A Conversation with Judge Horace Ward: Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

Web Site Brochure.Indd

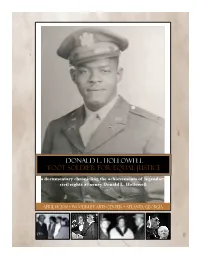

Donald L. Hollowell Foot Soldier for Equal Justice a documentary chronicling the achievements of legendary civil rights attorney Donald L. Hollowell April 15, 2010 * Woodruff Arts Center * Atlanta, Georgia [ Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Esq. Maurice C. Daniels, Dean and Professor Endowment Committee Chairman University of Georgia School of Social Work I finished law school the first I have been a member of the Friday in June 1960. The Monday faculty of the University of morning after I graduated, I went Georgia for more than 25 to work for Donald Hollowell for years. My tenure here was made $35 a week. I was his law clerk possible because of the courage, and researcher, and I carried his commitment, and brilliance of briefcase and I was his right-hand Donald Hollowell. Therefore, I man. He taught me how to be am personally and professionally a lawyer, a leader, how to fight committed to continuing Mr. injustice. Whatever I have become Hollowell’s legacy as a champion in the years, I owe it to him in for the cause of social justice. large measure. — Maurice C. Daniels — Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. Dear Colleagues and Friends, To commemorate and continue the legacy of Donald L. Hollowell, one of our nation’s greatest advocates for social justice, the University of Georgia approved the establishment of the Donald L. Hollowell Professorship of Social Justice and Civil Rights Studies in the School of Social Work. Donald L. Hollowell was the leading civil rights lawyer in Georgia during the 1950s and 1960s. He was the chief architect of the legal work that won the landmark Holmes v. -

Seventy-Sixth Founders' Day at Morris Brown College

VOLUME 31 MORRIS BROWN COLLEGE, ATLANTA, GA., MARCH-APRIL, 1961 Number 4 Seventy-Sixth Founders’ Day At Morris Brown College (Edited By DONALD J. WILSON) The prominent Bishop E. C. Hatcher of Ohio spoke in eloquent Farm, Americus, Georgia; Morris fashion at Morris Brown College as he told the enthusiastic Founders’ Brown College — the Reverend Day audience that Morris Brown was founded to meet the great need Frederick C. James, Sumter, South for undergirding our American education with religious training. This Carolina, Director of the Commit was the 76th observance of the school’s Founders’ Day. Bishop Wilkes tee of Social Action, The African presented the speaker to the audience and the President, Frank Cun Methodist Episcopal Church; and Spelman College — the Reverend ningham presided over the program. Others on the program were Mary William Bell Glenesk, Spencer Me Ann Smith, senior student who brought an inspiring greeting from the morial Presbyterian Church, student body; A. L. Jessie, who gave a progress report on the Alumni Brooklyn, New York. Fund; Dr. H. I. Bearden, Dr. A. L. Harris of Augusta, and Dr. James A committee, whose chairman Debro of the Albany district Also the Bishop S. L. Green, senior bishop was Dr. Frank Cunningham, Presi and several other church notables were presented to the audience. dent of Morris Brown College, was The speaker, Bishop Hatcher, in charge of the affairs of the Re tied in the history of Morris Brown ligious Emphasis Week. The com A Salute For Courage mittee was composed of people with the Negro’s struggle for free from all the schools of the Center. -

Is Named Separate but Equal ^Clinton Principal by Dallas Democrats

FEATURES PICTURES ARTICLES VOLUME 26? NUMBER 13 Jackie Robinson Urges Unity, Vigorous Action As Steps To Full Rights As Race RY RAYMOND F. TISBY I Have io live, with niyseli',’’ Robiii- Robinson. former Brooklyn Dod son said. ger star and now serving as nation Urging unified racial action and a al chairman of the N. A. A. C. P. vigorous fight for full citizenship, 1957 Freedom Fund, told an audi Robinson believed "the Negro should ence of between 3,500 and 4,000 in do everything in his power, short Mason Temple, 938 S. Mason, that of violence, to attain first class "our success depends on our work citizenship. The only thing I want ing together as a unit.”. as a Negro are tire rights deserv Believing that now is our greatest edly mine-’under tile ¡Cohstitutiphi'i opportunity,” the 38-year-old base Will Represent U. S. Govt. ball pioneer, urged all Negroes to Others appearing on the program were Gloster Current, national N. A. join- and suport the N.A.~A. C. P. that, “represents everything that is A- C. P. director of branches, and Mrs. D.-ilsy Lampkin, vice, president In Interest Of New Nation democratic in this country.” of that Pittsburgh Courier nnd na - Robinson, the recipient of the tional N. A. A. C. P. membership BY WILLIAM tHEiS N. A. A. C- P.’s 1956 Spingarm drive chairman. Medal, felt that the "full story” oi CASABLANCA, Morocco — (INS) — Vice Presidenl Richard M7 Memphlslans appearing on the the N A. A. C, p. has not been I Nixon said Saturday that any danger that the U, SiUflight .lot*. -

College Bulletin

mopehouse college Bulletin ©1979FM Alumni Contributions and Morehouse A Morehouse alumnus was heard to tion had fallen on his shoulders—if the alumnus who gives $1,000 each year. Each make this statement: "I don't owe More¬ total cost of constructing and maintaining is giving according to his ability. Each is house a thing. I paid my way through col¬ buildings, buying and maintaining equip¬ helping to alleviate the financial burdens so I see lege, don't why I should give ment, finding and keeping top-notch of the College. For this reason the anything to Morehouse.'' teachers had been his responsibility. If all smallest gift is gratefully received. For A second alumnus was heard to of these say, "I costs were added together and this reason it is difficult to find a know I have an obligation to make a con¬ divided equally among all Morehouse Morehouse man whose circumstances tribution to Morehouse, but I am embar¬ students enrolled during a particular year, will not permit him to make even a small rassed to give a small amount. I really very few (if any) would survive the first contribution IT IS THE HABIT OF GIV¬ want to respond to those letters I get from month. The individual cost would be pro¬ ING TO MOREHOUSE EACH YEAR President Gloster. But since I am in no hibitive. Only because of gifts that come WHICH IS THE MOST IMPORTANT position to give as much as I would like to from friends and alumni can a private col¬ THING. give, I just don't send anything at all." lege subsidize the student's charges. -

How the Atlanta Daily World Covered the Struggle for African American Rights from 1945 to 1985

Abstract Title of Dissertation: THE CAUTIOUS CRUSADER: HOW THE ATLANTA DAILY WORLD COVERED THE STRUGGLE FOR AFRICAN AMERICAN RIGHTS FROM 1945 TO 1985 Name: Maria E. Odum-Hinmon Doctor of Philosophy, 2005 Dissertation Directed By: Prof. Maurine Beasley, Ph. D. Philip Merrill College of Journalism This dissertation is a study of the Atlanta Daily World, a conservative black newspaper founded in 1928, that covered the civil rights struggle in ways that reflected its orientation to both democratic principles and practical business concerns. The World became the most successful black daily newspaper in the nation after becoming a daily in 1932 and maintaining that status for nearly four decades. This dissertation details how this newspaper chronicled the simultaneous push for civil rights, better conditions in the black community, and recognition of black achievement during the volatile period of social change following World War II. Using descriptive, thematic analysis and in-depth interviews, this dissertation explores the question: How did the Atlanta Daily World crusade for the rights of African Americans against a backdrop of changing times, particularly during the crucial forty- year period between 1945 and 1985? The study contends that the newspaper carried out its crusade by highlighting information and events important to the black community from the perspective of the newspaper’s strong-willed publisher, C. A. Scott, and it succeeded by relying on Scott family members and employees who worked long hours for low wages. The study shows that the World fought against lynching and pushed for voting rights in the 1940s and 1950s. The newspaper eschewed sit-in demonstrations to force eateries to desegregate in the 1960s because they seemed dangerous and counterproductive when the college students wound up in jail rather than in school. -

Live-In Lover Complaints: Think Twice Before You File How Does Your Firm Face Risk?

2FWREHU9ROXPH1XPEHU Live-In Lover Complaints: Think Twice Before You File How does your firm face risk? Claims against attorneys are reaching new heights. Are you on solid ground with a professional liability policy that covers your unique needs? Choose what’s best for you and your entire firm while gaining more control over risk. LawyerCare® provides: Company-paid claims expenses—granting your firm up to $5,000/$25,000 outside policy limits Grievance coverage—providing you with immediate assistance of $15,000/$30,000 in addition to policy limits Individual “tail” coverage—giving you the option to cover this risk with additional limits of liability PracticeGuard® disability coverage—helping your firm continue in the event a member becomes disabled Risk management hotline—providing you with immediate information at no additional charge It’s only fair your insurer provides you with protection you can trust. Make your move for firm footing and call today. Rated A+ (Superior) by A.M. Best Professional Liability Coverage LawyerCare.com • 800.292.1036 for Georgia Lawyers & Firms T urn to smarter tools for legal research. Visualize search results to see the best results Only Fastcase features an interactive map of search results, so you can see the most important cases at a glance. Long lists of text search results (even when sorted well), only show one ranking at a time. Sorting the most relevant case to the top might sort the most cited case to the bottom. Sorting the most cited case to the top might sort the ® most recent case to the bottom. Fastcase’s patent-pending Interactive Timeline view shows all of the search results on a single map, illustrating how the results occur over time, how relevant each case is Smarter by association.based on your search terms, how many Log in at www.gabar.org times each case has been “cited generally” by all other cases, and how many times each case has been cited only by the super-relevant cases within the search result (“cited within” search results). -

Turning the Tide in the Civil Rights Revolution: Elbert Tuttle and the Desegregation of the University of Georgia

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 5 1999 Turning the Tide in the Civil Rights Revolution: Elbert Tuttle and the Desegregation of the University of Georgia Anne S. Emanuel Georgia State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legal Biography Commons Recommended Citation Anne S. Emanuel, Turning the Tide in the Civil Rights Revolution: Elbert Tuttle and the Desegregation of the University of Georgia, 5 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (1999). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol5/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TURNING THE TIDE IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION: ELBERT TUTTLE AND THE DESEGREGATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA Anne S. Emanuel* Truth is sometimes stranger than fiction. So it was in 1960 when Elbert Tuttle became the Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the federal appellate court with jurisdiction over most of the Deep South. Part of the genius of the Republic lies in the carefully calibrated structure of the federal courts of appeal. One assumption underlying the structure is that judges from a particular state might bear an allegiance to the interests of that state, which would be reflected in their opinions. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Howard Moore, Jr

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Howard Moore, Jr. Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Moore, Howard, 1932- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Howard Moore, Jr., Dates: April 14, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 9 Betacame SP videocasettes (4:12:17). Description: Abstract: Civil rights lawyer Howard Moore, Jr. (1932 - ) played a major role with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in the Supreme Court cases of Georgia v. Peacock and Georgia v. Rachel. Moore represented Julian Bond in his successful fight to take his seat in the Georgia House of Representatives, and become a part of the Angela Davis defense team. Moore was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on April 14, 2007, in Berkeley, California. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_137 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Attorney Howard Moore, Jr. was born on February 28, 1932 in Atlanta, Georgia to Bessie Sims Moore and Howard Moore, Sr. Growing up on Fort Street, his paper route sent him down Auburn Avenue where he encountered many of Atlanta’s prominent citizens, including Colonel Austin T. Walden, the dean of the black lawyers. When his mother left to work at a Lorain, Ohio steel plant, Moore lived with his aunt. He attended David T. Howard School, graduating in 1950. Attending Morehouse College, Moore wanted to be a journalist like Atlanta Daily World’s Lerone Bennett but was drawn to political science where he was taught by Dr. -

