and John Bolt Edited by John Bolt Author’s Preface to the Second Edition1 It is now many years since the Foundations of Psychology appeared and it is long out of print.2 I had intended to issue a second, enlarged edition but the pressures of other work prevented it. It would be too bad if this little book disappeared from the psychological literature. The foundations described in the book have had my lifelong acceptance and they remain powerful principles deserving use and expression alongside empirical psy- chology. Herman Bavinck, 1921 1 Ed. note: This text was dictated by Bavinck “on his sickbed” to Valentijn Hepp, and is the opening paragraph of Hepp’s own foreword to the second, revised edition of Beginselen der Psychologie [Foundations of Psychology] (Kampen: Kok, 1923), 5. The first edition contains no preface. 2 Ed. note: The first edition was published by Kok (Kampen) in 1897. Contents Editor’s Preface �����������������������������������������������������������������������ix Translator’s Introduction: Bavinck’s Motives �������������������������� xv § 1� The Definition of Psychology ���������������������������������������������1 § 2� The Method of Psychology �������������������������������������������������5 § 3� The History of Psychology �����������������������������������������������19 Greek Psychology .................................................................19 Historic Christian Psychology ..............................................22 -

In the Hebrew Bible

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/01916599.2018.1513249 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Stökl, J. (2018). ‘Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land unto All the Inhabitants Thereof!’: Reading Leviticus 25:10 Through the Centuries. History of European Ideas, 44(6), 685-701. https://doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2018.1513249 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim.