Introduction – 'The Beginnings'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site

The Culture of Memory and the Role of Archaeology: A Case Study of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest and the Kalkriese Archaeological Site Laurel Fricker A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 18, 2017 Advised by Professor Julia Hell and Associate Professor Kerstin Barndt 1 Table of Contents Dedication and Thanks 4 Introduction 6 Chapter One 18 Chapter Two 48 Chapter Three 80 Conclusion 102 The Museum and Park Kalkriese Mission Statement 106 Works Cited 108 2 3 Dedication and Thanks To my professor and advisor, Dr. Julia Hell: Thank you for teaching CLCIV 350 Classical Topics: German Culture and the Memory of Ancient Rome in the 2016 winter semester at the University of Michigan. The readings and discussions in that course, especially Heinrich von Kleist’s Die Hermannsschlacht, inspired me to research more into the figure of Hermann/Arminius. Thank you for your guidance throughout this entire process, for always asking me to think deeper, for challenging me to consider the connections between Germany, Rome, and memory work and for assisting me in finding the connection I was searching for between Arminius and archaeology. To my professor, Dr. Kerstin Barndt: It is because of you that this project even exists. Thank you for encouraging me to write this thesis, for helping me to become a better writer, scholar, and researcher, and for aiding me in securing funding to travel to the Museum and Park Kalkriese. Without your support and guidance this project would never have been written. -

The Rise of the German Menace

The Rise of the German Menace Imperial Anxiety and British Popular Culture, 1896-1903 Patrick Longson University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Doctoral Thesis for Submission to the School of History and Cultures, University of Birmingham on 18 October 2013. Examined at the University of Birmingham on 3 January 2014 by: Professor John M. MacKenzie Professor Emeritus, University of Lancaster & Professor Matthew Hilton University of Birmingham Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Before the German Menace: Imperial Anxieties up to 1896 25 Chapter 2 The Kruger Telegram Crisis 43 Chapter 3 The Legacy of the Kruger Telegram, 1896-1902 70 Chapter 4 The German Imperial Menace: Popular Discourse and British Policy, 1902-1903 98 Conclusion 126 Bibliography 133 Acknowledgments The writing of this thesis has presented many varied challenges and trials. Without the support of so many people it would not have been possible. My long suffering supervisors Professor Corey Ross and Dr Kim Wagner have always been on hand to advise and inspire me. They have both gone above and beyond their obligations and I must express my sincere thanks and lasting friendship. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Eric Axelson. Vasco da Gamma: The Diary of His ices will discover it to be an enjoyable, accessible, Travels Through African Waters, 1497-1499. and engaging account. It is certainly a good buy Somerset West, South Africa: Stephan Phillips for most research or university libraries. (Pty) Ltd., 1998. vii + 102, notes, appendices, bibliography, maps, illustrations. ISBN 0-620- M.A. Hennessy 22388-x. Kingston, Ontario Eric Axelson, former head of the Department of History at the University of Cape Town, is to be L.M.E. Shaw. The Anglo-Portuguese Alliance commended for producing a richly illustrated and and the English Merchants in Portugal, 1654- comprehensive new translation of this diary. 1810. Aldershot, Hants. & Brookfield, VT: Translations or the Portuguese original have been Ashgate Publishing, 1998. xii + 233 pp., maps, published previously in 1898,1947 and 1954. The photoplates, appendices, bibliography, index. US last of these, African Explorers (Oxford, 1954), $76.95, cloth; ISBN 1-84014-651-6. was also edited by Axelson, but it did not address the voyage from the coast of Mozambique to This work marks a further contribution by Dr. India and back. That shortfall has been avoided in Shaw to Anglo-Portuguese history in the seven• this valuable new edition, which also contains teenth and eighteenth centuries, significantly other useful features. developing her earlier studies, among them her The anonymous diary commences with da notable investigation into the serious effects of the Gamma's ship leaving Portugal and ceases some• inquisition on Portuguese mercantile wealth and where off Gabon - Axelson addresses why this is resources. -

Shapero RARE BOOKS Shapero Rare Books 1

2017 BAEDEKER’S & GENERAL TRAVEL GUIDES Shapero RARE BOOKS Shapero Rare Books 1 BAEDEKER’S & GENERAL TRAVEL GUIDES 2017 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA Tel: +44 207 493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com Contents Baedeker’s English Editions 03 - 16 Baedeker’s French Editions 17 - 23 Baedeker’s German Editions 24 - 49 Murray’s Handbooks 50 - 62 Miscellaneous Guides 63 - 70 New Publications 71 BAEDEKER’S ENGLISH EDITIONS 1. Belgium and Holland. some wear to the spine, “Brentano price list” Karl Baedeker, Leipsic,1881. pasted down on endpapers; a good copy. Endpapers dated “January 1881”. £100 [78872] Hinrichsen E185. Sixth edition. lxii, 338pp, 8 maps and 18 plans, 5. Canada with Newfoundland and an ink writing on preliminaries and title-page, inner Excursion to Alaska. hinges cracked, spine worn and rubbed at top Karl Baedeker, Leipzig, 1922. and bottom. Last edition of this title. A map of the Rocky £60 [50848] mountains has been added. Issued c.1938. Hinrichsen E266. 2. Belgium and Luxemburg. Fourth edition. lxx, 420pp, 14 maps and 12 Karl Baedeker, Leipzig. 1931. plans, previous bookseller’s label pasted down on Last English title covering Belgium. Holland front free endpaper, publisher’s red cloth gilt; a is no longer included and the section on very good copy with gilt lettering bright. Luxemburg has been extended. Issued c.1931. £150 [94004] Hinrichsen E195. Sixteenth edition. xliv, 366pp, 43 maps and 6. Eastern Alps including the Bavarian plans, publisher’s red cloth gilt, original pictorial Highlands, Tyrol , Salzburg, Upper and Lower dust jacket; a very good copy. -

Tschirnitz 1874 - Dresden 1954

Richard MULLER (Tschirnitz 1874 - Dresden 1954) Study of the Hermann Monument Black chalk, with stumping. Signed, dated and inscribed Rich. Müller / Hermanns Denkmal Teutoburger Wald 26.8.17 at the bottom. 173 x 147 mm. (6 4/5 x 5 3/4 in.) Drawn on 26th of August 1917, this drawing depicts the Hermannsdenkmal, or Hermann Monument, in the Teutoburg Forest in the German province of North Rhine-Westphalia. Seen here from its base, the colossal statue is dedicated to Arminius (later translated into German as Hermann), the war chief of the Cherusci tribe, who led an alliance of Germanic clans that defeated three Roman legions in battle in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD. A prince of the Cherusci people, as a child Arminius was sent as a hostage to Rome, where he was raised. He joined the Roman army and eventually became a Roman citizen. Sent to Magna Germania to aid the Roman general Publius Quinctilius Varus in his subjugation of the Germanic peoples, Arminius secretly formed an alliance of the Cherusci with five other Germanic tribes. He used his knowledge of Roman military tactics to lead Varus’s forces into an ambush, resulting in the complete annihilation of the XVII, XVIII and XIX legions, with the loss of between 15,000 and 20,000 Roman soldiers. Generally regarded by historians as Rome’s greatest military defeat, and one of the most decisive military engagements of all time, Arminius’s victory in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest precipitated the Roman empire’s eventual strategic withdrawal from Germania and prevented its expansion east of the Rhine. -

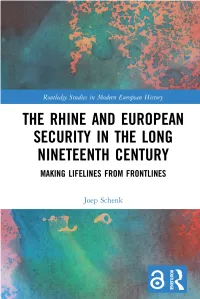

Making Lifelines from Frontlines; 1

The Rhine and European Security in the Long Nineteenth Century Throughout history rivers have always been a source of life and of conflict. This book investigates the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine’s (CCNR) efforts to secure the principle of freedom of navigation on Europe’s prime river. The book explores how the most fundamental change in the history of international river governance arose from European security concerns. It examines how the CCNR functioned as an ongoing experiment in reconciling national and common interests that contributed to the emergence of Eur- opean prosperity in the course of the long nineteenth century. In so doing, it shows that modern conceptions and practices of security cannot be under- stood without accounting for prosperity considerations and prosperity poli- cies. Incorporating research from archives in Great Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands, as well as the recently opened CCNR archives in France, this study operationalises a truly transnational perspective that effectively opens the black box of the oldest and still existing international organisation in the world in its first centenary. In showing how security-prosperity considerations were a driving force in the unfolding of Europe’s prime river in the nineteenth century, it is of interest to scholars of politics and history, including the history of international rela- tions, European history, transnational history and the history of security, as well as those with an interest in current themes and debates about transboundary water governance. Joep Schenk is lecturer at the History of International Relations section at Utrecht University, Netherlands. He worked as a post-doctoral fellow within an ERC-funded project on the making of a security culture in Europe in the nineteenth century and is currently researching international environmental cooperation and competition in historical perspective. -

Ian Bartholomew

Ian Bartholomew Theatre Title Role Director Producer Half A Sixpence Chitterlow Rachel Kavanaugh Noel Coward Theatre & Chichester Festival Theatre The Funfair Billy Smoke Walter Meierjohann Home: Manchester Mrs Henderson Presents Vivian Van Damm Terry Johnson HRH Theatres Shakespeare in Love Tilney Declan Donellan Disney Richard III Richard Loveday Ingham Nottingham Playhouse & York Theatre Royal Oh! What a Lovely War Hague and Various Terry Johnson Theatre Royal Stratford East Follow the Star Lofty Wendy Toye Chichester Festival A Night in Old Peking Jack Martin Duncan Lyric Hammersmith School for Scandal Joseph Surface Phyllida Lloyd Royal Exchange Sleeping Beauty Helpful 2 Philip Hedley Theatre Royal, Stratford School for Clowns Weasle Martin Duncan Lillian Baylis Servant of 2 Masters Truffaldino Martin Duncan Cambridge Theatre Diary of a Somebody Kenneth Halliwell Jonathan Myerson Kings Head Theatre Skullduggery Chris Philip Davis Old Red Lion Cinderella Buttoms Philip Hedley Theatre Royal, Stratford Kooney Waka Hoy Nijinsky Old Red Lion Robert Longdon Winter Darkness Boysey Susan Hogg New End Theatre Pravda Doug Phantom David Hare National Theatre The Artists Partnership 21-22 Warwick Street, Soho, London W1B 5NE (020) 7439 1456 Futurists Bruichkov Richard Eyre National Theatre The Gov't Inspector Dobchinsky Richard Eyre National Theatre Schweyck in the 2nd WW Soldier & Others Richard Eyre National Theatre Guys and Dolls Society Max Richard Eyre National Theatre The Beggars Opera Ben Budge Richard Eyre National Theatre Mayakovsky: -

Download Three Men in a Boat, Jerome K. Jerome, Penguin Adult, 2004

Three Men in a Boat, Jerome K. Jerome, Penguin Adult, 2004, 0141441216, 9780141441214, 224 pages. A comic masterpiece that has never been out of print since it was first published in 1889, Jerome K. Jerome's Three Men in a Boat includes an introduction and notes by Jeremy Lewis in Penguin Classics. Martyrs to hypochondria and general seediness, J. and his friends George and Harris decide that a jaunt up the Thames would suit them to a 'T'. But when they set off, they can hardly predict the troubles that lie ahead with tow-ropes, unreliable weather forecasts and tins of pineapple chunks - not to mention the devastation left in the wake of J.'s small fox-terrier Montmorency. Three Men in a Boat was an instant success when it appeared in 1889, and, with its benign escapism, authorial discursions and wonderful evocation of the late-Victorian 'clerking classes', it hilariously captured the spirit of its age. In his introduction, Jeremy Lewis examines Jerome K. Jerome's life and times, and the changing world of Victorian England he depicts - from the rise of a new mass-culture of tabloids and bestselling novels to crazes for daytripping and bicycling. Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927) was born in Walstall, Staffordshire, and educated at Marylebone Grammar School. He left school at fourteen to become a railway clerk, the first in a long line of jobs that included actor, teacher and journalist. His first book, On Stage and Off, a collection of humorous pieces about the theatre, was published in 1885, and was followed the year after with the more commercially-successful The Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow; but it was with Three Men in a Boat (1889) that Jerome achieved lasting fame. -

On the Symbolic Coping with the Fragility of Partner Relationships by Means of Padlocking

Volume 17, No. 2, Art. 4 May 2016 An Ever-Fixed Mark? On the Symbolic Coping With the Fragility of Partner Relationships by Means of Padlocking Kai-Olaf Maiwald Key words: Abstract: "Padlocking" is a quite recent phenomenon observable in many major cities in Europe padlocking; couple and throughout the world. Couples engrave their initials or names on a padlock, fix it in a public relationships; place, preferably bridges, and throw the keys away. Locations like the Hohenzollern Bridge in relationship status; Cologne, Germany, have become a hotspot for this practice, with thousands and thousands of symbolism; padlocks covering the grids of the banisters. But what kind of practice is it that we are dealing with romantic practices; here? With an objective-hermeneutic approach, the symbolic meaning of the "love lock" and the artifact analysis; practice involved is disclosed. Compared to common, legal practices of institutionalizing couple objective relationships, padlocking seems to explicitly accommodate the fragility of romantic attachments. In hermeneutics this, it is an attempt to perpetuate the feeling of being in love. Table of Contents 1. What is "Padlocking"? 2. Cracking the Symbolic Meaning of the Padlock 3. Padlocks and the Status of Partner Relationship 4. Symbolic Meaning and the Risk of Separation 5. The Love of Love 6. Padlocking as "Emotion Work"? Acknowledgments References Author Citation This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research (ISSN 1438-5627) FQS 17(2), Art. 4, Kai-Olaf Maiwald: An Ever-Fixed Mark? On the Symbolic Coping With the Fragility of Partner Relationships by Means of Padlocking 1. -

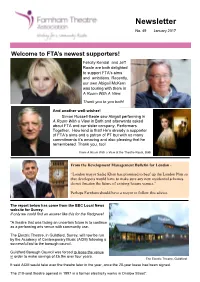

Newsletter No

Newsletter No. 49 January 2017 Welcome to FTA’s newest supporters! Felicity Kendal and Jeff Rawle are both delighted to support FTA‟s aims and ambitions. Recently, our own Abigail McKern was touring with them in A Room With A View. Thank you to you both! And another well-wisher! Simon Russell-Beale saw Abigail performing in A Room With a View in Bath and afterwards asked about FTA and our sister company, Performers Together. How kind is that! He‟s already a supporter of FTA‟s aims and a patron of PT but with so many commitments it‟s amazing and also pleasing that he remembered. Thank you, too! From A Room With a View at the Theatre Royal, Bath From the Development Management Bulletin for London - “London mayor Sadiq Khan has promised to beef up the London Plan so that developers would have to make sure any new residential schemes do not threaten the future of existing leisure venues.” Perhaps Farnham should have a mayor to follow this advice. The report below has come from the BBC Local News website for Surrey. If only we could find an answer like this for the Redgrave! "A theatre that was facing an uncertain future is to continue as a performing arts venue with community use. The Electric Theatre, in Guildford, Surrey, will now be run by the Academy of Contemporary Music (ACM) following a successful bid to the borough council. Guildford Borough Council was forced to lease the venue in order to make savings of £6.9m over four years. -

Recovery of Acetylcholinesterase at Intact Neuromuscular Junctions After in Viva Inactivation with Di-Isopropylfluorophosphate’

0270.8474/85/0504-0951$02.00/O The Journal of Neuroscience Copyright 0 Society for Neuroscience Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 951-955 Printed in U.S.A. April 1985 Recovery of Acetylcholinesterase at Intact Neuromuscular Junctions After In Viva Inactivation with Di-isopropylfluorophosphate’ HEDWIG KASPRZAK* AND MIRIAM M. SALPETER* * Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 and *Section of Neurobiology and Behavior, and School of Applied and Engineering Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 Abstract Materials and Methods Recovery of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) at endplates of Animal preparations for inactivating esterases. We used the sternomas- toid muscle of the albino mouse (obtained from Blue Spruce Farms). Receptor mouse sternomastoid muscle was studied after inactivation and esterase inactivation was performed as previously described by Fertuck with di-isopropylfluorophosphate in viva. A short incubation et al. (1975) Fertuck and Salpeter (1976) and Salpeter et al. (1979). Animals with a-bungarotoxin was used to prevent muscle necrosis were anesthetized with Nembutal (50 mg in 10% alcohol/kg of body weight). which usually occurs after esterase inactivation. Under these The muscle was exposed and the nerve was stimulated with a suction conditions there was no delay in AChE recovery, unlike what electrode while muscle contractions were monitored with a needle electrode we had previously seen in necrotic muscle. However, even attached to an isotonic transducer. The exposed muscle was first bathed in in non-necrotic muscle, the overall recovery of AChE at the ol-BTX (lo+ M in Krebs’ Ringer Solution) until the receptors were completely postjunctional membrane was very slow, with a half-life of inactivated as judged by the fact that the muscle was unable to produce a about 20 days.