Social Justice Advocacy in Action: Finding Your Passion

SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY IN ACTION: FINDING YOUR PASSION June 7, 2019 ICLE: Annual Meeting Series Friday, June 7, 2019 SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCACY IN ACTION FINDING YOUR PASSION Copyright © 2019 by the Institute of Continuing Legal Education of the State Bar of Georgia. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ICLE. The Institute of Continuing Legal Education’s publications are intended to provide current and accurate information on designated subject matter. They are off ered as an aid to practicing attorneys to help them maintain professional competence with the understanding that the publisher is not rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. Attorneys should not rely solely on ICLE publications. Attorneys should research original and current sources of authority and take any other measures that are necessary and appropriate to ensure that they are in compliance with the pertinent rules of professional conduct for their jurisdiction. ICLE gratefully acknowledges the eff orts of the faculty in the preparation of this publication and the presentation of information on their designated subjects at the seminar. The opinions expressed by the faculty in their papers and presentations are their own and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the Institute of Continuing Legal Education, its offi cers, or employees. The faculty is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

the niversi Bulletin MARCH, 1974 Commencement 255 Degrees Awarded 3 Charter Day Audience Hears Atlanta School Superintendent 6 Westerfield Conference 10 School of Education Offers New Training in Special Education 12 Exhibition of Afro-American Art Begins Tour in Atlanta 14 Campus Briefs 15 Faculty Items 25 Alumni News 27 Cover: “Yield Not” by Benjamin Britt, one of more than sixty pieces of art from the exhibition “Highlights from the SECOND CLASS POSTAGE Atlanta University Collection of Afro-American Art." PAID AT ATLANTA, GEORGIA The exhibition opened at Atlanta's High Museum in November and will travel to ten other cities over the next two years. 255 Graduated at Summer Commencement Exercises Christopher edley. execu¬ tive Director of the United Negro College Fund, delivered the principal address at Summer Commencement Exercises on Friday, August 3. Mr. Edley, formerly officer in charge of law programs at the Ford Foundation, joined the UNCF April 1, 1973. He is a graduate of Howard University and received his law degree at Harvard University. Mr. Edley was an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia for three years and has also held posts with the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights and the Federal Housing and Home Finance Agency. Two hundred fifty-five degrees were awarded, including eight Specialists in Education, two Specialists in Library Service, and one Ph.D. in Guidance and Counseling. The School of Arts and Sciences awarded 27 Master of Arts degrees and 9 Master of Science degrees; the School of Library Service awarded 58 master's degrees; the School of Education. 146; and the School of Business Administration, 5. -

LOTTIE H. WATKINS by K. Nasstrom Interview 6/25/92 Page 1 GEORGIA

LOTTIE H. WATKINS by K. Nasstrom Interview 6/25/92 Page 1 GEORGIA GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTATION PROJECT ATLANTA WOMEN IN PUBLIC LIFE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY AND SOUTHERN ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL NARRATOR: LOTTIE HEYWOOD WATKINS INTERVIEWER: KATHRYN L. NASSTROM DATE: JUNE 25, 1992 NASSTROM: This is Kathy Nasstrom interviewing Lottie Watkins for the Southern Oral History Program and the Georgia Government Documentation Project on June 25, 1992. I would like to start with some biographical'information. You are an Atlanta native; is that right? WATKINS: Yes. NASSTROM: You were born and raised here? WATKINS: Yes. NASSTROM: And what year were you born? WATKINS: 1919. NASSTROM: And what part of the city were you born in? WATKINS: I was born in the city of Atlanta. NASSTROM: In what part of the city? WATKINS: You call it the "West Side" of Atlanta. NASSTROM: And were your parents both natives of Atlanta, or did they move to this area? Interview number G-0088 in the Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) at The Southern Historical Collection, The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. WATKINS/Nasstrom Interview 6/25/92 Page 2 WATKINS: My mother was a native Atlantan, my father was born in Sumter, South Carolina. NASSTROM: And when did that relocation to Atlanta take place for him? WATKINS: Well, I can't answer that. I really don't know. NASSTROM: You don't recall that? WATKINS: No, I never heard him say. NASSTROM: Okay, when you were growing up, do you remember learning very much about your parents' background? WATKINS: There were five of us.